The Painted Churches of Bucovina and Gura Humorului

Moldova, Bucovina, and the Painted Churches

Athens to Parisby Train

We are in northeastern Romania, in an area known as Bocuvina and within the region of Moldova, visiting the beautiful painted churches at the monasteries. We have just arrived on a train from Bucharest through Suceava to Gura Humorului. This is part of the Athens to Paris by Train series, start at the beginning to get the background and the details so far.

This area is known as Moldova or Moldavia. The history goes way back and today's national borders are not always closely tied to divisions of language and culture. Adding to the confusion, there is a country of Moldavia, formerly a republic of the Soviet Union but now an independent nation. What we now call the country of Moldavia makes up some, maybe half, of the region of Moldavia. But not all of the country of Moldavia identifies itself with the cultural region of Moldavia. The strip of the country of Moldavia east of the Dniester River and along the Ukrainian border claims to be an independent Slavic nation, to the point of establishing a somewhat autonomous region that styles itself as the independent Republic of Trans-Dniestria. Russia encourages this further confusion, but hardly anyone else recognizes Transdneistria as an actual country.

For purely political purposes, the Soviets insisted that while the language spoken in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was related to that spoken in Romania, they were two distinct languages. The reality is that Moldavian is a dialect of Romanian, or even closer related and not really different enough to appropriately be called a dialect, simply Romanian with slightly different pronunciation of some words and a different set of loan words from neighboring countries.

So there is a cultural region overlapping two countries, and an independent nation. Which of them is Moldova and which is Moldavia? It depends on who you ask! Romanians say that the culture and region is Moldova while the neighboring country is Moldavia, but the people in that country say that it is the other way around.

It gets even more confusing. There is also a region known as Bucovina. Well, at least it's spelled that way by Romanians, you also see Bukovina, Bukovyna, Bukowina, and Буковина. Bucovina overlaps the border region between northeastern Romania and southwestern Ukraine.

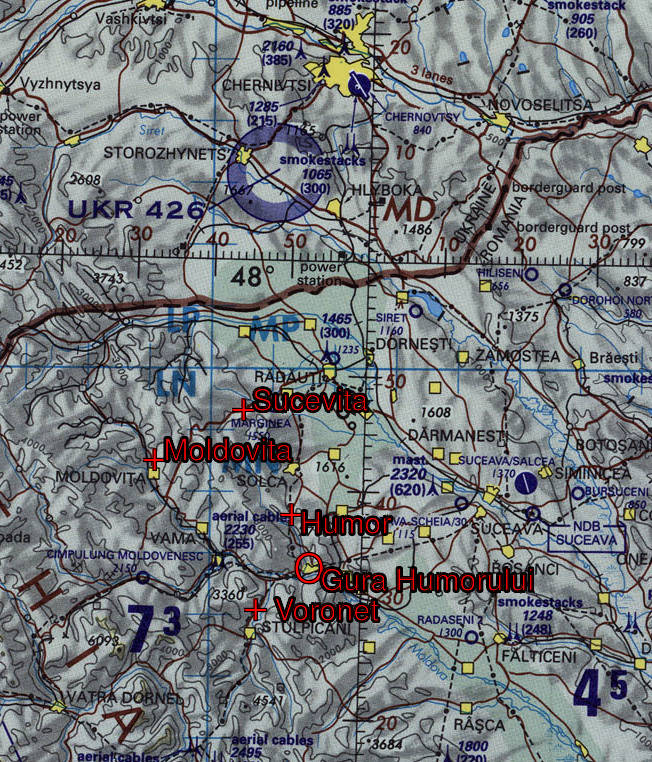

The simple map above shows Bucovina's approximate location across the Romanian-Ukrainian border with a large red circle. This is the area we have come to see.

This more detailed map shows central Bucovina. The top third or so of the map shows part of Ukraine, the rest shows part of northern Romania. The town of Gura Humorului is circled, and four of the nearby prominent monasteries are indicated by red crosses.

As described within the Athens to Paris by Train series of pages, we arrived here by train from Bucharest. This involved a train from Bucharest to Suceava, shown toward the right edge of the detailed map, then a wait of about 90 minutes for a local train to Gura Humorului.

We stayed in Gura Humorului while exploring the nearby area of Bucovina and visiting the monasteries of Voroneţ, Moldoviţa, Suceviţa, and Humor.

The Romanian letter Ţ/ţ is pronounced as an English speaker would pronounce the "ts" in "cats". Humor is pronounced as who-more and not like the English word pronounced as hue-more.

