National Security Agency Museum

NSA Museum

These are some pictures I took during a visit to the National Security Agency's museum. Yes, the NSA has a museum that is open to the public. It's located in what used to be a small motel at the expressway interchange closest to the main entrance to the NSA. The NSA operated the motel to provide a convenient place for off-site meetings. If you happened to stop and ask for a room, they were always full or so they said. For more details on the museum, see the NSA's pages.

Here we see a Sturgeon German cipher machine. Sturgeon was the code name assigned by British cryptanalysts, the original name was the Siemens and Halske T52, or the Geheimfernschreiber ("secret teleprinter") or Schlüsselfernschreibmaschine (SFM).

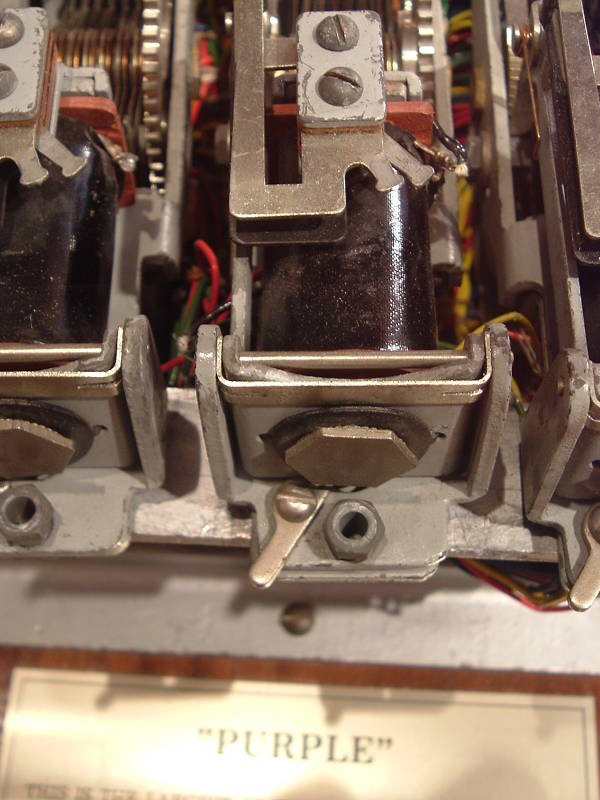

To the right of that is a fragment of a Purple Japanese cipher machine, the only known one in existance.

"Purple" was a code name used by the United State cryptanalysis effort, based on the color of the binders used to collect and organize material from this system.

Cryptanalysisand the

Nuclear Bomb

The Japanese name was 97-shiki ōbun inji-ki, or System 97 Printing Machine for European Characters. The designation "System 97" referred to its design being completed in 1937, which was year 2597 in the Japanese imperial calendar. It was also known as the Angōki Taipu-B or Type B Cipher Machine.

Japanese diplomatic codes had been broken for some time, including during the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty meeting. See my page on the New York sites of the American Black Chamber for more on that. The Japanese learned about the insecurity of their systems, and developed a series of systems through the 1920s and 1930s. That led to a system known to the U.S. as Red, followed by Purple.

Purple was an electromechanical system based on stepping switches similar to those used in telephone switching systems. It inherited a cryptographic weakness from the preceding Red system, in which vowels (AEIOUY) were enciphered separately from the consonants. This characteristic was called "sixes-twenties" by the U.S. Army's Signals Intelligence Service.

The resulting Purple design was potentially quite secure, but the Japanese committed key management and other operation errors similar to those made by the Germans with their Enigma system. For example, the Japanese divided each month into three 10-day periods. They started each 10-day period with a key for that day, and then made only small predictable changes to the keys used for the remaining nine days. That provided ten times the material for what was basically the same key information, and it meant that breaking a key for one day really provided the keys for that 10-day block.

"Purple" was a code name used by the United State cryptanalysis effort, based on the color of the binders used to collect and organize material from this system.

The Japanese name was 97-shiki ōbun inji-ki, or System 97 Printing Machine for European Characters. The designation "System 97" referred to its design being completed in 1937, which was year 2597 in the Japanese imperial calendar. It was also known as the Angōki Taipu-B or Type B Cipher Machine.

