Borganes and the Golden Circle

The Golden Circle

I had just spent three weeks driving all the way around

Iceland, following the Ring Road,

Iceland's Highway 1, for much of the way.

Now I would stay in Reykjavík for a few nights,

filling in some gaps.

I would return north to

Borganes to visit the

Settlement Center and see some sights

associated with the earliest Norse settlers,

especially Egill Skallagrímsson.

Then I would visit Þingvellir,

the home of the world's oldest democratic parliament.

Also shown and described here —

Geysir and Gullfoss,

the other two of the three classic sights of the

Golden Circle.

Borganes

Nes is Old Norse for "point". Many places in Orkney include "nes" or "ness" in their name. So, this is "Borga Point".

Skalla-Grímur Kveldúlfsson was involved in a bloody feud with King Haraldr Fairhair of Norway. The king had Skalla-Grír's brother Þorolfr killed, and then Skalla-Grímur and his father Kveldúlfr killed all but two people on a ship of the king's allies, including two of the king's cousins. Skalla-Grímur and his father fled Norway for Iceland.

Being a warrior–poet like so many early Icelanders, Skalla-Grímur composed a short poem about the episode.

gengr ulfr ok örn of ynglings börn.

Flugu höggvin hræ Hallvarðs á sæ.

Grár slítr undir ari Snarfara.

now wolf and eagle tread on the king's children.

The hewn corpses of Hallvarðr [Hallvarðr Harðfari and his people, Kveldúlfr's enemies) flew into the sea;

the grey eagle tears the wounds of Snarfari [Sigtryggr Snarfari, the brother of Hallvarðr Harðfari].

Kveldúlfr died on the sea voyage to Iceland. It is said to have been because he was weakened, having gone into a berserker rage at an advanced age while attacking King Haraldr Fairhair's allies. Following the Viking custom, Skalla-Grímur put the coffin in the sea and then built his settlement where it came ashore, near the below viewpoint in today's Borganes. He raised his boy Egill Skallagrímsson in this area.

Borganes has about 2,000 people, it's the hub of western Iceland.

The Landnámssetur or Settlement Center by the port of Borganes has two major exhibits. One explains the settlement of Iceland in general. The other is about Skalla-Grímur and Egill and the history described in Egil's Saga.

Egill Skallagrímsson composed his first skaldic poem at the age of 3.

When he was seven, he was playing a game with some local boys when one of them cheated Egill. Egill went home, got an axe, returned, and killed the boy who had cheated him. "Split his skull to the teeth" as the saga put it. It was an early start to his warrior–murderer–poet career.

The Settlement Center recommended using the Locatify SmartGuide, which was very nice for a tour of Borganes.

This mound represents Skalla-Grímur's burial mound. He had been buried here, or close to here, with his horse, weapons, and tools. Egill Skallagrímsson later had his father's burial mound opened so Böðvarr, Egill's son and Skalla-Grímur's grandson, could be buried here.

The burial mound was recently recreated here in Skallagrímsgarður, Skallagrím's garden or park.

Grani was a crew member on trip from Norway to Sweden. He settled here at Granastaðir, Grani's Farm. His son, Þórður Granason, was a childhood friend of Skalla-Grímur's son Egill Skallagrímsson, the subject of Egil's Saga. Skalla-Grímur's home at Borg á Mýrum was near the buildings visible in the distance at left.

One day in the winter when his son Egill was twelve years old, Skalla-Grímur was playing a ball-game, possibly somewhat similar to today's hockey, with Egill and Egill's friend Þórður.

The boys were winning. Skalla-Grímur lost his temper and threw Þórður down onto the ice hard enough that it killed him. Then he went after Egill.

Egill's nanny Þorgerður Brák intervened, keeping Skalla-Grímur from killing his son Egill. This redirected Skalla-Grímur's rage against her. He chased her all the way through the settlement to the port area, where she jumped into the sea and started swimming to an island out beyond the harbor. Skalla-Grímur threw a large rock at her, striking and killing her.

So, just a routine early Icelandic family hockey game.

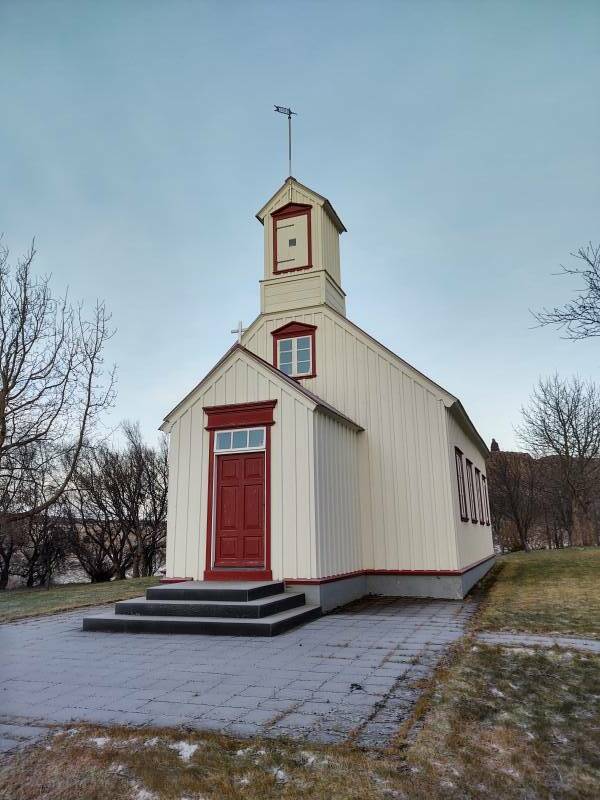

Below we're up on the volcanic plug or borg overlooking Borg á Mýrum, the site of the home that Skalla-Grímur built when they arrived in Iceland. Beyond the church is the frozen bay where Skalla-Grímur killed Þórður and was ready to kill Egill. Beyond the bay is the town of Borganes, and beyond that is the peninsula where Skalla-Grímur chased and killed Egill's nanny Þorgerður.

Egill lived to the old age of ninety or ninety-one. He killed many more people and composed many more poems. Along the way he continued his family's feud with the Norwegian royalty. Norway's King Eiríkr Bloodaxe and his queen Gunnhildr, said to have been a Finnish–Sami witch, spent the rest of their lives trying to has Egill killed.

After killing several of the King's men including his son Rögnvaldr and Queen Gunnhildr's brothers, Egill erected a níðstang or a nið pole, a traditional cursing device. It was a tall wooden pole with the head of a recently killed horse at the top. You turned the horse head to face the target of the curse, and often the curse would be carved in runes on the pole. Egill set up his níð on an island off the coast of Norway, facing the King and Queen. The saga says, in chapter 60 of an 1893 translation into English:

And when all was ready for sailing, Egil went up into the island. He took in his hand a hazel-pole, and went to a rocky eminence that looked inward to the mainland. Then he took a horse's head and fixed it on the pole. After that, in solemn form of curse, he thus spake: "Here set I up a curse-pole, and this curse I turn on king Eric and queen Gunnhilda. (Here he turned the horse's head landwards.) This curse I turn also on the guardian-spirits who dwell in this land, that they may all wander astray, nor reach or find their home till they have driven out of the land king Eric and Gunnhilda." This spoken, he planted the pole down in a rift of the rock, and let it stand there. The horse's head he turned inwards to the mainland; but on the pole he cut runes, expressing the whole form of curse.

There has been a church here at Borg á Mýrum since soon after Iceland adopted Christianity nation-wide in 1000 CE. This particular structure was built in 1880.

It's aligned north-south, which is unusual for a church in Iceland where most lie east-west.

Snorri Sturluson, the chieftain and writer, lived here at Borg in the 13th century. He is thought to be the author of Egill's Saga.

Kjartan Ólafsson is one of the main characters in the Laxdæla Saga.

Kjartan was Egill's grandson, the son of Egill's daughter Þorgerður Egilsdottir. The local people had found this hexagonal stone with an inscription in runes. They couldn't read the runes, but thought that it made a nice grave stone for Kjartan.

However, the actual rune-inscribed stone is now in a museum in Reykjavík. This is an accurate recreation of it.

Þingvellir

Within 50 to 60 years of the first settlement around 870 to 874 CE, Iceland's population had grown to about 15,000 people. Most of the people were involved in farming. They were scattered around the island in isolated settlements. Around 930 CE, the Icelandic chieftains began holding an annual meeting or Alþing in a location near Reykjavík that came to be known as Þingvellir. This annual meeting eventually evolved into today's Parliament of Iceland.

The allsherjargoði or grand chieftain, a high priest of the Norse pantheon, would call the meeting to order and would sanctify the meeting before the gods. He would be a direct descendant of Ingólfur Arnarson, the first Icelandic settler of Reykjavík according to the sagas.

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge separates the North American Plate from the Eurasian Plate. It's a spreading or divergent boundary between tectonic plates. In Iceland it's above sea level, where it's also called the Neovolcanic Zone.

The plates spread further apart by an average of 2.5 cm per year. This leads to many rifts along the boundary area. The one we're looking at here enlarges within a few hundred meters into the Þingvellir site.

Looking the opposite direction, here's a narrow rift just off the road near Þingvellir.

We're looking roughly to the north, so it's the North American Plate on the left and the Eurasian Plate on the right.

The Alþing meeting took place in Almannagjá or Everyman's Gorge.

The western or North American side of the gorge is the original layers of hardened lava. That's what we're looking at below. The eastern or Eurasian side in this area has fallen into the gap as it spread.

The Öxará river drops into the rift over the Öxarárfoss waterfall, which was mostly frozen when I visited.

The broad open area along the lower stretch of river would have been filled with camps during an Alþing meeting.

The Lögsögumaður or Law Speaker would stand at or on Lögberg or the Law Rock and recite the guidelines for the meeting, the outlines of Icelandic law, and the highlight's of the last year's meeting.

The Law Rock is now marked with a flagpole.

The Lögrétta or Law Council would meet on the other side of the river, reviewing and debating existing and proposed laws. The Law Speaker was responsible for memorizing all that they decided.

Around 999 Iceland was headed for civil war as King Olaf I of Norway was pressuring Iceland to convert to Christianity. The King had taken several hostages, relatives of high-ranking Icelander who had been in Norway. The King threatened to kill all of them if Iceland did not convert to Christianity. So, there was a pro-conversion faction in Iceland, but many of those without relatives held hostage were against it.

Þorgeir Þorkelsson was the Law Speaker. He was a moderate, trusted by those on both sides of the argument. The Alþing asked him to make the decision.

Þorgeir rested under a fur blanket for a day and a night, thinking it over. Then he announced that Iceland should adopt Christianity. But with the conditions that eating horse meat, killing unwanted infants, and private worship of the Norse deities would remain legal.

In 1262 the chieftains entered into union with Norway in what was called the Old Covenant. They pledged fealty to the King of Norway, and the Alþing remained an annual meeting but now it was an appeals court. That continued through 1798. The Alþing was suspended from 1799 until 1844.

Iceland gained sovereignty after World War I. On 1 December 1918 it became the Kingdom of Iceland, sharing the monarchy with Denmark.

Nazi Germany occupied Denmark on 9 April 1940. The Parliament of Iceland took temporary control of foreign affairs and the Coast Guard, and elected a provisional governor who went on to become the country's first president. British military forces began a peaceful invasion of Iceland on 10 May 1940, and first British and later American forces operated from the country.

The 1918 Act of Union with Denmark expired at the end of 1943. The following May, Icelanders voted on whether to terminate the personal union with the King of Denmark and establish their own republic. The vote was 97% in favor of ending the union, and 95% in support of the new constitution. The Danish King Christian X sent a message of congratulations from Nazi-occupied Denmark when Iceland declared itself an independent republic on 17 June 1944.

Preparing for Ice

I had visited Geysir and Gullfoss, the other two points of the Golden Circle, back at the start of my trip. They were a fairly short day trip north from Eyrarbakki.

The weather then had been less cold, leading to a lot of wet ice. My car had studded tires. I needed something for my feet. These bright orange strap-on crampons did the trick at Geysir, Gullfoss, and several other slick areas during my trip.

