Knossos — 𐀒𐀜𐀰

The Minoan Palace Complex at Knossos

Knossos or

Κνωσός

has been called the first European city and

the home of the first European civilization.

The site was settled around 7000 BCE in the

early Neolithic period

as a small settlement of 25–50 people.

That grew to about 200–600 people by the

Early Neolithic of 6000–5000 BCE,

and 500–1000 by the Middle Neolithic of

5000–4000 BCE.

By about 2000 BCE it had become an urban area of up to

18,000 people.

At its peak shortly after 1700 BCE, the population of the

complex and the surrounding city had grown to about 100,000.

The first "palace" complexes were built soon after roughly

2000 BCE.

These were destroyed, almost certainly by earthquakes,

before roughly 1700 BCE.

The palace complexes were rebuilt on a grander scale,

leading to about 1650–1450 BCE being the

peak of Minoan prosperity and power.

The settlements of all these periods were built on

top of each other.

We know very little about the people who lived there.

We have no idea what they called themselves.

We call them "Minoan" because of myths

recorded significantly later about a King Minos.

An initial step in what became a

modernist interpretation and re-creation

of the site was boldly saying that King Minos

must have been real, and so this must have been his palace,

and so these were "the Minoan people".

We don't really know anything about what their language

or maybe languages were like.

They had a written language but they seem to have only

used it for business — listing inventory,

making a receipt for a sale, labeling the owner or

the contents of a clay container.

No history, no myths, no religious texts, and no basic

"Here is what it was like to live in this time and place."

Whoever they were, they abandoned the Knossos palace complex

in the Late Bronze Age, around 1380–1100 BCE.

The Mycenaeans (the Greeks in the story of the Trojan War)

then took control of this site and other former Minoan sites

and trade routes.

In the mid 20th century we finally figured out how to

read its name in the Linear B syllabary script

used for Mycenaean Greek:

𐀒𐀜𐀰

or KO-NO-SO.

Knossos is great to see, but to make sense of it

and get a gnosis of Knossos,

or at least to avoid making nonsense of it, you have to

be aware of how much we really do not know about it.

And, how much of what we've been told is wrong.

This long page has almost as much about the overly inventive

re-imagination of the site and the Minoan civilization as

it has about what you see at Knossos.

See Sir Arthur John Evans's

six-volume excavation report

if that's what you're looking for.

Know that we don't know.

Έπιστήμη

–

λογία.

Epistemology.

You can take bus #2 from central Heraklion to

the Knossos site for just €1.50.

Buy your ticket at the machine found at some of the stops

or from a nearby kiosk,

otherwise you must pay an extra Euro to buy your the ticket

on board the bus.

I stayed at the Intra Muros Hostel which is, just as its name says, within the massive Venetian-era walls of the old city of Heraklion. Or Iraklion, or Iraklio, or Iraklia, or whatever. The name of the city is really Ηράκλειο and there are various way to spell it in Latin characters.

The Intra Muros is near Ναός Αγίου Μηνά or Naos Ayiou Mina, the Church of Saint Minas, which is on a major street that makes a loop within the old walls while changing its name along the way. On that street, just up from the church and a few blocks from the hostel on tiny winding back streets, is a nice coffee shop. I got breakfast here every day.

Here I'm having a tiropita or cheese pie, and a double Greek coffee.

Then a second double Greek coffee as I beat down the jet lag and review some background on Knossos.

Deconstucting a Modernist Misadventure

€1.50 bus ticket. If you buy it from a machine, look at the nearby sign and see which zone you will travel to. For me, from the central old city, this was the πορτοκάλι or portokali, the orange zone. Or if there is no machine at the bus stop, look for a nearby kiosk selling cigarettes, drinks, and snacks and see if they don't also sell bus tickets.

We don't know very much about the history of Knossos, or at least not as much as we thought we knew for a while.

We do know about the history of the early 20th century analysis and interpretation of Knossos, and that gets pretty strange. And interesting! A visit here will show you some things about life in a mysterious civilization over 3,500 years ago. And it will also demonstrate the origins of modernist art and architecture in the early 20th century.

The initial scientific investigation of Knossos, or at least what passed for that, ran from about 1900 through 1936. That placed it after Greek independence, and soon after a series of Balkan wars and violent uprisings in Crete, and then during World War I and the build-up to World War II. It was a grim time.

The principal investigator was Sir Arthur John Evans. He was deeply influenced by the events of the time.

Much of what he "discovered" at Knossos was really his preconceptions and idealized dreams of what could or should have been. He worked hard to force what he found into what he wanted to have found. Evans's visions, inventions, and forgeries became the official description of Knossos and the Minoan civilization. The deciphering of Linear B in 1952 led to broad questioning of some of his conclusions, and much more was debunked in the following decades. Joseph Campbell published his Occidental Mythology, Volume 3 of his Masks of God series, in 1964. It's of a transitional period, citing Evans throughout its second chapter but cautiously so in places.

The paper Stone Age Seafaring in the Mediterranean [Hesperia 79 (2010), pp 145-190] pushed the arrival of humans on Crete much further back than previously thought, to at least 130,000 years ago. The evidence for that was found on the south coast, and so probably would be associated with explorers from the north coast of Africa. That more than doubles the known age of sea-crossing migrations, a record previously held by human arrival in Australia about 60,000 years ago. Also see a New York Times article summarizing the discovery.

The paper A European population in Minoan Bronze Age Crete reports that mitochondrial DNA studies have shown that Minoan-era Crete was not occupied by explorers from the coast of Egypt and Libya. Instead, the same Neolithic farmers who migrated out of Anatolia into Europe around 7000 BCE also crossed the Mediterranean to Crete at the same time. There is still debate over whether they brought an Indo-European language along with their agricultural techniques.

We have very little history of the so-called Minoans, but the history of archaeology itself through this time is luridly fascinating. Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Karl Jung and several of his followers, several modernist and surrealist artists including Pablo Picasso and Giorgio de Chirico, modernist architects including Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier, and many others played large roles in the analysis and interpretation of Knossos, and were in turn influenced by it. The book Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism walks you through Evans's creation of his imagined Knossos, "pacifist and matriarchal, pagan and cosmic."

Evans imagined a King Minos who was a famously benevolent law-maker and not a notorious tyrant; his palace featured a dancing floor and not a monster's prison. For Evans, any open space was possibly — probably — certainly — the Dancing Floor of Ariadne. I visited Knossos the first time I went to Crete. I read that book before returning, and found that I also enjoyed and got a lot out of a return visit to Knossos, just in a very different way.

The book 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed is also very useful for understanding the end of the Bronze Age.

The Discoverer

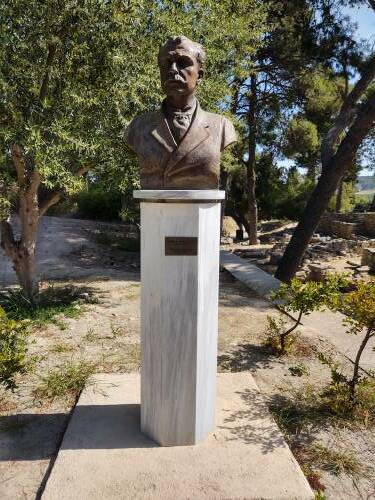

Μίνως Καλοκαιρινός or Minos Kalokairinos, an amateur archaeologist, discovered the site in 1878. The authorities on Crete were quickly shutting down any archeological work because it was clear that Crete would eventually, hopefully soon, become independent from the crumbling Ottoman Empire. Anything found during Ottoman control would be taken away to the Empire's collection in İstanbul, so leave it in the ground until Crete was independent or part of Greece.

Minos Kalokairinos.

Bust of Minos Kalokairinos at Knossos.

There is little recognition of Kalokairinos today, but there is a bust of him at the site he discovered.

The Excavator and Dreamer

Then along came Arthur Evans, eventually to become Sir Arthur John Evans. It was a different and much earlier time in archaeology and science in general. If you think Dr Henry "Indiana" Jones was reckless and sometimes unethical, get a load of this guy. His hypotheses, which became his conclusions with or without evidence, were based on the art of Renaissance Italy and ancient Egypt, on languages and scripts of the Levant, and most dangerously, on some of the more ancient myths.

Sir Arthur John Evans, from Volume IV, The Palace of Minos at Knossos, Part I, 1935

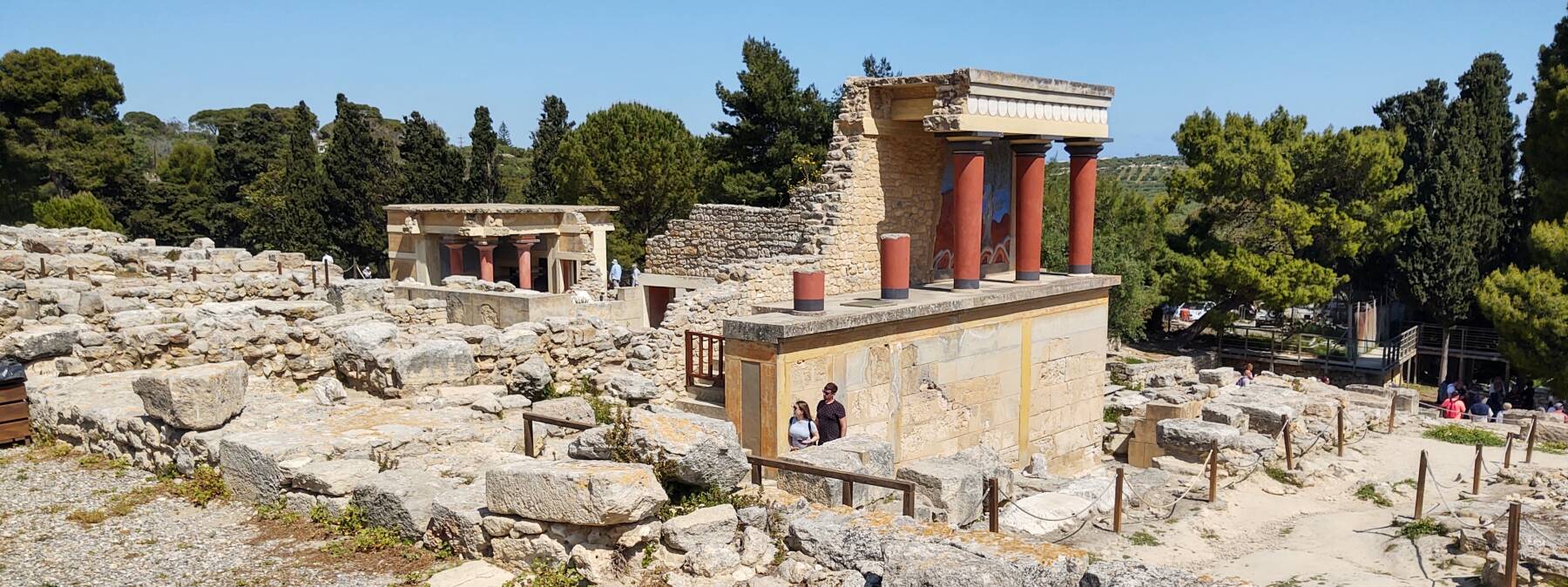

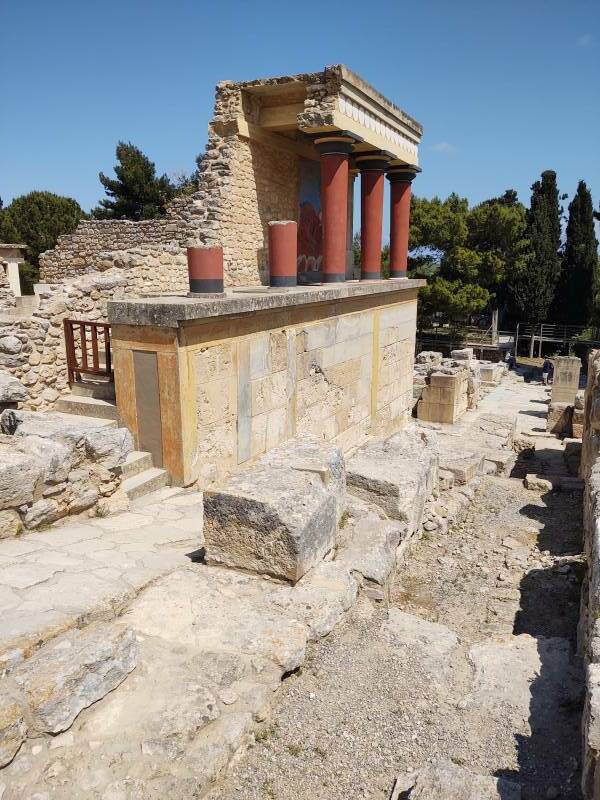

Much of what you see at Knossos today in the way of architecture and art are what Evans variously called his "reconstructions", "reconstitutions", or "re-creations". Meaning that this is what he thought it should have looked like.

