Napoli (or Naples)

Napoli

Napoli, or Naples

as English speakers spell it,

is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities

in the world.

A Greek colony was founded here in the eighth century BCE.

It was re-founded in the sixth century BCE as

Νεάπολις

or Neápolis,

"New City",

the origin of today's name of Napoli.

Now it's Italy's third-largest city jammed into

the original Greek street plan.

It's loud, crowded, and chaotic.

It's easy to reach.

On my 2009 visit I flew Chicago—Rome—Naples

and then a bus into the city.

In 2025 I flew into Rome,

took the train that runs every 15–30 minutes

to Roma Termini, the city's main train station,

and from there it was just an hour and fifteen minutes

to the Napoli Centrale station

on a Frecciarossa high-speed train.

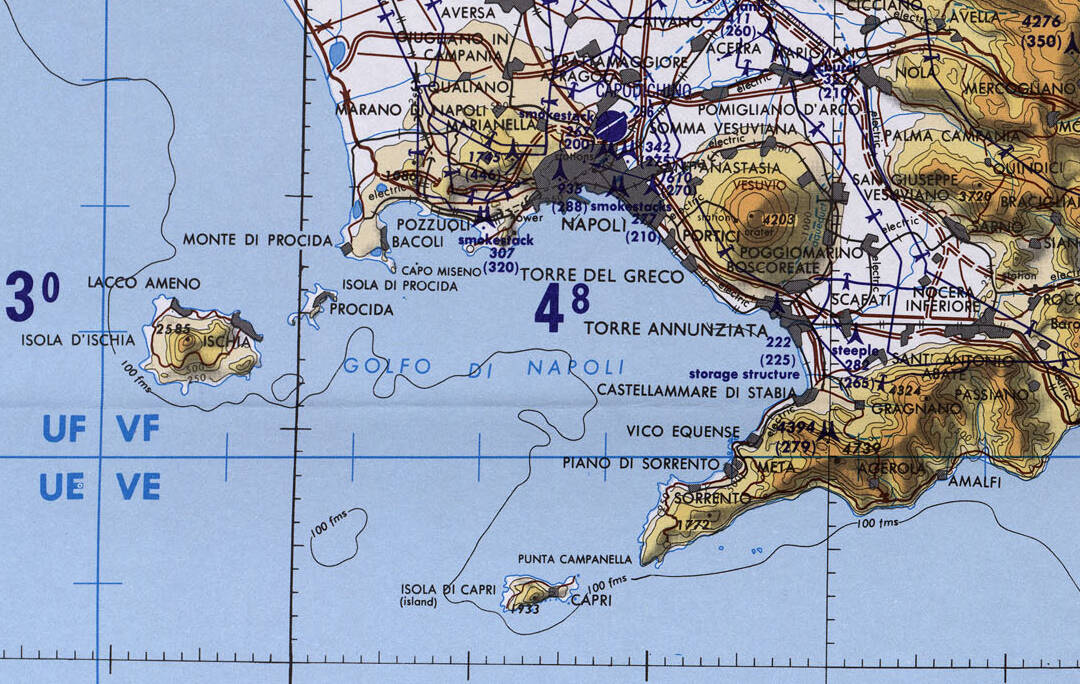

Portion of aeronautical chart TPC F-2D from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

Ancient Napoli

The Phlegraean Fields, a large volcanic caldera west of the city, have been inhabited since the Neolithic period.

Mycenaean sailors established a settlement in the area of today's Napoli during the second millennium BCE, during the Bronze Age. In the early first millennium BCE, Phoenician settlements colonized much of coastal Sicily.

