Dolmen de la Pitchoune

A Megalithic Dolmen structure in Provence, in southern France

When you think about visiting Provence, a beautiful region in southern France, you think of wine and cheese in picturesque villages. If you do think about history, it is probably limited to the past century, or possibly to the Romans who built roads and bridges in the countryside and larger structures like the amphitheatre in Arles or the water-powered factory in Barbégal. You don't usually think about the late Stone Age and megaliths. However, you can easily find mysterious prehistoric ruins in the countryside of Provence.

France has been occupied for a long time. Its occupants began building megalithic structures and monuments back in the Neolithic (late Stone Age) and Chalcolithic (or Copper Age), over the period from about 4800 BC to 1200 BC.

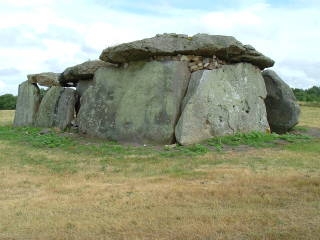

Megalithic structures take a variety of forms. The dolmen is a common one — a large flat capstone forming a roof over an enclosed space. The capstone may be supported by large upright stone pillars or panels.

Provence has a long history of human occupation. Primitive stone tools dated to 1 to 1.05 million years ago have been found in caves along the coast between Monaco and Menton, along with more recent but still Paleolithic tools from 600,000 years ago to 10,000 BC at other sites along the French Riviera coast. See my page on visiting Marseille for more about tools and paintings found in caves with openings now submerged below the level of the Mediterranean.

Map of the development of megalithic architecture in Stone Age Europe.

In the area around the lower Rhone River, part of today's Provence area, the megalithic builders were active early. Megaliths in this area date back to 4800 to 3000 BC, as shown by the orange areas on this map. The yellow areas were active later, from 3000 to 1200 BC.

The Chasséen culture arrived in the region around 4500 BC and lasted until 3500 BC. The Chasséen culture spread throughout today's France, through Seine and Loire river regions, from Pas-de-Calais in the north down through the Vaucluse in the south. They were farmers of rye, panic grass, millet, apples, pears, and prunes, and herders of sheep, goats, and oxen. They formed small villages of 100 to 400 people and lived in small huts. They were adept Neolithic workers of flint, metal technology had not yet been developed.

The Dolmen de la Pitchoune is near the Provençal village of Ménerbes, north of Marseille and southeast of Avignon, in the Luberon area. Pitchoune comes from the Provençal word pitchouno, meaning little girl. Members of this Chasséen culture may have built this dolmen.

A side street in Ménerbes.

The main street through Ménerbes at the center of town.

The rural areas of the Vaucluse département were poor and growing poorer through much of the 20th century. The population of the town of Ménerbes dropped from over 1400 in the 1800s to just over 900 in the 1920s and 830 to 850 in the 1930s. Cheap holidays became available after World War II. By 1960 the village of Ménerbes had become half depopulated, although some notable members of the artistic community came to visit one of Picasso's models and a French diplomat, both of whom maintained homes in the area. The population stayed below 900 in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Then British author Peter Mayle made the village of Ménerbes famous in his books, starting with A Year in Provence. Mayle's first book was a hit, and he followed it with more. His books about his life in the area brought about a huge turnaround in the local economy, with many foreign tourists visiting during the high season.

Amazon

ASIN: 0679731148

Amazon

ASIN: 0679736042

Things had been quiet before that. The town's name comes from the Roman goddess Minerva, and texts from 1081 refer to the village as Menerba and also as Minerbium, so there was a settlement here but it was mostly a very quiet one.

Wars ofReligion

The big excitement came during the French Wars of Religion, when a group of Protestants comprising some 150 soldiers and followers established a stronghold in the walled town of Ménerbes in a successful bid to intentionally antagonize Pope Pius V.

The Siege de Ménerbes lasted five years and two months, from 1573 to 1578. The Pope's forces, led by Henri d'Angoulême, surrounded the walls of Ménerbes with trenches and then fired 14 tons of lead bullets plus 900 cannonballs and incendiary rounds into the town over the years. The Protestant forces finally surrendered in December 1578, with the cost for the artillery and supporting forces having strained papal finances.

Above is the Provençal countryside as seen from the edge of Ménerbes. The Dolmen de la Pitchoune is just a few kilometers from the village, off to the right of this view.

Ménerbes is in the southern département of Vaucluse, east of Avignon and north of Marseille. It is marked with a red circle in this map.

Looking closer, Ménerbes is about the last village as the road partly ascends the steep northern slopes of the Montagne du Luberon ridgeline. Lacoste, Bonnieux, and other scenic villages are very close.

There are so many monuments mégalithiques in France that Michelin has a symbol for them on their excellent maps. It is shaped like a stereotypical dolmen and it looks a little like the Greek letter π.

You exit the village of Ménerbes down a steep hill to the east. See the V-shaped symbol for a steep uphill grade on the map at left. At the road intersection at the bottom of the hill, marked by the red stick and ball mileage endpoint symbol, take the smaller D 103 to the southeast for just about a kilometer, toward Les Moutins.

Amazon

ASIN: 2067133861

The dolmen is along the D 103 road on its left-hand side as you're driving away from Ménerbes. Get the Michelin map for all the details.

There is a sign along the road at the Dolmen de la Pitchoune. Without the sign, the dolmen would be difficult to see.

The dolmen is nearly covered by the road and its embankment. Driving down the road you appear to cross a short bridge. It's really a retaining wall used to keep the road off the dolmen.

That's me standing on the dolmen's capstone — I told you that it was close to the road!

Looking down from the edge of the road, you see the capstone and the supporting walls. The dolmen's entryway is almost against the road's retaining wall.

Unlike many dolmens with megalithic support walls, especially those in Brittany and Britain, the Dolmen de la Pitchoune has side walls of stacked drystone construction.

I'm down in the dolmen investigating the interior.

In the interior you see the stacked drystone side walls and the megalithic rear wall.

The chamber is 2.9 meters long, 1.9 meters wide, with a height from the stone floor of about 1.75 meters.

It was rediscovered around 1850 by a farmer who dug out its contents to store his potato crop. The Ménerbes village priest later studied it and reported it to the Archaeological Society of France.

That organization seems to have forgotten about it. The dolmen was rediscovered again in 1909 by André Moirenc, a road inspector and amateur archaeologist who lived nearby in Bonnieux. He carried out some excavations yielding a few bones and flint.

Further excavations were made here in 1972 by Gerard Sauzade. The dolmen itself had been emptied to turn it into a potato cellar and so there was nothing to find there. Sauzade processed the old excavation tailings with fine screens and collected several bones, some teeth, a flint arrowhead, two limestone beads, and fragments of pottery.

The capstone is a large single stone estimated to weigh about six tons.

The view from the dolmen's entrance once looked across the valley to the row of hills to the south. Now you have to be up on the capstone roof to see over the D 103 road. The entryway of the dolmen would have connected to a short corridor, its location now obliterated by the road.

Megaliths in France