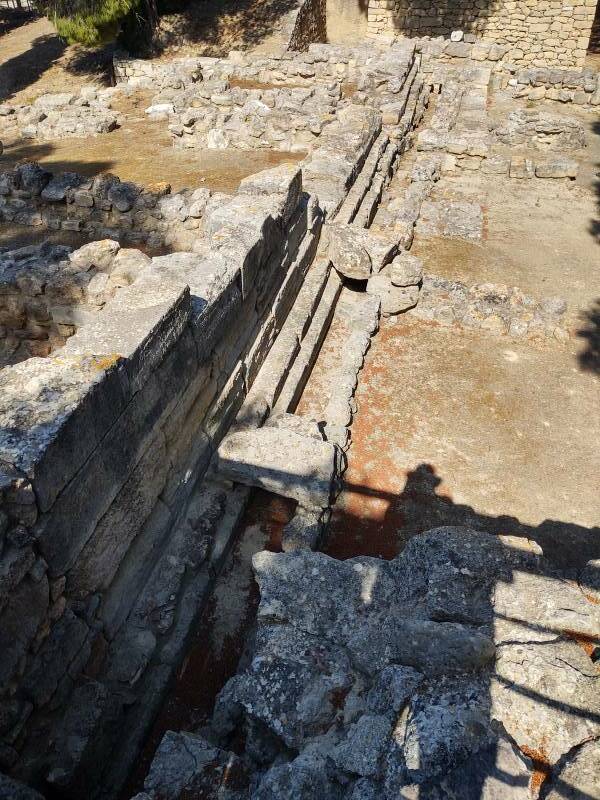

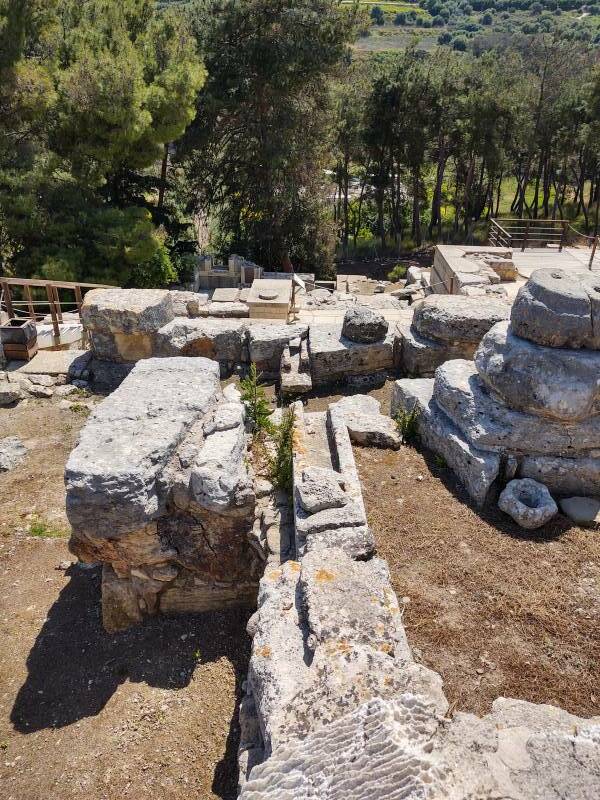

Structural forms and especially the infrastructure, however, are more solid. The Minoans had surprisingly advanced water and waste handling systems, like the stormwater drain line seen above. Similarly advanced systems were found by other researchers at other Minoan sites. More on this later.

As for the structures and architecture, I think that we can (at least mostly) believe what Evans's workers discovered below the ground level when they were excavating. The colors are based on fragmentary pigment remains.

But I now realize that what protrudes above the ground today, like what you see above and below, are fanciful structures designed by Evans. And the frescoes, especially their depictions of people, are almost entirely inventions designed to support Evans's wishful beliefs in the nature of this early civilization. The same is true for some statuettes supposedly discovered in the ground, but really created at his direction to tell his story. In some cases he seemed to openly hint at what was really going on. The following has some examples out of a large collection of near-admissions he put in his massive multi-volume description of the site.

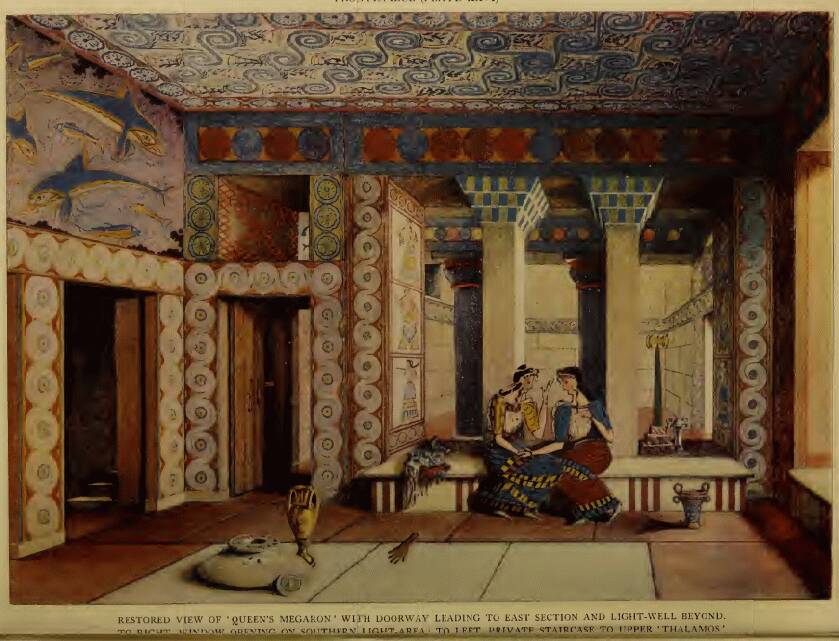

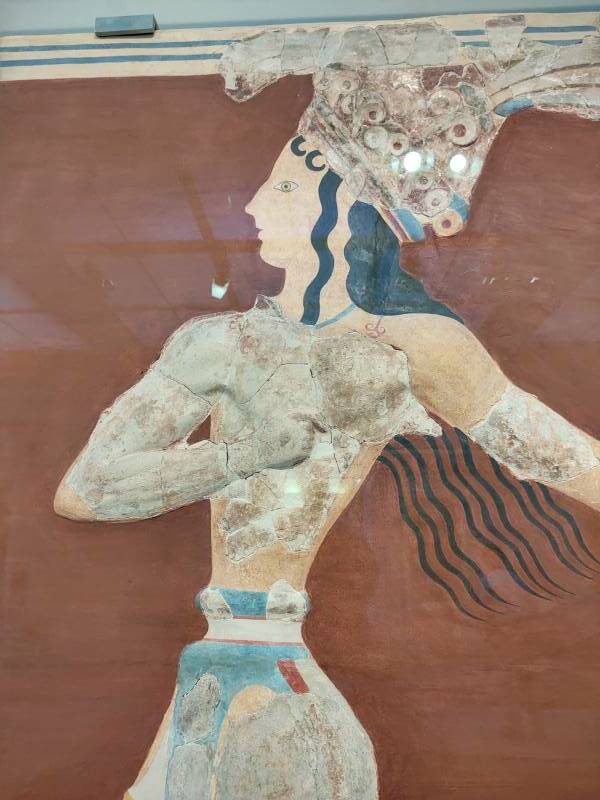

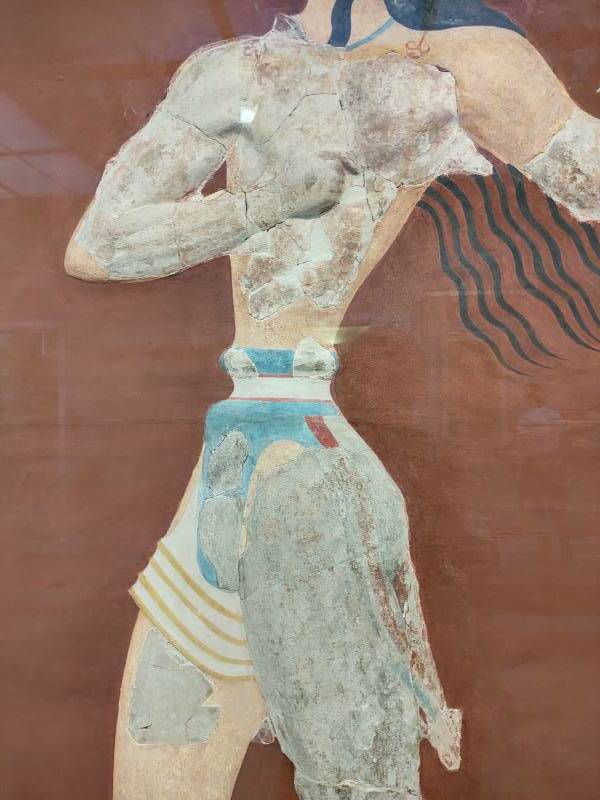

The frescoes at Knossos were very fragmentary. For most of them, almost all of what you see today are imaginative "reconstructions" or really de novo creations by Evans and his staff. Evans had a father-and-son team of identically named Swiss artists, Émile Gilliéron pers et fils, recreate the frescoes guided by his suggestions.

This "restored view" depicts frescoes and other decoration on the walls and ceilings, along with clothing, which were all dreamed up by Evans and painted by the Gilliérons.

From page 8 of The Palace of Minos at Knossos, Vol III, 1930.

Sir Arthur John Evans

Arthur Evans studied at Oxford, getting involved along with his brother Lewis in various international intrigues and adventures.

Visiting Bucovina in the CarpathiansIn 1872 the Evans brothers went into Ottoman territory in the Carpathians, crossing borders illegally in the mountains with "revolvers at the ready" as they wrote about it in Fraser's Magazine. The next year they went through Lapland, Finland, and Sweden. The year after that, Evans graduated from Oxford, barely. He had extensive knowledge in areas of ancient history and archaeology that interested him, but was unable or just unwilling to answer any of his examiners' questions on topics after the 12th century.

In the summer of 1874 he attended, or at least started, a summer term at the University of Göttingen. It may have been intended as a remedial session to make up for his lack of modern history knowledge.

Evans was quickly bored with Göttingen, and met his brother for another trip to the Ottoman-ruled Sanjak of Herzegovina. It was then in a state of violent insurrection that the Ottomans were trying to quell with Bashi-bazouks, notoriously cruel irregular soldiers from all over the Ottoman Empire. Arthur and Lewis planned to spy against the Principality of Montenegro at the resistance's strongest point in the mountain ranges of Ljubišnja and the Tara river gorge, the deepest canyon in Europe.

