Saint-Denis, the Burial Place of French Kings

Basilique royale de Saint-Denis, the Royal Necropolis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (or Basilique royale de Saint-Denis) is a large abbey church in what now is a northern suburb of Paris. It's a short walk from the next-to-last stop on the Métro Line 12, so it's an easy place to visit.

There was a Gallo-Roman cemetery here in late Roman times, and a Christian monastery and church were built here around 475. In 636 the relics of Saint Denis, a patron saint of France, were moved here, and the church became a pilgrimage site.

The abbot of the associated monastery rebuilt parts of the abbey church in the 12th century. His architects used some new structural and decorative features. The result is considered to be the original Gothic building. It became the model for medieval cathedrals and abbeys across northern France, England, and Germany, and the Gothic style spread from there.

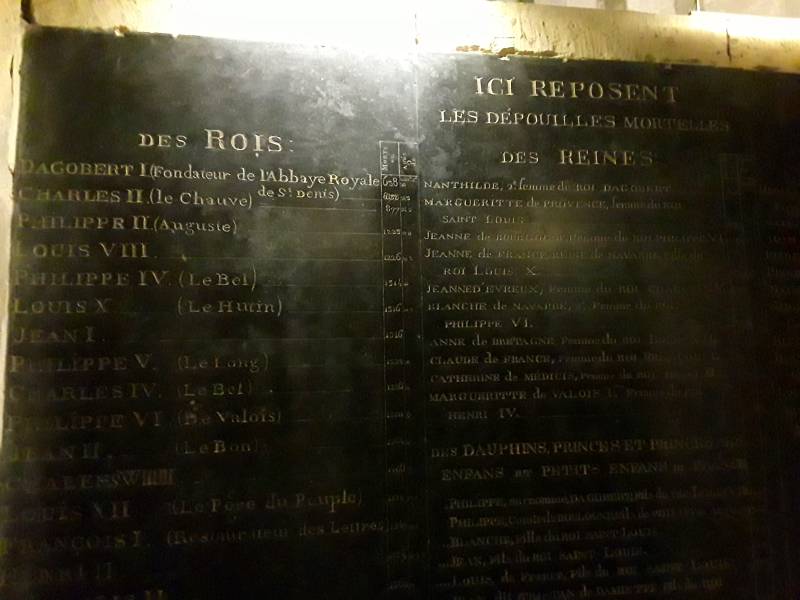

The church became the burial place of the Kings of France. Almost all of the kings from the 10th through 18th centuries were buried here, along with several earlier kings and one of the two post-Revolution kings.

Origins

There was a small Gallo-Roman settlement here in the 2nd century CE. It was called Catolacus (or sometimes Catulliacum), probably because there was a prominent land-owner named Catullius.

Denis, or Denys, the first bishop of Paris, was martyred around 250 on Montmartre hill near the city. He was buried here in the settlement's cemetery. His grave became a shrine. People started to make pilgrimages, and they needed food, places to stay, and souvenirs. The town began to prosper.

The legends say that Denis was the bishop of the Parisii, a Celtic people living on the banks of the Seine river during the Iron Age. Denis and his companions Rusticus and Eleutherius were martyred on the tallest hill near the settlement that became Paris. The hilltop may have been a holy place for an older religion threatened by the increasingly popular Christian faith.

The hill was then well outside the Parisii settlement. Today it is known as Montmartre. The current name may be derived from the Latin Mons Martyrum, or "The Martyr's Hill". But it's at least as likely that it's derived from Mons Mercurii et Mons Martis, "Hill of Mercury and Mars".

Martyrologies compete for gruesomeness. Denis, Rusticus, and Eleutherius were said to have been imprisoned for some time, and then beheaded by sword. Then, the legend claims, Denis picked up his head and walked several miles north, preaching a sermon the entire way. He is usually depicted as a cephalophore, posed naturally except carrying his head in his hands. Yes, there are enough beheading martyrologies that there's a word for their depiction.

Around 475, Geneviève, who became the patron saint of Paris, purchased land and built an abbey with an associated church. The abbey and its church were named after Denis. She built a small chapel on his tomb.

Today's structure grew out of the abbey church.

These day's it's called a basilica, although the

strict terminology is:

Cathedral means the seat of a bishop,

which Saint-Denis became in 1966.

Basilica means, to

architects and historians, a specific cross-shaped design.

To the Roman Catholic church, since the 18th century,

bascilica means that it has certain ritual

privileges and obligations.

Saint-Denis isn't officially a basilica.

King Dagobert I rebuilt the chapel as part of a monastery under royal favor. He granted many privileges to it, both religious and financial. Dagobert made the abbey of Saint-Denis independent from the Bishop of Paris, and he also granted it the right to hold a market.

In 636, Dagobert ordered that the relics of Saint Denis be moved to the abbey church. He started the pattern of being buried there, and most of the following kings of France were also buried here.

The town became more prominent. By 832 the king had granted the abbey a whaling concession off the Cotentin peninsular. That's at the far end of Normandy, near Brittany, so the abbey was connected into significant trading networks. In the middle ages, merchants from as far as the Byzantine Empire visited the abbey's market.

Louis IX died at Tunis during the Second Crusade, during an epidemic of dysentery that ravaged his army. His younger brother, Charles I of Naples, transported his heart and intestines for burial in a cathedral near Palermo. The rest of his body was boiled until only the bones remained, and they were transported here for burial.

Denis came to be considered as the patron saint of the French people, while Louis IX (1214-1270, proclaimed a saint in 1297) was the patron saint of French royalty. But the kings and queens were buried at Denis' church.

Let's visit!

Start by getting on the Métro. We need to go north on the Métro Line 12 to its next-to-last stop, almost 10 kilometers north of the center of Paris.

I visited on a Monday, when a busy market was underway. I saw no whale products, but they seemed to have everything else.

Wars

The city suffered during the Hundred Years' War, which was actually the 126 Years' War as it lasted from 1337 to 1453. The city had about 10,000 citizens at the start of that war. By its end, only about 3,000 remained.

Then the French Wars of Religion came along a century later, in 1562-1598. That was 36 years of Christians slaughtering each other for being the wrong type of Christian. The Battle of Saint-Denis was a prominent fight between Catholics and Protestants on 10 November 1567. The war ground on. The city surrendered to Henry III, King of Navarre, in 1590.

Henry had been a Hugenot, leading a Protestant army against the royal army of France. He became allied with the French king, who was confusingly named Henry III of France. They wanted to take back France from the control of the Catholic League.

When Henry III of France was assassinated, Henry of Navarre became the nominal king of France. However, the Catholic League was backed by Spain, the Catholic nobles abandoned him, and the Pope excommunicated Henry and declared him ineligible for the throne.

Henry's mistress and confidant Gabrielle d'Estrées convinced him to convert. He would be resented by the Hugenots and his former ally Queen Elizabeth of England, but he would be king.

Henry said "Paris vaut bien une messe", or "Paris is well worth a mass", and converted to Roman Catholicism in this abbey church. Now he became Henry IV of France, the first of the Bourbon line. He soon issued the Edict of Nantes, granting toleration to the Hugenots.

Below, we're arriving at the west end, the entrance to the church. Today it has one tower. It used to have two. The one on the left or north side had an identical rectangular tower section, topped with a much taller tapering spire. Originally, it was 86 meters high.

Cracks appeared in the north tower's masonry after several extreme weather events in the 1840s. A violent storm in August 1845 had spawned a tornado. It flexed the north tower's walls and left it dangerously unstable. In February 1846 the local authorities decided to temporarily dismantle the north tower to prevent a catastrophic collapse. They marked and stored the stones for later reconstruction, which still hasn't started.

170 years later, in December 2016, the Ministry of Culture again proposed rebuilding the north tower. But, the government would provide no financial support. The Suivez la flèche (or "Follow the Spire") association is working to raise the needed funds by opening the reconstruction works to the public. The Ministry of Culture signed an accord with the association in March 2018, hoping to start the work in May 2020.

Enough history. Let's go in.

The church is 108 meters long and 39 meters wide. It is built in the basilica form, with a long central nave with lower parallel aisles down both sides, and cross arms.

The pipe organ, seen above, was added in 1841. Its design was very innovative for its time.

Abbot Suger's Invention of the Gothic

Suger's family gave him to the abbey of Saint-Denis as an oblate at the age of 10. He studied at two church schools, and eventually became secretary to the abbot of Saint-Denis. He was made provost of two communities in Normandy, and then sent to the court of Pope Gelasius II and his successor Calixtus II.

Suger became abbot of Saint-Denis in 1122. As a friend and confidant of two successive kings of France, Louis VI (known as Louis the Fat) and Louis VII, he decided around 1135 to enlarge the abbey and rebuild its church. Suger didn't design the new church, but he supported some unknown architect with a radical new design.

The existing building was of the Romanesque or even pre-Romanesque design. Rectangular, plain, with thick walls and a simple roof. The most elaborate part of that type of design was typically an arched ceiling, a half-cylinder like half of a large pipe.

The first church mentioned in the chronicles had been started in 754 under Pepin the Short. It was completed under Charlemagne, who was present when it was consecrated in 775. Excavations in the 1930s showed that the 8th century structure was about 60 meters long, of the basilica layout, and with its long eastern apse built over a large crypt. Parts of that crypt remain today, beneath the altar.

A large marker in the choir indicates the approximate location of Dagobert's tomb, down below in the crypt.

Sugar's architect started at the west end, at the entrance. He demolished the façade with its single doorway. He built its replacement much further back from the altar, adding four bays to the nave and a large western narthex or entry area just within the doors.

This Pseudo-Dionysius or Pseudo-Denys was sometimes confused, or at least willingly conflated, with the Denis of Paris. Although he wrote in the late 5th to early 6th century, he portrayed himself as Dionysius the Areopagite who met the apostle Paul and was accepted as such in western Europe until the 15th century.

Once that was done, they moved to the eastern end. Suger was fascinated with light. Like many French clerics at the time, he was a follower of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a mystic who equated the slightest reflection or glint with divine light. By the end of the project, Suger's words had been carved into the nave:

and bright is the noble edifice which is pervaded by the new light.

The choir or chancel was to be replaced with an entirely new design that was flooded with light. The architects incorporated several new elements that had recently been added to the rather plain Romanesque architecture. The ambulatory is a passage around and behind the high altar, with radiating chapels. The semicircular end is called the chevet, a French word for the head of a bed — with the church in the shape of a cross, the chevet is where Jesus's head would be. The roof and windows would use the pointed arch, the rib vault, and clustered columns supporting ribs radiating in several directions. Finally, flying buttresses allowed the upper walls to be mostly glass, clerestory windows.

The column next to the lectern holds a statue of Denis in cephalophore form, carrying his head.

All that was finished and dedicated in June 1144, with King Louis VII in attendance.

Suger died in 1151. The church had been enlarged and converted into a radically new design, at least at both ends. The old Romanesque nave still connected the two ends. The new style became the prototype for new churches in France, and spread to the Low Countries and Germany, to Spain, to Italy, and across the Channel to England. It was called Opus Francigenum or "Frankish Work". The term "Gothic" appeared some five centuries later, trying to blame this supposedly barbarous style on the Goths.

Abbot Odo Clement began the reconstruction of the old nave in 1231. His men replaced and enlarged the old nave and crossing. They also replaced the upper parts of Suger's choir or chancel area.

The church began transforming into the French royal necropolis. The bones of 16 former kings and queens were transferred here in 1264 at the order of Louis IX. He was designated Saint Louis soon after his death, for his religious zeal. He spent exorbitant sums on relics, expanded the scope of the Inquisition, ordered the burning of Talmuds and other Jewish books, and took part in the Seventh and Eight Crusades. He died of dysentery during the last of those.

Louis IX wanted to demonstrate that the Capetian dynasty, of which he was a part, was heir to the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties. Recumbent effigies or gisants were created for them.

Eight Carolingian monarchs were installed at the south arm of the crossing. In the first picture below, the near one is Clovis II (633-657). He was King of Neustria and of Bourgogne from 639 to 657. He was a minor for most of his reign. Medieval monks thought he had been insane, an example of a roi fainéant or "do-nothing king", the rather hapless later Merovingian kings.

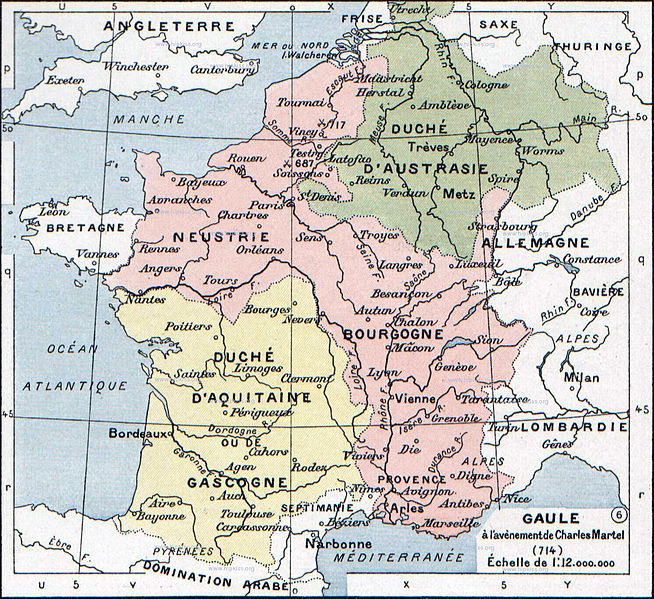

The far one is Charles Martel (688-741). He turned out much better. He was Duke and Prince of the Franks, and Mayor of the Royal Palace (or Majordomo) of Austrasia and Neustria 718-741, and de facto King of the Franks 721-741.

Frankish lands in 714, from Paul Vidal de la Blanche's Atlas général d'histoire et de géographie, 1912

Even older kings were moved here in the late 1810s. Below are two who were originally buried at the churches of Sainte-Geneviève and Saint-Germain-des-Prés and Paris, with statues carved in the 12th and 13th centuries. These are along the side of the presbytery, the chancel or sanctuary around the high altar.

The far one is Clovis I (466-511). He ruled as King of the Franks 481-511. He was the first to unite all Frankish tribes under one ruler.

The near one is Clovis' son, Childebert I (496-558). He ruled as King of Paris 511-558, and of King of Orléans 524-558. He and his three brothers shared the kingdom of the Franks after their father's death.

The French Revolution

The French Revolution occurred in 1789-1799. For obvious reasons the monarchy and church were both seen as totally corrupt. The Revolutionaries wanted to eliminate both. They closed most churches and converted some into "Museums of Atheism", a move copied in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution of 1917. The city was named for a Roman Catholic saint, so it was renamed Franciade.

The abbey of Saint-Denis was closely connected to the monarchy, and it was close to Paris. So, it was a prime target of Revolutionary destruction.

The Revolutionaries demolished the medieval monastic buildings in 1792. They left the abbey church building standing, but they confiscated the treasury and liturgical furniture and equipment, melting it down for the metallic value. They desecrated the royal tombs, and removed the carvings of Old Testament figures they had mistaken for early French royalty.

Then they looted the royal necropolis. They removed the remains from the tombs and dumped them into mass graves, covered with lime to destroy them. The ancient monarchs were removed in August 1793 to celebrate the Revolutionary Festival of Reunion. Then the Bourbon and Valois monarchs were removed to celebrate the execution of Marie Antoinette in October 1793.

The recumbant statues of the buried royalty were saved by being reclassified as artwork. The archaeologist Alexandre Lenoir claimed many of them for his Museum of French Monuments.

Small statues of Old Testament figures on the façade were misunderstood as French kings, and destroyed. So much for the theory that stained glass windows and statuary are clearly understandable visual lessons for the illiterate masses.

The Revolution had some nutty ideas. There was the Decimal Calendar, with Year 1 beginning the day the monarchy was abolished. It had twelve 30-day months, each divided into three 10-day weeks or décades. Five or six extra days to synchronize with the solar year were added at the end of each year.

| Decimal | Conventional |

| hour | 144 minutes |

| minute | 86.4 seconds |

| second | 0.864 seconds |

Then the days were divided into Decimal Time, with ten decimal hours per day, each hour divided into 100 decimal minutes, and each of those divided into 100 decimal seconds.

$ cal 9 1752 September 1752 Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

It had been bad enough that the Gregorian calendar

had shifted the date by 10 days.

France adopted the new calendar when the Pope announced

it in 1582.

Protestant states in Germany, Switzerland,

and the Low Countries only adopted it in 1700,

and Great Britain in 1752, when the offset had increased

to 12 days.

Border crossings meant calendar changes.

The UNIX-family

cal

command was developed in the U.S., so it uses Great Britain's

change of September 1752, skipping the 3rd through 13rd of

that month.

These unusual base-10 systems of tracking time didn't last for long.

Napoléon

Napoléon Bonaparte seized power in a coup d'état in 1799. He later crowned himself Emperor in 1804. He expanded the French Empire through several military victories, despite some fiascos like marching into Russia in the winter. But then he was defeated by a coalition of European powers in 1814.

Those European powers returned limited power to the Bourbon family, now ruling France as a constitutional monarchy. Napoléon was exiled to Elba, an island just 10 kilometers off the coast of Tuscany in Italy, far too close.

The Hundred Days began when Napoléon returned to Paris on 20 March 1815 at the head of an army. Multiple European armies were ready to face Napoléon's forces. The Great Powers of Europe (Austria, Great Britain, Prussia, and Russia) declared him an outlaw.

Napoleon was soundly defeated at Waterloo, and abdicated three days later, on 22 June 1815. King Louis XVIII was restored to the throne for a second time on 8 July. Napoléon was exiled to Saint Helena, a small island in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean. He died there in 1821, possibly from arsenic poisoning caused by living in a damp house with bright green wallpaper colored with copper arsenite.

Sorting Out the Mess

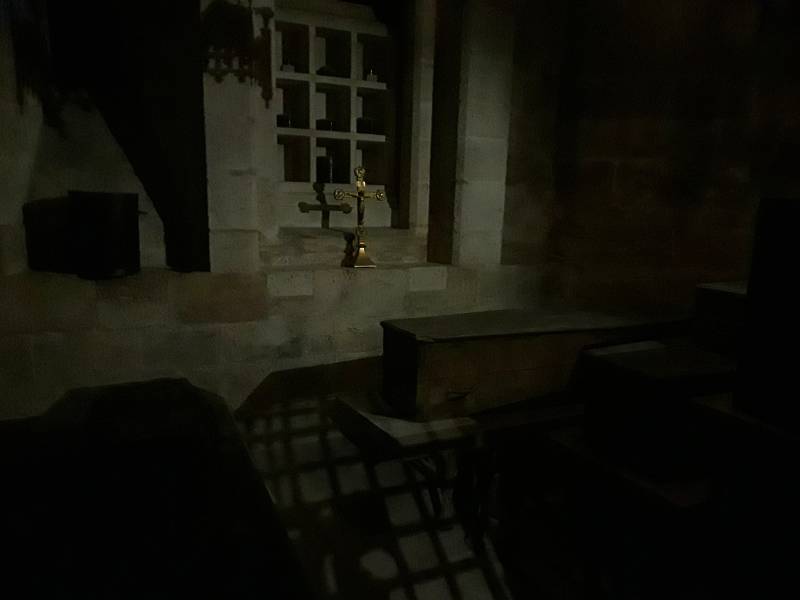

Now that the Bourbons seemed to be permanently restored to the limited power of a constitutional monarchy, they tried to restore the necropolis of Saint-Denis. The royal remains were all mixed together. Mélange royale. So, in 1817 they placed the remains in a common ossuary, and replaced the recumbant statues. The Bourbons fell from power in the July Revolution of 1830. Below is the ossuary, in a small chamber off the crypt.

Wooden caskets in this chapel hold various figures buried here after the Revolution — Adelaide and Victoire, sons of Louis XV; Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, and two children; Louis Henri de Bourbon, Prince of Condè; and Louis Henri Joseph de Bourbon, Duke of Bourbon.

Urns in the 3×3 grid of shelves hold bits and pieces of royal figures originally buried somewhere else.

-

Parts of the bodies of:

- Henry IV (1553-1610)

- Louis XIV (1643-1715)

-

The hearts of:

- Louis XIII (1601-1643)

- Louis XIV (1643-1715)

- Charles Ferdinand d'Artois, Duke of Berry (1778-1820)

- Louis XVIII (1755-1824)

- The entrails of Louise Isabelle d'Artois, infant daught of the Duke of Berry

A side chapel off the crypt is dedicated to the Bourbons, the later royal family.

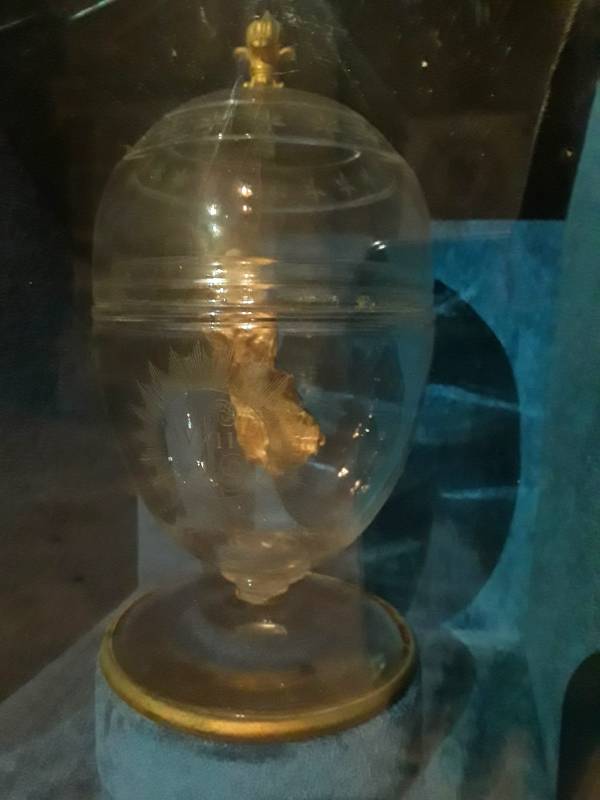

The Dauphin, the son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, had died of illness and neglect while held captive by the Revolutionaries. His heart was removed and preserved. The rest of his body was buried in a mass unmarked grave in a churchyard near Square du Temple in Paris. His heart, seen above, was moved here in 2004. He's the most recent, and presumably the last, addition to the French royal necropolis.

These graves are the newest, they were placed here in the early 1800s. The far two hold Louise de Lorraine (1553-1601) at left and Louis VII (1120-1180) at right. They had been buried elsewhere and moved here in 1815.

The middle two are Marie Antoinette (1755-1793) at left and Louis XVI (1754-1793) at right. Executed by guillotine during the Revolution, they were initially buried at the Cemetery of Madeleine. Their bodies were covered with quicklime.

Louis XVIII was King of France from 1814 until 1824, with a break from March to July 1815 when Napoléon briefly returned. Louis XVIII ordered that Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette be exhumed and moved here in 1815. By that time all they could find were a few bones that were presumably the king's, and a clump of greyish matter containing a lady's garter.

Louis XVIII (1755-1824) is in the near right one.

The one at near left is empty. It was prepared for Charles X, who was the last Bourbon King of France, ruling from 1824 to 1830. He's buried where he died in exile, at the Franciscan Kostanjevica Monastery at Görz (or Gorizia) in the Kingdom of Illyria, today's Nova Gorica, Slovenia.

Napoléon had the church reconsecrated in 1806. For that, he gets his own window in the south crossing, above the side aisle.

By 1830, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were adequately rehabilitated to get their own statues. Unlike Denis, with their heads still attached.

The doorway in the west arm of the crossing depicts the execution of Denis and his two companions.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Cathedral of Notre-Dame at the center of Paris claimed that they had his head. Well, at least the top of it. They said that the executioner's first blow had sliced off the top, which the Paris cathedral got. Then the second blow cut off the rest, which went to the abbey.

Below is a closer look at the abbey's depiction. In their version, Denis brought his whole head to this site.

Saint-Denis Industry and Modern Times

King Louis XIV (1638-1715) had established textile industries in Saint-Denis — dye houses, and weaving and spinning mills.

The Canal Saint-Denis was built in 1824. It connects the Canal de l'Ourcq in the northeast to the River Seine. The city of Paris now contains 130 kilometers of navigable waterways, with the Seine river and three major canals.

All the industry in Saint-Denis required many workers, and thus there was a significant socialist movement. It was called la ville rouge in the 1920s, when all the mayors were members of the Communist Party.

Well-organized labor meant that the city's industry wasn't all that useful to the occupying Germans during World War II. Sabotage and slow-downs were frequent.

The city remained predominantly industrial until recently. The economic problems of the 1970s and 1980s hurt the city. The crime rate remains at almost twice the national average, and the local police are notoriously inefficient, solving just under 20% of crimes.

35.6% of the population of Saint-Denis was born outside Metropolitan France. 18.1% of those are from the Maghreb, the part of North Africa that used to be French colonies.

That means that there are some good places to get couscous!

Where next?