See my page on the Japanese diplomatic codes had been broken for some time, including during the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty meeting. New York sites of the American Black Chamber for more on that. The Japanese learned about the insecurity of their systems, and developed a series of systems through the 1920s and 1930s. That led to a system known to the U.S. as Red, followed by Purple.

Purple was an electromechanical system based on stepping switches similar to those used in telephone switching systems. It inherited a cryptographic weakness from the preceding Red system, in which vowels (AEIOUY) were enciphered separately from the consonants. This characteristic was called "sixes-twenties" by the U.S. Army's Signals Intelligence Service.

The resulting Purple design was potentially quite secure, but the Japanese committed key management and other operation errors similar to those made by the Germans with their Enigma system. For example, the Japanese divided each month into three 10-day periods. They started each 10-day period with a key for that day, and then made only small predictable changes to the keys used for the remaining nine days. That provided ten times the material for what was basically the same key information, and it meant that breaking a key for one day really provided the keys for that 10-day block.

The U.S. Army's Signals Intelligence Service, directed by William Friedman, broke Purple in 1940. They had constructed an equivalent machine, their own electromechanical system with the same ciphering and deciphering characteristics.

This fragment was recovered from the Japanese Embassy in Berlin immediately following Germany's defeat in 1945.

Apparently all other Purple cipher machines at Japanese embassies and consulates around the world, as well as all those in Japan itself, were completely destroyed by the Japanese. The American occupation forces in Japan in 1945-1952 searched thoroughly but found no other units.

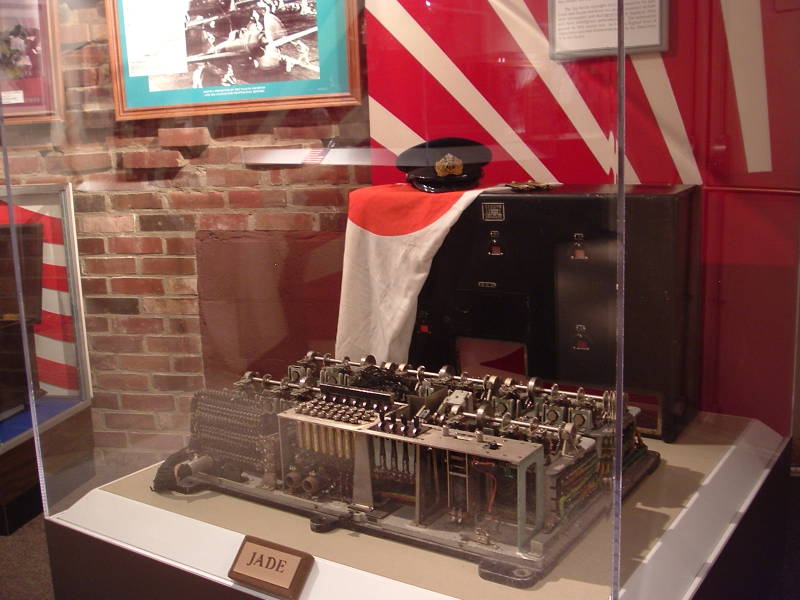

This is the only known surviving Jade Japanese cipher machine. The Jade design was used by the Imperial Japanese Navy from late 1942 until 1944. It enciphered messages in katakana using a set of 50 symbols.

Below is a World War II Allied Type X cipher machine.

