Pompeii and Vesuvius

The Sudden End and Preservation of a City

Pompeii

was a wealthy Roman city of 10,000 to 20,000 residents when,

in 79 CE, the nearby volcano Vesuvius

underwent an explosive eruption that buried the city

under four to twenty meters of volcanic ash and pumice.

The eruption began suddenly and was over in just two days,

preserving life in Pompeii at the time.

Private homes, small businesses,

and public buildings were all well preserved.

Food and drink preserved in shops and taverns

tell us about the diet, daily life, and business practices.

A collection of tablets in the home of a banker

revealed economic practices of the period.

I had visited in 2009, and some of these pictures and

observations are from then.

The majority are from my return in 2025.

There were changes —

some things that in 2009 were not open

or were still completely buried

could be seen in 2025.

However, some places that I saw in 2009

were not open at my later visit.

Some closures were due to changes in what was being

investigated or conserved,

others were to protect more delicate paintings and frescos.

Pompeii has been a popular tourist attraction

since the 17th century.

By the time I returned in 2025,

the numbers had climbed to

around 3.5 million visitors per year,

and a limit had been placed on

the number of visitors per day.

Buy your ticket online

before taking the train from Napoli.

You will know that you can enter that day,

and you will avoid some very slow lines.

Portion of aviation chart TPC F-2C, from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. The ancient site is between the built-up areas marked as Torre Annunziata and Scafati on this chart.

Origins of Pompeii

The Mycenaeans established a settlement in the second millennium BCE near today's Napoli, called Naples in English. In the sixth century BCE, it was re-founded as Νεάπολις or Neápolis, the "New City", and it became one of the leading cities of Μεγάλη Έλλάς or Megáli Éllás, the Greek-speaking settlements of southern Italy.

The Osci or the Oscans lived in the area well before Roman times. Much of our supposed history of them is legendary, but they are known to have established settlements on the site of Pompeii in the 8th century BCE. The Greeks arrived here around 740 BCE.

The Osci spoke an Indo-European language shared by other nearby tribes, and the Oscan language co-existed with Greek for several centuries. The Osci were assimilating into Roman culture, and their Oscan language became extinct soon after the destruction of Pompeii.

Pompeii allied itself with Rome in the Second Punic War of 218–201 BCE and supported Rome's conquest of the east through the second century BCE. Pompeii became a Roman colony after the Social War of 91–88 BCE, the Pompeiians were granted Roman citizenship, and Latin became the city's main language.

The city is close to the southeast base of the volcano. Here are visitors in the Forum with Vesuvius in the background.

The Eruption and the Plinys

Residents of the area were accustomed to minor earthquakes. However, a strong earthquake on 5 February 62 CE caused serious damage to Pompeii and other settlements around the bay. Much rebuilding was done during 62–79 CE. Some buildings newly constructed during that narrow window of time included the very latest developments in wall heating and window glass.

The catastrophic eruption that buried Pompeii happened over a two-day span in 79 CE. It was preceded by four days of minor earthquakes, nothing unusual in the area.

Pliny the Elder is largely known today as a naturalist and author of a 37-volume work covering a wide array of topics on human knowledge and the natural world. He had also become a naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire.

He helped to raise and educate his nephew Pliny the Younger, who became a lawyer and author. Pliny the Younger's account of the eruption, written years later, is our only eye-witness source. He observed it from Misenum, 29 kilometers away, across the bay. Stratigraphic studies, analyzing the deposited layers, have provided much further information.

Vesuvius began violently erupting about a hour after noon, sending up a column of volcanic debris and hot gases reaching 15 to 30 kilometers into the stratosphere. That phase of the eruption lasted for 18 to 20 hours. The first few hours within that phase deposited white pumice in fragments up to 3 cm in diameter, and heated roof tiles to 120–140 °C.

That would have been the last chance for residents to flee Pompeii, and it seems that many to most of them did, carrying portable valuables with them. Homes were richly decorated with frescos and mosaics, but contained very little in the way of dishes, portable decorations, jewelry, etc. However, over 1,000 out of the 10,000 to 20,000 residents remained in the city and were soon killed.

A second column of hot gases and ash then deposited grey pumice for the remainder of that initial 18–20 hour phase, with pieces up to 10 cm in diameter and higher temperatures. The layer of pumice and ashes averaged 2.8 meters deep over Pompeii and the surrounding area at the end of the first 18–20 hour phase.