Romanian Orthodox Christianity and its Iconography and Architecture

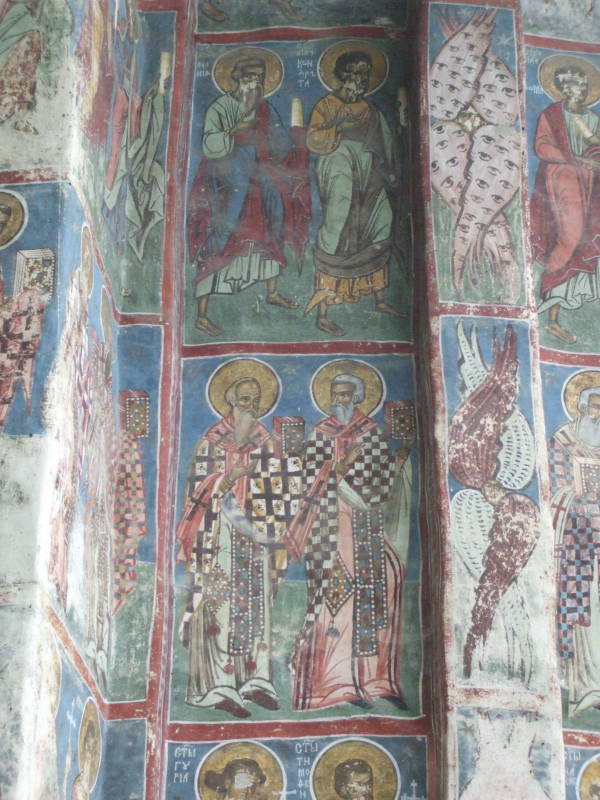

Above we see Григорїе Митрополи (or Grigoriye Mitropoli) at left, and a saint, Сты Диїнль, Saint Daniel, at right. Сты is short for Сваты, Svati or "Saint" (or literally "Holy"). Daniel is holding an excerpt from Psalm 33: "Come, my sons, listen to me, I will teach you to fear God."

Daniel the Hermit was the first abbot of a skete or monastic community at Voroneţ before the present monastery was built. The Voivode Stefan was traveling from Neamt Fortress to the highlands of Moldavia, and stopped here to visit Daniel. Daniel heard the ruler's confession. Then Stefan asked, as he felt was unable to continue fighting against the Turks, should he surrender the country?

Daniel told Stefan not to surrender, as he was to win the war. But after his victory, Stefan must build a monastery here under the patronage of Saint George.

An inscription carved in stone above the entrance door to the narthex says:

I, Voivode Stefen, by the Grace of God Ruler of Moldavia, son of Bogdan, have started to have the monastery of Voroneţ built to the glory of the holy and well-known Saint George, the great and victorious martyr, in 6996 in May on the 26th, on one day of Monday after the Pentecost, and I had it finished the same year, in September 1488.

The monastery was built between May and September of one year. The year is referenced in two ways — 6996 years since the creation of the Earth (on September 1, 5509, in Byzantine reckoning), and 1488 C.E.

This painting was done in 1547, when Grigoriye Roşca, the Metropolitan Bishop of Moldavia (or Grigoriye Mitropoli), added an exonarthex onto the western or entry end of the church.

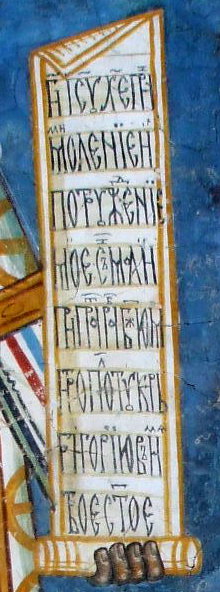

Here is a better view of the scroll held by Grigoriye Mitropoli. The Cyrillic script of that era is used everywhere to to write a mixture of Church Slavonic, a Slavic language, and the Latin-based Romanian of the era. So it's challenging to figure out just precisely what you're looking at some of the time.