They got along fine with the Ottomans and the Serbs, but they provoked the Austro-Hungarian Empire's officers into imprisoning them for a night. They were eventually escorted to a British consulate just before the area erupted into mutual massacres of civilian populations. The Chargé d'Affaires was Evans's former mentor at Oxford, who had been quite tolerant of his lack of recent historical knowledge. But now Evans was embedded in current events. Extra credit for practical experience, maybe.

Arthur wrote about all this in Through Bosnia and Herzegovina, in two editions in 1876 and 1877. He was suddenly seen as an expert on the Balkans, and was sent back as a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian.

He married a daughter of the British consul to whom he had been delivered, his former Oxford mentor, and continued as a foreign correspondent. Eventually his continued support of native government if possible and local insurrection if not got him arrested, imprisoned for six weeks, then put on trial as a British agent provocateur. He and his wife were expelled from the country.

Evans and his wife moved back to Oxford in 1883. He finished writing some articles and decided not to apply for a new Professorship of Classical Archaeology.

Visiting Tiryns Visiting MycenaeInstead, he and his wife traveled to Greece to meet with Heinrich Schliemann, who had discovered Mycenae and excavated it and Tiryns.

Schliemann was similar to Evans — a huge fan of Homer, he concluded that obviously the Iliad and Odyssey must be literally true, so let's go find Troy. Which he did, sort of. He excavated the tell at Hisarlık near the Dardanelles in today's northwestern Turkey.

Troy has been interpreted as having nine distinct layers or strata. Troy I, the oldest at 3000–2550 BCE, is at the bottom, and Troy IX, from 85 BCE to 500 CE, is on top. Plus a recently recognized "Troy 0" from the Late Neolithic of about 3600–3500 BCE below all that.

Schliemann dug straight down to what he labeled as the Troy of Homer's description. However, whatever the Trojan War really was happened around 1250 BCE, with remains at the level of Troy VI and VIIa. Schliemann had quickly excavated all the way down to Troy II, from 2500–2300 BCE, four or five strata too far and slightly over a millennium too early. Any signs of King Priam and Achilles the warrior that Schliemann uncovered were tossed aside to dig much deeper.

And then, having quickly found, excavated, and interpreted Troy, Schliemann went to find Agamemmnon's tomb at Mycenae. He did the same thing, digging down through the stratum of Agamemmnon around 1250 BCE to discover much earlier shaft graves from 1600–1450 BCE, and then label one of them as obviously being Agamemmnon's.

Returning to Oxford, Evans found that the university's Ashmolean Museum was in a mess. It had been a natural history museum, but its collections had been transferred to other museums, leaving only some art and archaeology. The university planned to make those its focus and reorganize and expand the museum. Evans became Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford.

In 1892 and 1893, first Evans's father-in-law traveled to Spain for the beneficial climate but immediately contracted smallpox and died. Then Evans's wife died of tuberculosis. And then Evans began searching Athens markets for seal stones bearing mysterious writing, said to come from Crete. Here are some examples in the Archaeology Museum in Heraklion, seals with the so-called Archanes Script from around 1900 BCE.

In 1894 Evans was back in Crete. Archaeologists were waiting for the death of the "sick man of Europe", the Ottoman Empire. The Cretans were afraid that the Ottomans would take any discovered antiquities to the imperial museum at İstanbul. The Ottomans were stalling, trying to prevent any progress.

By now it was understood that a double axe head or labrys was a symbolic item for some Aegean civilization probably predating the Greeks. An actual double axe was a weapon, but there were also purely symbolic versions, some of them small to be worn or carried as amulets.

There were also bronze daggers and swords that were symbolic copies of actual weapons.

These ritual swords and daggers found in Crete have no real tangs for grips, so they weren't useful in battle. They served in some ritual role.

This full-sized bronze double axe head dating to 1700–1450 BCE was found at the Arkalochori cave on Crete. It has three columns of inscriptions along the central socket. Some of the signs resemble Linear A, while others are similar to signs on the Phaistos Disc.

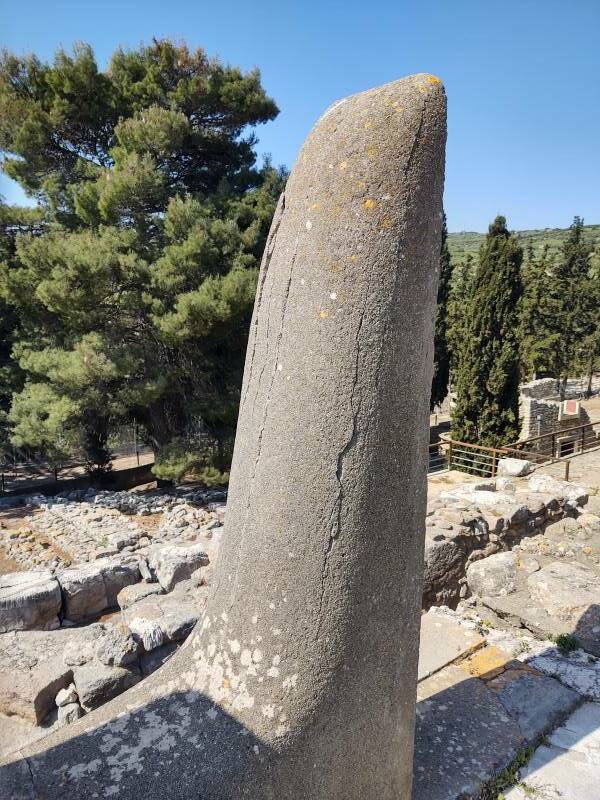

Evans went to Knossos. The initial excavations by Minos Kalokairinos had exposed a wall bearing the sign of the double axe head. Evans concluded that this site must be the source of the mysterious script he had seen on seal stones. The Mycenaean Greeks and, it seemed, this earlier civilization, used it as an apotropaic mark preventing an object's destruction or misuse. The mark of the double axe on a wall would protect the building.

The Ottomans disallowed property purchases by foreign individuals, but allowed purchases by funds. The Cretan Exploration Fund, to which Evans was the only contributor, bought a quarter of the Knossos site with first option to purchase the rest later.

Evans Loses His Military Enthusiasm

Beginning with his Balkan adventures with his brother, Evans was quite enthusiastic for intrigue and revolution. In 1895 he and his friend John Myres explored the Lasithi plain of eastern Crete documenting a Bronze Age network of fortresses and military roads in the area. They listed cities with defensive walls, fortifications against enemies, with forts, bastions, and watchtowers. They described them as being of "Mycenaean times" as Evans had not yet invented the term "Minoan".

The Greek War of Independence had lasted from 1821 to 1829. Greece at large became independent. Crete, despite its involvement and suffering, remained in Ottoman control. There were several large revolts in Crete during the 1800s, with those in 1841, 1858, 1866–1869, 1878, and 1889 just being the most prominent.

The Cretan Revolt of 1897-1898 finally forced the end of direct Ottoman control. The last Turkish troops left Crete in 1898 and the violent reprisals started. Cretan Christians began massacring Turks, and Turks tried to defend themselves. The British government, part of the "Great Powers" administering the Ottoman departure and Cretan transition to independence, forbade travel by private citizens, but Evans stayed on in his old role as correspondent for the Manchester Guardian.

By 1899 a new constitution had been written, a government of both Christians and Moslems was established, and Crete was a republic. And, Arthur Evans was now a pacifist. The Cretan Revolt of 1897-1898 and the following reprisals in 1899 were the end of his enthusiasm for military adventures and warfare.

Evans was sickened by the violence and had come to believe that the earlier society must have been a pacifist one. He believed that it had been ruled by a matriarchy and it worshiped a Mother Goddess, with its only weapons being ritual ones used in ceremonies that took the place of violent conflict. The sacred dance of Ariadne, the Boy-God worshiped along with the Mother Goddess, various purifying rituals, Evans convinced himself that all of these must have been real. Now he had to find them.

This is not how to do science.

If This is the Palace of Minos, Then These Must be the Minoans

Once the Ottomans departed, the other archaeologists discovered that Evans, through his one-person fund, had purchased the rest of the two-hectare site of Knossos.

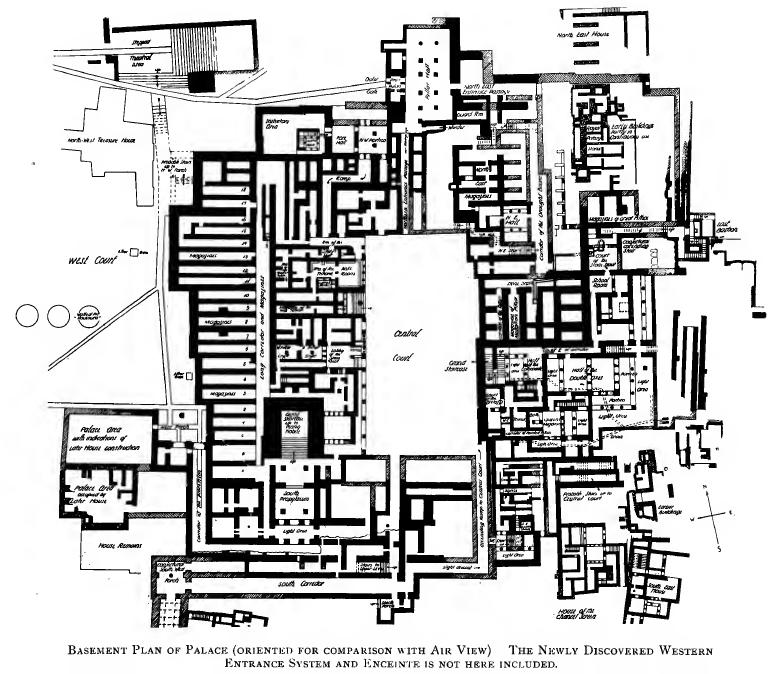

Arthur Evans began his excavations at Knossos in March 1900. Within a few months they realized that they were uncovering an intricately interconnected three-dimensional network of over 1,000 rooms. There were at least three to four levels through most of the complex.

Evans called this overall complex a "palace", although some of it was artisans' workshops, food processing spaces, and religious and, presumably, administrative spaces.

The initial excavation continued through 1903. Evans and his team kept working here through 1935.

Arthur Evans's four volume report, The Palace of Minos at Knossos, was completed in 1936. Research and conservation continue today.

Sir Arthur Evans

Vol I, 1921 Vol II, Pt I, 1928 Vol II, Pt II, 1928 Vol III, 1930 Vol IV, Pt I 1935 Vol IV, Pt II 1935 Index, 1936

Based on ceramic styles, failing to match them to anything known from Greece but finding apparent parallels to pieces from the Levant and Egypt, Evans concluded that this civilization on Crete had existed before the Mycenaeans. That turned out to be true.

When I was little, my parents would leave me with my grandmother while they went off and did whatever grownups do. I had a set of Lincoln Logs1 that I kept at her house. I also had the Lincoln Logs that had belonged to one or both uncles who had grown up in that house. They were slightly rectangular rather than round in cross-section but they had the same dimensions and fit together with the new ones. I could get into some really complicated and impractical designs with the merged sets. Internal air shafts and seemingly pointless connections, like at Knossos. Now I see that I could have called them my "Minoan structures".

The maze-like quality made Evans think of the Labyrinth of Greek myth. He should have seen my Lincoln Log projects.

Homer had described Minos as the king of Knossos on Crete in his Iliad and Odyssey. The myths tells us that Minos' wife Pasiphaë was more than just bovine-curious, she had a definite thing for bulls. A sexual thing. It had something to do with Minos once failing to sacrifice an especially fine bull to Poseidon, leading to Poseidon cursing Minos by giving his wife this weird obsession.

Pasiphaë had Daedalus, the king's dangerously imaginative inventor, build her a wooden cow that she could hide within. A bull would mate with this apparent cow, and really be mating with Pasiphaë.2 Ouch.