Then there was a strong earthquake which, coupled with the heavy load of pumice and ash on the roofs, caused several buildings to collapse.

Next there were multiple pyroclastic surges, those being dense, high-speed flows of hot gases carrying ashes and molten rock. The pyroclastic surges reached as far west across the bay as Misenum, causing Pliny the Younger and his mother to flee toward the north.

Meanwhile his uncle, Pliny the Elder, taking charge as naval commander, had launched a rescue mission across the bay to try to save a personal friend living in Pompeii (and, of course, observe this fascinating though dangerous phenomenon at close range). He did not survive. But a famous naturalist sailing into a cataclysmic volcanic eruption, that's a movie-hero death. Pliny the Younger failed to write the screenplay.

The pyroclastic surges were concentrated toward the south, first engulfing Pompeii with a 1.8-meter layer of different makeup. These surges would have asphyxiated and burned any people who had remained behind, with ash cloud temperatures climbing to 850 °C at the point of eruption, and still at 300–360 °C as it reached the city. Some people had remained behind, staying within less hot areas. Their bodies famously were burned away within that later hot ash layer, leaving voids which were filled with plaster by earlier investigators, by clear resin more recently.

Later pyroclastic surges deposited up to 20 meters of finely pulverized pumice and lava fragments burying Pompeii along with Herculaneum, Oplontis, and other nearby settlements. The ash stopped falling late on the second day, with the sun visible only weakly through the remaining airborne ash.

Twenty-five years later, Pliny the Younger, who had been seventeen years old when Vesuvius erupted, wrote two letters to the historian Tacitus. The first described what he was able to learn from witnesses who had shared or seen his uncle's experiences. The second describes his own observations in detail, using his uncle's teachings of how to observe, record, and describe natural phenomena.

His clear descriptions of his observations has led to Plinian becoming a standard term for this type of eruption, in which columns of hot gases, ash, pumice, and other volcanic debris are launched high into the stratosphere with powerful and continuous gas flows.

What Were They Thinking?

Why did they build Pompeii in such a dangerous place? The location was good for business. It had a good harbor and was connected to a major north-south road. It was surrounded by fertile farmland, not the rugged mountains otherwise dominating the region. And, the 79 CE eruption didn't scare people away from Vesuvius permanently.

Vesuvius was active from 1913 through 1944, with a major eruption in March 1944. The Allied invasion of mainland Italy had begun in September 1943 with Operation Avalanche, landings on a 55-kilometer stretch of beaches between Paestum and Salerno, a short distance to the south. Nine months later, during that major eruption, the U.S. Army Air Force's 340th Bombardment Group was based at an airfield just a few kilometers east of the base of Vesuvius. Between 78 and 88 B-25 Mitchell bomber aircraft were destroyed by hot tephra and ash falling on their fabric-covered control surfaces, engines, and Plexiglass windscreens and gun turrets. Why was the unit based there? It was an existing airfield close to the essential port of Naples where supplies were arriving.

The modern Italian government could tell you that there's just no accounting for people's continuing desire to live close to, or even on the slopes of, an extremely dangerous volcano. By the 1990s into the 2020s, the government was trying to reduce the number of people living dangerously close, by demolishing illegally constructed dwellings, establishing a national park around the volcano to prevent future construction, and offering financial incentives to people who move away.

Initial Discoveries and Early Tourism

Despite the depth of ash cover, the tops of some structures protruded above the surface and provided clues for people wanting to salvage material or hunt for treasure. Those activities ended, and further ash deposits through following centuries finished burying what had been visible after the big eruption of 79 CE. The city was known to history but physically lost.

An architect digging an aqueduct rediscovered the site in 1592, but there was no serious excavation.

Early digging at Pompeii was haphazard, largely treasure hunting with little to no science or history. Western European royalty and extremely wealthy businessmen wanted statues and architectural fragments. Of course they also wanted ornamental objects of precious metals decorated with jewels, but the residents had carried those portable objects away during the initial hours of the eruption.

The Forum and some of the paintings in grand houses were exposed first, having been early diggers' goals. They demonstrated art and architecture then known mostly through historical descriptions and artists' imaginings. Pompeii soon became a popular destination along the "Grand Tour" of Europe through the 17th to early 19th centuries. Wealthy young men, mostly from northern Europe, followed a standard itinerary through sites of classical culture. The Grand Tour had a focus on Italy, what with Greece still being under Ottoman control.

