Edinburgh and Arthur's Seat

Edinburgh

Edinburgh, Scotland's capital, is built on

cores of ancient volcanos.

The rugged terrain made for more easily defended hill forts

in prehistoric times, leading to fortifications in the

Middle Ages, and on to today's city.

The tallest of these volcanic plugs,

Arthur's Seat,

is in a city park that includes several other examples

of Highland terrain.

It's a pleasant walk to the summit of Arthur's Seat,

with great views over the city and its surroundings.

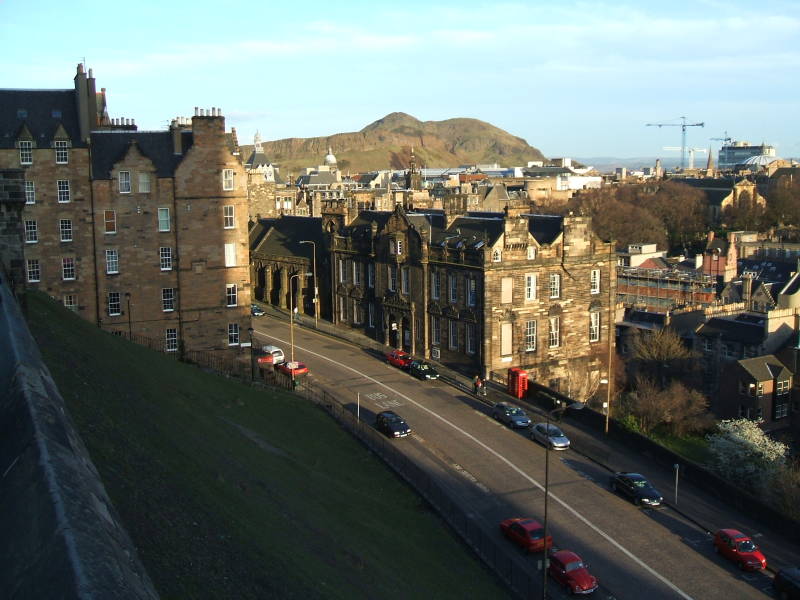

Below is the view from Castle Rock,

the second-tallest volcanic plug in Edinburgh.

We're looking south-east over part of the Old Town

toward Arthur's Seat.

The nearest building directly below the peak of Arthur's Seat

is home to the

Castle Rock Hostel,

a nice place to stay in Edinburgh.

They also operate hostels further north in Scotland,

in Pitlochry, Oban, Fort William, Skye, Inverness,

and Loch Ness.

Edinburgh Castle is built on the top of a volcanic plug created around 350 to 400 million years ago. It's the remains of a volcanic pipe which cut up through the surrounding sedimentary rock and cooled to form very hard dolerite, a type of basalt.

Glaciers came along much later, moving east-northeast. The hard dolerite plug was eroded, but not nearly as much as the surrounding sedimentary rock. Geologists call the result "crag and tail", where the hard plug protects the softer rock downstream.

The peak of Castle Rock is 130 meters above sea level. The cliffs on its north, west, and east sides drop 80 meters. The Royal Mile is the main street leading down the ridge, the narrow glacial tail, to the east-northeast.

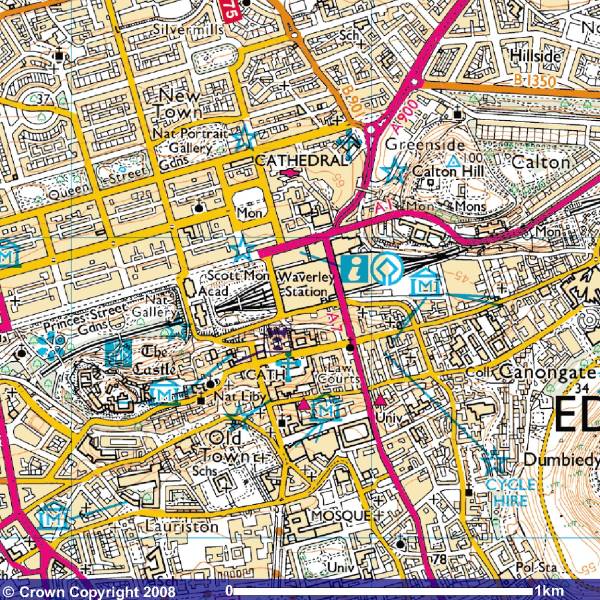

A low-lying area along the north side of the Royal Mile was the Nor Loch. City engineers drained it in the 1820s. The rail lines and Waverly Station are now there, along with the National Gallery and other cultural sites. Waveryly Station is the second busiest in Scotland, behind Glasgow Central. It's the fifth-busiest in all of Britain outside London, and the second largest in area and number of platforms in all of Britain.