2: Even if you discount all the times that it was really Zeus in disguise, Greek myth features a lot of zoophila, to use a Greek-derived term.

The bull impregnated Pasiphaë and the hideous result was the half-man half-bull Minotaur. Minos didn't want people to know the Minotaur's origins or even of its existence, and can you blame him? So, he had Daedalus devise a complicated underground maze. He then locked the monstrous Minotaur, and Daedalus, and his son Icarus inside it. Daedalus and Icarus escaped, of course, using yet another dangerous invention of Daedalus.

Evans concluded that obviously the Knossos complex was the palace of King Minos. And therefore the people who built and occupied it must be the Minoans.

From page 33 of Volume IV of The Palace of Minos at Knossos

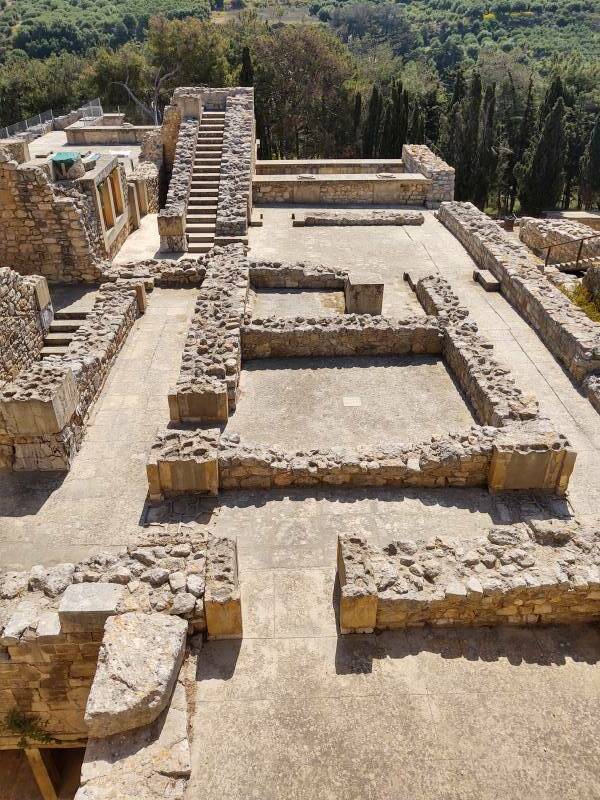

You enter the Knossos site past the Kouloures storage facilities, at center left on the diagram above. One viewpoint is that "Storage is about controlling the future, and thus authority."

The Western Magazines are another large communal storage area.

Once inside you pass several restored pithoi or clay storage vessels.

What About Their Language?

The reality is that we have no idea what these people called themselves. Nor do we know anything about what their language was like. As explained above, the inhabitants of Minoan times likely crossed the Mediterranean from Anatolia, where some Indo-European languages were spoken. But we have no evidence that their language was at all like any of the known Anatolian languages.

Ancient Yersinia pestis and Salmonella enterica genomes from Bronze Age CreteWe now know that their civilization began around 3500 BCE, with a complex urban civilization beginning around 2000 BCE, then declining from about 1450 BCE until its end and replacement by Mycenaean Greece around 1100 BCE. See the explanation of the broad collapse of Bronze Age society in 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed.

3-D data collection and analysis of cuneiform tablets from Ur

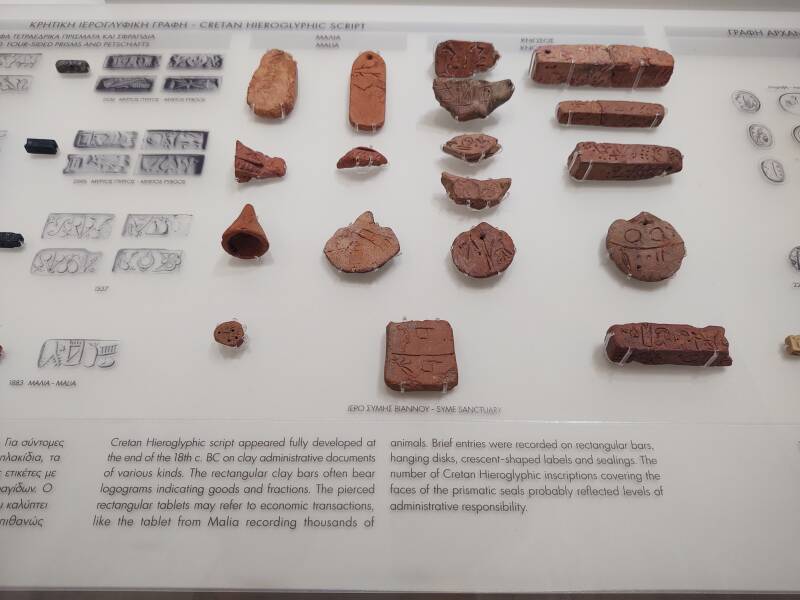

Evans figured out that the mysterious seal stones and other

transcriptions were in three scripts, which he named as

Minoan hieroglyphics,

Linear A,

and

Linear B.

Two of the scripts are named "Linear" because they were

written by cutting lines into the clay with a stylus.

Cuneiform, on the other hand, was written by pressing

wedge-shaped depressions with a stylus.

There are Unicode definitions for Linear A and Linear B,

in addition to cuneiform.

This page demonstrates that Linear B can be used within HTML,

but it's up to your browser to display it properly.

KO-NO-SO or

𐀒𐀜𐀰

is

𐀒𐀜𐀰

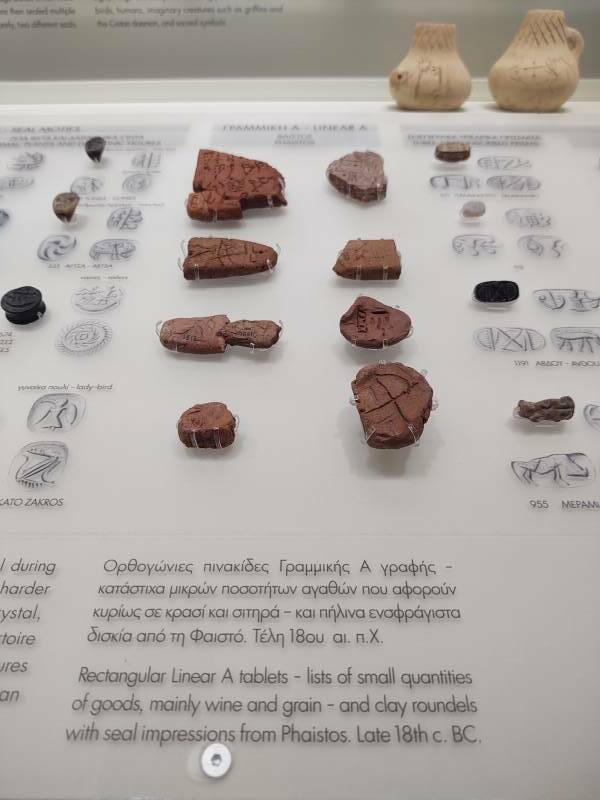

Clay tablets with Cretan Hieroglyphic Script from late 18th century BCE in the Archaeology Museum in Heraklion.

These tablets have Linear A, which is still undeciphered, beyond the signs for numbers. We interpret from their discovery contexts that some seem to list inventories of grain or other items.

We have 1,427 specimens of Linear A containing 7,362 to 7,396 signs, written on various media. They were found mostly on Crete, with some from the Aegean islands of Kea, Kythera, Melos, and Thera, and a few from Laconia on the mainland. One researcher has observed that in a standard typeface the complete Linear A corpus would fit onto two pages.

Arthur Evans had a strong Classics education gave him some wild ideas about the possible relations of these scripts to Phoenician and other languages of the Levant, to Anatolian languages, and others. Alice Kober did a lot of analysis through the 1930s and 1940s discovering the statistical and linguistic characteristics of Linear B. Then in 1952 Michael Ventris showed that Linear B was used to write Mycenaean Greek.

Linear B has been found on tablets from Crete and the mainland. Ventris noticed that some strings only appeared on tablets found on Crete, and suspected that they were place names in Crete. And, some Mycenaean Greek names of some places on Crete were already known from other sources. This was the crucial insight for deciphering Linear B. Here are some tablets with Linear B place names.

Now historians could read labor, agricultural, and business records of this time and place. Plus some limited religious texts.

And so, some descriptions of the society that left these records.

Historians want to find a society's stories of its history, of its religious beliefs and practices, and otherwise of what it was like to live in that place and time.

Linear B was derived from Linear A. Now that scholars knew how to read Linear B, it was obvious to try pronouncing Linear A texts by using the sounds of the corresponding Linear B signs. The result of such a "reading" of Linear A doesn't resemble any currently known language.

So yes, the Linear A script was modified or evolved into the Linear B script. But the two seem to have encoded entirely different languages.

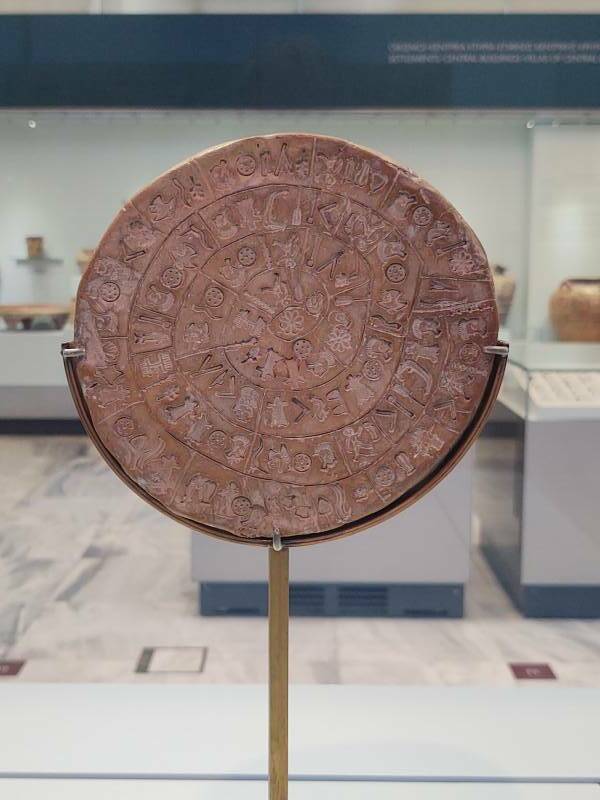

The remaining complete mystery is the Phaistos Disc, found at the Minoan complex at Phaistos in southern Crete. It's a two-sided disc about 15 cm in diameter and a little over 1 cm thick. It has been dated to between 1850 and 1600 BCE based on its being found in an undisturbed context.

It is the only known sample of its hieroglyph-like writing system. The two sides of the disc contain 241 signs drawn from a set of 45. The signs were impressed upon the disc by being pressed with seals. It is not "the earliest form of printing" as sometimes said, it's sign-by-sign stamping. An inscribed spiral guides the sequence of signs, and short vertical lines divide signs into presumed words of two to seven signs each.

The numbers of sign forms and signs used indicate that it almost certainly is a syllabary. But it's such a small sample of the language that there's no hope of deciphering any of it unless we discover more example texts.