| Historic Cyrillic letters used in Church Slavonic and Romanian before the 1860s | |

| Ѡ | Omega — Replaced by О/о in modern Russian. |

| Ѣ | Yat — Replaced by Е/е in modern Russian. |

| Ѧ | Little Yus — Nasalized front vowel. The nasalized vowels have disappeared from modern Slavic languages using the Cyrillic alphabet, although it survives in Polish as Ę/ę. Ѧ was used in Russian to represent Я/я in the middle or end of words until the Russian typographical reform of 1708. |

| Ѩ | Iotified Little Yus — Like Ѩ but preceded by a sound similar to Y in English "yes". Ѧ was pronounced like a nasal я while ѩ was pronounced like a nasal иа. |

| Ѫ | Big Yus — Nasalized back vowel. This letter remained in the Bulgarian alphabet until the arrival of the Soviets and communism in 1945, although by that time the former back nasal vowel in Bulgarian had changed to be pronounced the same as Ъ/ъ. Romanian used this where today you would find ы. |

| Ѭ | Iotified Big Yus — Like Ѫ but preceded by a sound similar to Y in English "yes". |

| Ѯ | Ksi — Pronounced like Cyrillic кс or Latin ks, mainly used in ecclesiastical Greek loan words. |

| Ѱ | Psi — replaced by the phonetically equivalent digraph пс. |

| Ѳ | Fita — Pronounced like Cyrillic Ф/ф, so the Greek based name Θεόδωρος or "Theodoros" became Russian Фёдор or "Fyodor". |

| Ѵ | Izhitsa — Came from the Greek Υ/υ and used in Greek words and names such as Сѵрилъ or "Cyril". |

| Ѹ | Uk — An archaic form of У/у. |

Even if you can deal with the eminently logical modern Cyrillic alphabet, the older script used with Church Slavonic is filled with some archaic letters and some easily overlooked ligatures.

However, as we see below when we start visiting the monasteries, there is a very, well, orthodox organization to the design of a monastery church and its frescos and other decorations.

So, once you figure out the usual organization and iconography, you know what to look for and you know what you're seeing without much need to decipher a mixture of Church Slavonic script and medieval ecclesiastical Romanian. It's not so much "What did they depict here?" as "How did they depict it this time?"

The churches are aligned from west to east. You enter at the west end, the altar is at the far east end.

You enter through a porch which may be open or enclosed. At Voroneţ the porch has a solid west wall covered with a Last Judgement painting, as seen below. You enter the porch from arched doorways at either side. In other churches the porch is open with arches or at least doorways on its west side and at its north and south ends.

The doorway from the porch leads into the church, into the pronaos or narthex This chamber is the connection between the outside world and the church. In the past only confirmed Orthodox worshippers could continue further into the church, although this tradition has largely ended. The outermost chamber is typically decorated with a gruesome array of martyrdoms in process.

From the pronaos a second door leads further into the church. In larger churches there is a second similar chamber where tombs of the founder or early leaders may be found. In simpler designs those tombs would be out in the pronaos. If there is a tomb room, it possibly has a treasury either concealed below ground level or on an upper level.

The naos or nave is the main room for the celebration of the liturgy, where the people would stand during a service. There are no pews or other seats in an Orthodox church. Traditional Orthodox churches follow the Jewish practice with men standing to the right and women standing to the left.

The dome above the naos represents the sky or the dome of heaven. In these painted churches there is a tower, sometimes octagonal in cross-section rather than cylindrical, extending above the main dome of the naos. The dome within that tower with a Christ Pantocrator painting, fresco, or mosaic. Hanging directly below that tower opening is the horos, a circular chandelier with depictions of the saints and apostles.

The nave or naos is roughly square with three semicircular apses, the overall shape referencing the cross. The apse at the front is beyond the iconostasis and as the innermost sanctuary contains the altar.

Voroneţ Monastery

Remember that in Romanian the letter "ţ" is pronounced like the "ts" in the English word "cats", so to an English speaker "Voroneţ" is pronounced as if it was spelled "Voronets".

We had arrived in Gura Humorului late one evening on a train from Suceava. Early the next morning we returned to Suceava by train and picked up a rental car from Autonom. This was a Dacia Logan MCV station wagon that could comfortably carry the five of us plus our luggage when we later drove through the Carpathian Mountains to Sighişoara.

Autonom is the nicest car rental company I have ever dealt with! Instead of being treated as a potential source of expensive and unneeded added insurance revenue, we were welcomed as guests. There was no standing at a counter as chairs were quickly brought in for all of us to comfortably sit as I completed the paperwork. But first a bowl of candy was passed around and there were multiple offers of tea.

Then we returned to Gura Humorului along the highway and started visiting the monasteries!