The New Town area was already being built up when Nor Loch was drained. It was designed in the 1760s with an orderly rectangular grid. That was just the thing for the Scottish Enlightenment underway at the time. The Old Town area to the south kept its old curving streets.

Down The Royal Mile

We're looking up at Edinburgh Castle from just part of the way down the steep slope to its south. We're just across the street from the Castle Rock Hostel, which is on the next street down the slope. There's a lot of up and down when you move around Old Town.

People have lived in the area since the Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age. A nearby camp dates to around 8500 BCE. Settlements of the later Bronze Age and Iron Age, corresponding in Britain to about 2100–750 BCE and 800 BCE to 100 CE, respectively, have been found on Castle Rock and Arthur's Seat.

The Romans arrived at the end of the first century CE, finding a Brittonic Celtic tribe they described as the Votadini. Ptolomy's map of the second century showed a Votadini settlement named Alauna, meaning "rock place", possibly a reference to Castle Rock. The Votadini people merged into a regional kingdom in the early Middle Ages, starting around the 400s. In their language, Cumbric, they called the settlement Eidyn, and Din Eidyn was their din or hillfort.

The epic Welsh poem Y Gododdin referred to Din Eidyn, telling of the Gododdin people, descendants of the Votadini. It describes how the Gododdin King Mynyddog Mwynfawr and his warriors feasted in their fortress for a year, then set out to battle the Angles in Yorkshire. Where, unsurprisingly how they had prepared, they were massacred.

Forces of King Oswald of Northumbria besieged Din Eidyn in 638, and the control of the area passed to the Angles. The Scots took it in the 900s. As the local language became Old English, then Middle English and then Scots, the Brittonic Din Eidyn and Scottish Gaelic Dùn Èideann became Eidyn burh.

Macbeth's grave onthe Isle of Iona

The first historic record of a castle here is in John of Fordun's account of the death of King Malcolm in 1093. This is soon after the reign of Macbeth, who was King of the Scots 1040–1057. Mind you, Macbeth's title was King of Alba, he ruled just part of today's Scotland, and probably not exactly as described in Shakespeare's play.

Amazon

ASIN: 0743477103

Amazon

ASIN: B01BD6AD10

Excavations in 2014 identified 26 sieges in the 11-century history of the castle. The location has obvious defensive advantages. However, the basalt plug formed as a cooling vertical pipe of magma. It's extremely hard and non-porous. It's hard to drill a well into it, and even if you manage to, you won't get much water. Water supply was often the limiting factor on sieges.

By the 1300s, foreign chroniclers such as Jean Froissart were describing Edinburgh as the capital of Scotland.

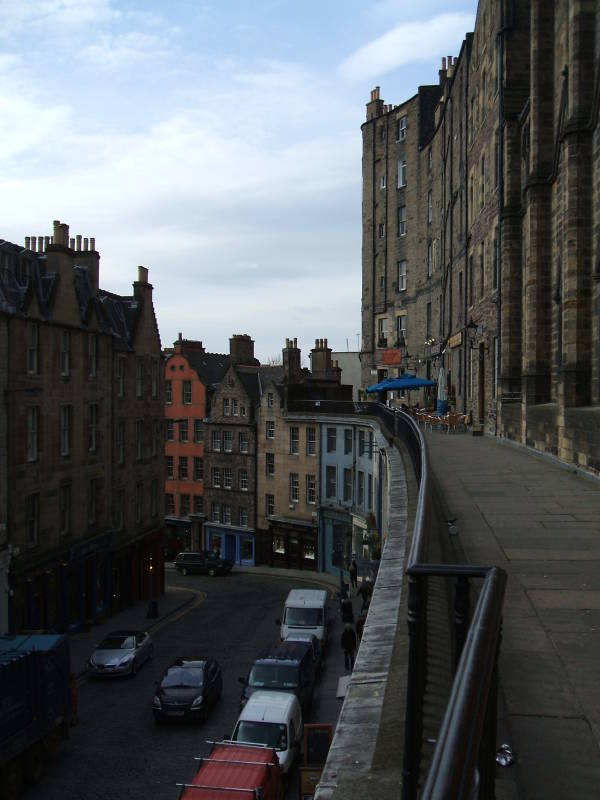

Old Town buildings are tall and narrow, with tight passageways between them.

The ridge of the Royal Mile was narrow, so it filled quickly and people built taller and taller structures. By the 1500s, multi-story residential buildings called lands became the norm. The city's defensive walls still contained the city in the 1600s, as the population increased and buildings grew even taller. They were typically ten or eleven stories tall. Robert Chambers' book Notices of the Most Remarkable Fires in Edinburgh: From 1385 to 1824 reported that at least one reached fifteen stories by 1700, at which point it burned.

In the late 1800s in the U.S., the term "skyscraper" began to be applied to buildings of steel frames and at least 10 stories. So, maybe taller but fewer stories than the buildings in Edinburgh up to two centuries before.

These buildings along the top half of the Royal Mile only show 5 or 6 stories on the street side. But the ground falls away, and their back sides are several stories taller. Also, as people continued to move into the city during the Industrial Revolution, vaults were excavated below street level on the downhill sides. The new immigrants lived in these basement tenements.

The sequence of streets running down the Royal Mile are actually Castlehill from the castle down to a roundabout, then Lawnmarket, High Street (which is British English for what North Americans call "Main Street"), and then Canongate down to the bottom end.

The major north-south street South Bridge roughly marks the middle of the Royal Mile. It crosses about half way from the Castle to the bottom end, the Scottish Parliament, and Holyrood Palace. South Bridge becomes a literal bridge over the former Nor Loch area, crossing above part of Waverly Station.

About half-way down from the castle to South Bridge we come to St Giles' Cathedral or the High Kirk of Edinburgh, known as the "Mother Church of Presbyterianism". There was a church here in 854. King Alexander I rebuilt it in the Norman style in 1120. The current structure dates from the late 14th century, although with extensive restorations in the 19th century.

Walking down from the castle, we have come to the statue of the philosopher David Hume, who graduated from the University of Edinburgh. Closer to the Kirk is a statue of Walter Francis Montagu Douglas Scott.

Hume, who lived from 1711 to 1776, is a leading figure of the Scottish Enlightenment. He's probably best known for what's called "Hume's problem of induction", in which he argued that inductive reasoning and belief in causality cannot be rationally justified.

On ethics, he argued that morality cannot be based on reason. "Hume's Law" denies the possibility of logically deriving what ought to be from what is, or deriving morality from reason.

He was accused of atheism, or at least heresy, and couldn't get a position as a university professor. But he had a successful career as an essayist and a librarian at the University of Edinburgh.

Several narrow closes or alleyways lead off between buildings to the north and south of the main street.

Yes, there are plenty of places selling kilts and other stereotypical Highland garb to the tourist trade.

Plaid isn't the pattern, a "plaid" refers to either a tartan pattern blanket or a tartan pattern cloth worn over the shoulder as an accessory to a kilt.

Tartan refers to a sett, a pattern of crossed horizontal and vertical bands in multiple colors. The Dress Act of 1746 made it illegal to wear tartan. This was part of England's attempt to pacify the Highlands. It was repealed in 1782 through the efforts of the Highland Society of London.

And now, to debunk some tartan legends:

Cloth in tartan pattern wasn't invented in Scotland. The Halstatt culture of central Europe produced tartan-like textiles in the 8th to 6th centuries BCE. Similar textiles were found with mummies from the Tarim Basin and Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang. In Scotland, a simple tartan pattern was found at Falkirk, dating from the 3rd century CE.

Tartan patterns weren't associated with specific clans. Not originally, anyway. The patterns were associated with the weavers, and the availability of dye or dyed thread. Everyone from a given isle or region wore similar patterns. Sir Walter Scott's writings popularized the idea of Scottish identity and wearing tartan. "Clan tartans" are a recent tradition invented in the early 1800s.

Meanwhile, the Highland Clearances were evicting the largely Gaelic-speaking inhabitants from the Highlands. The landlords, who would have been clan chiefs under the earlier system, replaced small farms with large-scale sheep grazing. Farming tenants were forced into crofting communities to work in fishing, quarrying, or kelp collection. Many ended up emigrating to North America.

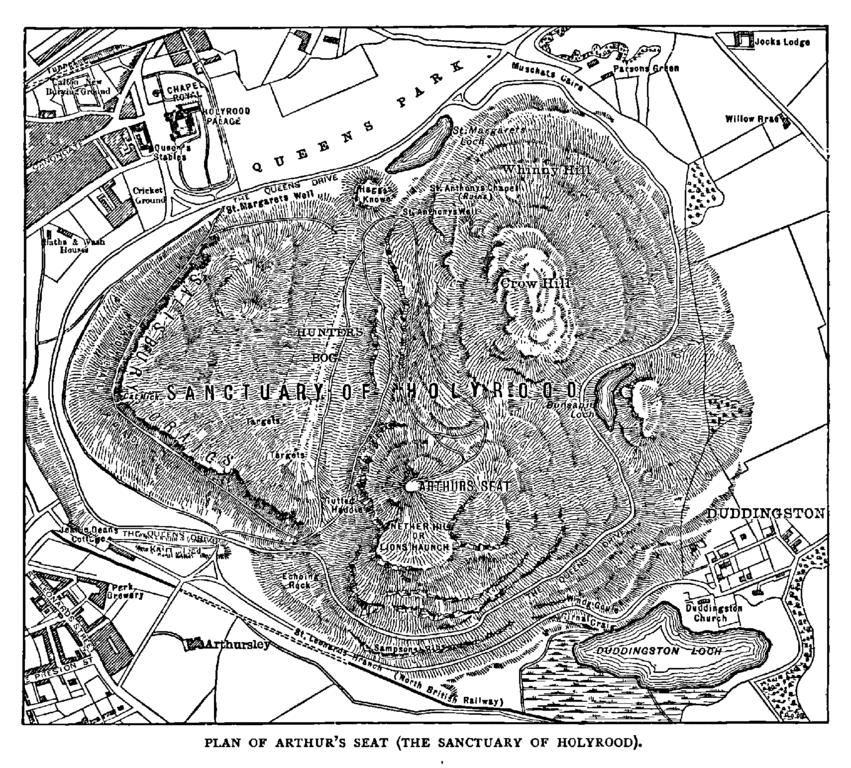

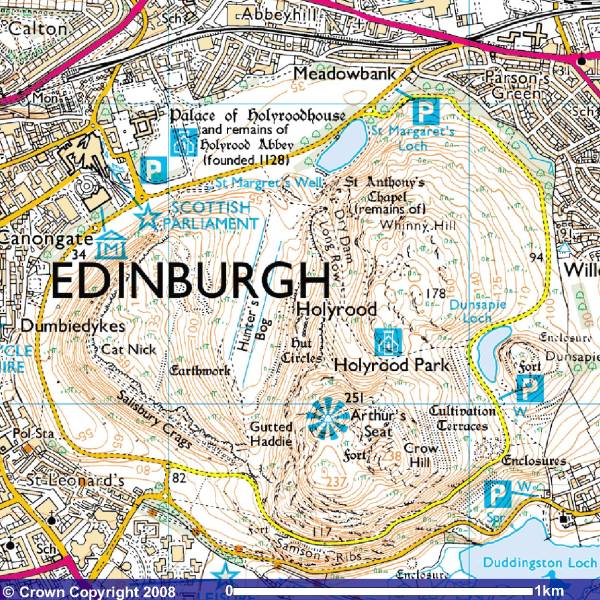

We're almost at the bottom of the Royal Mile. Here's a map from the 1880s showing Holyrood Park and Arthur's Seat:

Arthur's Seat

Arthur's Seat is the largest of the three volcanic plugs forming the landscape of Edinburgh. Below we're looking at it from Calton Hill, the smallest of the three.

King David I was hunting in the forests on the east side of Edinburgh one day in 1127. A stag or male deer, a hart as they said back then, startled his horse, who threw off the king. He thought the stag was about to trample him, or gore him, or micturate all over him, or whatever ill-tempered stags do. Then the king saw a cross between the stag's antlers.

Origins of Jägërmëïstër in BelgiumYes, it was yet another large stag with a miraculous shining cross between its antlers, which seem to have appeared so often during the Middle Ages in Europe. A variant of this happened in southern Belgium in the 15 century, leading to the development of Jägërmëïstër.

The king founded Holyrood Abbey on the site in 1128, "Holy Rood" being the medieval term for a piece of the True Cross. David's mother had what was purported to be a fragment of the True Cross, and David put it in a golden reliquary in the main church of the abbey. The English captured it at a battle in 1346. Well, David's mother had obtained it somehow from Waltham Abbey, near London. The English took the relic to Durham Cathedral, just south of Northumberland, the northernmost English county. They lost track of it at the Reformation.

The first stage of Holyrood Palace was built next to the abbey. It may have been a royal residence by the time Robert the Bruce died in 1329. David II died in 1370, and he was the first of several Kings of Scots to be buried there. James IV build a new palace next to the abbey in 1501–1505. It became the main residence of the Kings and Queens of Scotland.

Now the palace is the official residence in Scotland for the British monarch. What's here now was built in the 1670s.

The ruins of the abbey are next to the palace. An invading English army damaged the abbey in 1544 and 1547, stripping lead off the roof and taking the bells and many of the abbey's contents. Then Scotland developed a national Kirk during the Scottish Reformation. The Roman Catholic abbey was thoroughly plundered in 1559. Its church was used until the 17th century, but the roof collapsed in 1768. It's been a ruin ever since.

The bottom end of the Royal Mile takes you to Holyrood Palace and the Scottish Parliament. Holyrood Park, formerly a royal preserve and now an Edinburgh city park, is just to the south. This map shows some remains of Iron Age hill forts.

The Scottish Parliament Building opened in 2004. The Scottish Parliament itself was established in 1997.

Let's cross the street and start our walk up Arthur's Seat.

Saint Margaret's Loch was a boggy marsh. Prince Albert, Queen Victoria's husband, organized improvements in the area around the palace. He called for the bog to be excavated and turned into a small loch. The other two small lochs, Duddingston Loch and Dunsapie Loch, seem to be natural.

We can start to see the Firth of Forth. It's about four kilometers from the city center to the shoreline. Several rivers including the Forth drain through the Firth of Forth into the North Sea. Geologically, the firth is a fjord, scraped out during the last glacial period. The Norse sagas called it the Myrkvifiörd.

Its less than 50 kilometers from the Firth of Forth on the east coast to the Firth of Clyde on the west coast near Glasgow.

We soon reach the ruins of Saint Anthony's Chapel. There doesn't seem to be much history on this, beyond a record that the Pope gave money for it to be repaired in 1426. It may have been connected to the Preceptory of Saint Anthony. A preceptory would be the headquarters of an order of monastic knights. That one operated what is described as a skin hospice. Mottled skin can be a sign of approaching death. Or maybe it was for some class of dermatological problems. Anyway, as a Roman Catholic facility this chapel was probably abandoned in the late 1550s after the Scottish Reformation.

The spire of the High Kirk appears in the distance, in front of the castle.

On we go, up through a small glen or valley.

We can look back and see more of the Firth of Forth as we ascend. We're looking north over the port of Leith. The island in the firth is Inchkeith.

King James IV is said to have transported a mute woman and two infants to the isle of Inchkeith in 1493. It was an experiment, to see what language the children spontaneously began to speak when they grew up. That, you see, would be God's Language. It was all scientific, by standards of the day, when the king was considered to be a medical expert. As reported in Scots English in Robert Lindsay's The Cronicles of Scotland:

This king James the Feird was weill learned in the

airt of medicine, and was ane singular guid chirurgiane;

and thair was none of that professioun if they had

any dangerous cure in hand, bot would have craved his adwyse.

[...]

The king also caused tak ane dumb voman,

and pat her in Inchkeith, and gave hir tuo bairnes with hir,

and gart furnisch hir in all necessares thingis

perteaning to thair nourischment,

desiring heirby to knaw quhat languages they had

when they cam to the aige of perfyte speach.

Some sayes they spak guid Hebrew, but I knaw not

by authoris rehearse, etc.

Some of today's Evangelicals claim that people "speaking in tongues" are speaking fluent Biblical Hebrew, the language of ancient Israel. The two children banished to Inchkeith, however, never learned to speak at all.

This wasn't the first language deprivation experiment in history. Herodotus said that the Egyptian pharaoh Psamtik I did something like this, concluding that the children's babbling was Phrygian. The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II had some infants raised without human interaction, to test his theory that they would spontaneously begin to speak Hebrew. Because, well, Adam and Eve. Hopefully these three have been the only such experiments creating intentionally feral children.

Near the top end of the small glen we can see to the east, along the south shore of the Firth of Forth toward the North Sea, about 40 kilometers away.

Let's look around once we reach the top of the glen, turning from north to east.

Arthur's Seat produced the same "crag and tail" effect when the glacier moved across this area toward the east. We're looking northeast in the below picture, where we can see that there's a gentle slope down to the east.

That's Donsapie Loch to the east of the peak, seen above and below. There are rough remains of a fort on the small hill beside it.

Ben Nevis

We're nearing the peak. Arthur's Seat is a volcanic plug, so it's made of basalt. That's a fine-grained hard stone, about half silica or SiO2. The basalt of Arthur's Seat, like what makes up Ben Nevis, has a reddish color because of its oxidized iron content. There isn't grain or small-scale layering as there is with sedimentary rock, so the surface tends to be jagged and irregular. Walking on this can be hard on your knees and ankles.

We've reached the summit! Its peak is at 251 meters, so we've gained about 230 meters of elevation.

The large nearby buildings in the picture below are part of the University of Edinburgh.

It's the sixth oldest university in the English-speaking world, and recently ranked 18th best university in the world. It was established as a law school by King James VI of Scotland in 1582. Through the 1700s into the 1800s it was considered the top medical school in the world, and is still very highly ranked. Its science and engineering programs have been highly respected since they were known as programs of Natural Philosophy. It continues to be a leader in computer science. Its School of Informatics was recently ranked 12th in the world.

We're looking to the west in the pictures above and below. This is the direction the glacier came from. This upstream side of the hard basalt plug eroded much less than the surrounding sedimentary rock, leaving a steep western slope that the glacier divided to flow around.

Below, we're looking toward Castle Rock, about two-thirds of the way to the right of the picture. We're looking out over the edge of the Salisbury Crags, a series of basalt cliffs.

You can see Holyrood Palace, with the ruin of Holyrood Abbey.

Salisbury Crags

We've come down from the peak, and we're looking off the edge of the Salisbury Crags, a series of cliffs along the west side of Arthur's Seat.

Paths run along the top and bottom of the crags.

The glacier flowed against the volcanic plug from this side. It exposed the upstream face of the plug, breaking off some of the hard basalt.

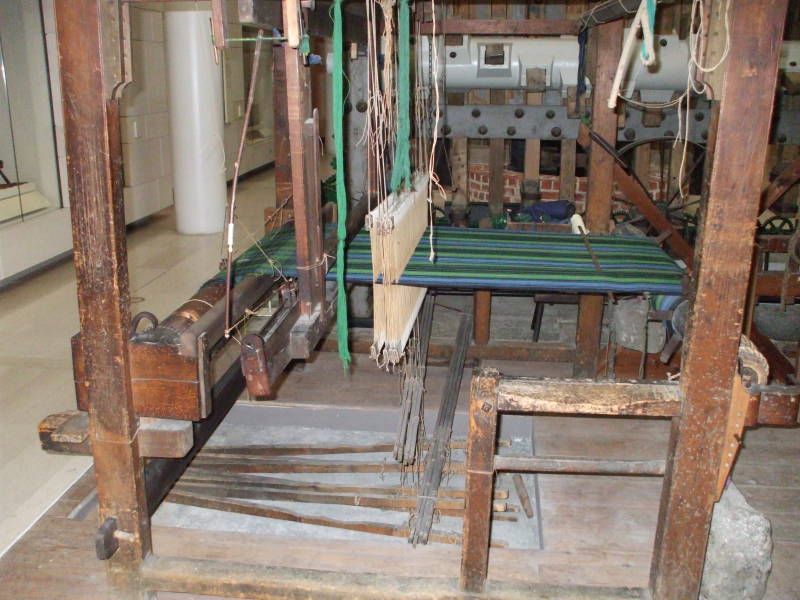

The path along the base of the Salisbury Crags is the Radical Road. The Radical War or Scottish Insurrection was a week of strikes and unrest in 1820. Workers, especially weavers, wanted government reform. The upper classes feared a Scottish version of the French Revolution, and the government deployed spies and informants.

The government crushed the movement, charging 88 men with treason. Some were executed, and 19 were transported to the penal colonies in Australia.

