Yasukuni Shrine

Imperial Shrine of Yasukuni

The Imperial Shrine of Yasukuni

is a Shintō shrine north of the Imperial Palace

complex in Tōkyō, just north of the

Budokan arena and near a station on the Toei Shinjuku

subway line.

It commemorates people who died in the service of the

Empire of Japan, an entity that existed from the

Meiji Restoration of 1869 to the end of

World War II.

It lists or "enshrines" some 2,466,532 creatures,

largely men in war service (willingly or not) but also

women, children, and some military service animals and pets.

This includes some 1,068 war criminals, 14 of them considered

to be Class A war criminals and executed after the end of

World War II for their roles in planning and leading the war.

I thought I wanted to visit while first planning my trip.

Then I decided I didn't want to.

Then I changed my mind again, and went.

I'm glad I did.

Shintō and Buddhism in Japan

The shrine was established to honor those who died for

the Emperor at the Meiji Restoration,

the 1869 restoration of power

to the Emperor over the Shōgunate.

It was later expanded to include all those who died in the

service of the Empire.

The associated Chinreisha Shrine within the complex

was built to enshrine the souls of all

people of all nationalities who died during World War II.

Shintō

is a uniquely Japanese spiritual tradition.

See my pages on

Buddhism and Shintō in Japan

to make sense of what follows, especially the enshrining

of kami or spirits in Shintō shrines.

The Yasukuni Shrine was established in 1869, based on an earlier shrine in Kyōto and caught up in the significant events of 1868-1869.

In December of 1862 by the Western calendar the Shinsōsai ritual was held at the Shindō Sōsaijō Reimeisha, currently known as the Ryozen Gokoku Shrine at Higashiyama in Kyōto. Three Saijin or deities were enshrined there, including the kami or spirits known as Kukurihime no Kami.

Imperial Names —

The reigning Emperor is always called simply "The Emperor".

The confusing thing is that they are given a personal name

at birth, by which they may be known as long as they live,

but after their death they are known by a posthumous name

referring to their era.

The Emperor in the late 1860s had the personal name of

Matsuhito but his reign was the

Meiji period and he is now known as

Emperor Meiji.

Similarly, the Emperor who reigned through much of the

20th century was named Hirohito.

Now he and the period 1926-1989 are known as

Shōwa.

The Meiji Restoration returned power to the Emperor of Japan, after the Shōgunate had held power since 1603 CE.

The American Naval commander Commodore Matthew Perry had led the "Black Ships" to Edo (soon to become Tōkyō) harbor in 1853, forcing Japan to open its ports to foreign ships. The Shōgunate had failed to prevent this, confidence was lost, and the Shōgun was on the way out.

Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the 15th Tokugawa Shōgun, "put his prerogatives at the Emperor's disposal" on 9 November 1867 by the Western Gregorian Calendar, and resigned ten days later.

The Boshin War or Boshin Sensō, also known as the Japanese Revolution, was the civil war fought from 1868 to 1869 in which forces of the Tokugawa shōgunate were defeated and the Imperial Court regained political power.

In May of 1868 the Dajokan Fukoku or Proclamation by the Grand Council of State ordered that the warriors who died while fighting for the Emperor be enshrined at Kyōto.

By the July of 1869 the Emperor's forces controlled most of the Japanese archipelago. The Emperor donated an estate in the port city which had been known up to that time as Edo, lately a stronghold of the Tokugawa Shōgunate. The city had become one of the largest cities in the world. The estate was to become the Imperial Shrine of Yasukuni. The Emperor chose the name Yasukuni. It comes from a classical-era Chinese text and means "Pacifying the Nation".

Amazon

ASIN: B0000062FR

Amazon

ASIN: B0015RCUSC

The estate where the shrine was to be established was on the north side of the Imperial Palace grounds. Now it's just north of the Budokan arena.

In late July of 1869 the first Gōshisai or festival for enshrining the war dead was held at the new shrine. The dead enshrined at Kyōto were transferred there, and 3,588 new war dead were enshrined.

The Southwestern War or Seinan Sensō of 1877 started as a revolt by samurai opposed to the newly restored Imperial government. It is often called the Satsuma Rebellion in English, but it was on the scale and impact of a full civil war rather than a localized uprising. The Southwestern War was the conclusion of a series of armed uprisings by the samurai class supporting the Shōgunate against the Imperial Court. It took place in Kyūshū, the furthest southwest of the four main islands.

The samurai class saw that modernization was ending their high social status and hurting them financially. They took military action against the Emperor's forces in an attempt to re-establish Shōgunate power. This was the last meaningful rebellion against Imperial power.