The first excavations with scientific goals began around 1750. Scientific archaeology began to take form at Pompeii. Giuseppe Fiorelli, who took charge of excavations in 1860, realized that voids in the ash layers containing human remains were spaces left by decomposed bodies. He came up with the technique of injecting plaster into these voids to recreate the victims.

PLOS One, June 2010

These fascinated the public, with their lurid appearance of the victims having died while writhing in agony. However, with the pyroclastic flows raising temperatures above 300 °C almost instantly, the victims died within a fraction of second. Their poses were caused by cadervic spasm, the result of heat shock on a corpse.

The casting technique has been improved with the use of clear resin, preserving the visibility of any bones or internal organs that remain.

Recent Developments

— As do you, Doctor Jones.

Other than illicit treasure-hunting operations still undertaken on behalf of oligarchs and industrialists, of course.

Archaeology now strives to understand the individual people and the cultures of the past. Experts in well-equipped laboratories associated with museums and universities study material in the field or back in the lab. What was the day-to-day life really like for these people? What did they wear and eat, and where did they obtain that clothing and food? What were their jobs like? Their entertainment? Their religion?

For example, new forms of wall heating and window glass installed during that brief 62–79 CE window tells us when those were developed.

Pompeii's snapshot of the initial few hours of the eruption has been extremely valuable. We now understand much more about food processing, service, and consumption, along with local industries including wool processing.

For example, by 2025 we had learned that Pompeii had at least 31 bakeries, each with grain mills, wood-fired ovens, and a sales counter. Below is a grain-milling area.

The two cones to the right of the columns are the stationary parts of grain mills, called the meta. The object at the left rear is a complete mill. The object with a hyperboloid outer shape, the catillus, has a cone-shaped opening at top and bottom. It has been placed over the stationary cone of that mill.

You would feed grain into the opening at the top of the catillus and then have slaves or animals rotate it with a wooden pole placed horizontally through the hole passing through its center, perpendicular to its vertical axis. The grain would go down between the rotating inner hyperboloid surface and the stationary cone, be crushed and ground, and come out at the bottom of the rotating part to fall into the circular channel around the base. Keep feeding whole grain into the top and removing ground grain from the bottom. Repeated passages or smoother mill surfaces would produce finer flour.

Pompeii had nearly one hundred thermopolia, taverns or inns selling drinks and food. Most opened directly onto the sidewalk running along one side of a street. Many had a room in the back where customers to could sit and eat their meals, possibly visiting with friends.

An amphora was a ceramic or earthenware vase-like container, narrow and approximately cylindrical. The original designs were introduced by the Greek colonists. They were most often used to transport and store liquids such as wine or olive oil, but were also used for grain, flour, beans, and so on. A standard wine amphora held about 39 liters.

A dolium, on the other hand, was much larger. It had a broad opening and rim, no handles, and was much more oval to spherical in cross-section. Some were flat-bottomed, but the majority had roughly spherical bottoms. They were lined with wax or pitch to handle liquids and solid foods.

There was no standard dolium size, but the largest examples held up to 1,300 liters each. They would typically be built into shops, as you see at Pompeii. Specialized transport ships were built around two or three rows of dolia along and parallel to their keels.

A tavern might buy wine in amphorae from a supplier, then pour multiple amphorae of wine into a dolium built into the counter or mounted along the wall of the serving area of the establishment.

Red wine into this dolium, white wine into that dolium, soup or beans or whatever into the next one.

If you wanted a cup of wine with your meal, it was dipped out of the dolium. If you wanted a large quantity of wine to restock your personal supply, you would bring your own amphora and have it filled, like taking a "growler" jug to a brewpub (at least in U.S. English terminology). Amphorae were portable, dolia were not.

Then there was the wool processing, a significant industry at Pompeii. So far, researchers have found thirteen workshops that handled the raw material, eighteen that washed wool, seven that spun wool into yarn, and nine that dyed the yarn. Other shops produced and sold finished woolen goods.

The cleaning stage is called fulling, or tucking, or walking. This removes oils and dirt, and is followed by milling or thickening.

These pictures show a series of tanks used for fulling wool at Pompeii. The smaller tanks are for treading and fulling, the larger ones are for rinsing.