Infrastructure

I am aDrainfluencer

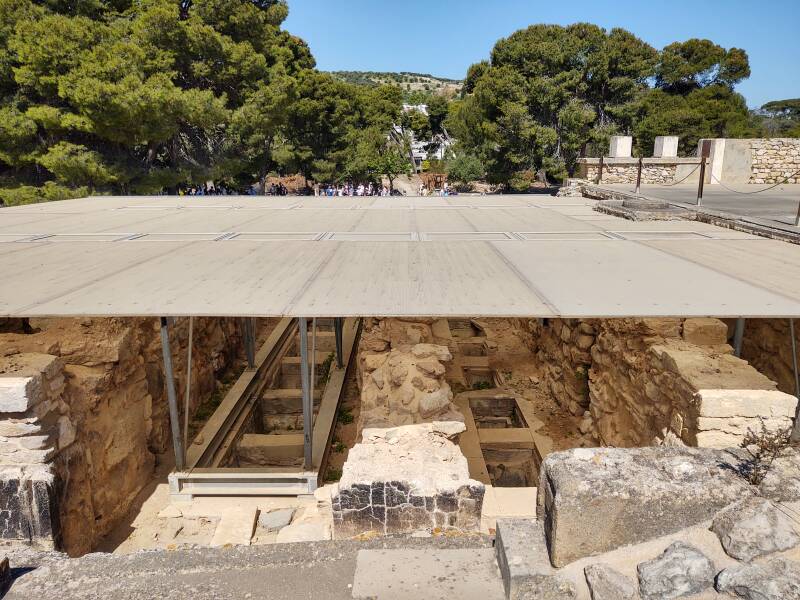

The famous drain lines of Knossos are some of the first things you see as you enter the site. That is, if you're observant and know what to look for and how to interpret it. Look! Drains!

Knossos had separate wastewater and storm drains. That is, independent sewer lines and storm water drains.

Many cities in today's United States don't have this. In those cases, all septic wastewater and relatively clean rainwater runoff go into a unified drain system. This means that raw or at least incompletely treated sewage is dumped into streams during periods of heavy rain.

West Lafayette, where I live, is home to a major university with programs in both sanitary engineering and public health. In 2022 the city was still working to finish its conversion to separate wastewater and storm drains.

Knossos had solved this problem before 1450 BCE by using drains like the above.

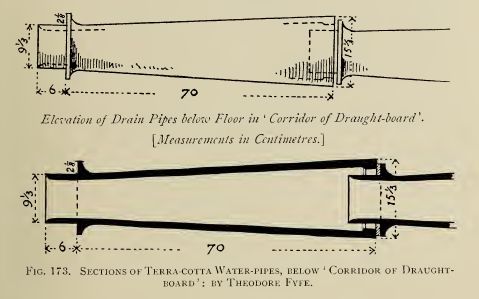

Knossos famously had tapered clay pipes supplying fresh water. Here is an example.

Here's how they worked:

Figure 173, page 253, The Palace of Minos at Knossos: Volume III.

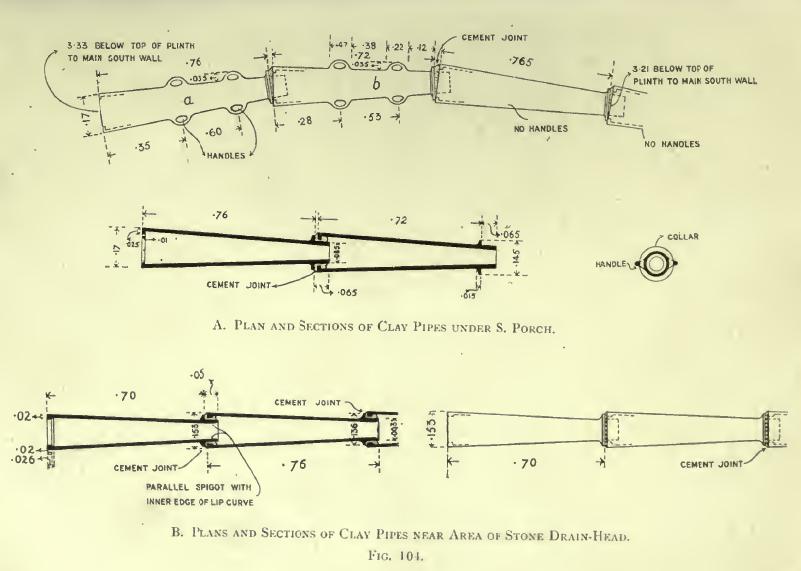

Figure 104, page 143, The Palace of Minos at Knossos: Volume I.

The drain systems flowed into the valley to the east of the city.

And then there was the so-called Queen's Toilet. The attribution is due to Evans's late 1800s sensitivities about what would be the King's versus the Queen's rooms in a palace, complicated by his fixation on this being a matriarchal situation.

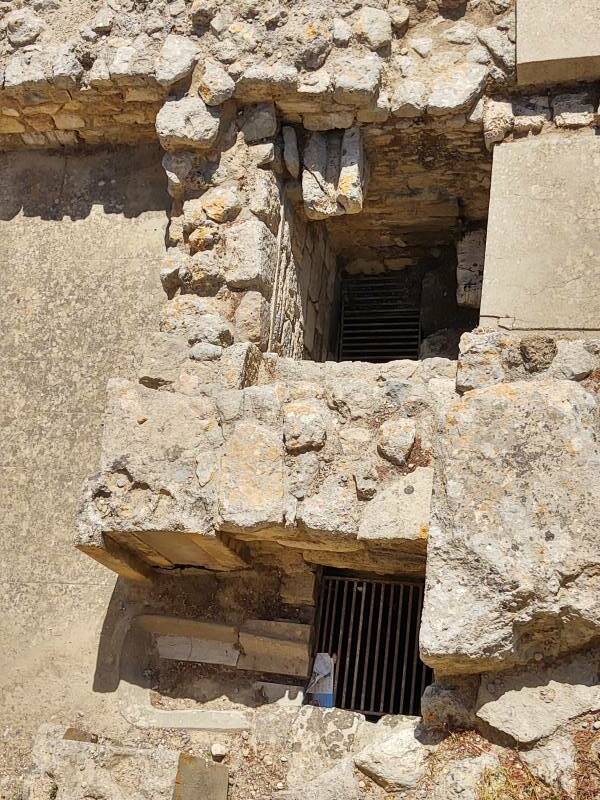

We're looking down from the Central Court. The Queen's Toilet is at bottom center of this picture. There's a dark open shaft with a rainwater drain feeding into it near the center of this image. The Queen's Toilet is below it.

Here's a view from a slightly different angle.

And a view zoomed in somewhat. The idea is that there was a wooden seat over the shaft now covered with a metal grill. There would have been a door closing off the space. The Queen could then call for a servant to pour water into the horse-collar-shaped trough running left-right in these pictures. This makes it one of the first known flushing toilets in the world.

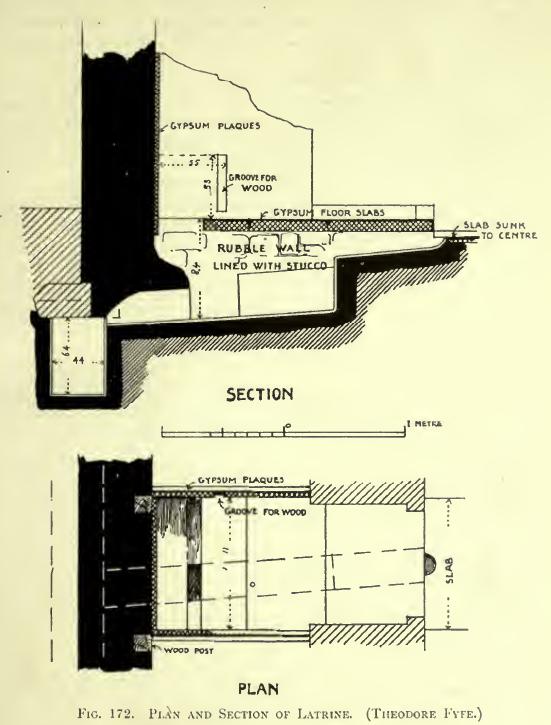

Figure 172, page 229, The Palace of Minos at Knossos: Volume I.

Toilets

Above are cross-section and plan views of what Evans and his excavators discovered at Knossos.

For far more on Minoan plumbing see the descriptions and diagrams at the Toilets of the World site.

The Queen's Toilet is along the wall along the right side of this view, at the far corner of the uncovered area.

The Steel-Reinforced Concrete

Evans discovered and described the water pipes and drains and toilets in precisely their original forms. (Although his reconstruction moved the Queen's Toilet from the east to the south wall of that chamber, disconnecting it from its original drain which was destroyed in the excavations)

However, all of the steel-reinforced concrete that he installed was a new development at Knossos.

Along the Path of the Andartes' Abduction of General KreipeHe had commissioned Villa Ariadne, a colonial British home suited for the colonial overseer of a project like this. Very early in its construction he saw the new technology of ferro-concrete, concrete poured into wooden forms containing reinforcing steel rods and mesh. This rapid method of building sturdy structures struck him as a desirable way to reconstruct what he imagined Knossos to have been. The villa was nice, the occupying Nazi German forces seized it for their commander's home during World War II.

You see the ferro-concrete result almost as soon as you enter the site. If you look at it with a practical eye and no idea of what Evans was up to, it looks quite strange.

As described in Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism, this isn't at all the form of Knossos back in the mid-second century BCE. Nor does it attempt to be a complete reconstruction of what it might have been.

This is a modernist artistic partial depiction of what it could have been. Walls, floors, and horizontal beams terminate in conceptual "and it would have continued thusly" breaks.

It makes no sense if you try to take it literally. Instead, it's a modernist sketch implemented in concrete. Squint and it makes sense.

There are recreations of frescoes. But whatever was here didn't look exactly like this. These aren't restorations of ancient frescoes.

These are early 20th century creations of what Evans thought they should have looked like.

The Archaeology Museum in Heraklion has a "restored fresco" of three women from Knossos. But as you can see here, it's almost entirely invented. The women's faces and hair, all but a small part of one hand, and almost all of their clothing and jewelry were dreamed up in Evans's artists' workshops.

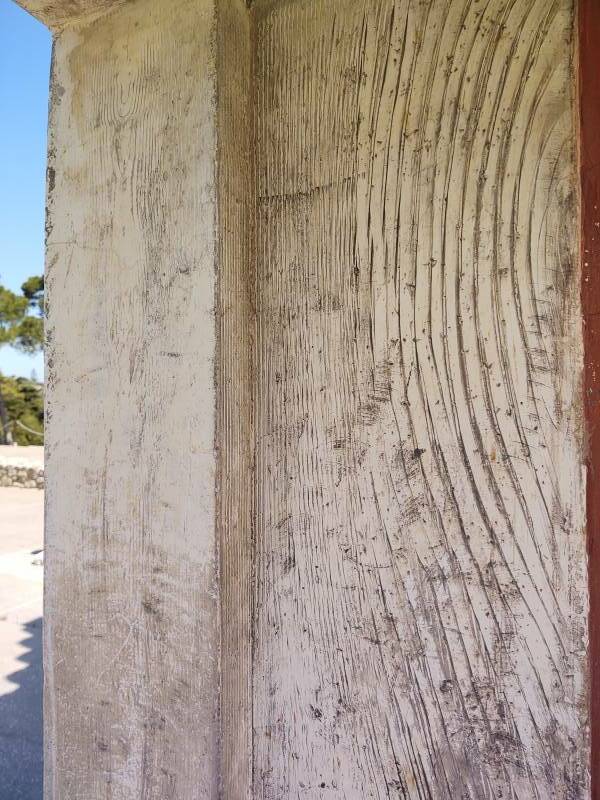

The "broken ends" of horizontal beams are cleverly formed. This looks as though a horizontal beam was broken off. But instead this is all there ever was. And notice how the concrete beams have a wood grain pattern.

The wood grain pattern is made with both a physical texture and two shades of paint.

These reinforced concrete "reconstructions" or "reconstitutions" date from the early 20th century. That leads to meta-level curation problems.

They aren't at all original, they don't include any cut stones or column pieces or capitals made by the inhabitants of the second millennium BCE.

They are historic in their own way, documenting the work done here and also the development of modernist design or at least modernist interpretation and re-interpretation. So, how should we repair and preserve what Evans built? It's a significant part of art history.