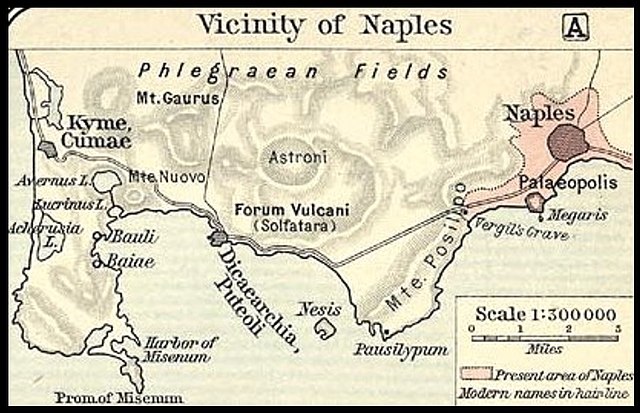

Map of the vicinity of Naples from the 1911 Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

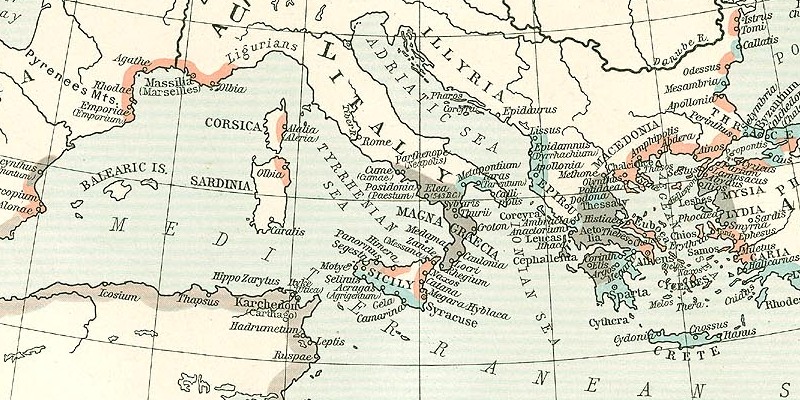

Later, the population of Greece was growing beyond what the arid country's agricultural system could support, and so Greek city-states established many colonies around the Mediterranean and Black Seas during the sixth through eighth centuries BCE. In some areas the arriving Greeks displaced Phoenician settlers.

Much of the peninsula of Italy south of Neápolis became part of Μεγάλη Ελλάδα or Megáli Elláda, Greater Greece, what the Romans later called Magna Graecia.

Portion of a map of Greek and Phoenician settlements from the 1911 Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. Pink is Ionian Greeks, blue is Dorian Greeks, grey is other Greeks, light purple faded to a lighter grey (e.g., African coast) is Phoenician.

A Greek colony called Παρθενόπε or Parthenópe was founded here in the eighth century BCE, on the Pizzofalcone hill overlooking the harbor. It was described as an island at the time.

Around 507 BCE a group of the aristocracy was expelled from the nearby city of Cumae. They arrived in Parthenópe and re-founded it inland from the harbor. The old settlement became Palaeopolis or "the old city", and they established their New City, Neápolis or Νεάπολις, with a grid of streets. It became a prominent city of Greater Greece.

Rome's army seized Neápolis in 325 BCE after a year-long siege. However, Neápolis remained largely autonomous and kept its Greek language and customs. Three hundred years later the people of Rome saw it as a center of Hellenistic culture, a place to perfect one's knowledge of Greek culture.

Neápolis was in the central province of the Roman Empire for as long as that Empire lasted. The Roman Empire fell apart and the Italian peninsula became a complicated quilt of independent kingdoms, duchies, independent city-states, Papal States, and possessions of overseas powers.

The Kingdom of Sicily eventually controlled most of the southern part of Italy, including Naples. It broke up in 1282, splitting into the continuing kingdom, based on the island of Sicily, and the peninsular land. Napoli became the capital city of the Kingdom of Naples, an independent kingdom covering the southern half of the Italian peninsula.

The Kingdom of Naples lasted from 1282 until 1816, which it again merged with the Kingdom of Sicily and the combination was called the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. It was by far the largest, and also the richest and most powerful of the many Italian states in the century before il Risorgimento or Italian unification in 1870.

A small population in the "heel" of Italy in the 21st century still spoke Griko, a language combining ancient Doric, Byzantine Greek, and Italian. As of 2007, an estimated 20,000 people, mostly elderly, still spoke Griko. The Ndrangheta is much like the Mafia, but in Calabria, the "toe" of Italy's boot, rather than Sicily. The word "Ndrangheta" is itself of Griko origin.