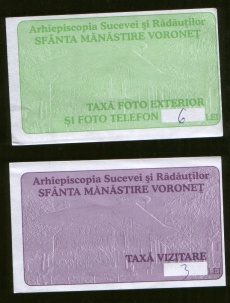

You pay just about 3 Lei to visit a monastery, plus twice that for a permit to take pictures — less than 3€ total.

The monasteries generally take the form of a walled compound with a church at the center. The church roofs have a distinctive conical shape with very broad eaves, the better to protect the intricate paintings covering the entire exterior.

The painted churches were built and painted between approximately 1487 and 1532. They have seen very little maintenance over the centuries. The Austro-Hungarian Hapsburg forces occupied Bucovina in 1786 and suppressed the Orthodox monasteries in favor of Roman Catholicism, closing many of these and for the rest limiting the activity and support to that of a small parish church. Then there was utter neglect for the most part during the years of communism and official state atheism. It is amazing that the paintings are in such good condition!

In March 1991, His Reverence Pimen, Archbishop of Suceava and Rădăuţi, signed an order to re-establish the Bucovina monasteries.

The church at Voroneţ, the Church of Saint George of the Voroneţ Monastery, was built in 1488. This makes it the oldest of the group along with the Church of the Holy Rood of Pătrăuţi. The interior paintings were completed in 1496.

This church exterior was painted a significant time after its construction, at a time in the 1530s when Petru Rareş commissioned artists to finish churches. Other churches, constructed later, were painted immediately after their construction finished.

This church was built between May and September 1488 by Stefan III of Moldavia, known as Stefan the Great. He built it to commemorate the victory over the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Vaslui in 1475, as he had promised to his spiritual advisor Daniel the Hermit. The Turks had seized Constantinople in 1453, and later renamed it as İstanbul. Stefan had pushed the Turks back south across the Danube.

Stefan the Great ruled Moldavia from 1457 until his death in 1504. Much of that time was spent fighting the Ottomans, fighting 36 battles and going 34-and-2.

The Battle of Vaslui may have been his most significant victory. 120,000 Ottoman troops opposed about 40,000 Moldavian troops plus smaller numbers of allied and mercenary forces. Stefan's forces inflicted over 40,000 casualties, causing the Ottomans to describe this as their worst defeat ever. Pope Sixtus IV later awarded Stefan the title Athleta Christi or Champion of Christ, and referred to him as Verus christiane fidei aletha or the True defender of the Christian faith. Stefan had hoped for military support from the Pope, but he received only 1,800 Hungarians and 2,000 Polish horsemen.

The broad eaves keep some of the sunlight and precipitation off the paintings, but really they are very exposed to weather and harsh light. I was surprised to find that it's usually the north faces that are more heavily damaged. The south facades tend to be in better shape despite exposure to sunlight for 500 years. The north sides are subjected to severe weather blown in from the Ukrainian and Russian steppes.

Here you can see that the exterior of the church has structural decorations in the form of shallow arches and niches in addition to the painting.

These small rectangular windows with crossed rods are Gothic era design, along with the receding pointed or shouldered arches above the interior doorframes. Other design elements are from the slightly later early Renaissance period.

Above is a standard representation that seems to appear on all the painted churches, the Tree of Jesse.

See the guy lying on his back at the bottom center of the picture at right, with a tree filled with people growing out of his stomach. That's Jesse.

Jesse was an Old Testament figure, the father of the shepherd turned king David. The "Tree of Jesse" metaphor comes from the prophet Isaiah who somewhat dismissively refers to Jesse as a "stump" in this translation:

The details of the tree are described in the exhausting list of begats making up the bulk of the first chapter of Matthew, a list that risks making anyone not into numerological geneology give up before getting through the first page of the New Testament:

The Tree of Jesse doesn't show all 42 generations, just the highlights, but it seems to always be on the church. It typically appears on the south facade, the long wall around the corner to your right as you face the entrance. Jesse will be somewhere near the bottom to fit in more levels of the tree.

But don't worry about not seeing all 42 generations of that tree, there are plenty of figures to more than make up for that! The numerous figures holding the fluttering white scrolls in the second picture above are going to be writers of gospel accounts and epistles, plus various early church writers.

Then the graphic narration transitions into some action scenes, Bible stories, and some scenes from early church history.

Here is a far more ornate Gothic window, and below that is a Δέησης or Deësis, known in Romanian as the Cinul. The standard Deësis shows Christ in Majesty or Χριστός Παντοκράτωρ, Christ Pantocrator, at center, holding a book and typically seated on a throne. He is flanked by the Virgin Mary at the viewer's left and John the Baptist at the viewer's right, both of them facing Christ with their hands raised in supplication on behalf of humanity.

