Reconstruction and Dissolution of the Abbey

Glastonbury Rebuilt and Destroyed

We're visiting Glastonbury, supposed home of the legendary King Arthur and his Queen Guinevere, and possibly the Holy Grail. Or possibly the connection to Arthur and Guinevere was wishful thinking by a medieval abbot, and the rest of the mystical theories spun out of that.

The Great Church at Glastonbury was enormous by modern standards. In this picture we are looking down the length from the front toward the rear.

It is very tempting to refer to this as a "cathedral", but that would be sloppy ecclesiastical terminology. A cathedral is the seat of a bishop. Quite literally the seat — a true cathedral will contain a special chair or throne for the bishop. Cathedra is Latin for "chair", so ex cathedra means "from the chair". When there is a formal announcement to be made, the bishop will sit in that chair and speak ex cathedra, from the bishop's chair that leads to the name of the structure.

Jumièges Abbeyin Normandy

A special case of this is the Pope, the Bishop of Rome, who rather infrequently announces formal doctrine for the Roman Catholic church ex cathedra. A special case of this was on 18 July 1870 when Pope Pius IX made a solemn declaration of papal infallibility. File this under "Recursion"...

Papal statements ex cathedra are not frequent. The only big one since 1870 was when Pope Pius XII defined the Assumption of Mary as an article of faith in 1950. A Roman Catholic theologian and church historian compiled a list in 1985 of just 7 ex cathedra documents since 449 AD.

This is simply the abbey's church, or its Great Church in more detail as it is the largest of the churches and chapels in the complex. As for cathedrals, a bishop's church is not necessarily large. The Great Church of Glastonbury Abbey was much larger than many bishops' churches.

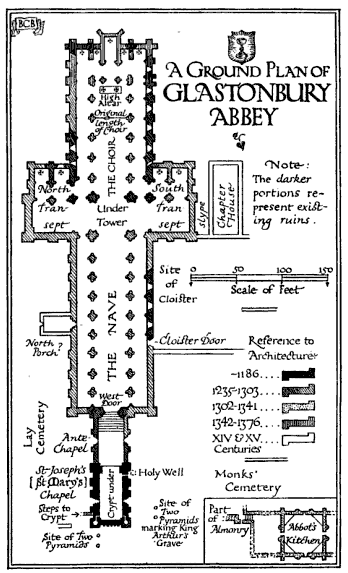

A large church is typically built in the shape of a cross, laid out with the main entry at its west end and the long axis running forward toward the east.

Once inside the church, through the entry doors and possibly having passed through a narthex or vestibule, you enter the largest rectangular area, the nave. That is the furthest visible open area in the views here and below.

The word nave comes from the medieval Latin navis meaning ship. This probably refers to the overhead vaulting's resemblance to a ship's keel and ribs.

Some designs intentionally scaled the nave so its dimensions were proportional to those specified for the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem.

This church's nave was 67 meters (220 feet) long and 14 meters (45 feet) wide.

The crossing is where the north and south transepts or arms of the cross shape intersect the main axis. The bases of the crossing towers are the tallest surviving parts of this church. The transept was 49 meters (160 feet) long side to side or north to south.

Forward of the crossing is the choir, sometimes spelled quire in English. This appeared as an architectural feature as church structures grew and the rise of monasticism provided for a circle of singers or clergy to surround the altar located within the true sanctuary space. The choir was 47 meters (155 feet) long.

In large churches an ambulatory (literally a walking space) passes around the choir and altar area.

The άψίς or apsis (that is, the apse) is the semicircular area at the front. The apse is typically topped with a hemispherical vault forming a semi-dome. That is, a half a dome or a quarter of a sphere.

The πρεσβυτέριος or presbytery is the area around the high altar and is reserved for the clergy. Modern designs usually call this area the chancel. After the doctrine of transubstantiation was introduced in 1215, the division is that the rector maintains the presbytery or chancel while the parish maintains the nave.

In larger churches, especially those of more elaborate French Gothic design, the chevet is a series of apses or small chapels radiating out from the semicircular arc as the ambulatory circles the apse. The word chevet is French for pillow. The idea is that if the plan of the church is a cross, then Christ's head would lie on the "pillow" of the overall layout.