The above "staircase to nowhere" ends with what looks like either new or newly painted or coated reinforcing rods. The below image cropped from my original shows light blue coating or paint on the steel.

Bulls and Horns

The people living here involved bulls in some beliefs and practices. They certainly had many small figures of them. As we will see later, they had a "Bull Leaping" activity.

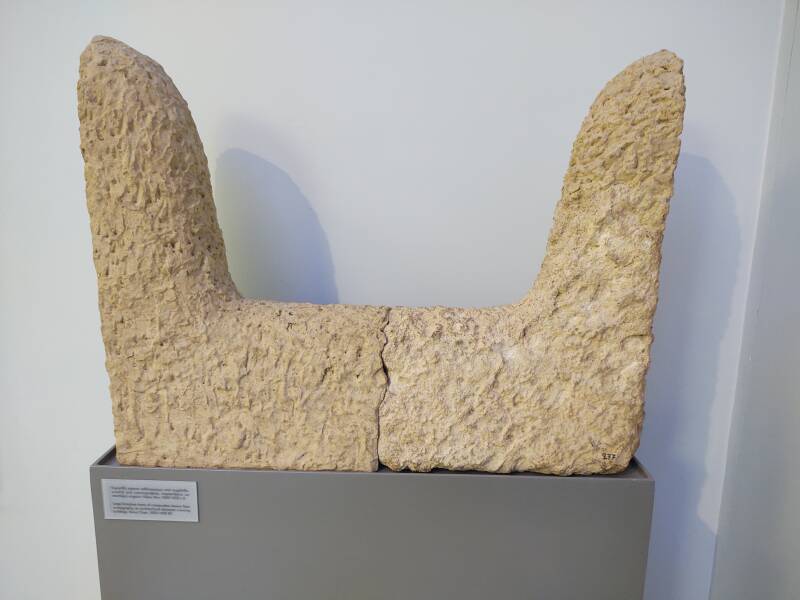

The bull imagery seems to have led to what Evans described as Horns of Consecration. Exactly what was consecrated at one of these, or how, remains a mystery. But they have been found at multiple Minoan-era sites around Crete and by researchers other than Evans. The museum in Heraklion has an example from Νίρου Χάνι or Nirou Chani from 1500–1450 BCE. It is made from limestone and is in pretty good shape for being at least 3,450 years old.

The museum also has a wooden model of the palace as Evans imagined it looking at its peak. Several of the structures are lined with Horns of Consecration. But there is no evidence that there were anywhere near this many at any site. Nor is there evidence that they lined rooftops.

The Knossos site has an Evans-era "Horns of Consecration" made mostly of reinforced concrete with a relatively small limestone component.

But once again the early 20th century reinforced concrete is breaking down. What is the intellectually honest solution?

Lustral Basins

Evans's team found several examples of a sunken rectangular space accessed by an L-shaped or multi-turn stairway. Many had a balustrade alongside the stairway, ending with a pilaster supporting a column.

Whatever these were, they existed in Minoan sites across Crete, including those not discovered until after Evans's work at Knossos.

Evans believed that these spaces were used for ritual bathing, or purification through lustration, and so he called them lustral basins. Here's a mostly reconstructed example at Knossos:

This is what Evans labeled the North Lustral Basin. He believed that the entire Palace complex was a sacred site, and therefore visitors entering it along the common direction, from the north and the direction of the port, would need to purify themselves before entering.

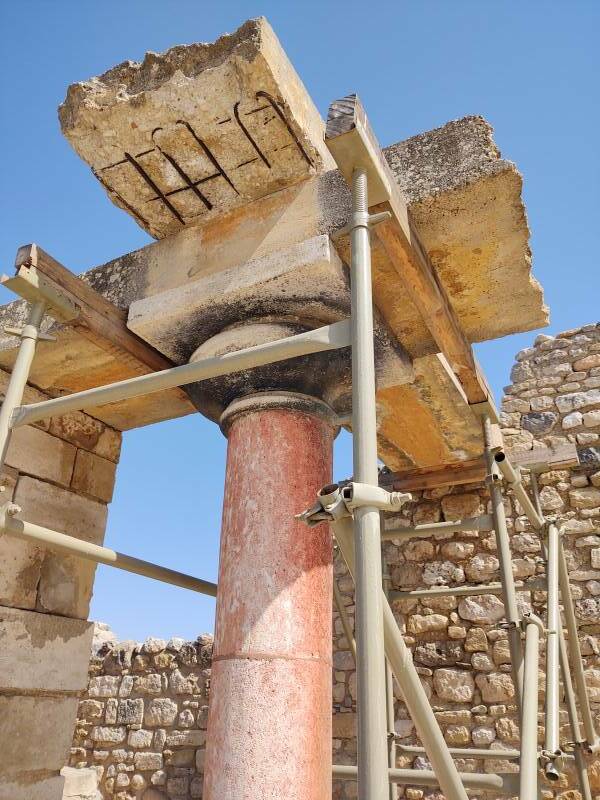

You'll notice that Minoan columns have an "upside-down" taper, wider at the top than the bottom. This seems to be something Evans saw not in a physical example but depicted in one very fragmentary fresco. He liked the way it looked, and so all of his re-creations got reverse-tapered columns. Then that could be picked up in other modernist designs. Frank Lloyd Wright, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Kenzō Tange, Alvar Aalto, and other prominent Modernist architects might have thought that they were borrowing from the first European civilization, but they were really borrowing from Evans.

A major problem is that all of the lustral basin examples at Knossos, and many of those at other Minoan sites across Crete, are lined with gypsum. That's a water soluble mineral, a very poor material for lining a bathing chamber. It's the main component of blackboard chalk, drywall (or sheet rock or gypsum board), and many forms of plaster. It's useful for those applications, but it's not at all good for lining a water tub or tank. Frank Lloyd Wright's designs were notoriously impractical, but even he would probably hesitate to line a water tank with gypsum sheets.

Another glaring problem is that none of the lustral basins have drains. The Knossos complex and others in Crete are famous for their surprisingly advanced plumbing, both water supplies and drains. The lack of plumbing at these so-called lustral basins indicates that these weren't filled with water. The Minoans knew how to do that right. These weren't Minoan water tanks or tubs.

Many lustral basins throughout Crete and at the Cycladic but Minoan-influenced Akrotiri site on Thera were found to contain cult objects. They might have contained offering tables or sacred vessels. Or the walls might have been decorated with religious themes. These structures could have to do with a chthonic or underworld deity associated with the renewal of nature. Many current scholars prefer the term Adyton for these spaces, a Greek term meaning "off limits", referring to the most holy part of a temple of Classical Greek times.

4: "Ritual performances in Minoan lustral basins: new observations on an old hypothesis", in Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Oriente, vol XC serie III, 12 2012.

Dario Puglisi's paper4 points out that the frescoes in the Xesté 3 lustral basin at the heavily Minoan-influenced Akrotiri site on Thera depict a female rite of passage. So, this might have also been their use in sites in Crete.

Meanwhile, "Lustral Basin" should probably be rendered exclusively in so-called "quotation marks".

The Throne Room

Another problematic "lustral basin" is in what Evans called the Throne Room at Knossos. There will be a line. It stretched all the way across the Central Court both times I was there during "shoulder season", mid-April through May and September through mid-October. I also found that I often simply had to wait while a large group with a guide completely blocked an area I wanted to see. A visit during high season would be extremely frustrating. But then most everything else about visiting Greece is much better during the shoulder season.

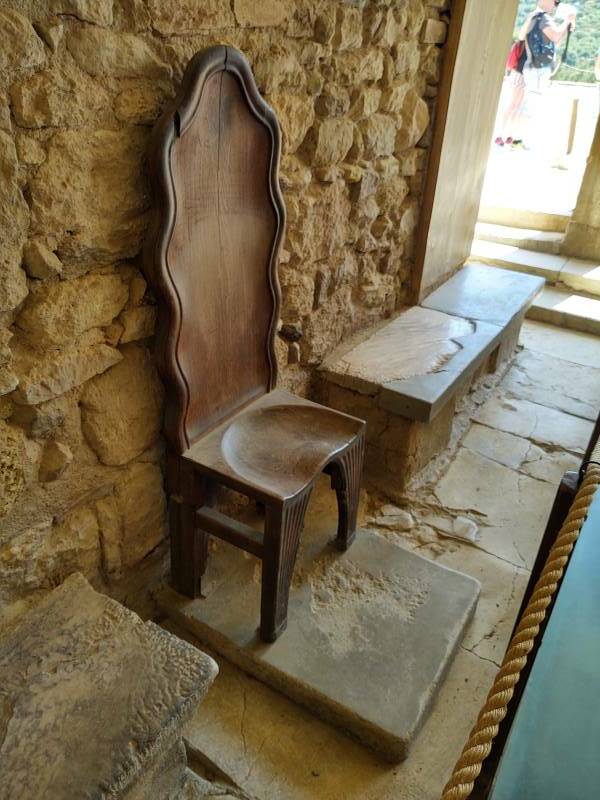

You initially enter an outer chamber with a wooden throne chair. Then you can move to the rear and look over the transparent barriers into the Throne Room.

It's not a very grand throne room for such an impressive complex. Yes, there is an alabaster chair along one wall, with gypsum benches for some henchmen to either side. But is this the throne room of an empire that participated in trade all around the eastern Mediterranean and inland to Mesopotamia and beyond at its peak?

There's a large bowl which Evans and the descriptive material at the site both admit was found somewhere else and brought here because, well, it looked nice here.

Evans's multi-volume report describes the frescoes, and goes into the meaning of the griffins and how they were designed. But he is describing how he designed them. The museum in Heraklion has the best surviving fragments of original frescoes from this room, showing that what you see today is Evans's creation:

Steps descend to the gypsum-lined "Lustral Basin".

The supposed throne looks across the small room to the "lustral basin". Did the ruler simply sit there and watch a ritual? Or did the ruler cross the room and enter the "lustral basin"? And if so, what happened there? No one has any idea.

Then you pass the wooden throne chair on your way back out. Evans's restorers found just some carbonized wood here, hypothesized that maybe there had been a wooden seat shaped like the alabaster "throne", and made this replica.

Here we're looking across the north end of the Central Court to the three-level Throne room complex. The four doorways beyond the line of people lead into the Throne Room, and notice that there are two levels above that.

However, compare the above view to the below picture from Evans's report on the excavations. The text says that the ground level when the excavations began was slightly above the top of the wall you see at right here. There is the throne, now exposed to daylight. The walls of the Throne Room only extended up to about shoulder height. The two stories above it are entirely inventions by Evans.

So is the modernist design.

It resembles a small Finnish rail station, or Lenin's Mausoleum. Or something similarly from the early Modernist Architecture movement.

Minoan Religion

The dominant figure of Minoan religion was a goddess. She was often associated with a younger male figure, perhaps a consort, perhaps a son, or perhaps both.

It seems that priestesses served the goddess. We can't be certain of what any images or figurines represent, because the priestesses may have performed as the goddess in rituals. Are we seeing the goddess, or a priestess imitating the goddess?

A painted stone sarcophagus from Hagia Triada around 1400 BCE is believed to depict the funeral of an important man. The most important figures leading the ritual are women, with men limited to carrying offerings and playing music.

In a similar way, we also can't be sure whether an image represents a deity or a ruler, and maybe the ruler was considered to actually be a deity, or maybe the ruler performed in the role of the deity in rituals. Maybe the ruler was the top priestess or priest and performed as the deity in rituals. Crete had trade connections with Egypt and Mesopotamia, where the rulers were thought to be related to the gods.

We have no written description of their beliefs, we don't even know the names of the deities.

Archaeologists have identified a mountain goddess associated with sanctuaries on peaks, a snake goddess who may have been a household protector, a dove goddess, a goddess of animals in general, and a goddess of childbirth.