In the second picture above, the designers thought "That's enough of that Prince of Peace imagery", and painted Saint George killing a dragon as Stefan the Great and his minions watch from a fortress. They then filled most of the rest of the buttress all the way to the top with martyrdoms of varied and gruesome methods.

The vivid blue background, still intense after centuries, is known as "Voroneţ blue". Art historians use that term in the same way that they use "Titian red" to reference a vivid shade used by that artist.

Some documents refer to the shade of blue here as "cerulean blue". The pigment was based on azurite, Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2, a deep blue mineral produced by the weathering of copper ore. The longevity of the painted churches' frescoes is due to their exclusive use of mineral based pigments.

Here is Grigoriye Mitropoli, or Григорїе Митрополи, giving a document representing the extension to the monastery church to Daniel the Hermit, by the time of this painting regarded as the saint Сты Диїнль.

The church was built on the location of Daniel's wooden hermitage, and he is buried in the church. So, the church at Voroneţ is formally considered to be a votive church, not a monastery church, and it has only a naos and the nave.

The painted churches feature the Last Judgement on the exterior of the entrance end of the church.

At the center of the very top row is a representation of God the Father, who rates a square halo. Below him, in a white circular full-body halo or mandorla, is a standard Christ in Majesty, or Jesus seated on a throne. Immediately below that is what might appear here to be an empty chair, but it is the Throne of Judgement or Hetymasia adorned with the cross and holding the Gospel and a white dove representing the Holy Spirit.

People are petitioning the three persons of the Trinity from both sides. Those who pass judgement, with gold halos, are put into the crowded entry queue to Heaven at lower left, where a few of them at the head of the line seem to be saying "Quit pushing!" to those behind them. One of them is Peter, no doubt telling them to quit jostling so he can use the key he's holding.

Within Paradise, with a light background and stylized plants, sit the Old Testament patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (holding the souls of the righteous in their laps), and John the Baptist and two angels making sure that Mary has a pillow to sit on.

The red river of fire and lava leads to Hell at lower right. As you will see in the below pictures, a line of Turks wearing turbans are bound for the torment of hell. Their queue of the doomed also contains other evildoers such as contemporary kings, popes and Jews, all of them being harangued by Moses. However, a few Turks and Jews are shown in the group lined up for entry into Paradise, making these artists relatively open-minded for their time.

The artists let their imaginations loose with the demons inventing new variations on the standard torments of skewering, cutting and burning, the people riding fish, and the unicorns and other mythical beasts.

The standard iconography is that those to Christ's right (the viewer's left) ascend to Heaven while those to Christ's left (the viewer's right) descend to Hell. Better visible at another monastery shown below, the hand of God emerges from a cloud beneath the Throne of Judgement to hold a scale weighing the souls of men. Demons try to tip it in the direction of Hell by piling on symbols of sin, while angels poke at them with spears and swords.

You could walk from Gura Humorului to Voroneţ, it's about seven kilometers so allow an hour and a half in each direction. But a car makes getting around much easier and you can see much more in a given amount of time.

To get there, take the highway out of Gura Humorului to the west. You will see signs for Mănăstirea Voroneţ directing you to turn left or south onto a small road leading toward the village of Stulpicani.

Driving in Romania

Speaking of driving, many people fear that driving in rural Romania will send you to a quicker Last Judgement, or at least it will serve as a torment of Hell. Research a trip like this, and you will find horror stories guaranteeing disaster.

Nonsense!

I wouldn't want to drive in Bucharest, but then I wouldn't want to drive in most large cities. That's why there are subways, light rail and buses.

Rural Romania is, well, quite rural. Plenty of haystacks but not a lot of traffic.

Some of the haystacks aren't so much stacks as they are hay curtains.

Yes, there are horse-drawn wagons. But if you come from Indiana, as I do, you are used to the far more dangerous Amish and their slower-moving black buggies.

The Romanians operate their wagons in ways that are far safer than the Amish in America. Romanians have no religious objections to lights and reflectors, but that doesn't matter much because (unlike the Amish) the Romanians get their wagons off the roads before it gets dark.

They also move briskly enough that they pose less of an obstruction.

The rubber tires on their wagons don't tear up the shoulders of the roads like the rigid wheels of Amish wagons.

Of course, once in a while you run into an oddity like a man pushing a wagon of sticks down the highway.