To My Lodging

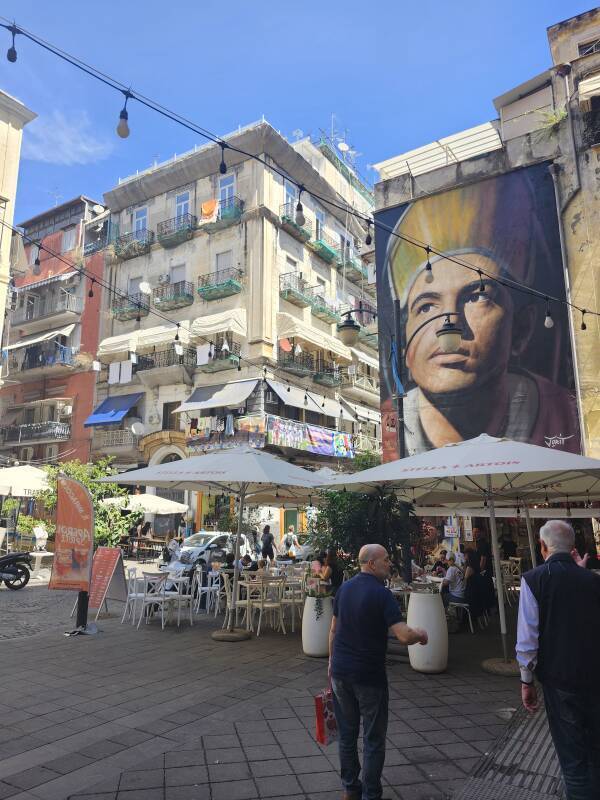

Napoli's Centro Storico or historic center was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995. Via dei Tribunali runs roughly east-west as the main axis of Centro Storico.

Guesthouses at Booking.comMy visit was in early May, I set up my lodging about a month before, in early April. I look for a place somewhere along Via dei Tribunali within luggage-transporting distance of the train station and the port. Places were already filling up. The 1.8-kilometer trek between the station and the Miraglia guesthouse dragging a roller bag emphasized how rough the streets and sidewalks of Napoli are. It's mostly irregular cobblestones.

Piazza Luigi Miraglia is one of many piazzas or squares that Via dei Tribunali runs through or adjacent to. I was looking for #386. When I first arrived, I used the appropriate buzzer to the right of the door, and my innkeeper remotely unlocked the door. Once I was checked in and had my ring of three keys, I would use the first one at the street. The door for people is entirely below the sprayed white "ORBS", and spanned by the sprayed blue "ORBS". You duck your head and step through the hatchway.

Once through the door and inside the arched passage toward the central court, you could unlock and unlatch the two large door halves to drive a car into or out of the building.

My innkeeper waved to me from the second floor up, the lowest one with glassed-in balconies, and told me which of four stairwells to enter.

Two floors up and then use the second key in the heavy wooden door.

Then, use the third key on my bedroom door.

No balcony or "City View" was promised in the online description, none was needed. It's not really a window, but it was a nice source of ventilation. My room was cool, quiet, and dark, great for its main purpose of sleeping.

A bathroom was right across the hall. Another shared bathroom also had a shower.

Japanese High-Tech ToiletsJapan is well-known for its sophisticated toilets, with heated seats that include adjustable bidet and air-drying functionality.

What is a Bidet?Italy should be just as well-known for the prevalence of traditional standalone ceramic bidets. During this trip I was in Italy for 38 days, and stayed overnight in twelve guesthouses. Ten of them had an arrangement like this. The two that lacked an independent bidet unit were very small apartments with bathrooms that were barely large enough for toilet, sink, and stand-up shower. Both of them had a flexible hose with spray nozzle, a taharet musluğu in Turkish or shattaf in Arabic. No, I have no idea what the terminology is in English, let alone Italian.

Centro Storico

Flânerie, the art of being a flâneurTo be a flâneur is to wander aimlessly while observing your surroundings and society. The Centro Storico is an excellent place for flânerie.

Many buildings are like the place I was staying, with large and heavy doors opening into open courtyards. Sometimes those doors are left open.

Buildings become joined by arches above the streets.

Chiesa dei Girolamini is a church built in 1592–1619 and its ecclesiastical complex, which includes an art collection and a large library.

This kilometer-long stretch of Via dei Tribunali is a "must see" area for visitors to Napoli, so it gets pretty crowded during part of the day.

