The Road to the Isles

Staoineag Bothy to Lùibeilt

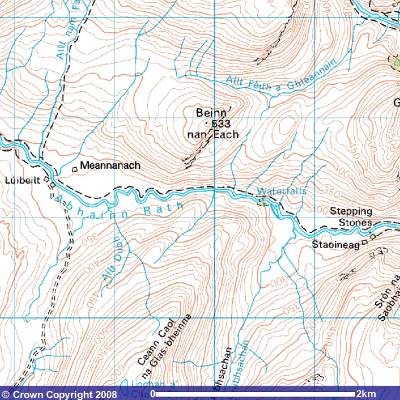

I'm on the Road to the Isles path from Corrour railway station on Rannock Moor, heading toward Glen Nevis and onward to Fort William. Here begins what I found to be the most discouraging part of the hike. Just east of Staoineag you cross a broad and extra swampy area where Allt Gleann na Glubhsachan flows into Abhainn Rath from the south. This is most of the way from Staoineag to the waterfalls marked here, Allt Gleann na Glubhsachan is the large stream flowing in from the south in the middle of that area. The Ordnance Survey map shows two tributary streams joining Allt Gleann na Glubhsachan.

The reality on the ground, or really in the swamp as there isn't a lot of solid ground, is much worse. The roughly triangular flat area is sort of a delta of Allt Gleann na Glubhsachan, combined with various other branching streams, and pools, and generally an awful lot of water and not much ground.

Abhainn Rath from Staoineag Bothy to Luibùilt

Now, I had hit upon the fairly useful idea of planning ahead for this trek by bringing along some reasonably sturdy sandals. My plan was to put them on "for the boggy parts", foolishly thinking that there would just be short boggy sections here and there, but for the most part, The Road to the Isles would be, well, sort of a road.

Silly me.

I put the sandals on before crossing the tracks at Corrour Station, and only switched back to my boots when I hit the rough pavement at the Glen Nevis roadhead. Sam Walton's slave-labor sandal makers were having a good day in the factory on that day, I tell you, because some US$18 WalMart sandals stood up to the entire trek across the highlands.

The sandals let me more easily wade through areas where bogginess transitioned through swampiness into outright water with hummocks of grass here and there.

All the same, I was trying to keep out of water above knee deep. I wasn't always successful with that, but that was the general plan.

Once around and through that swampy area, it was on eastward along Abhainn Rath, past the waterfalls shown on the map, continuing to the ruins of the Lùibeilt (or Lùb Eilde) estate. There's another bothy, Meannach Bothy, north of the stream across from Lùibeilt. Not quite as nice as Staoineag, it would provide another shelter if you wanted (or needed) to stay overnight along the way.

You can see that the map indicates a path on the north bank of Abhainn Rath, while I was following the south bank. Again, I would follow the same route the next time. There were a lot of streams coming down the steep slopes from Beinn nan Each, more than are shown on the above map. Plus, the north bank was freqently a steep bank sloping right down into the stream. That side looked like a much more likely cause of a sprained ankle or knee.

Not that any of it was easy walking — much of the path was on uneven ground with no level steps.

Amazon

ASIN: 0319239128

Amazon

ASIN: 1741042038

Continuing west along Abhainn Rath from Staoineag Bothy toward Lùibeilt. This is the view from just beyond Staoineag Bothy, before things get oppressively swampy.

Things flatten out and get boggier.

At least there weren't midgies. I can't imagine crossing this area if the midgies were in full swarm.

The Highlands have a lot of peat.

What's peat?

Peat used to be vegetation.

After a few millenia, peat may become lignite, which might then become coal after several more millenia.

In more detail, peat forms when plant material, usually marshland vegegation, is inhibited from decaying fully because of acidic and anaerobic conditions. Most modern peat bogs formed in high latitudes about 9,000 years ago, after the end of the last ice age and the retreat of the glaciers.

The peat areas of the Highlands have layers of this black organic material.

Peat can be cut in thick blocks and used as fuel or building material. It's a limited resource, taking thousands of years to form the peat bogs found today and typically increasing by about one millimeter per year. So, peat cutting is now carefully limited in Scotland. In Ireland and Finland, it is extracted on an industrial scale and used to power electrical generation plants.

Peat.

Lùibeilt and Meannach Bothy are visible in the distance.

Peat is soft and easily compressed — try walking across a peat bog if you don't believe that! It's possible to force much of the water out under pressure, and then use the peat as fuel. It has traditionally been used for domestic heating and cooking in Scotland.

Peat was traditionally used to dry the malted barley used to produce Scotch whisky, providing its distinctive smoky scent and flavor. Different regions (Highlands, Speyside, Islay, and more) had different traditions for how they went about this, making the whisky from some regions, especially Islay, peatier.

But I'm afraid that these days the major Scotch producers buy their malted barley from large providers, and the phenols producing the smoky scent and flavor are artificially added during the malting process.

Lùibeilt and Meannach Bothy finally came into view.

The ruins of Lùibeilt estate.

Lùibeilt (or Lùb Eilde) estate must have been quite nice in its day. But it's a wreck now — the roof is completely gone and some of the walls are partially down. Lùibeilt is at NN 263 683.