Ammonium: NH4+

The cleaning or scouring process during Roman times was based on human urine. Urine contains ammonium salts, which are components of modern soaps. Read your shampoo bottle — my handy bottle of shampoo lists ammonium lauryl sulfate, ammonium laureth sulfate, and ammonium chloride.

A wool fulling operation had to purchase the wool itself from shepherds in the surrounding countryside. But the urine needed for processing might be obtained quite cheaply or even for free.

One of the wool fulling businesses along the main street of Via dell'Abbondanza famously had a sign asking male passersby to please contribute via the jars hung on the wall. See "The Production of Woolen Cloth in the Roman World", Walter O. Moeller, 1976, page 20:

Since water was of great importance to the fullers, they had to have their establishments near sources and needed guaranteed water-rights (below, p. 96). And as with water a sure supply of urine was a prime concern. So that it might not go to waste, the fullers set out jars in the street outside their shops as a public convenience, thereby collecting some of their supply free of charge. [162] Yet since animal urine was also used, much of the substance must have been imported from the farms to the cities, and if camel urine was prized, as Pliny (HN XXVIII. 91) reports, then urine must have entered into an extensive trade pattern. Other arrangements, however, had to be made to collect the vast supply of human urine generated in the cities (below, p. 96).

Later technology included fulling mills with arrays of water-driven broad wooden mallets to repeatedly stamp the wool immersed in its ammonium-laden bath, a mixture that combined urine with fuller's earth, a clay-like material with high magnesium oxide content. But back in Roman times, this was done by slaves stomping away in urine from ankle to knee deep.

"Urine? Ick! How ancient and primitive!", you say. However, urine for a surprise, as they say, because...

Shakespeare and the Birth of the English Chemical IndustryWhen King Henry VIII of England wanted a divorce and the Pope wouldn't give him one, Henry split the Church of England off the Roman Catholic Church. One immediate problem was that the Pope controlled the European alum industry, and alum was needed by the textile industry as a mordant, a chemical to make dyes "bite into" textiles. So in the 16th century CE, England began collecting and shipping up to 200 tonnes of human urine every year to support domestic production of alum needed to dye English textiles. This was a big deal and part of everyday commerce, to the point that it was mentioned in Shakespeare's plays.

I'm with the modern archaeologists who find all of this far more interesting than "Oh, look, another fancy fresco of some fauns and nymphs."

Putting Things Together

Interdisciplinary studies can really advance overall knowledge. Until recently, the eruption was believed to have happened in August, but discoveries published beginning in 2010 show that it probably happened in October or November of 79, most likely in late October, because:

- The initially known description by Pliny the Younger says it happened on 24–25 August, but that was probably a transcription error, and a recently discovered version said that it happened in November.

- The people buried in the ash were wearing heavier clothing than would be typical for August.

- The fresh fruit and vegetables found in the shops were those of October rather than August.

- Summer fruit typical for August were being sold in dried form.

- Chestnuts, which would not have matured before mid-September, were found in shops in nearby Oplontis, similarly buried in the same eruption.

- Wine fermenting containers had been sealed, which would have been done around the end of October.

- A woman's purse had coins minted after the second week of September of 79, based on the events they commemorate.

See the collaborative paper in Earth-Science Reviews and the overview in ANSA English.

Baths at Pompeii

This was a Roman city, so of course there were baths, containing the standard three chambers: frigidarium, or cold room; tepidarium, or warm room; and caldarium, or hot room. The two most prominent ones were Terme del Foro and Terme Stabiane — Italian names, so "Forum Baths" and "Stabiane Baths". These are the Stabiane Baths:

Hot air from furnaces was run in beneath the elevated floors of the caldarium, a system called a hypocaust.

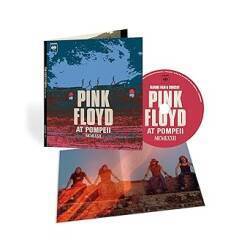

Pink Floyd and the Amphitheatre

The concert film Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii had been filmed in 1971, released in 1972, extended and re-released in 1974, and a Director's cut was released in 2002. Then, shortly before my return to Italy in 2025, a 4K restoration retitled Pink Floyd at Pompeii — MCMLXXII became an international sensation.

I came in through the entrance nearest the train station, at the southeast corner of the publicly accessible area and nearest the amphitheatre.

Well, "concert film", sort of. The filmed performance in the amphitheatre featured a typical concert set list of that period, but it was just the band and a small crew in the amphitheatre. (plus, unseen in the film, a small number of local kids)

Yes, some aspects of amphitheatre and stadium architecture have changed little over the past two millennia.

Men were working on the amphitheatre floor. Only some of the seats remain or have been restored, red poppies fill the gaps.

The amphitheatre was built in 70 BC and could seat up to 20,000 people, meaning that patrons came in from outside the city.

A special exhibit in a passageway beneath the seats documented the band's members and projects in the early 1970s and the creation of the film.

Left to right: Richard Wright, Roger Waters, Nick Mason, and David Gilmour.

Pink Floyd's 1971 concert was the first performance in the amphitheatre in almost 1,900 years.

Then in July 2015, 44 years later, David Gilmour played a concert there as part of his tour supporting his Rattle That Lock album. Following that, in July 2023, Nick Mason and his Saucerful of Secrets band played a concert here.

Casa di Octavius Quartio

I did not remember seeing this house or anything like it during my 2009 visit, Gardens and an elaborate water feature have been restored, and the house has some very nice frescos.

Via dell'Abbondanza

Via dell'Abbondanza is one of the main east-west streets through Pompeii.

An area along the north side of Via dell'Abbondanza that had been buried in 2009 was now being scientifically excavated and analyzed, and the public can watch from overhead walkways.

a.k.a. Santorini

It reminded me of what I saw at the Akrotiri site on Thira, commonly known as Santorini, with public walkways above science down below. And look, amphorae stacked along the walls of a room.

Much has been excavated, but much has not. On one hand, leaving an area buried will protect what's there from damage and oxidation. But on the other hand, an unexcavated rectangular block surrounded by the open spaces of excavated areas will, during the rainy season, become water-saturated and it might collapse outward, destroying everything within. There's no simple right answer for protecting the site.

Into an Elite Home

Looking through the entryway to an elite home on the south side of Via dell'Abbondanza, we see a large atrium with an open skylight. Below it is the impluvium, a nicely decorative pool but also a means of collecting rainwater for household use.

There were more explanations within the structures than what I remembered from my earlier visit.

Like many elite homes, this has a mosaic floor and frescos combining imagined scenes and optical illusions of furniture and windows.

Casa dei Ceii

Casa dei Ceii is along Vicolo del Manandro, a secondary east-west street. Its short entry hall opens into a large open-topped atrium.

A large room toward the rear has a large and elaborate fresco. An image of a fountain, at lower right, seems to have also been an actual source of flowing water that partially circled the room through the channel seen here.

Caca dei Ceii had a private latrine, located in a small room immediately inside the entrance. Come in through the outer door and the short entry hallway, then make a 180° turn to the left to enter this space. The remaining sign of the latrine is the hole in the floor near the far corner. A wide bench seat of wood or stone would have run left to right above it at the height you expect. That location made for easy connection to the municipal sewage drain running under the street. See my other travel-related site for more on the plumbing of Pompeii.

The Forum

The forum of a Roman city was its main square, containing a large marketplace along with political, economic, and religious facilities. Pompeii's Forum was originally built around the 4th century BCE, and then was expanded and completely rebuilt by the Romans, especially during the 2nd century BCE and then again in the 1st century BCE. However, it retained a distinctly Greek design, reflecting the city's origin as a Greek settlement. It runs roughly north-south, aligned with the peak of Vesuvius rather than true north.

The Romans were very unimaginative, copying everything from the Greeks while just making up new names in Latin. Also, the Æneid is nothing but Virgil's fan-fiction.

The Temple of Jupiter stands at the northern end. Jupiter is the result of the Romans re-naming Ζεύς or Zeus, the Greek Sky-Father, the King of the Gods. The temple was built in 150 BCE while the Temple of Apollo was being renovated. In the process the Roman Jupiter was replacing the Greek deity Apollo, and the Temple of Jupiter became the city's primary temple.

The temple was mostly destroyed in the 62 CE earthquake, and was still being rebuilt when Vesuvius buried it in 79 CE.

The Basilica extends off the southwest corner of the Forum. But no, this isn't a Christian church.

Basilica is a term of architecture, from the Greek βασιλική στοά or just βασιλική, basiliki. That's a public building in a rectangular shape, divided by internal rows of columns supporting roofs of differing heights. Courtrooms would be there, but more, like how a courthouse in an English-speaking country would contain some court chambers but also various government offices. Today you might go to the courthouse to renew a driver's license, pay your city utility bills, vote, get a construction permit, or do other tasks with no judges or lawyers involved. The same with a basilica in the past.