They're tough stretchy rubber with a velcro band that fastens over the top.

Geysir

Geysir literally means "The Gusher" in Icelandic and Old Norse. Its name was adopted as geyser in English to refer to all occasionally spouting water features.

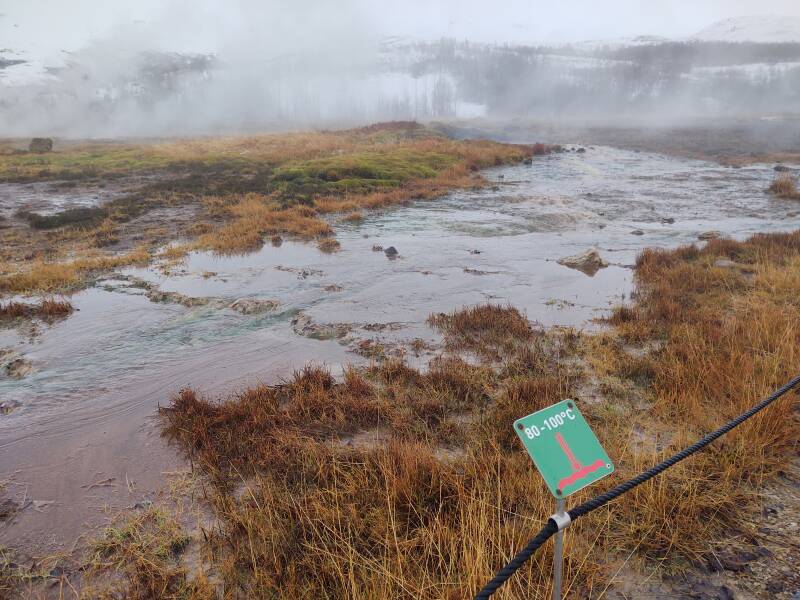

There are several spouting geysers and boiling springs here at the Haukadalur geothermal area along the Hvitá river.

These geothermal features change over time. Earthquakes can create, stop, and restart a geyser. The classic Great Geysir sprayed water to a height of 50 to 170 meters during the mid 1800s, but became mostly dormant until an earthquake in 1896 restarted it.

Now the Great Geysir is largely quiet, with activity about three times per day.

The water is boiling hot. This blunt warning sign tries to warn the unwary tourists.

You need to stay on the marked path, as the stream is barely below the boiling point.

Litli Geysir or Little Geysir is along the path.

Strokkur or "Churn" is the new star here.

It usually erupts every six to ten minutes, spraying boiling hot water 15 to 20 meters high, although sometimes as high as 40 meters.

Everyone gathers and waits.

After a few eruptions, you spot the pattern. The wide pool begins to churn as its name says. A large blob of steam is about to appear, throwing hot water high into the air.

Let's see it in motion. The excitement happens around 45 seconds into this video.

Gullfoss

I continued on to Gullfoss, and put my crampons back on. No, you don't try to drive a car with a 5-speed manual transmission while wearing crampons. Nor do you go indoors wearing them.

But you need to wear them outdoors at many interesting places in Iceland.

Gullfoss or Golden Falls is where the Hvitá river turns sharply to its right about a kilometer above the falls, flows down a wide curved "staircase", and then drops in two stages of 11 meters and 21 meters into a crevice about 20 meters wide.

The SleipnirTours.is company runs tours with a large 8-wheeled off-road bus named for Oðinn's 8-legged horse.

Finally, to Keflavík

It was about a 40 minute drive from downtown Reykjavik out to the Keflavík airport. I had to get a COVID-19 test within 24 hours of boarding the plane to the U.S. I did that right before fueling up my car, turning it in, and taking the shuttle van to the airport.

The Ring Road is 1,322 kilometers long. I had driven a total of 2,783 kilometers, a little more than twice the distance of a simple circuit of Highway 1 because of all the side trips. Extra fjords, east to Seyðisfjörður, around the Tröllaskagi peninsula, and many short diversions. It was a great trip!

as in this;

Þ/þ is unvoiced,

as in thick.