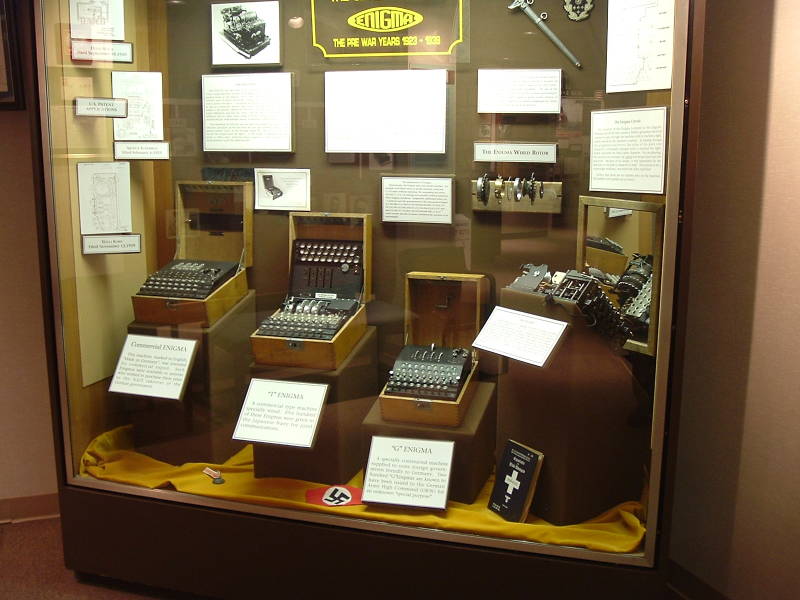

They have a collection of Enigma machines on display.

At the left in the above picture is a Luftwaffe (Air Force) unit.

Next to that is a case holding seven rotors.

An Army Enigma is in the center, and a small radio is on the high post next to it.

A Kriegsmarine (Navy) unit with four rotors is at far right.

Below is another collection of Enigma machines.

A commercial Enigma is at far left.

The next unit is a "T" Enigma, a modified commercial unit. Five hundred of these were given to the Japanese Navy for joint communications.

The "T" unit has its cover open, as if to change rotors or rotor settings.

The third is a "G" Enigma, a specially modified four-rotor system supplied to some foreign governments friendly to Nazi Germany.

At far right is an Enigma with its case removed, to show its internal workings, and above that, a disassembled rotor.

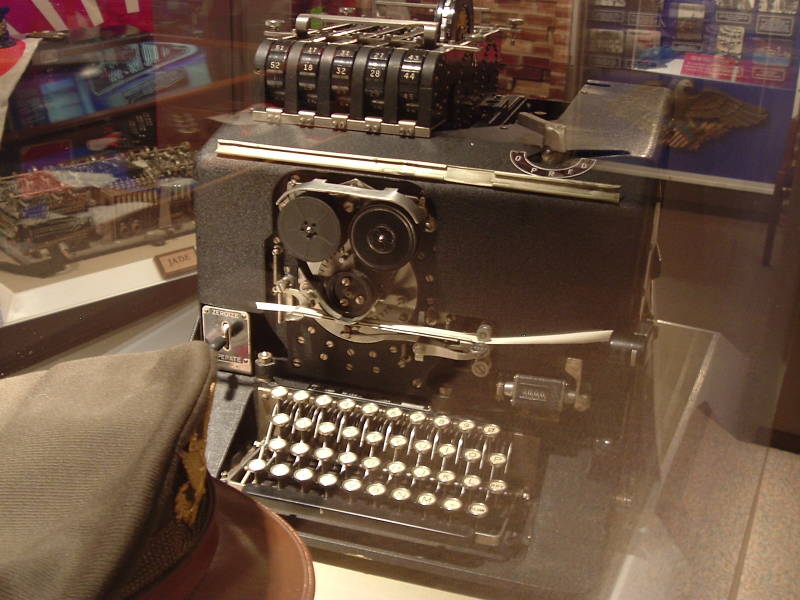

Here is a close-up of one four-rotor Enigma machine. The Enigmas had, of course, a European keyboard layout:

Q W E R T Z U I O A S D F G H J K P Y X C V B N M L

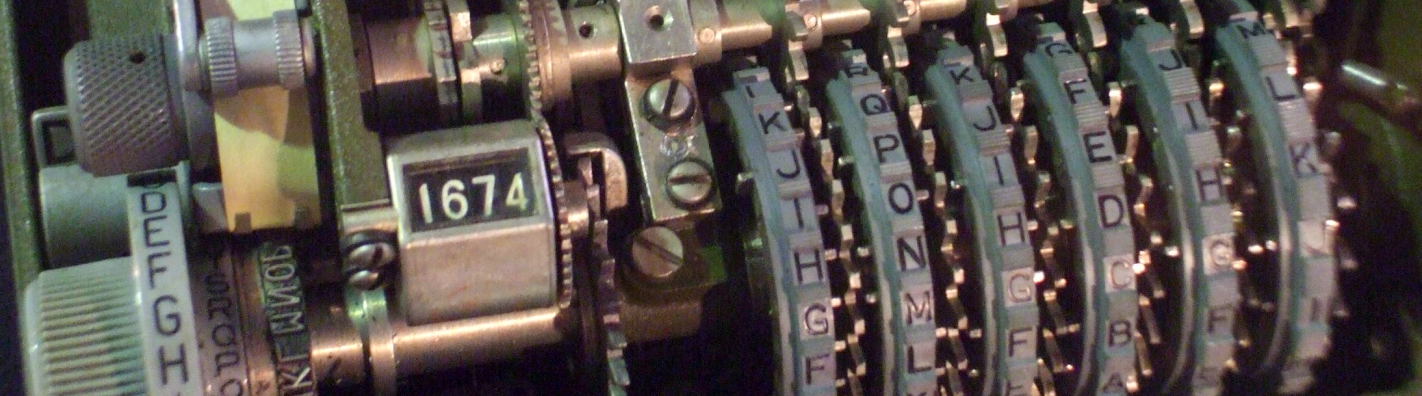

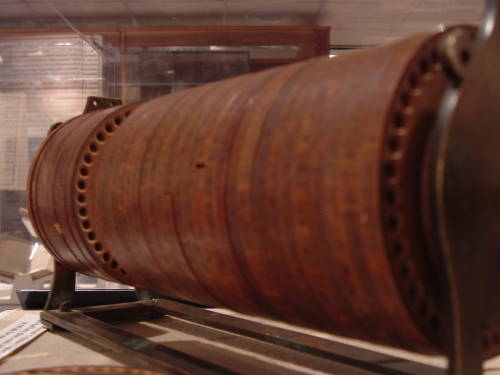

Thomas Jefferson invented what he called his Wheel Cypher in 1795. Is this actually his? Or just one built to the same design from the same time? They're not sure...

Jefferson's design consists of 26 discs, each with the 26 letters of the English alphabet printed in a random order around its exterior rim. Each user of the system needs an identical set of 26 discs.

The key for the system is the order in which the discs are placed on an axle.

With the disc set "keyed", the sender rotates the discs as needed to spell out the message along one row visible down the side of the cylinder. The sender then selects any other row as the outgoing ciphertext.

The receiver similarly "keys" a stack of discs, and rotates them as needed to spell out the ciphertext. It is then a matter of examining the other 25 rows spells down the cylinder's length to find one containing plausible plaintext.

Here is a simple Unix script to generate a random ordering of the 26 English letters:

#!/bin/sh

# Make /tmp/list an empty file.

rm -f /tmp/list

touch /tmp/list

# Each line gets a random hexadecimal string and a letter.

for L in A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

do

VAL=`dd if=/dev/urandom bs=1 count=2 2> /dev/null |

od -x |

awk 'NR == 1 {print $2}'`

echo "$VAL $L" >> /tmp/list

done

# Sort that list into its random order and print the letters.

sort /tmp/list | awk '{printf("%s", $2);}'

echo ""

Let's use that to generate a simpler 12-disc system:

Disc 1: VQNYZMIOSBRFXGPEAWCUTDKLJH Disc 2: JHDETUOMPFBKZNXVARGCWYLSIQ Disc 3: GJDYPOHRTMNVBFIQSKUXLWECZA Disc 4: UGZPQJFVLTKSCIDHANEROXWMBY Disc 5: UNTAZJLWYPBFVSIQEOGMCRXDKH Disc 6: HFMEXKOLPWAYCGJISRNBZDUVQT Disc 7: POZJWEXILCYNBGSFHADTRVKMUQ Disc 8: YSTFIWHJDALOBQNUECKXMGPZRV Disc 9: NSIXJAELYTDFCVRMGUZOBWQHPK Disc 10: LVEIKUBTZHGXOSRYCNQAMJWFDP Disc 11: UFZJKSTPYECQRABVIXNLOWHDGM Disc 12: XAEQTYWDCKHNPJLGIOMZURBSVF

Let's say that today's key is:

11, 1, 5, 4, 2, 8, 6, 10, 7, 12, 3, 9,

and we want to send the classic example message

ATTACK AT DAWN.

The sender keys the system by ordering the discs on the axle.

The rows here represent the edges of the discs, so the columns

in this table correspond to rows on the resulting cylinder:

Disc 11: UFZJKSTPYECQRABVIXNLOWHDGM Disc 1: VQNYZMIOSBRFXGPEAWCUTDKLJH Disc 5: UNTAZJLWYPBFVSIQEOGMCRXDKH Disc 4: UGZPQJFVLTKSCIDHANEROXWMBY Disc 2: JHDETUOMPFBKZNXVARGCWYLSIQ Disc 8: YSTFIWHJDALOBQNUECKXMGPZRV Disc 6: HFMEXKOLPWAYCGJISRNBZDUVQT Disc 10: LVEIKUBTZHGXOSRYCNQAMJWFDP Disc 7: POZJWEXILCYNBGSFHADTRVKMUQ Disc 12: XAEQTYWDCKHNPJLGIOMZURBSVF Disc 3: GJDYPOHRTMNVBFIQSKUXLWECZA Disc 9:NSIXJAELYTDFCVRMGUZOBWQHPK

The sender enters the cleartext by rotating the discs:

Disc 11: LOWHDGMUFZJKSTPYECQRABVIXN Disc 1: VQNYZMIOSBRFXGPEAWCUTDKLJH Disc 5: YPBFVSIQEOGMCRXDKHUNTAZJLW Disc 4: WMBYUGZPQJFVLTKSCIDHANEROX Disc 2: QJHDETUOMPFBKZNXVARGCWYLSI Disc 8: RVYSTFIWHJDALOBQNUECKXMGPZ Disc 6: SRNBZDUVQTHFMEXKOLPWAYCGJI Disc 10: SRYCNQAMJWFDPLVEIKUBTZHGXO Disc 7: UQPOZJWEXILCYNBGSFHADTRVKM Disc 12: DCKHNPJLGIOMZURBSVFXAEQTYW Disc 3: JDYPOHRTMNVBFIQSKUXLWECZAG Disc 9: ELYTDFCVRMGUZOBWQHPKNSIXJA

The ciphertext is then any one of the other 25 rows on the

cylinder, which would be the columns in the above table.

For example:

LVYWQRSSUDJE,

or OQPMJVRRQCDL,

or WNBBHYNYPKYY,

or HYFYDSBCOHPT,

and so on.

The receiver keys the system by stacking the discs,

rotates them to enter the received ciphertext, and

finds the meaningful line among the other 25.

Jefferson invented this in 1795. It did not become well known, and it was independently reinvented about a hundred years later by Etienne Bazeries. It was used as the M-94 device by the United States Army, Navy, Coast Guard, and the Radio Intelligence Division of the FCC from 1922 through 1942 (the Navy called it the CSP 488).

A version based on sliding paper strips rather than discs was known as the M-138-A cipher device and was used from the 1930s through the end of World War II in 1945. Click here to see an M-138-A at the Historical Electronics Museum outside BWI airport near NSA headquarters.

This is a US Navy cryptanalytic bombe.

The "bombes" were parallel simulators of multiple cipher systems in slightly different key settings, used to search for keys.

Compare this to the reconstructed bombes at Bletchley Park in England.

This EA-3 used for SIGINT missions is in the small air museum between the museum and the main headquarters.

Some of main NSA headquarters buildings are visible in the background.

This EC-130 was used for SIGINT missions.

Foreground: Beechcraft used for SIGINT missions in Vietnam.

Background: EC-130 used for SIGINT missions.

That's it for my visit. For more details see the NSA's pages.