Beginning in the 1980s, evidence was found at three Minoan sites strongly suggesting the practice of human sacrifice well before the arrival of the Mycenaeans.

At Knossos, archaeologists discovered the bones of at least four children who seem to have been in good health when they died. The bones had cut marks similar to those made by the Minoans when butchering their sheep and goats. This suggests that they were sacrificed and possibly eaten.

The Snake Goddess Dethroned: Deconstructing the Work and Legacy of Sir Arthur EvansBy the time Evans started excavating at Knossos, he was disillusioned by violent patriarchal societies. He dreamed of a prehistoric utopian civilization ruled by a matriarchy and worshiping a Mother Goddess. And at Knossos he set out to find it. He would misinterpret and simply invent details as needed to find the story he wanted. "Minoan civilization as it should have been." or something like that.

Evans and his restorers were creating a modern representation based on the art and architecture of their time. This included modern artifacts processed to look as if they had been buried for millennia, like these:

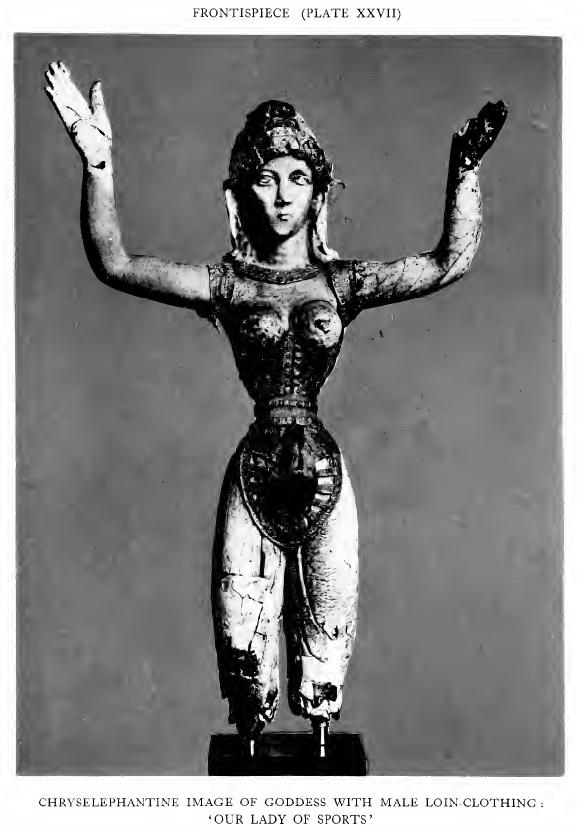

Chryselephantine (gold and ivory) goddess figurine, Plate XXVII (Frontispiece) of Volume IV of The Palace of Minos at Knossos

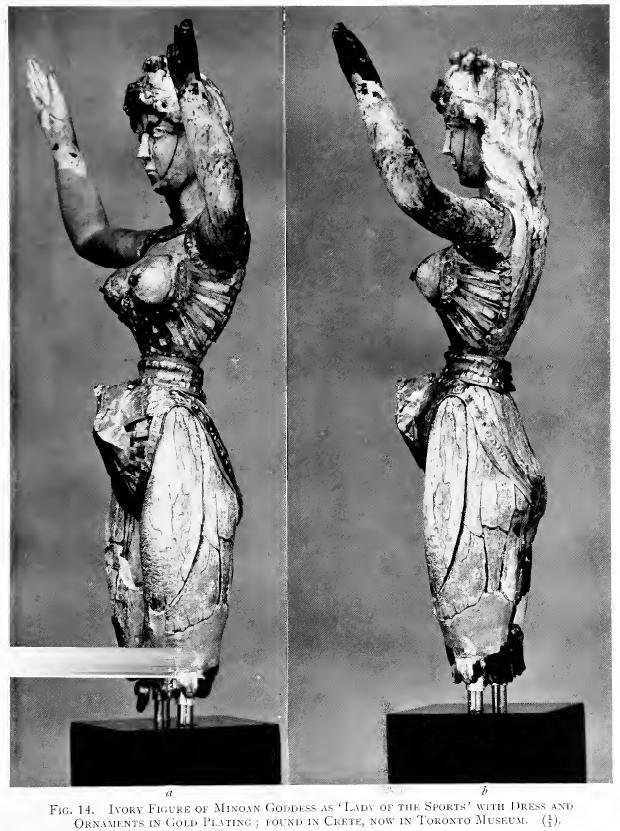

Chryselephantine (gold and ivory) goddess figurine, Figure 14 of Volume IV of The Palace of Minos at Knossos It was displayed in a Toronto museum, presumably the Art Gallery of Ontario. Museums have now mostly removed known forgeries from public display.

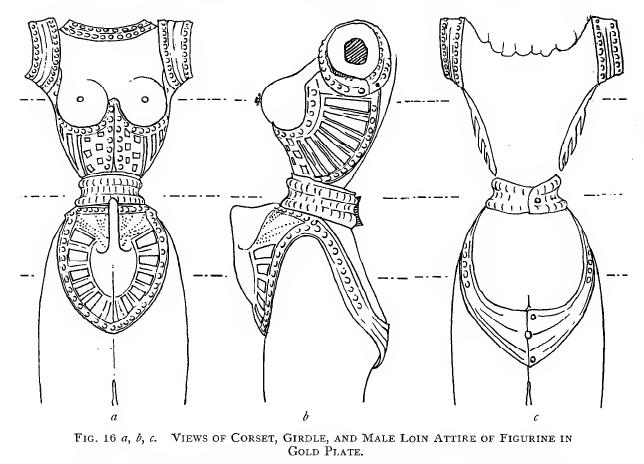

The codpiece or "loin-clothing" is very bizarre. It's the result of a series of inventions and willful misinterpretations that Evans made to support earlier "discoveries" of his idyllic matriarchal society.

Chryselephantine (gold and ivory) goddess figurine, Figure 16 of Volume IV of The Palace of Minos at Knossos

The "male loin attire" in the caption is called "the Libyan sheath" in the text. Other archaeologists used the term penistache for this odd bit of garb. Here's a short description from The Eastern Libyans, 1914, pg 112:

Bull-Leaping

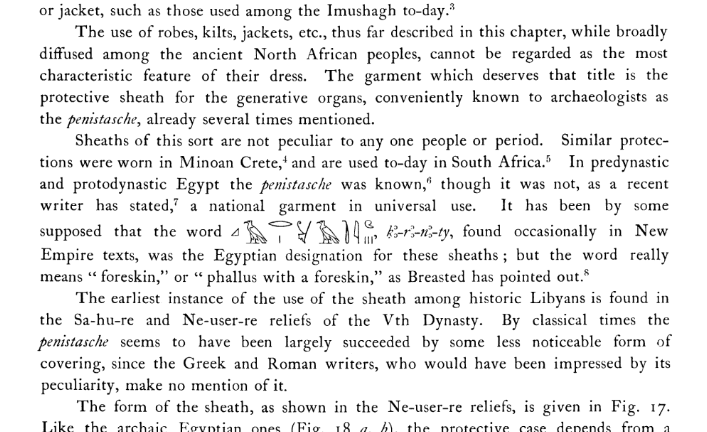

The bull-leaping ritual was depicted in frescoes, seals, and gold rings found at Knossos and other sites. Young people were shown vaulting over charging bulls. Here's an example of a heavily reconstructed fresco from Knossos in the Archaeology Museum in Heraklion.

Around 1477 BCE in Egypt, Pharaoh Thutmose III ordered the construction of a palace in the city of Pera-nefer in the Nile delta, at today's Tell el-Daba. He wanted it to have elaborate frescoes, so he brought in Minoan artists. They created bull-leaping scenes, quite the exotic touch for the Pharaoh's new palace. 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed describes how similar depictions of the activity then spread to sites in today's Israel, Syria, and Turkey.

But we don't know the purpose of the activity. Was it some sort of contest? A rite of passage?

Evans was set on portraying Minoan culture as matriarchal and entirely non-violent. He described the "bull-leaping" imagery as depicting ritual games that entirely took the place of warfare, and included the ruling matriarchy.

Evans had painted himself into a corner. Eastern Mediterranean art, including Minoan, generally depicts men with dark skin and women with light skin. In order to tell the story he wanted to tell, sometimes the women had to instead be men, and sometimes the men had to instead be women.

So Evans further stretched his descriptions of culture-wide androgynous appearance and even vaguely described "sexual transformation" as far as he needed to provide extremely sketchy support for his overall story.

Hence the cod-pieced women.

Here are two of the "Snake Goddess" figurines in the Heraklion museum.

These aren't sporting "Libyan sheathes" but they seem to be just as fake as the other purported archaeological finds manufactured in Evans's workshops.

The famed archaeologist Leonard Wooley's 1962 memoir As I Seem To Remember describes accompanying Evans and his primary assistant Duncan Mackenzie to visit a dying Knossos restorer. The artist made a literal deathbed confession that the restorers had for years been forging the supposed Minoan antiquities that Evans had been reporting as real. The archaeologists went to the workshop and found forgeries, frescoes and figurines, in various stages of production.

The area to the west of the Central Court includes what Evans called the Tripartite Shrine, seen below. There are small dark rooms back in here, he called two of them the Pillar Crypts. He said that near them were two large rectangular repositories carved into the stone floor, filled with clay vases and valuable objects including the "Snake Goddesses". He called these the Temple Repositories.

In the introduction to Volume III of The Palace of Minos at Knossos, on page viii, he boldly says that key pieces supporting his story were found not at Knossos, but in "the midst of doubtful elements" in antiquity dealers' shops. Then he goes on to conflate religious imagery from very different traditions. The "Boston Goddess" mentioned below used to be displayed in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Now it has been removed from public view and doesn't appear in their online search. Some other museums have kept items associated with Knossos on display while adding clear descriptions of their suspected forgery.

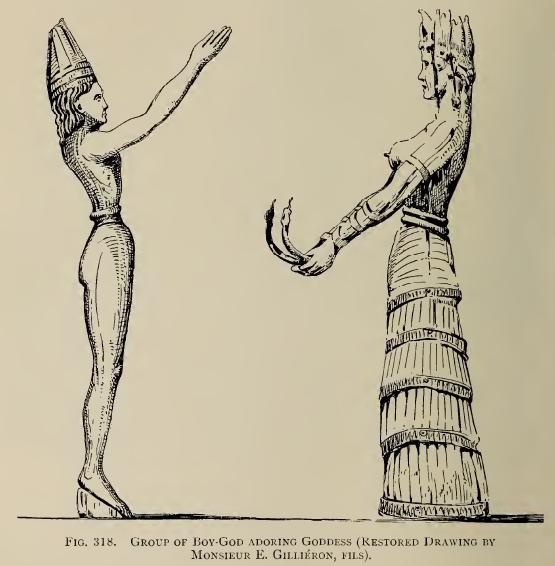

The remains of a small relief of an ivory Sphinx in the Minoan style, part of a miniature painting of a pillar shrine adorned with double axes, and two bronze axes themselves of the diminutive cult type, made it strange that no figure of the divinity itself should have occurred in the deposit. On the other hand, such an ivory figure, seen by a competent archaeologist in private hands at Candia [today's Heraklion], shortly afterwards emerged on the other side of the Atlantic as the 'Boston Goddess' — divine sister of the Lady of Knossos — holding out in this case golden snakes. The opinion, shared by our foreman and others, that this had been abstracted from the Ivory Deposit has certainly not lost in credibility from a remarkable sequel. Also emanating from private possession at Candia, but released after a further discreet interval of time, an ivory figure of a boy-God made its appearance. Having been successful in rescuing this from the midst of doubtful elements in a Parisian dealer's hands, it has been possible to ascertain the fact that it not only answers to the other in exquisite naturalistic style and individuality of expression, but, as shown standing on tiptoe and coifed with a high tiara, correspond within a millimetre or so in measurement. The two figures in fact form a single group of the divine Child God saluting the Mother Goddess.