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, elements of which survive mostly unrecognized in western practice, the north and south sides of the apse have special significance. In small chapels these may just be the two sides of the space beyond the iconostatis, but in larger churches there may be a triple apse, the central one typically larger than the two to its sides. Tripsidal is the formal term for having three arches.

Ground plan of the Great Church built after 1184, from Wells and Glastonbury, a Historical and Topographical Account of the Cities.

The south apse is the Διακονικόν in Greek or Диаконик in Church Slavonic, or the Diaconicon. In English practice it is called the sacristy. It's a chamber where the vestments and books used in the services are stored in cabinets. It usually contains a θαλασσιδιον or писина, a sink draining into "an honorable place in the ground" where the clergy wash their hands before serving the Divine Liturgy and where water used to wash the vestments and sacred vessels may be poured. The idea is that the water was used sacramentally and now is returned directly to the earth. The piscina or thalassidion was rarely found in English churches before the 13th century, after which it became nearly universal, typically as a pair of basins in a double niche beside the altar.

The north apse is the Προθέσις in Greek or the Протезис or Жертвенник in Church Slavonic, or the Prothesis or Zhertvennik. It has the small Table of Oblation on which the bread and wine are prepared for Divine Liturgy. It was originally just a smaller table placed against the wall to the north of the altar, but in the 500s it came to occupy a chamber of its own, having a separate apse connecting to the altar area through an arched opening.

A tour at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York explained that large churches typically have two lecterns at either side of the choir area, with the Old Testament reading done at the one on the south side and the New Testament on the north side. One interpretation of this is that the tradition dates from when Christianity was limited to southern Europe. Pope Celestine III called for a crusade against the pagans of northern Europe in 1193, with Estonia finally being forcibly Christianized in the 13th century. The idea of arranging the components of this service is that it enacted "bringing the gospel to the pagan north."

Of course, the results of forcible crusades are not always what one might hope for. Today's Estonia is one of the least religious countries in Europe, even less religious than the Netherlands. The explanation that makes sense to me based on what I've seen is that up through the late 1800s religion was part of the heavily oppressive Germanic feudal rule of Estonia. And then almost immediately after that they were controlled by the Russians, which happened to quickly turn into the Soviets, in which religion became something for which you were punished.

Given their history over the past few centuries, in which religion was a source or cause of suppression, I would be surprised if the Estonians were religious at all.

The Lady Chapel is the one dedicated to the Virgin Mary. It typically has a prominent location, often at the very center of the apse, in the chevet. The Lady Chapel at Glastonbury is instead in the crypt below the rear of the nave. This is because it was built on what was believed to be the location of the Vetusta Ecclesia, the mud and wattle Old Church believed at that time to have been built by Joseph of Arimathea. A nave was later built over the Lady Chapel, making it into a subterranean crypt. This stacked pair of chapels was 53 feet long by 24 feet wide in the lower level, wider above.

After the great fire of 1184 the great church was built to the east of this relatively small two-level church. Then an ante-chapel was built, connecting what eventually became the Chapel of Saint Joseph of Arimathea with the Lady Chapel below to the west door leading into the nave of the great church. The monks intentionally incorporated antiquated design elements to give the church the appearance of greater age.