Things had modernized since the glory days of the samurai class. Imperial troops used howitzers and observation balloons. The samurai rebels used western tactics, guns, and cannons. But they ran out of ammunition and had to fall back to close-quarter battle with swords and bows and arrows.

The Imperial forces won. The rebellion was effectively the end of the samurai class. Its leader, Saigō Takamori, committed seppuku when the rebellion failed. Emperor Meiji pardoned Saigō posthumously in February 1889. A statue of Saigō Takamori, considered the last true samurai, now stands in Ueno Kōen or Ueno Park in Tōkyō

Statue of Saigō Takamori and his dog in Ueno Park in Tōkyō.

In 1887 the military took control of enshrining war dead at Yasukuni. The Empire expanded with the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, and Okinawans, Ainu, and Koreans were enshrined at Yasukuni alongside the ethnic Japanese. But not Taiwanese, as there had been organized resistance after the Japanese invasion of Taiwan in 1895. That policy changed during World War II when Taiwanese were forcibly conscripted into the Japanese military.

Other major "opportunities for enshrinement" came with the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), Japan's involvement in the Asian and Pacific theatres of World War I (1914-1918), the Siberian Intervention after the start of the Russian Revolution (1918-1922), and Japan's Invasion of Manchuria (1931-1932).

| Conflict | Years | Enshrined | |

|

Boshin War and Meiji Restoration |

Civil War | 1867-1869 | 7,751 |

| Invasion of Taiwan | Punitive expedition against the Palwan, Taiwanese aboriginal people | 1874 | 1,130 |

| Ganghwa Island Incident | Conflict with Joseon Army | 1875 | 2 |

|

Southwestern War or Seinan Sensō |

Civil War | 1877 | 6,971 |

| Imo Incident | Conflict with Joseon Rebel Army in Korea | 1882 | 14 |

| Gapsin Coup | Failed coup in late Joseon Dynasty in Korea | 1884 | 6 |

| First Sino-Japanese War | War with Qing Dynasty China over Korea | 1894-1895 | 13,619 |

| Boxer Uprising | Eight-Nation Alliance invades China | 1901 | 1,256 |

| Russo-Japanese War | War with Russian Empire over control of Korea and Manchuria | 1904-1905 | 88,429 |

| World War I and Siberian Intervention | Conflict with Central Powers over German holdings in East Asia and Pacific (1914-1918), and Allied intervention in the Russian Revolution (1918-1922) | 1914-1918 | 4,850 |

| Battle of Qingshanli | Conflict with Korean Independence Army in Manchuria | 1920 | 11 |

| Jinan Incident | Conflict with Kuomintang Chinese forces over Jinan, in Shandong, China | 1928 | 185 |

| Wushe Incident | Major uprising against Japanese colonial forces in Taiwan | 1930 | uncertain |

| Nakamura Incident | Extrajudicial killing of Japanese military personnel in Manchuria | 1931 | 19 |

| Mukden Incident | Staged event carried out by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the following Japanese invasion of Manchuria | 1931-1937 | 17,176 |

| Second Sino-Japanese War | Invasion of China leading into World War II | 1937-1941 | 191,250 |

| World War II and Indochina War | Conflict with Allied nations in Pacific Theatre of World War II, and with French and French-allied forces in Indochina | 1941-1945 | 2,133,915 |

World War II dominates numerically, but there are over 330,000 dead from sixteen other conflicts or incidents.

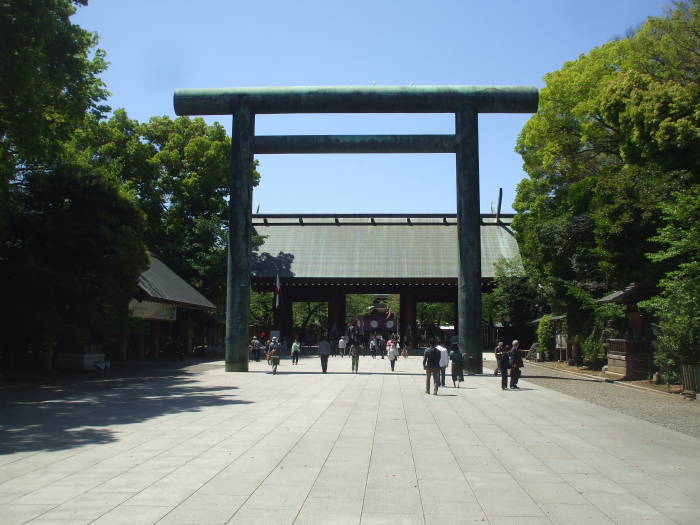

Daiichi Torii

The enormous Daiichi Torii or Ōtorii is the outermost torii you pass through as you enter the shrine precincts.

Torii symbolize a passage into increasingly sacred space. The steel Daiichi Torii at Yasukuni was the largest torii in Japan when it was first erected in 1921. It is approximately 25 meters tall and 34 meters wide.

The original was removed in 1943 "due to weather damage" and the current version was erected in 1974.

Amazon

ASIN: 0760341222

Amazon

ASIN: 1568331495

Yes, yes, you're saying "Weather damage, U.S. fire-bombing raids, whatever", and that's definitely a factor. However... Both Shintō shrines and Buddhist temples demonstrate the transience of all existence. Pagodas are Buddhist temples traditionally built in the form of all all-wooden towers topped with metal spires, and the most auspicious locations are at high elevations, as at Kōya-san.

Don't credit solely to massive U.S. incendiary bombing raids what can also be explained by religious site selection and design uninformed by modern theories of lightning suppression and fire prevention.

Ōmura Masujirō

Anyway, you pass through the outermost torii and past the statue of Ōmura Masujirō. He was known as "The Father of the Modern Japanese Army". This bronze statue, created in 1893, is Japan's first western-style commemorative bronze statue.

Ōmura Masujirō was the son of a rural physician. He studied medicine in Osaka, and then in Nagasaki under the German physician Philipp Franz von Siebold. Nagasaki was the only port open to foreigners, and von Siebold was the first European to teach western medicine in Japan.

Ōmura returned to his village to practice medicine. But he then accepted an offer to serve as an expert in Western studies and teach at a military school, in exchange for the samurai rank that he was not born into.

He returned to Nagasaki to study warship construction and navigation. Then he traveled to Edo in 1856, appointed as an instructor at the shōgunate's institute for western studies. He learned English under the Yokonaha-based American missionary James Hepburn, who had devised an influential system of transliterating Japanese into the Latin alphabet.

Ōmura was appointed hyōbu daiyu under the new Meiji government, equivalent to Vice Minister of War. He was tasked with establishing a national army along western lines, and he modeled it largely on the French system.

Daini Torii

The Daini Torii or Seidō Ōtorii is the second torii.

This is the largest bronze torii in Japan. It was erected in 1887 to replace a wooden second torii.

Just beyond it to the left is a shelter with the water fountain and reservoir for the ceremonial purification rite.

Shintō refers to the purification rite as temizu, the water-filled reservoir as mizuya or chōzubachi, and the small shelter or pavilion as the chōzuya or temizuya.

Buddhism calls the shelter or pavilion a chozu-yakata. The basin itself is the tsukubai, a word based on the verb tsukubau meaning "to bow down", to humble yourself.

Yasukuni is a Shintō shrine, so the Shintō terms apply. The Ōtemizusha or large temizuya was built in 1940.

The Shinmon is a 6-meter-tall cypress gate. It was first built in 1934, then "restored" (meaning almost if not entirely replaced) in 1994.

The 1.5-meter chrysanthemum crests are the symbol of the Emperor of Japan. Their presence on the doors of the Shinmon is significant. This is an Imperial shrine, part of the state in a way.

Once through the Shinmon you approach the Chumon Torii, a cypress torii that is the third and last torii before reaching the haiden.

The haiden is the main prayer hall. It was built in 1901, with the roof renovated in 1989. Beyond the haiden, much is off-limits to the public.

The honden (or shinden or shōden) is the most sacred structure at a Shintō shrine. It is the main shrine where, as Shintō puts it, the enshrined deities reside. The Yasukuni honden was built in 1872 and refurbished in 1889. It's generally closed to the public, and it is where the priests perform the Shintō rituals.

Beyond that is the Reijibo Hōanden or the Repository for the Symbolic Registers of Divinities, where a handmade paper document lists the names of all the kami or divinities enshrined and worshiped at Yasukuni.

Shintō Meets Roman Catholicism, and World War II

In 1932, two students of Sophia University or Jōchi Daigaku, a private Jesuit research university in Tōkyō, refused to join a school-sponsored visit to Yasukuni Shrine. They said that, as Roman Catholics, a visit to a Shintō shrine conflicted with their religious beliefs.

In 1936 the Propaganda Fide or the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, part of the Roman Curia, issued the Instruction Pluries Instanterque approving visits to Yasukuni Shrine as a non-religious expression of patriotism.

As the 1930s progressed, Japan's government became more militaristic. It extended military activity throughout Asia and the western Pacific Ocean. It also increased its control over the memorialization of war dead.

As the tensions of the late 1920s lead into the invasion of Manchuria in 1931-1932, and then to the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1941, the Yasukuni Shrine played a key role in military and civilian morale. Enshrinement at Yasukuni gave meaning and nobility to those who died for Japan. Pilots leaving for suicidal Kamikaze missions during the Pacific War told each other that they would "meet again at Yasukuni."

Post-War Yasukuni

After the end of World War II, the U.S.-dominated Occupation forces decreed that State Shintō had to end.

The U.S. used the term "State Shintō" during World War II and the Occupation. It never was a Japanese term. The U.S. used it to describe the ideological use of Shintō on a national scale. Shintō as controlled by the Imperial government held that any wars waged for the Emperor were just, and anyone who died fighting for the Emperor was an eirei or hero spirit.

The U.S.-led Occupation Authorities or GHQ initially planned to burn down the Yasukuni Shrine complex and build a dog-racing track there. However, Father Bruno Bitter of the Roman Curia and Father Patrick Byrne of Maryknoll University stridently opposed this plan.

GHQ let the Yasukuni Shrine stand, but they insisted that it had to conform to the separation of church and state: Yasukuni Shrine must become either an entirely secular government institution, or a religious institution completely separate from the national government.

The Yasukuni Imperial Shrine chose to become a religious corporation independent of the national Association of Shintō Shrines.

The Roman Curia went on to reaffirm the Instruction Pluries Instanterque.

The Controversies

War criminals who had been prosecuted by the International Tribunal for the Far East were excluded from enshrinement at Yasukuni. At least at first...

In 1951, after the Treaty of San Francisco was signed, government authorities began considering the enshrinement of the Class B and Class C war criminals, along with giving veterans' benefits to their survivors.

Between 1959 and 1967 the 1,054 Class B and Class C war criminals, those convicted of war crimes but who hadn't been involved in the planning, preparation, or waging of the war, were enshrined at Yasukuni. Often this took place against the wishes of their surviving relatives.

The fourteen Class A war criminals, the prime ministers and top generals, were presented by the government to the shrine in 1966. The shrine passed a resolution in 1970 to also enshrine them. The scheduling of the enshrinement was left to the chief priest, who delayed it until he died in 1978. His successor, Nagayoshi Matsudaira, rejected the verdicts of the Tokyo war crimes tribunals. He enshrined the Class A war criminals in a secret ceremony on 17 October 1978.

Emperor Hirohito (as he was known at the time, now the Shōwa Emperor) was upset with this. His visit to the shrine in 1975 was his last. He never returned to Yasukuni after the Class A war criminals were enshrined. His successor Akihito, the Heisei Emperor, has never visited.

The head priest at the Honzen-ji Temple asked Pope Paul VI to say a mass for the repose of the 1,618 men condemned as Class A, B, and C war criminals. Paul VI (who reigned 1963-1978) promised to do that, but never got around to it before dying. Two Popes later, John Paul II did that in 1980, holding a mass in Saint Peter's Basilica for the 1,618 Japanese war criminals.

In 2005 the shrine added a monument to Justice Radha Binod Pal, the Indian judge who was the only member of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East to find all Japanese defendents not guilty of war crimes.

The 14 Class A war criminals include:

7 who were executed by hanging:

Hideki Tōjō,

Seishirō Itagaki,

Heitarō Kimura,

Kenji Doihara,

Akira Mutō,

Kōki Hirota, and

Iwane Matsui;

4 imprisoned for life:

Yoshijirō Umezu,

Kuniaki Koiso,

Hiranuma Kiichrō, and

Toshio Shiratori;

1 imprisoned for 20 years: Shigenori Tōgō;

and two died from illness before sentencing was decided:

Osami Nagano and Yosuke Matsuoka.

All of the imprisoned had their sentences commuted or were released by 1958.

Amazon

ASIN: 0465068367

Amazon

ASIN: 0060933879

Amazon

ASIN: 038549565X

Amazon

ASIN: 1510702261

The Controversies Continue

Various Prime Ministers of Japan have visited Yasukuni over the past few decades, using varying levels of Plausible Deniability. Arrive in non-offical vehicles, sign their name but no job title in the register, that sort of thing.