You do need to be careful when driving in Romania, but there is no need to worry too much.

Moldoviţa Monastery

On another day we're off to another monastery, at Moldoviţa. This is just north of the village of the same name.

We're at the intersection in Vama, between Gura Humorului

and Campulung.

Here we will turn north off the relatively large highway

onto a less major road, still two lanes and paved but not

as large or as used.

The lower road sign points the way:

Mănăstirea Moldoviţa 15 km.

After visiting that monastery, we will continue across the mountains to Mănăstirea Suceviţa.

Meanwhile, we have plenty of opportunities to buy local mushrooms and berries from these roadside vendors.

We pass through the villages of Frumosul and Dragoşa on our way to Vatra-Moldoviţei. All along the way we pass people walking along the road.

Mănăstirea Moldoviţa or Moldoviţa Monastery was built in 1532 by Petru Rareş, the illegitimate son of Stefan the Great.

Stefan the Great had died in 1504. Petru Rareş ruled Moldavia from 1527 to 1538 and again from 1541 to 1546.

It was Petru who commissioned artists to cover the interiors and exteriors of the churches with elaborate and colorful frescoes. Moldoviţa's frescoes were painted by Toma of Suceava in 1537, five years after the church was built.

Petru had this built on the site of a monastery built in the early 1400s and subsequently destroyed.

The monastery is operating today, home to several nuns as seen here. However, as you see below, Romanian churches are frequented by more than just the elderly.

Like the other monasteries, Moldiviţa is built as a walled fortress with towers at the corners of the walls.

The church's exterior frescoes are known for their use of vivid yellow, red and a metallic green. The green pigment was possibly based on local copper minerals.

Above, we see the narrow window at the center of the apse of the sanctuary, at the front of the church beyond the iconostasis and at the opposite end from the entrance. There are two representations of Christ above the window, a symbolic Lamb of God, and above that, the Virgin Mary holding Jesus on her lap.

On either side the paintings depict saints and other figures moving toward Christ.

We see saints moving in groups of one, two, and three toward Christ at the head of the apse.

Above is this church's Tree of Jesse.

Jesse is a little scuffed up, being down close to ground level, but that's him lying back at the bottom center of the picture.

Closer to the entry way, the south wall has a large multi-panel depiction of the "Siege of Constantinople", ostensibly commemorating the intervention of the Virgin Mary in saving Constantinople from Persian attack in the year 626.

However, this painting was intended to drum up support for Petru's planned campaign against the Ottoman Turks, who had seized Constantinople in 1453, 84 years before this scene was painted. It is no accident that the clothing and weaponry resemble that of 15th century Ottoman Turks far more than that of 7th century Persians.

Cannons in 626? Hah. The Chinese didn't discover gunpowder until the 9th century.

The siege is conveniently located near eye level to help with the recruitment process. Above that are some literally iconic scenes.

The one to left of center in the next picture is known in Greek as the Ανάστασις or the Anastasis, the Resurrection, and sometimes referred to as the Harrowing of Hell.

The standard or iconic details of the Anastasis are that Jesus is shown standing on a pair of crossed panels, the brazen gates of Hades or the "Doors of Death", which have broken and fallen to form a cross pinning the Devil or a figure of Death beneath them. Jesus is pulling Adam and Eve out of Hades, holding them not by the hands but by the wrists to illustrate the theological teaching that mankind could not pull himself out of sin but that it could only happen by the work of God. Meanwhile other Old Testament figures wait their turn.

The Anastasis appears at bottom center with many other scenes continuing all the way up to the eaves. The one to the left of the top of the elaborate window, above and to the right of the Anastasis, shows the Orthodox style cross.

There are three cross-beams on an Orthodox cross. The top one is the name plate which would have had "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews". Orthodox crosses traditionally bear "The King of Glory" here, Царь Славы or whatever that would be in Church Slavonic. Or, ІНЦІ, the Church Slavonic equivalent of the Greek Ίησοϋς ό Ναζωραίος ό Βασιλεύς τών Ίουδαίων.

The bottom crossbar is slanted in representations influenced by the Russian church, slanting down to the viewer's right. The idea, as in the left versus right of the iconic Last Judgement representation, is that those to Christ's right ascend to Heaven while those to his left descend to Hell.

We're looking out of the porch toward a building constructed against the outer wall. Let's go in!

The inside is just as heavily decorated as the exterior. As usual in an Orthodox church, the central dome bears a Christ Pantocrator, Greek for "All-powerful" or "Ruler of All".