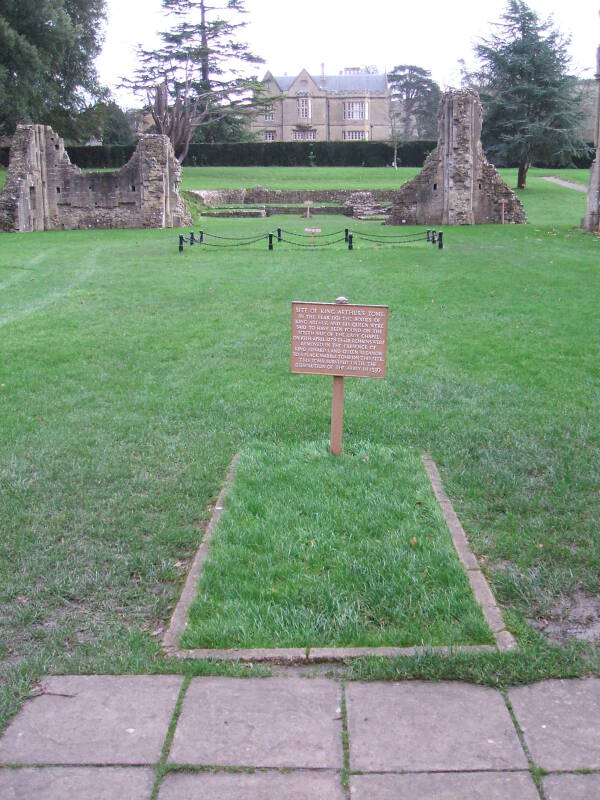

In 1278 the remains of King Arthur and Guinevere were reburied near the High Altar in the Great Church. Here we're looking over their new grave toward the site of the High Altar within the chains. The sign says:

Westminster Abbey in London was the only abbey more wealthy than Glastonbury during the 14th century.

Here we have turned to look back from the altar. That's the supposed second tomb of Arthur and Guinevere toward the rear of the choir area, then the towers of the crossing which hide the remaining walls of the nave. The arch in the distance leads from the rear of the nave into the ante-chapel and then into the Chapel of Saint Joseph of Arimathea above the Lady Chapel.

The nave was 220 feet long, 80 feet wide in total and 40 feet between the piers.

The transept was 160 feet long, with two chapels on the front or east wall of each arm.

With the ante-chapel or Galilee joining the west door of the nave to the originally freestanding chapel of the Virgin Mary, all of this added up to a total length of five hundred feet.

The cloister was against the south wall of the nave and the west all of the south transept, enclosing an area 220 by 491 feet. The chapter-house was beside the south transept.

A letter written in September of 1705 said that some of the abbot's apartments had recently been taken down. In April of 1716 it was recorded that no marks of the cloister remained visible. The ruins were used as a quarry through the 1700s.

The monks slept in dormitories south of the Great Church and cloister and within the abbey complex, which was surrounded by a protective wall. The walls enclosed an area of about 36 acres or 14.5 hectares.

The dorter was the monks' dormitory in medieval monasteries.

The reredorter or necessarium was an attached communal latrine.

The Middle English prefix rere- comes from the Anglo-French introduced by the Normans, meaning backward or behind, from the Latin retro. Combined with the archaic term dorter it forms reredorter.

However, the word reredorter is a recent invention, constructed in the 19th century. The monks who lived here would have called it their necessarium or place of necessity.

You see, the monks throughout the centuries were comfortable calling it their necessarium. But even that Latin circumlocution was too direct and vulgar for the Victorians, who obligated themselves to further obscure the concept by calling it a reredorter.

A reredorter or really a necessarium was typically built with a row of seats on the first floor of the dormitory building. Waste fell just inside the lower wall into a channel to be carried away by water.

Above and below you see one of the reredorters still visible at Glastonbury Abbey.

See my Toilets of the World site for more on Arthurian and other historical necessaria and other toiletological details, with no Victorian squeamishness standing in the way.

The Abbot of Glastonbury maintained a fantastic home, right up until the sudden and horribly violent end of that position. More on that in a moment...

The abbot's kitchen is the only monastic building surviving at Glastonbury Abbey, and is one of the best preserved medieval kitchens in Europe. What we see today was built by Abbot John de Breynton, who held the office 1334-1342. It was a huge affair, forty feet square with an extremely large fireplace at each corner. There is a smoke outlet above each of them, and another at the center of the pyramidal roof.

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries (described below) and the passage of the Abbey into private ownership, the kitchen became a Quaker meeting house and thereby survived disassembly and reuse.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, also called the Suppression of the Monasteries, was at its core a series of administrative and legal processes during the short period of 1536 through 1542. Its origins, however, cover the preceding two centuries.

The Norman Conquest of 1066 had led to French religious orders holding substantial properties in England. After 1378 these priories dependent upon French monasteries maintained allegiance to the Avignon Papacy, with the rival Roman Popes supporting their suppression and the confiscation of their monastic properties. Some were confiscated and their estates typically transferred to educational organizations, mostly new colleges at Oxford and Cambridge.

In 1521 Martin Luther, himself a former Augustinian friar, published De votis monasticis or On the monastic vows, declaring that the existing monastic life in Europe had no scriptural basis, was pointless and also actively immoral, and was not compatible with the true spirit of Christianity. He said that monastic vows were meaningless and no one should feel bound by them.