Large tour groups started arriving mid-morning, when buses transport them from their cruise ship or hotel to an entry point. In late afternoon they clear out, but from about 10:00 to 16:00 Via dei Tribunali becomes crowded.

A guide wearing a headset and carrying a telescoping stick with a brightly colored banner marches along, gesturing broadly and narrating the sights. A group of thirty to fifty people follow, each wearing a lanyard with a name tag with their first name and the name of their group, plus a small radio receiver with a cord to an earphone. Several such groups are walking up and down Via dei Tribunali at any time through the middle of the day.

Piazza San Gaetano has a statue of Napoli's patron saint, known as Saint Cajetan to English speakers. He lived 1480–1547 and was known as a religious reformer and founder of hospitals. He's the patron saint of Napoli in addition to unemployed people, workers, job seekers, and, somewhat incongruously, bankers. The church behind his statue is connected to some really old-time religion.

The Heavenly Twins are young horsemen who served as rescuers and healers in Proto-Indo-European mythology of approximately 4500–2500 BCE, the late Neolithic to early Bronze Age. They were understood to be the sons of the daylight-sky god.

In the Rig Veda, composed in the second millennium BCE in the late Bronze Age, the Heavenly Twins were known as अशिवन् or the Aśvin and they were associated with healing and medicine. In Lithuanian mythology they were the Ašvienai, and the early Latvians knew them as Dieva Dēli. The Greeks knew them as the Διόσκουροι or Dioskouroi, or individually as Castor and Pollux.

The Romans built a temple to the Dioskouroi, the Heavenly Twins, in the first century CE near the center of what now is Via dei Tribunali.

Later, Christian saints were interpreted through the lens of the Neolithic Twin Healers archetype. Cosmas and Damian were third-century Arabian-born twin brothers who embraced Christianity. In the seaport of Aegeae, now Yumurtalık in Adana Province in Turkey, they practised medicine without fees until they were subjected to elaborate martyrdom. Isernia, about 80 kilometers north of Napoli, became one of their cult centers.

Then in the 8th–9th centuries, Chiesa di San Paolo il Maggiore or the Church of Saint Paul the Greater was built on the site of that 1st century Roman temple.

Both the temple and the church were built with their entrances on Via dei Tribunali. The church was built over the temple beyond its prónaos or entryway, so the prónaos and six columns supporting the temple's tympanum stood here until 1688, when a severe earthquake destroyed what remained of the temple. Two of the temple's Corinthian columns were salvaged and now divide the church's façade roughly into thirds.

Thanks to the English, most European accommodations reserved through Booking.com have prominent warnings that any involvement in a "hen or stag party" will lead to immediate eviction without refund.

I saw, but due to the jostling crowds did not have a good opportunity to photograph, multiple groups of young English ladies in tiaras. The central figure of each entourage wore a tiara bearing the word "SPOSA" (Italian for "bride") along with tinsel-wrapped penis-antlers, and she was carrying an inflated crudely-made male sex doll, like Otto the Autopilot in "Airplane". Yes, these were the English "hen parties" of which one reads.

These demure sophisticates were clearly well-versed in classical Greek and Roman culture. Πρίαπος or Priapus was a rustic west Asian fertility god. Greek colonists near Troy worshiped him and took his cult to mainland Greece. From there the cult of Priapus spread to the Greek colonies in Italy during the 3rd century BCE, and he later became a popular figure of Roman erotic art and literature.

Visiting a Mithraic Temple in RomeBy mid-morning the hen parties were marching up and down Via dei Tribunali. They kept it up through the day, transitioning to trudging and then staggering, surrendering by late afternoon to the effects of a full day of drinking, some of it while sitting in the sun. Local shops offered Priapus-inspired phallic drinking vessels filled with limoncello to the visiting Priapus enthusiasts, allowing them to carry his cult to Britain, much as the cult of the Mithraic Mysteries spread to Britain with the Roman soldiers who were sent there.

Complesso Museale Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco, or the Holy Mary Complex of the Souls of Purgatory, is a baroque church founded in the 17th century, dedicated to the souls in Purgatory. It's known to the Neapolitan people as La chiesa de e cape ‘e morte or the Death's Head Church.

Purgatory has parallels to Judaism's Gehenna, Islam's al-A'raf, and Hinduism's Naraka as a sort of Hell Lite™, but Purgatory is a uniquely Roman Catholic concept of post-death suffering for the faithful. An indulgence is some act that can shorten someone's time in Purgatory — the indulgence-obtainer themself, or their suffering dead relative.

Indulgences began around the third century CE, requiring prayer, fasting, or other penance as prescribed by church authorities. By the tenth century, you could get an indulgence by participating in a Crusade. Then, in later Medieval times, indulges were given for pious donations which could be used to fund Crusades and build churches and monasteries. Religious orders along with bishops and archbishops began dealing in indulgences said to wipe out thousands of years of torment in Purgatory. Before Gutenberg famously printed the Bible using moveable metal type in the 1450s, he used the same technology to print standardized indulgence forms, in one case in a run of at least 190,000. Princeton's library has one.

The Avignon PapacyThe English priest and theology professor John Wycliffe (c.1328–1384) criticized numerous church policies and practices, in addition to its wealth. The Black Death had reached England in the summer of 1348. Wycliffe saw it not as God's judgement upon sinful people, but as God's judgement upon an unworthy clergy. 1309–1378 was the period of the Avignon Papacy in which two or three simultaneous Popes competed for power. Wycliffe died of natural causes in 1384, but a later church council decreed that his remains be exhumed, burnt, and the ashes thrown into the river. He was an early figure in what became the Reformation.

Visiting PragueJan Hus led the Bohemian Reformation, he openly condemned the practice of indulgence granting in 1412. Because of that, he was burned at the stake in 1415.

Martin Luther's famous Ninety-five Theses of 1517 criticized indulgences and papal authority. Pope Leo X had raised funds to build Saint Peter's Basilica through indulgence sales. The work of Wycliffe, Hus, and Luther led to the Reformation and Protestantism.

All that led in turn to the Counter-Reformation, under which the more abusive practices related to indulgences were curtailed. But Purgatory remained a Roman Catholic doctrine, defined since 1274, and indulgences were still obtained by participation in special prayers and services.

This church was commissioned in 1616 and consecrated in 1638. It was designed and built on two levels, a Baroque style upper church referring to the earthly dimension, and beneath that a hypogeum representing Purgatory, a burial area for poor people who could not afford a funeral.

The hypogeum is where it gets lurid, with plenty of skull imagery and actual skulls of unknown people. The anonymously buried are considered to be special intermediaries for invocations and intercessions. Local belief is that their spirits have powerful influence over today's life in Napoli. The luridness is increased by English-language explanations that the still-operating Opera Pia Purgatorio ad Arco, which founded this church, is a cult focused on actually worshipping the purganti souls rather than merely honoring them.

Chiesa di Santa Caterina a Formiello or the Church of Saint Catherine (related to a nearby fountain) sits next to a gate through the medieval city wall. The church's construction began about 1510, and was completed in 1593. Its dome is one of the first domes built in Naples.

The interior is in the form of a Latin cross with a single nave with five chapels along each side. It's no basilica, no rows of columns divide the nave from side aisles. There are barrel vaults, half-cylindrical ceilings, over the nave and chapels. The presbytery or chancel, the area around the altar, is square and is also covered by a barrel vault.

This is no Orthodox church, there is no Χριστός Παντοκράτωρ or Khristos Pantokrator, "Christ All-Powerful", within the dome of the crossing.

The fourth chapel on the left side is dedicated to the Blessed Martyrs of Otranto. Tradition says that these were 813 inhabitants of Otranto, in the "heel" of the southern Italian peninsula, who were killed in 1480 after the city fell to an Ottoman army and they refused to convert to Islam. Plus, according to some accounts, another 12,000 killed and 5,000 enslaved but with no demand to convert to Islam.

Tradition continues, saying that a year later the remains of the 813 martyrs were found to be uncorrupted, and they started their journey. First, to Otranto's cathedral. In 1485, remains of 240 of the martyrs were brought to this church. They were moved around various chapels until most ended up under the main altar, where they remain. A few are on display under the altar of this chapel. Above the altar is a 20th century painting depicting their martyrdom.

Food and Drink

Despite the name of my guesthouse, breakfast was not included. No problem: down to the street, two doors down, and breakfast is available. The standard cornetto e doppio caffè. That's a real Italian breakfast. Avoid any place with an English-language sign advertising "English Breakfast", a grotesque assemblage of beans, toast, eggs, beans, sautéed tomatoes and mushrooms, and beans, served with a pot of tea so strong that a spoon can stand erect in it.

Further coffee is available throughout the city.

Why the pictures of Marilyn Monroe in the cafe and not Italian icon Sophia Loren? I don't know.

Then aperitivo time begins in late afternoon. Precisely when? Sono le 17.00 da qualche parte. It's five o'clock somewhere. Perhaps when the hen parties vacate the tables and shuffle off to their accommodations.

Italian aperitivo is like French apéritif — a drink before a meal. Aperol spritz has become extremely popular after a mid-2000s marketing campaign. It's made from Prosecco sparkling white wine, soda water, and Aperol, a somewhat bitter orange liqueur. Or, Limoncello spritz using that lemon liqueur, as I had in the below. Aperitivo includes antipasto or appetizers, sometimes elaborate.

There's the saying about how a snack before a meal will ruin your appetite. Yes, definitely! In Italy, lunch has traditionally been the big meal of the day. Some days I skipped lunch, but if I ate at mid-day and then in late afternoon had an aperitivo, or especially two, I skipped dinner.

Here's an especially nice aperitivo with an Aperol spritz: Smoky provolone curds, buffalo mozzarella, and olives and peppers across the far row; then fava beans flanking bruschetta closer.

Of course the dish to have in Napoli is pizza, which was invented there. Here's a pizza with buffalo mozzarella, just three door down from where I stayed.

It was great, so the same thing at the same place on another evening.

Down to the Port

My plan was to continue down the coast from Napoli to Salerno for a few nights, with a side trip to Paestum. Then I would return to Napoli one afternoon to board an overnight ferry to Palermo, near the northwest tip of Sicily. So, one day I made a scouting trip to the port area, to figure out where I would need to go to board that ferry.

There's one of the large ferries that travel between ports on the Italian peninsula, Sardinia, Sicily, and Tunisia. Beyond it is a gigantic cruise ship. Much smaller fast ferries run between Napoli and Ischia, Capri, Sorrento, and the Amalfitani coast.

Yes, the last Western Roman Emperor used the names of both Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome, and Augustus, the first Emperor. That's just lazy writing.

Napoli has been an important seaport for millennia now. Romulus Augustus, the rather nominal last Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, was deposed by the barbarian general Odoacer in 476 CE. Odoacer allowed Romulus to live because of his "youth and beauty". Odoacer granted Romulus an annual pension similar to the income of a wealthy Roman senator and gave him Castel dell'Ovo, on a small island a short distance from the shore in the Neápolis harbor. It was a paid exile.

And yes, that is Mount Vesuvius you can see across the bay. See my page about Pompeii for more about the continuing danger of that volcano.

Here's the view across the harbor to Vesuvius once I had boarded the ferry. We were still loading trucks onto the ferry for another hour, while there goes a medium-sized ferry headed out of the harbor.

And then my ferry pulled out, headed for Palermo.

Where Next In Italy?

( 🚧 = under construction )

In the late 1990s into the early 2000s I worked on a project to

scan cuneiform tablets

to archive and share 3-D data sets,

providing enhanced visualization to assist reading them.

Localized histogram equalization

to emphasize small-scale 3-D shapes in range maps, and so on.

I worked on the project with Gordon Young,

who was Purdue University's only professor

of archaeology.

Gordon was really smart,

he could read both Sumerian and Akkadian,

and at least some of other ancient languages

written in the cuneiform script.

He told me to go to Italy,

"The further south, the better."

Gordon was right.

Yes, you will very likely arrive in Rome,

but Italy has domestic flights and a fantastic train system

that runs overnight sleepers all the way to

Palermo and Siracusa, near the western and southern corners

of Sicily.

So, these pages are grouped into a south-first order,

as they should be.

The Mesopotamians spoke Sumerian and Akkadian, non-Indo-European languages. They had a pair of divine twins named Lugal-irra and Meslamta-ea. Like the Indo-European twins, they were also associated with the pair of bright stars in the constellation we now call Gemini. Unlike the Indo-European twins, they were warriors rather than healers.