Korean, Chinese, and other national governments express varying levels of outrage. The shrine also figures prominently in domestic politics. Every year there is speculation as to whether the Prime Minister will "unofficially visit" the shrine on August 15th, the anniversary of the end of World War II. There is an ongoing debate over the role of religion in the Japanese government. An organization the Yasukuni Shrine sees as its lay organization serves as a strong link to the LDP, the governing Liberal Democratic Party.

And see here the people "baptized" as Mormons after their deaths.

The Yasukuni Shrine will "enshrine" individuals without consulting, and against the wishes of, surviving family members. Families from South Korea have asked that the shrine remove their relatives from the Shrine's lists. But the Yasukuni priesthood says that once a kami has been enshrined, it is "merged" with the other kami occupying the same seat, and therefore it cannot be separated and removed from the list.

There is now a museum at the Yasukuni Shrine where they glorify the Kamikaze pilots and explain how the U.S. is to blame for World War II. That's much like how the Neo-Confederates in the U.S. claim that the U.S. Civil War had nothing to do with slavery and was actually a "War of Northern Aggression."

I didn't bother visiting the museum, as I didn't want to pay for a ticket that would be used to perpetuate the nonsense.

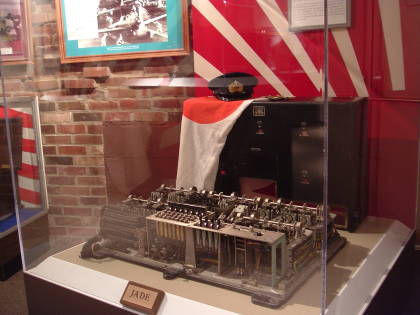

Speaking of which, here is a rare flag of Imperial Japan:

During a month in Japan, I saw the flag of Imperial Japan four times: three at the large Okunoin cemetery at Kōya-san and this one at Yasukuni Shrine. How horrible was that for me as a visitor from America? Not very, as I'm sorry to say that things are far worse in my home country.

Meanwhile, in America

I was in Japan a few months after the inauguration of a U.S. President who was elected with the enthusiastic support of the Ku Klux Klan and several other White Supremicist and neo-Nazi groups.

In the neo-Confederate swamp of Indiana, where I live, in any typical day you see more than four examples of the Confederate Flag, the symbol of treason, racism, and failure.

The small town in Indiana where I grew up is now the home of two neo-Nazi organizations openly operating on a national scale.

The Neo-Confederates claim that they are just honoring military sacrifice. Let's see if their claim makes any sense.

Just in the 19th century, in addition to the Civil War, the U.S. was involved in several major international conflicts including the First Barbary War (1801-1805), the War of 1812 (1812-1815), the Second Barbary War (1815), the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), the Second Opium War (1856-1860), the Spanish-American War (1898), the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), and the Moro Rebellion (1899-1913).

In addition, the U.S. undertook several international punitive expeditions and minor conflicts throughout the 19th century, including the Aegean Sea anti-piracy operations (1825-1828), the First and Second Sumatran Expeditions (1832 and 1838), the Ivory Coast Expedition (1842), the Johanna Expedition (1851), the First and Second Fiji Expeditions (1855 and 1859), the Shimonoseki Campaign (1863-1864), the Formosa Expedition (1867), the U.S. Expedition to Korea (1871), the Second Samoan Civil War (1898-1899), plus even smaller border conflicts with Mexico, and a large number of armed conflicts against Native American tribes, all of which would seem to align with the white supremacist goals of the Neo-Confederates.

But the only military action the Neo-Confederates care about is their failed struggle to preserve slavery and white supremacy.

Then, three months after I returned from this trip, a large Virginia rally by white supremacist, neo-Confederate, and neo-Nazi organizations turned violent. They killed one woman and injured 19 other people, five of them critically. After three days of criticism and pressure from political figures and the public, the U.S. President finally issued a grudging criticism of the K.K.K., neo-Nazis, and other white supremacists. Then, the following day, he went back to his original statement that the neo-Nazis and the Klan shouldn't be blamed and that their membership included "some very fine people".

Yes, Japan has some "history" textbooks and the "museum" at the Imperial Yasukuni Shrine that deny what really happened during World War II and the years leading up to it. They're very much like the "history" textbooks used in several states in the U.S. to teach children that the American Civil War had nothing to do with slavery or racism. See The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and NPR about Virginia school textbooks, and The Washington Post, The New York Times, and the Houston Chronicle about Texas school textbooks, both of those among many others.

So, are there delusional people with offensive beliefs in Japan? Yes, a few, but they're not nearly as common or as dangerous as in the U.S.

Other topics in Japan: