By Ferry Between Napoli and Palermo

Overnight Ferries Between Napoli and Palermo

During a multi-week trip to Italy,

I traveled by overnight ferry between Napoli and Palermo.

Ticket prices vary widely,

like airline tickets and sleeper train tickets.

The price depends on

how far in advance you buy the ticket,

the day of the week and the time of the year for your voyage,

and the demand for tickets so far.

Plan your trip early.

I bought my tickets during the last week of March,

for travel south during the first week of May

and back north during the first week of June.

The first ticket, for a private cabin with no porthole, cost

€ 103.27,

and the second, for a private cabin with a porthole, cost just

€ 89.27.

The second included a cabin with a view and was a month later

into the summer season, and so I would have expected

the costs to be the other way around.

However, the second trip had a much smaller load of vehicles

and fewer passengers,

possibly because it ran the Sunday–Monday night

leading into the national Republic Day holiday.

Plan ahead.

Those struck me as good deals for transportation across

170 nautical miles of the Tyrrhenian Sea

plus a night's lodging.

South from Napoli to Palermo

Mycenaean sailors established a settlement around today's Napoli in the second millennium BCE.

Then, after civilizations recovered from the late Bronze Age collapse around 1200–1150 BCE, the population of Greece began to outgrow the country's agricultural output. The more prosperous and crowded Greek city-states began to establish colonies around the Mediterranean. One was established on the shore of today's Napoli harbor in the 8th century BCE. It was refounded in the sixth century BCE a short distance inland, around today's Centro Storico, named Νεάπολις or Neápolis, "New City", Rome seized control of the city and its harbor in 325 BCE, but Neápolis retained its Greek culture for centuries.

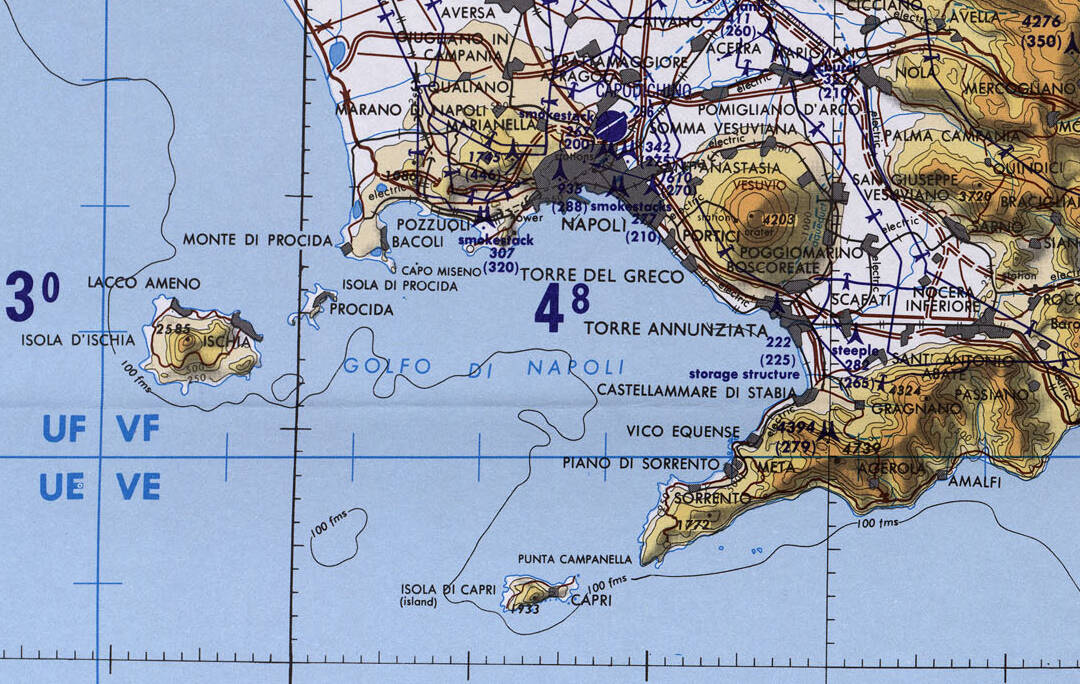

Part of aeronautical chart TPC F-2C showing Napoli, its harbor, and Mount Vesuvius, from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. The ferry would depart to the south-southwest, passing outside of Capri.

Tickets

Grandi Navi Veloci or GNV operates ferries between mainland Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, France, Spain, Albania, Morocco and Tunisia.

The passenger ferry area of Napoli's port is large. I had found the GNV offices and boarding area soon after arriving in Napoli, before continuing south to Salerno and Paestum. When I returned by train from Salerno to Napoli, I knew exactly where to go.

My southbound trip to Palermo would be on the MS GNV Antares, built in 1985–1986 in Yokohama. It entered service for North Seas Ferries in 1987, operating between the west coast of Britain and both Belgium and the Netherlands. It was taken out of service in the North Sea in late 2020 due to COVID-19, and sold to GNV. It's a large ferry — 31,598 gross tonnes, 179×25 meters, carrying up to 888 passengers and 850 vehicles.

The southbound trip was scheduled to leave Napoli at 20:00 and arrive in Palermo twelve hours later, at 08:00. They told me that check-in was from 18:00 to 19:15, but they also mentioned that check-in was possible from 17:00 onward.

Check in early. The early passengers can get on board before the crew begins loading long strings of vehicles. If you were to show up around the middle of the announced boarding period, you might have to stand in a line and wait quite a while before they pause vehicle loading briefly.

The ship's old affiliation is still visible.

The GNV Antares has a single broad ramp, making for longer passenger waits while vehicles are loaded.

Once on board I was directed up a few decks to the on-board check-in desk to get the key to my cabin.

I had my own head with toilet and shower, very nice!

Deck 7 was crew only with the bridge above that. Deck 6 had a large lounge and bar, which was quiet soon after I boarded. It had a karaoke stage for when we got underway and the alcohol took effect.

Aft of the lounge, between it and the open aft deck, was a block of cabins. I traversed its corridors through a large group of 5th-8th grade kids, many standing in groups furiously texting and blocking the passageway while the rest sprinted and shouted.

A boy had found an unlocked crew-only storage locker and pulled out a large aerosol can of disinfectant. He was emptying it as fast as possible, filling the passageway with a thick pungent fog and causing the others to scream louder.

Decks 5 and 4 were calmer, cabins and lounges and restaurants and spaces with rows of seats. My cabin was on 5. Decks 3 and 2 held cars and small trucks, deck 1 was for large trucks.

The open area on deck 6 provided a view across the harbor to Vesuvius.

The current generation's Sergio Leone was moving some cargo.

Vesuvius is a dangerously active volcano given its short distance from Napoli. But no, it wasn't venting ash that day. A lenticular cloud forms when wind pushes an air mass over a mountain and the resulting drop in pressure and temperature brings water out of suspension above the peak.

I would see actual ash, steam, and gas venting from volcanos in the coming days — Vulcano, Stromboli, and Etna.

We pulled away from the pier almost 20 minutes after the announced departure time, but the departure and arrival times on these ferry runs are approximate. We were tied up in Palermo and I was out on the pier by the announced arrival time there.

The sun had set by the time we were moving out through the inner harbor.

We had a seagull escort.

Forty minutes later we were nearing Sorrento and the Sorrentino peninsula.

The island of Capri lies off the end of the peninsula. We would pass outside Capri and then head almost due south to Palermo.

An hour after pulling away from the pier, moving at the ferry's top speed of 19 knots, Vesuvius was still visible against the glow of Napoli.

Departure and arrival times are somewhat approximate. Announcements begin well before actual arrival in the morning, letting everyone know when various lounges and cafes re-open.

North from Palermo to Napoli

After three and a half weeks traveling around Sicily, it was time to make my way back to Rome to fly home. I would take the reverse ferry passage, from Palermo to Napoli.

Part of aeronautical chart TPC G-2B showing Palermo, from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

The north-bound schedule was similar: depart Palermo at 21:00 and arrive at Napoli at 10:00. I made sure to get to the pier by 18:00, the start of the announced boarding period.

I would be on the MS GNV Blu, which had similar characteristics. 31,910 gross tonnes, 164×28 meters, carrying up to 1,320 passengers and 455 vehicles. Very similar size, 50% more passengers, about half the number of vehicles.

I showed my ticket and identification at the gate under the tent.

The ferry was built in 1986, originally named MS Koningin Beatrix and operating between the Netherlands and the UK. She was sold to a Swedish shipping line, renamed Stena Baltica and put on the Karlskrona-Gdynia route across the Baltic Sea. Then, in 2015, sold to GNV for service across the Adriatic between Bari, Italy, and Durrës, Albania.

With two ramps they could load vehicles through one and passengers through the other.

You show your ticket and ID again just past the top of the ramp.

Then it's a long walk forward to the ladders and elevators leading up into the ship.

I went up to the deck with the check-in desk and got the key to my cabin. My cabin on the southbound trip had four bunks, this one had just one. Otherwise, a very similar setup.

A friend of mine saw my pictures and commented that it looked very comfortable, which it was. He went on to say that he could see himself going on a much longer voyage in such a cabin, getting some writing done.

And so I had to tell him, and also you, dear reader, about Evelyn Waugh's wonderfully cautionary tale of Gilbert Pinfold. It's a surprisingly autobiographical novel based on Waugh's mental breakdown on a sea voyage from England to Ceylon. He was under some self-imposed mental stress, and was self-medicating with a combination of chloral hydrate, bromide, and crème de menthe. The first two are sedatives and hypnotics that had been popular in the late 19th century and were still available over the counter. The last is a mint-flavored liqueur.

His auditory hallucinations began almost as soon as his ship pulled out. He heard sounds coming from the overhead of his cabin. Radio static at first, joined sequentially by barking dogs, frantic jazz music, and evangelical tent revivals.

His exploration of the deck above his and his pointed questioning of fellow passengers and the crew provided no explanation, although they contributed to his reputation on board. Then voices joined the clamor. They initially were talking about him, but then shifted to talking to him, criticizing him and taunting him.

Waugh wrote a stream of letters to his wife, describing all this. He gave the letters to the crew to be posted at the frequent port calls. Mrs Waugh, of course, became alarmed by these developments.

Waugh left the ship at Alexandria, Egypt, and flew to Colombo. However, the sinister taunting voices continued. Once in Colombo, he checked into a hotel and continued sending frightening letters to his wife. She convinced a friend to accompany her to Ceylon to bring him home. But before they could leave, with no warning he suddenly appeared at home, having bought an air ticket back to London.

A friend who was a Jesuit priest, and thus quite authoritative to the Roman Catholic Waugh, finally convinced him to see a psychiatrist. Waugh confessed his self-medication regimen, and the psychiatrist immediately saw the problem (as anyone today should). He convinced Waugh to replace the chloral hydrate and bromide with paraldehyde, a slightly less hazardous central nervous system depressant, hypnotic, and sedative. The auditory hallucinations stopped almost immediately.

The information panel beside the door showed that the ship had been in service on a route between Italy and Albania. So many xh and sh and mb and ë.

I stored my things in my cabin and went out on deck to watch the rest of the loading.

Other ferries were preparing to leave.

Palermo's harbor is famous for its dramatic appearance with mountains on either side. The 600-meter Mount Pellegrino is immediately north of the harbor. The German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe praised the harbor in his book Italian Journey, describing his travels 1786–1788.

The sun set as our preparation continued.

They raised the ramps and we pulled out about twenty minutes after the official departure time.

I got an Aperol spritz at the bar on the aft deck and set at the rail watching our departure. No chloral hydrate, no crème de menthe, just Aperol, Prosecco, and soda.

I had a quiet voyage north to Napoli. No frantic jazz bands. No mobs of kids unleashing fogs of disinfectants.

By morning we were close to Napoli, passing Capri and Sorrento and approaching Vesuvius.

Before 08:10 a pilot boat was coming alongside.

The pilot steps on board through a hatch close to the ferry's waterline, then heads up to the bridge to bring the ship into the harbor.

We were scheduled to arrive at 10:00, but I was off the ship and on the pier by 09:30.

Where Next In Italy?

( 🚧 = under construction )

In the late 1990s into the early 2000s I worked on a project to

scan cuneiform tablets

to archive and share 3-D data sets,

providing enhanced visualization to assist reading them.

Localized histogram equalization

to emphasize small-scale 3-D shapes in range maps, and so on.

I worked on the project with Gordon Young,

who was Purdue University's only professor

of archaeology.

Gordon was really smart,

he could read both Sumerian and Akkadian,

and at least some of other ancient languages

written in the cuneiform script.

He told me to go to Italy,

"The further south, the better."

Gordon was right.

Yes, you will very likely arrive in Rome,

but Italy has domestic flights and a fantastic train system

that runs overnight sleepers all the way to

Palermo and Siracusa, near the western and southern corners

of Sicily.

So, these pages are grouped into a south-first order,

as they should be.