In 1527 King Gustavus Vasa of Sweden secured an edict of the national Diet allowing him to confiscate all monastic lands he deemed necessary to increase royal revenues, with properties previously donated to the church returned to the descendants of the donors. This was a very shrewd move, he simultaneously gained a large collection of estates and a large body of thankful supporters.

King Frederick I of Denmark followed suit in 1528.

It had become standard practice in Western Europe since the 12th century for the household expenses of abbots and the conventual priors to be separated from those of the rest of the monastery. The expenses for the abbot's household were typically over half of the total for the monastery. As Orwell explained, the commandments quickly compress to "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others."

The pope approved of a plan in which these funds would be diverted upon the vacancy of a position to a non-monastic ecclesiastic, meaning that about 80% of French abbacies soon came to be held by lay courtiers or royal supporters, all of this with the pope's blessing. The Scottish kings quickly saw what was going on and followed suit. The English government and especially Thomas Cromwell, soon to become Henry VIII's chief minister, also noticed the trend.

Thomas Cromwell was born in Surrey in 1485. As a youth he crossed the Channel to the continent. It is said that "accounts of his activities in France, Italy and the Low Countries are sketchy and contradictory." He seems to have become a mercenary and marched with the French army to Italy, fighting in the battle of Garigliano in December, 1503. Once in Italy, he entered the household of the Florentine merchant banker Francesco Frescobaldi. After that he lived among the English merchants in the leading mercantile centers in the Low Countries, learning several languages and amassing an important network of contacts. He seems to have returned to Italy for a while, then returned to England. By 1523 he had a seat in the House of Commons. By late 1529 he had a search in Parliament as a member for Taunton, and during the last weeks of 1530 the King appointed him to the Privy Council.

Henry VIII had been struggling since 1527 to have his marriage to Queen Catherine annulled so he could marry Anne Boleyn. All of this came down to the question of who was really in charge — the secular, temporal King, or the sacred authority of the Pope?

In February 1531 Henry had himself declared Supreme Head of the Church in England.

All the King's men (and their horses!) were working on the problem of Henry versus Pope, but by January of 1533 Anne Boleyn was pregnant and matters were now extremely urgent. There was a secret wedding. It's unclear just when or where, but Parliament was recalled to pass the needed laws to make it all legal. In April 1533 an Act in Restraint of Appeals eliminated the clergy's right to appeal over the King's head in any spiritual or financial matter to "foreign tribunals", meaning Rome. The Submission of the Clergy declared that the King was, and always had been, the Supreme Head of the Church in England.

The Pope was not happy with an English king doing as he pleased, so in December of 1533 Cromwell was assigned the task of discrediting the papacy.

There were sermons, pamphlets, and then Parliament was again summoned to pass legislation needed to formally break the remaining ties to Rome. In April 1534, Thomas Cromwell was confirmed as the principal secretary and chief minister to Henry VIII.

By 1536 Henry had executed Anne, basically for failing to provide male offspring although it was wrapped in more complicated explanations including high treason, incest and adultery, and he had married Jane Seymour. No, not from the James Bond movie or the TV show, but the maid-of-honor to the former Queen Catherine. Well, you can't complain that she couldn't have seen that something bad was probably coming.

Parliament enacted the Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries Act in early 1536, seizing a number of smaller monasteries.

Through the end of the summer of 1537 it became clear that Henry's real objective was not the supposed reform of monasticism in England and Wales, but its total eradication. There had been over 800 monasteries, nunneries and friaries in England in 1536. By 1541, there were none. Over 15,000 monks and nuns had been run off and their buildings seized by the Crown.

Jane Seymour died about a week after the birth of a son (finally!), Edward, on 12 October 1537. Cromwell immediately set out to fix up his King with another wife, leading him to push very hard for Anne of Cleves, the sister of the Duke of Cleves and therefore an important potential Continental ally.