The iconostasis of an Orthodox church divides the nave from the altar area.

An iconostasis is built and decorated following a a very specific design. The row of icons about eye level to either side of the central doorway is called the worship row. The icon to the right of the central door shows the saint or the event of the church's dedication. The icon to the left typically shows the Panagia, a specific pose of Mary with the infant Jesus.

If there are icons on the doors, typically they show the Annunciation at the top and then the four gospel writers below that.

Above the central door is the place for the Communion of the Apostles.

Then, at least in larger churches, there may be four rows of icons spanning the entire iconostasis above the doors. The first is the Deësis (or prayer or supplication) row, with Christ in Majesty or Christos Pantocrator at the center. He is flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, with archangels Michael and Gabriel flanking them, and other saints spreading to either side.

The second row up would show the great liturgical feasts, twelve or so depending on the size of the iconostasis.

The third row up would show the Virgin of the Sign (Mary with both hands raised in prayer, with a circle on her breast showing Jesus with his right hand raised in blessing) at the center, with Old Testament prophets extending out on either side.

The top row would show the icon of the Hospitality of Abraham (the three angels who visited Abraham at Mamre, sometimes called the Old Testament Trinity) with the Old Testament patriarchs from Adam to Moses on either side.

If you want even more details, see the paper "Icons in Theory and Practice" by Margaret E. Kenna, History of Religions, vol 24, no 4 (May 1985), pp 345-368. Also see the book The Meaning of Icons by Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, St Vladimir's Press, 1982.

Amazon

ASIN: 0913836990

As for getting to Moldoviţa, if you don't have your own car you can get there out of Gura Humorului in the maxitaxi, the shared van. It has no set schedule, it runs when an adequate number of people have shown up. Look for a group of people gathered in front of the big hotel at the center of town.

Suceviţa Monastery

Now we will continue to our next destination, shown in this road sign: Mănăstirea Suceviţa or Suceviţa Monastery.

A small road will take us northeast through the mountains. Along the way we passed through a village with signs written in Ukrainian. Although we were very close to the Ukrainian border the whole time we were in Bucovina, this was the only time I noticed Ukrainian in use.

Some of what you see here is in the Ukraine. How much? I don't know.

The furthest out hills visible here are definitely across the Ukrainian border, as we're no more than ten to fifteen kilometers away from it here.

Suceviţa Monastery is built as a very sturdy defensive structure. Its main courtyard is about 100 meters on a side, and the walls are six meters tall and three meters thick.

The monastery was built in 1585, and the church was painted around 1601. So, Suceviţa is one of the very last monasteries to be decorated in this elaborate style.

The distinctive aspect of the artwork here is the depiction of the Virtuous Ladder filling a large section of the north facade.

You can see it above in the center, and closer views below. Angels with red wings assist the righteous climbing the angled ladder to heaven. The rungs inscribed with alternating monastic virtues and sins. Sinners fall between the rungs to the dark devils and Hell. The message is the danger of complacency as some fall from near the end of their struggle.

Below we see a Russian influence from over the nearby border. See the depiction of the five-domed Russian style church between the two ornate windows. It shows Saint Andrew's vision of the Virgin's Protective Veil. Andrew had a vision of Mary spreading her veil over the congregation inside Constantinople's Haghia Sophia, an immense church that looks neither Russian nor Romanian.

This monastery's version of the Tree of Jesse is very distinct. However, the patriarch looks rather tired or bored here.

The vivid green pigment is copper-based, possibly made from local deposits.

The apostles and saints aren't just moving toward Christ, above the window at the head of the apse of the sanctuary, they're hurrying, almost running.