An illustration of the Minoan worship of the Mother and Child had been already supplied by the painted clay figuring of a later date found in a tomb of the Mavro Spelio Cemetery at Knossos. It is supplemented by a design on a gold signet-ring of the religious class recently found at Thisbê and published here for the first time. On this we see the Holy Mother seated with the Babe on her knee and approached with gifts by adorant chieftains, remote predecessors of the Magi.

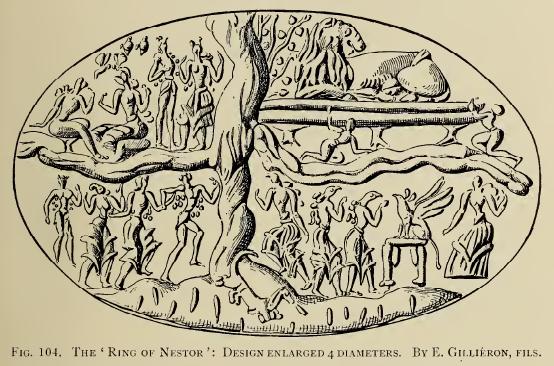

It will be seen that from the point of view of Comparative Religion this evidence — like that supplied by the subjects on the 'Ring of Nestor' — is of the highest interest.

3:

Page 145 in the

book,

page 195 in the PDF file.

In his description of that ring he says3 "The ring is so remarkable that it deserves a special consideration here." Well, his description of the ring is itself so remarkable that it deserves a special consideration. Omitting the footnotes in the original:

The ring itself is so remarkable that it deserves a special consideration here. It was found in a large beehive tomb at "Nestor's Pylos" by a peasant in quest of building material there, somewhat previous to the investigation of its remains by the German explorers in 1907. The discovery, however, was kept dark, and on the death of the original finder the ring passed into the possession of the owner of a neighboring vineyard. Thanks to the kindness of a friend, I saw an imperfect impression of the signet at Athens which gave me, however, sufficient idea of the importance that it might possess. I at once, therefore, undertook a journey to the West Coast of the Morea, resulting in the acquisition of this remarkable object, which, from the popular name given to the tholos since Dr. Doerpfeld's investigations, is conveniently described as the "Ring of Nestor".

And so there is no record of the object being found at the cited location. Supposedly a peasant looking for building material found it, and then passed it along to a local vineyard owner. Evans somehow sees "an imperfect impression" of it. If by "impression" he means the result of pressing the ring into clay or similar, there's no room for that in his story. And if he means a sketch providing some observer's impression of what it looked like, still, when was it observed by anyone other than the two farmers?

No matter — Evans will dash to the West Coast of the Morea, that being an antiquated name for the Peloponnese peninsula, a large and rugged region, and miraculously acquire it.

Here is this "Ring of Nestor":

The "Ring of Nestor" as depicted in Figure 104 from Volume III of The Palace of Minos at Knossos, Sir Arthur Evans, 1930.

He first discusses the tree that divides the design into four compartments, comparing it to Yggdrasil of Norse mythology, "early Oriental traditions of the 'Tree of Paradise'", and sacred trees from world religions in general.

Then he expounds on the "butterflies and chrysalises", the four small blobs in the upper left quadrant by the two pairs of standing and seated figures. He cites his tame entomologist whom he has trained in the nuances of finding exactly what Evans is looking for, and who has helpfully identified the precise species of butterfly that these must be. Then there's a lengthy footnote in which "Only unacquaintance with this generalized Minoan version could have led the Swedish entomologist Dr. S. Bengtsson" to fail to make this identification. We're told that this failure led to astonishment on the part of Evans's entomologist.

The presence of that specific species of butterfly leads to discussion of surviving Cretan folk traditions, paralleled by folk traditions around the world, all of which just happen to support the very story Evans wanted to tell.

The figure in Evans's book credits the drawing to the younger of the father-son Gilliéron artist team. But the original ring was most likely created in the very workshop in which the Gilliérons worked. So maybe Gilliéron fils was proud of how his gold work had been accepted. Or maybe it was an awkward situation, being tasked with making a drawing of the "discovery" of a piece that he may have been involved in creating.

By 1930 the staff in Evans's workshops had been drinking the art forgery Kool-Aid for three decades. Everyone had learned to deal with creating things to be "discovered" and then dealing with the ripple effects of what that could lead to.

The Boy-God

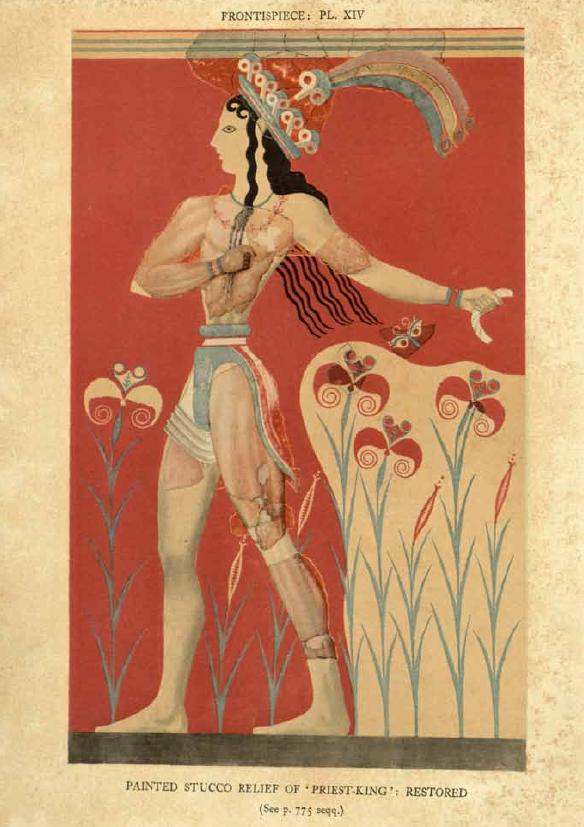

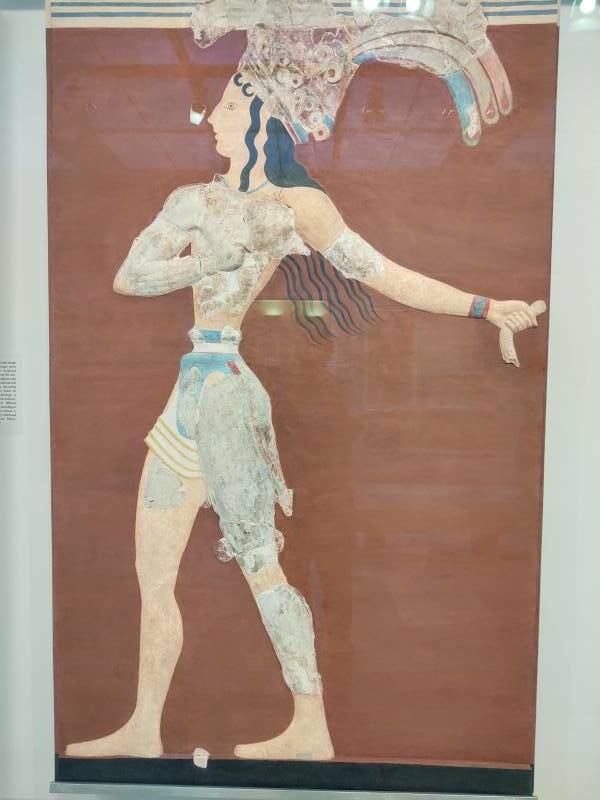

Evans opened his Volume II with a color frontispiece depicting a Priest-King or, as he described this figure in later volumes, a Boy-God.

Frontispiece, Plate 14 of Volume II of The Palace of Minos at Knossos, Vol II, Pt I, 1928

A replica representing "the location where it was discovered" is toward the south end of the complex today.

But it wasn't discovered, it was assembled. This was an especially bold forgery by Evans. Above is the original forgery in the Archaeology Museum in Heraklion, described there somewhat vaguely as formed from three fragments and "problematic". Is it ever.

The original material associated with the head is just the elaborate headdress and the top third of the left ear. That ear fragment is all that this component contributes to the body. It is facing to the viewer's left. The face and hair were painted at Evans's direction.

The legs are mostly represented with the left thigh, plus fragments of the left calf, a codpiece (of course), and a small fragment of the right thigh. These are also oriented from a figure facing to the viewer's left.

Then the torso is clearly from a different figure than that of either of the pieces so far, as it faces to the viewer's right, almost 180° away from the other parts.

This was another example where the original indicated genders of the components of the figure did not agree with Evans's story for several reasons. And so it required more tales of an androgynous tradition in Minoan society and art, plus "sexual transformation".

He had his artists working to support the story of the Boy-God who was the offspring and the consort of the Mother Goddess. Here is another example of how he had the Gilliérons creating "restored drawings" of figurines created in their workshops. These are the statuettes that the above cites Evans being amazed at how they "correspond within a millimetre or so in measurement". But they were both made in his workshop, so of course they fit together!

Figure 318 from page 526 of The Palace of Minos at Knossos, Vol III, 1930.

The End of the Minoans

In 1177 BCE, the eighth year of Pharaoh Ramses III's reign, Egyptian records describe an attack by a mysterious group that modern scholars call the "Sea Peoples". They had caused trouble thirty years before, in 1207 BCE. The Egyptians say that this time they set up camp on the coast of today's Syria and then moved south through Canaan and into the Nile delta.

All the other flourishing Late Bronze Age civilizations — the Minoans, Mycenaeans, Hittites, Assyrians, Kassites, Cypriots, Mitannians, and Canaanites — collapsed right around this time, rapidly fading away and disappearing within a century. Egypt continued, but in a much reduced state.

Some have blamed the "Sea Peoples" for the Late Bronze Age Collapse. But where did they come from, what were they like, and where did they disappear to?

More recent study has concluded that it's much more likely that the collapse was caused a combination of effects. The "Sea Peoples" were more likely a mix of opportunists and refugees, and not well-organized marauders.

The widespread collapse was partly due to the interconnected nature of those empires. The main technology for tools and weapons was bronze, but that requires tin and the only source at the time was mines in what today is Afghanistan. Tin was mined and refined there, then moved west through a complex trade network spanning several civilizations. Some scholars have compared tin in the Bronze Age to petroleum in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

There was a series of severe earthquakes in the Eastern Mediterranean from 1225 to 1175 BCE.

A climate change led to drought and famine during approximately 1200–850 BCE.

Power and control were concentrated in palace structures, so when the palace fell, that civilization would fold. Colin Renfrew of Cambridge University suggested back in 1979 that the Late Bronze Age Collapse could be explained as systems collapse. A huge and complexly interconnected system got increasingly out of control, and just fell apart when perturbed by a wide range of simultaneous problems.

Paper in Nature Overview in NatureThe paper "Severe multi-year drought consistent with Hittite collapse around 1198–1196 BC", published in Nature in February 2023, reported on a study of tree rings at Gordion in central Anatolia. There was a shift to drier, cooler climate conditions around 1200 BCE, but it was very gradual. The new study found "an unusually severe continuous dry period from around 1198 to 1196 (3±) BC". As they describe, argriculture and food storage in that region and era could withstand a year of drought. But two consecutive years would lead to a society's collapse.

Visiting HatuşaşTheir study was at Gordion and Hatuşaş, which had been the capital of the Hittite Empire for centuries. They speculate that this drought could have caused the collapse of the Hittite Empire, and possibly been at least part of the general societal collapse around the eastern Mediterranean.

1: Lincoln Logs were invented around 1916 by a son of Frank Lloyd Wright, an architect involved in the Modernist movement of which Evans's Knossos re-invention was a part.