The government took up Walter Scott's suggestion, and paid some unemployed weavers to pave this track. It's still called the Radical Road.

A section of the Salisbury Crags is famous for being where the geologist James Hutton realized in the 1760s that the igneous and sedimentary rock deposits must have formed at different times and in different ways. A area within the Salisbury Crags is called Hutton's Section. It's where he observed that magma had forced its way through sedimentary layers to form the basalt sill.

The white building that looks sort of like a circus tent is Dynamic Earth, a nature museum.

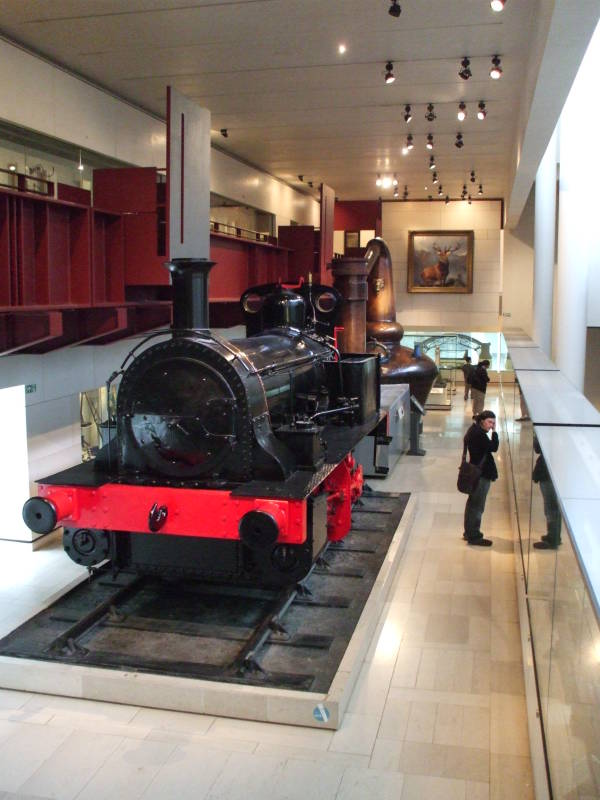

At the National Museum

The National Museum shows Scotland's strong tradition of science and engineering.

James Watt, who made the steam engine practical, was a Scot.

So was James Clerk Maxwell, whose equations did for electromagnetism what Isaac Newton's writings did for optics and mechanics.

The large object above is a still for making whisky, called uisge beatha in Scots Gaelic.

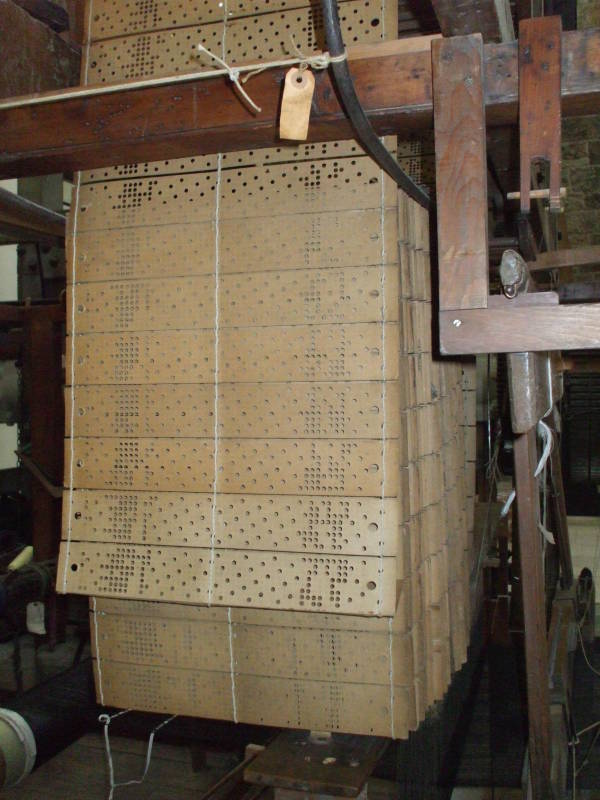

The museum also has some Jaquard looms, programmable machines invented in 1804.

A series of "cards", thin wooden sheets with patterns of punched holes, make up the program.

Each card allows a particular set of rods to move, raising certain threads. The resulting cloth has a pattern that was programmed by the series of card hole patterns.