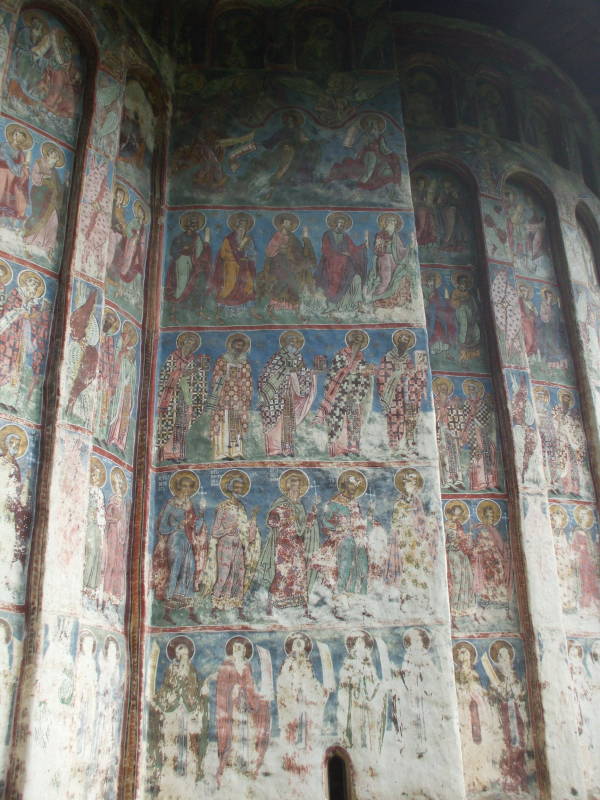

The hierarchy is: Angels and seraphim at the very top, archangels and prophets below them, holy men and martyrs below them, and military saints and ancient philosophers along the bottom tier.

Here is the destination of all those hurrying saints: several representations of Christ along the center of the apse. The third one down is the standard enthroned Virgin Mary holding baby Jesus on her lap.

Humor Monastery

The final monastery we visited was Humor Monastery, just five kilometers north of Gura Humorului. Like Voroneţ, it would be feasible to walk there from town if you allow 60 to 90 minutes in each direction. This monastery features the Church of the Dormition of the Virgin.

It is pronounced like "WHO-more", not like "HUE-more". Similarly, the town's name is pronounced "GOO-ra who-MORE-oo-louie". More or less, anyway.

There is another "Siege of Constantinople" here, again ostensibly commemorating the repulsion of a Persian attack on Constantinople in 626, but really recruiting fighters and raising support for a campaign against the Ottoman Turks.

Above and below you see the supposed "Persians" looking exactly like contemporary Turks.

The artistically distinctive feature here is the use of reddish brown pigment.

The frescoes were painted in 1535 by the master painter Toma of Suceava, two years before he painted those at Moldoviţa.

Petru Rareş is said to have also built this monastery, but his chancellor Teodor Bubuiog really deserves the credit. There had been a monastery here before, dating from around 1415, but it had been destroyed. Teodor built this one over its foundation in 1530, and then had Toma do the paintings in 1535.

Here is a detail of the Last Judgement. Jesus in a full-body mandorla at the top of the frame, the Throne of Judgement with the Gospel and the Holy Spirit as a dove below him, and below that, the hand of God holding a scale that weighs souls to decide which way they go. Demons add weights representing sins to tip the balance.

We see some people approaching judgement. We can assume that it will not go well for those wearing turbans.

That's Moses waving his scroll and scolding them.

Along the river of fire and lava leading into Hell we see another person riding a fish near sea creatures including an octopus and a lobster, and on land, an elephant. The woman riding a fish and holding a ship symbolizes the sea giving up its dead for judgement.

The entry into the outermost room, the pronaos, is immediately below the Last Judgement between Heaven and Hell. This entry door is in a wide porch open with archways on the other three sides. Let's go in!

Tombs of two abbots are in the floor of the pronaos.

All the way into the naos or nave we reach the iconostasis. That's the typical Panagia icon to the left of the central door leading to the innermost sanctuary.

Here we have turned to look out from the naos through the tomb chamber and pronaos to the porch.

All of these monasteries were closed in 1786 or soon after when the Austro-Hungarian Hapsburg forces occupied Bucovina. They suppressed the Orthodox monasteries in favor of Roman Catholicism.

This monastery and its church became a simple Roman Catholic parish church, and that in turn was suppressed by the communists starting in 1945. This monastery was re-established in 1990 as a working church and convent for nuns dedicated to the Dormition of the Virgin Mary.

Gura Humorului

We stayed at the wonderful Hilde's Residence, just a short walk from the station. A double room was €45.

2 Sipotului street

+40-230-23-34-84

http://en.lucy.ro/

47°33'07.2"N 25°52'50.3"E

Just walk through the station and out to the main road, turn left, and it's a short distance ahead on the right side of the road.

This is one of the nicest places I have ever stayed. I suppose it is what is typically called a "boutique hotel", with each room decorated in a unique style. The meals here are wonderful. See the page on The Romanian food and drink for many pictures from breakfasts and dinners at Hilde's.

The distinctive architecture of the houses throughout Bucovina was interesting.

This large new church is in the center of Gura Humorului.