While Thomas Cromwell was still in power (that is, before Henry saw Anne in person), his minions visited Glastonbury Abbey in September, 1539. The Abbey was shortly stripped of its valuable possessions, including the supposed skeletons of Arthur and Guinevere and the inscribed lead cross. Its abbot, Richard Whyting, and two monks, John Thorne and Roger James, were executed by hanging after being accused of being traitors against the Crown on 15 November 1539. The abbot was then beheaded, drawn and quartered. His head was placed on the abbey gate, and the four sections of his body were distributed to Wells, Bath, Ilchester and Bridgewater.

Henry recklessly agreed to Cromwell's suggestion of marriage to Anne of Cleves, based on what seems to have been her fictional portrayal by Hans Holbein the Younger. Anne arrived in Dover toward the end of December, and Henry met her at Rochester on New Year's Day of 1540. As the English royals tend to say, "We are not amused." Anne seems to have been a fright. They went through the formal motions of a wedding ceremony in Greenwich on 6 January, but Henry couldn't bring himself to consummate the marriage.

Henry granted Cromwell the earldom of Essex and the senior court office of Lord Great Chamberlain, but Cromwell's time of royal favor was over. As Henry VIII famously said, "Worst. Wingman. EVER."

Cromwell's conservative opponents used the King's anger at being forced to marry Anne of Cleves as leverage to topple him.

Thomas Cromwell was condemned to death without trial and beheaded on Tower Hill on 28 July 1540. Yeah, Anne of Cleves was that ugly. It was the same day that Henry VIII married Catherine Howard, having annulled his marriage to Anne of Cleves. Cromwell's head was set on a spike on London Bridge, foreshadowing the treatment of his sister's great-great-grandson Oliver Cromwell in 1658.

Once things settled down, it appeared that the Dissolution of the Monasteries had enriched the Crown to the tune of £150,000 per year, or £63,606,300 in 2013 value.

The abbeys of England, Wales and Ireland had been the largest landowners and the largest institutions. They had been the centers of hospitality and learning, and a main source of charity for the old and infirm. The Act of 1539 also suppressed the religious hospitals which had been created for the purpose of caring for older people. Most of them were simply closed with small pensions given to their former residents.

Monasteries had also supplied free food and alms to the poor and destitute. The removal of this support, amounting to about 5% of net monastic income, is often cited as a factor in creating "the army of sturdy beggars" that plagued late Tudor England, causing the social instability leading to the Edwardian and Elizabethan Poor Laws.

Meanwhile, the destruction of the monastic libraries probably was the greatest cultural loss of the English Reformation. The Glastonbury Abbey's library was described by John Leland, a visiting antiquary of King Henry VIII, as containing unique copies of ancient histories of England and unique early Christian documents. Although it was affected by the fire in 1184, it still housed a remarkable collection until 1539.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries had little effect on English parish church activity. Parishes that had been paying their tithes to a monastic house now paid those same tithes to a lay figure. Meanwhile the rectors, vicars and others remained in place, their duties and incomes unchanged. For those congregations that had shared monastic churches for worship they continued to do so, but the formerly monastic parts were walled off and became derelict.

In northern England, especially in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, the suppression of the monasteries led to the "Pilgrimage of Grace", a popular uprising that threatened the Crown for a number of weeks. Rumors circulated, saying that the King would strip the parish churches and even tax the sheep and cattle. Henry solemnly promised to do none of these things and settled the uprising. Then he summarily executed its leaders.

The Glastonbury abbey's ruins were sold to a local family, eventually created as the Marquesses of Bath. They stripped the ruins of the lead roofing and dressed stones, those being hauled away for use in other buildings.

The site was granted by Edward VI (ruled 1547-1553) to Edward Seymour, the 1st Duke of Somerset, who established a colony of Protestant Dutch weavers on the site. It was then granted by the crown to private ownership in 1559, lasting until the early 20th century. During that time further stones were removed so that it was described as a ruin by the early 18th century.

Gunpowder charges were used to further dislodge stones in the early 19th century as the site continued to serve as a crude quarry. Finally, in 1882, the Ancient Monuments Protection Act ended the continuing damage to the site.

The Bath and Wells Diocesan Trust purchased the site in 1908. They appointed Frederick Bligh Bond to lead an archaeological study of the site. But he was dismissed in 1921 because of his use of seances and psychic archaeology to "investigate" the site.

And with seances and psychic archaeology we come to modern-day Glastonbury, but first, some background on the legends of: