Herbert O. Yardley's Suspicious Restaurant

Herbert Yardley

Herbert Yardley was an American code-breaking hero in the 1910s and 1920s. He lost his job when the Secretary of State was offended by the American ability to break foreign codes and ciphers. Yardley wrote a book in 1931 exposing some of his accomplishments a decade before, leading to his being considered a traitor to this day — unfairly, it now seems. Yardley ran a restaurant in Washington, D.C. during World War II, where he came under suspicion for maintaining a meeting point for Fascist agents. But an FBI investigation concluded that there was nothing to the allegations.

See my page about Yardley's "Black Chamber" operation in New York for details of his life and career through 1931. The short version is ...

Herbert Osborne Yardley was born in Worthington, Indiana in 1889. His father, a railroad station master and telegrapher, taught telegraphy to Herbert. After graduating from high school in 1907, Yardley worked as a telegraph operator for the railroad while teaching himself poker, especially the probability involved.

Yardley became a telegraph operator for the federal government, starting as a code clerk in the State Department, where he was able to break the current U.S. government codes, including that used by President Woodrow Wilson and in use for over ten years.

Herbert O. Yardley, 1889-1958

The U.S. entered the war in April 1917, and Yardley was sent to the U.S. Army Signal Corps. He was named head of MI-8, or Military Intelligence, Section 8, a special bureau dealing with cryptology. Yardley's small group broke almost all of the German diplomatic and military codes within a few months.

General Marlborough Churchill, head of U.S. Army Intelligence (and a distant relative of Britain's Winston Churchill), managed to persuade State Department officials to fund a covert and deniable post-war cryptanalysis operation. It would analyze and attack foreign codes and ciphers, but for legal and operational security reasons it was to be located in New York, not Washington.

MI-8 operated covertly in a series of brownstones in New York. Ties to the government were cut. Employees had no civil servant status and were paid in cash from a secret payroll fund.

The U.S. State Department and War Department had special arrangements with commercial telegraph companies, including at least the Western Union and Postal Telegraph companies. During the first year the work focused on Latin American countries plus Germany, Japan, and Spain. The Black Chamber soon broke the codes of the Чека or Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police that had replaced the Czar's Охрана or Okhrana and which eventually evolved into the KGB and today's ФСБ or FSB.

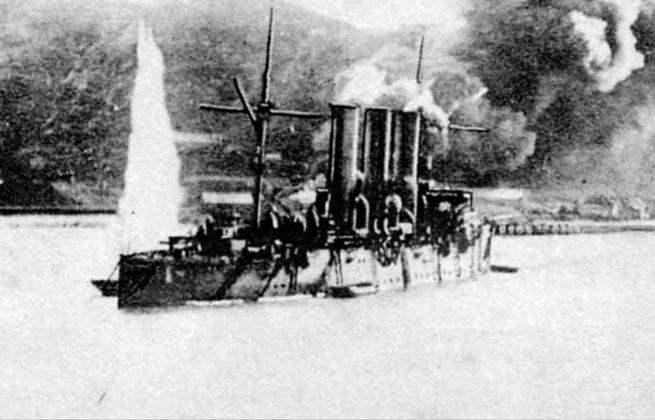

The Russian cruiser Pallada under fire at Port Arthur, Manchuria, now Lüshun, PRC, before being seized as war booty by Imperial Japan.

The Black Chamber was then asked to attack the Japanese diplomatic codes. They quickly broke the Japanese ciphers, contributing significantly to the partial containment of Japan at the 1921 Washington Naval Conference.

The Black Chamber decrypted the intercepted messages between the Japanese emissaries and their home government. What was even more sensitive was that they were also breaking the messages of American allies. The U.S. negotiators had a huge advantage at that conference.

Despite its successes and obvious utility, the State Department significantly reduced the Black Chamber's funding in 1924. Then, in 1929, Henry L. Stimson was named Secretary of State. Stimson was offended by espionage and any type of covert action, and he imperiously and naïvely issued the infamous directive "Gentlemen do not read each other's mail." The American Black Chamber was shut down on 1 November 1929.

Yardley was out of a job and unable to find another. This wasn't surprising, as the few organizations looking for his set of skills had mostly been targets of his recent cryptanalysis.

He then wrote The American Black Chamber, a book that became immensely popular and simultaneously brought him harsh criticism lasting to this day.

Amazon

ASIN: 1591149894

The American Black Chamber was denounced by the U.S. government as having given away American secrets. Not the secrets of how to perform cryptanalysis, but the secrets about how and when it had been applied — not only against likely adversaries such as Japan, but also against U.S. allies. This led to Public Law 37, signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, criminalizing any such future exposure.

Yardley next wrote a book titled Japanese Diplomatic Codes: 1921-1922, but the government cited Public Law 37 and seized the manuscript before it was printed. The manuscript was classified until 1979, when it was finally declassified.

Amazon

ASIN: 0395346487

Yardley went to China in 1938 and worked with Chiang Kai-shek's intelligence bureau until late 1940. Another book of his memoirs, The Chinese Black Chamber, was declassified and published in 1983. In early 1941 he was in Canada helping establish a cryptanalysis bureau. After the U.S. entry into World War II in December 1941, Yardley returned to the U.S. and was given a government job shuffling meat inspection forms for the Office of Price Administration. Meanwhile, William F Friedman and others were breaking German and Japanese ciphers, using Yardley's unpublished manuscript of "Japanese Diplomatic Secrets" at least for some initial guidance.

David Kahn has written a typically excellent biography of Yardley, The Reader of Gentlemen's Mail. Kahn's book and a Cryptologia article, "Tales of Yardley: Some Sidelights To His Career" (Louis Kruh, Cryptologia 13:4, 1989, pp 327-358), have been about the only trustworthy sources of information on Yardley's career.

Amazon

ASIN: 0300098464

In January, 1942, an FBI file reveals that Colonel William "Wild Bill" Donovan, FDR's Coordinator of Information (soon to become the Office of Strategic Services or OSS) was planning to (re-)establish an American Black Chamber and to place Yardley in charge of it.

However, by mid-summer of that year, Yardley was under FBI suspicion. He was running a restaurant at the time, the Rideau Restaurant, at 1306 H Street, N.W. That location would be about where the blue awnings are seen directly ahead in the picture below. He had purchased the restaurant, formerly the Goodacre White Coffee Pot, immediately upon returning to Washington in January of 1942.

We're looking west, across 13th Street at the building on the southwest corner of 13th and H. The building there at the time of the Rideau Restaurant has been replaced. 13th and H is an elongated open square where New York Avenue passes through the intersection at a shallow angle, as shown by the sides of the large church and the building behind it.

This location is just about 3 blocks east of the Treasury building, and not much further than that from the White House. If we were to walk ahead to New York Avenue, we could see the Treasury building.

A confidential internal memorandom on the letterhead of the Military Intelligence Division of the War Department, dated July 23, 1942, reported:

Information has been received from a reliable source that

subject [Yardley] is operating a restaurant at 1306 H Street,

N.W., Washington, D.C., which is being used as a "hang-out"

for pro-Axis persons.

Subject is reported to be very disgruntled with the War

Department and with the Military Intelligence in particular

because they will not avail themselves of his services.

The Counter Intelligence Corps launched a detailed investigation, including undercover surveillance at least 13 times between August 6 and August 28, 1942. The undercover surveillance involved watching the restaurant, patronizing it, observing other customers and eavesdropping when possible, and engaging the employees and Yardley himself in conversation in an attempt to obtain information. On at least two occasions the agents occupied offices on higher floors of neighboring buildings to use powerful binoculars to examine the second-floor apartment where Yardley lived above the restaurant.

The buildings of the early 1940s are gone. 1306 would be about where you see these blue awnings on the building currently on the southwest corner of 13th and H.

The CIC investigators also conducted interviews with eight informants, and visited the Alcoholic Beverage Control Office, the Civil Service Commission, the Department of State, the Department of Justice, the War Department, the FBI, and the Metropolitan Police Department, all to check any files they held on Yardley.

Then they visited the Washington Times-Herald to review their clipping file on Yardley, and went to Yardley's bank to inspect his record of deposits and withdrawals dating back to August, 1940.

A five-page report was released on September 7, 1942, concluding that there was nothing to this case but throwing in plenty of extra innuendo and a little misspelling:

Nothing was revealed during this inspection pertaining

to suspected disaffection of the Subject or any indication

that the Rideau Restaurant is being used as a meeting

place for pro-German sympathizers.

[...]

This agent recommends that the case be closed as the

Subject is not a member of the War Department or the Army;

this agent feels that Yardley is a very shrewd man and

that he is capable of performing subversive acts against

the Government if he desired.

It seems difficult to believe that this man, with his

background of cryptography, codes and ciphers is satisfied

to remain inactive during the present world crisis.

It is highly possible for Yardley to use the above

restaurant as a front for some other endeavor.

[...]

If [...] this case is re-opened, it is recommended by this

Agent that an Agent of Nordic appearance be used to enter

into conversation with Subject, as this Agent, who is

dark complexioned, failed to converse with Yardley,

who appears to have a dislike for Semetics. [sic]

Yardley gave up the restaurant in December 1942, having owned and operated it for most of that year.

The church on the square is the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church.

The church itself was established in 1803, and initially held its services in the U.S. Treasury Building.

President Abraham Lincoln and his family had a pew here the first Sunday after his inauguration in March, 1861. This was just six months after the newly constructed church had been dedicated. In that day you rented a pew, the Lincolns paid $50 per year. Pew rent was the main source of financial support for the church through the 1800s.

The current structure dates from 1951.

Ladislas Farago's 1967 book The Broken Seal: The Story of "Operation Magic" and the Secret Road to Pearl Harbor, alleged that Yardley sold U.S. cryptologic secrets to the Japanese in 1928. Many writers, including the author of an NSA monograph in 1981, have accepted Farago's claims. However, John Dooley's article "Was Herbert O. Yardley a Traitor?" (Cryptologia, 35:1, 2011, pp 1-15) seems to conclusively show that there is no historical basic for Farago's claim.

Farago's claim is based on an internal memorandum from the Japanese Foreign Ministry in June 1931, ten days after the publication of The American Black Chamber. Farago says that during the summer of 1928 (since revised by researchers to the summer of 1930), Yardley asked a Japanese journalist to organize a meeting with the Japanese Ambassador to the United States in which Yardley was to offer "valuable information that would interest the Japanese embassy. Farago wrote that Yardley met with Japanese counselor Setsuzo Sawada and offered to turn over a large number of decrypted diplomatic cipher messages, the techniques used to break Japanese diplomatic cipher systems, and details of the diplomatic cipher systems of other countries including the U.K., all of that in return for $10,000, later negotiated down to $7,000.

Amazon

ASIN: 1594161712

Farago's basis for these allegations is a memorandum from Shin Sakuma, chief of the Foreign Ministry's Telegraph Section, to the Japanese Foreign Minister Shidehara, dated on or about June 10, 1931, and supposedly found in the microfilmed archives of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This Sakuma Memorandum references a Telegram #105 sent in June 1930 from the Japanese embassy in Washington to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs office in Tokyo.

However, this Telegram 105 cannot be found in the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (JMFA) microfilm files held at the U.S. Library of Congress.

Kahn's conclusion is that Yardley never sold anything to the Japanese, and the story was fabricated by the Japanese Foreign Ministry to discredit Yardley while saving face for them.

Dooley's more recent search for documents supporting Farago's accusation did reveal something rather startling, but rather than Yardley it was about William Friedman, the man who assumed the role of American cryptologic leadership.

This is Secret Telegram Number 48, dated March 10, 1925, from Japanese Embassy counselor Isaboru Yoshida to the Foreign Ministry [reel UD-29, frames 72-73, JMFA microfilm collection, U.S. Library of Congress]:

Telegram Section

Confidential #48

Date: March 10, 1925

From: Isaburo Yoshida, Acting Ambassador to the US

To: Kijuro Shidehara, Minister of Foreign Affairs

Re: Telegram codes

Mr W. Friedman,

an American, from Cornell University seems very skilled in

breaking codes; for he was engaged in breaking codes at

the war in Europe (i.e., WWI), and he is now working

for the US Army.

When he came to see me recently, he mentioned that

the US Army had no difficulty breaking codes.

In order to prevent this, we have no choice but change

codes very frequently.

I am sending this note for your information.

Dooley points out that Yardley is not mentioned at all, but here was Friedman, then the War Department's Chief Cryptanalyst since 1921, talking to a Japanese diplomat and boasting of the US ability to break Japanese codes.

As Dooley concludes, Yardley was a good but not great cryptanalyst, his greater skill was in organization and management. He was insecure, envious, and prone to inflating his own importance. However, there seems to be no evidence of any traitorous activity on his part. The only document that has been found is a memorandum that seems to have been an effort to control the damage done by Yardley's book to the reputations of the Foreign Ministry in general and Foreign Minister Shidehara in particular. He ends by quoting Kahn, "Yardley was a rotter, not a traitor."

Yardley went on to write and co-write several magazine articles and some thrillers, The Blonde Countess, Red Sun of Nippon, and Crows Are Black Everywhere, featuring fictionalizations of his exploits overseas and some of the world of his Black Chamber, although it is still debated as to how much he actually wrote of some of these. See the journal article, "Who Wrote 'The Blonde Countess'? A Stylometric Analysis of Herbert O. Yardley's Fiction", Cryptologia, 33:2 (April 2009), pp 108-117. The movie Rendezvous was based very loosely on "The Blonde Countess".

Well after the war, in 1957, Yardley published "The Education of a Poker Player", describing a powerful system for playing real poker where an understanding of probability is required. Sales were strong, but Yardley died in 1958.

Another source of information on Yardley is "The Many Lives of Herbert O. Yardley", published in the NSA's "Cryptologic Spectrum" journal in 1981. As you might imagine, the tone of that article is disapproving at best. Its author seems to have simply accepted Farago's claims despite the lack of supporting information, despite having introduced Farago's book as "full of inaccuracies and questionable conclusions." But his opening sentence is, "This story may be only 80 percent true."

The NSA has other full books available on-line in their collection of World War II history, among other areas of their on-line history library.

Other travel locations

Back to the U.S.A. Travel pageBack to the International Travel Recommendations