The central section, under the highest roof, is the nave, from the same root as naval (it's the Big Ship of Government), while the outer aisles between the column rows and the outer walls are probably under lower roofs. clerestory windows in upper walls joining the roofs could provide more light for the interior.

It was a useful design, construction workers could build it and the public was familiar with it, so churches adopted it. At some point the Roman Catholic church started to use the old word "basilica" to designate churches given privileges to carry out certain rituals.

In this basilica-in-the-original-sense structure, the front end contained a raised platform like a stage, where officials might deliver speeches or make official announcments.

The Sanctuary of Apollo is across the Via Marina from the Basilica. It was first established in the 8th or 7th century BCE, as an open area with multiple altars. Its first building was constructed in the 6th century BCE.

Apollo was the most venerated deity of Pompeii, and this temple was the city's primary religious center, contained within a sacred enclosure.

Forty-eight fluted columns formed its outer perimeter.

Within that, a staircase led up to a high podium or elevated platform, which was encircled by twenty-eight smaller columns.

Within that was the ναός or naos, the innermost chamber containing the cult image or statue representing the eity.

Greek temples almost always centered the naos within the overall temple plan. This one was rebuilt under Roman influence, and the Romans called the naos a cella and usually shifted it toward the rear of the structure, as they did here.

The Naughty Bits — Lupanare and the Erotic Art

At least it wasn't yet the Victorian Age, but the northwestern Europeans were thoroughly scandalized by some of what they found at Pompeii. Some of the artwork was erotic, and then there was what came to be called the Lupanare, a brothel named after the purported "she-wolves" who worked there. Because it's always the women's fault.

I saw it during my 2009 visit, but it was closed when I returned in 2025.

Most brothels in Pompeii were single-room operations. The Lupanare was the largest, with ten rooms. The beds look awfully uncomfortable, as all that survives today is the solid stone bed form and "pillow". There would of course have been mattresses and pillows on top of this!

The book "Cities of Vesuvius: Pompeii and Herculaneum" (Michael Grant, 1971) quotes the earlier "Present State of Pompeii", by Malcolm Lowry, 1949: "The brothels were by no means spacious and 'seemed to have been made to accommodate the consummations of some race of voluptuous dwarfs'."

In other words, the beds are rather short.

The brothels has erotic frescos. Perhaps they were a graphical menu of available choices. "I'll have Number 3, please."

All of the erotic and fertility related imagery shocked the excavators and early influential visitors. Some discoveries were re-buried and then re-discovered in later years. A large collection at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples was inaccessible without academic credentials or special permission until 2000.

Graffiti on the walls of the Lupanare indicates that the prostitutes were slaves from all around the Mediterranean.

See Ronald Reagan's repeated use of the phrase "strapping young bucks" to describe Black men as dangerous sexual predators.

The frescos show that there's nothing new in the way of stereotypes. They intentionally depict the women with significantly lighter skin, despite their origins, and the men with significantly darker skin. The theory was that lighter skinned women were more beautiful, and darker skinned men were more sexually active.

Fleeing by Ship

Pliny the Elder famously sailed straight into danger, crossing the Bay of Naples from Misenum to Pompeii. He is credited for having coined the phrase "Fortune favors the bold" while doing so, despite a complete lack of evidence that he said anything like that.

I also sailed across the Bay of Naples, but in a direction perpendicular to Pliny's. I was on board the MS GNV Antares, a 31,598-tonne ferry running the overnight route between Napoli and Palermo, on Sicily. But I still kept a close eye on Vesuvius. There it is, east of our berth in the Napoli harbor.

Above and below, those small dark wisps are simply clouds formed by the passage of air up and over Vesuvius. Not hot gases lofting an ash plume. I would see that later in the trip at other volcanos, but less dangerous ones, not Vesuvius, thankfully.

Notice the structures, including homes, built up the lower slopes of that dangerous volcano!

Yes, I was there.

We pulled away from the dock a little after our nominal departure time of 2000. By 2030 we were leaving the inner harbor with a seagull escort.

By 2120 we were well south-southwest of the harbor, on a course to pass to the west of Capri which itself is west of the Sorrento peninsula. Vesuvius was still clearly visible, forty kilometers to the northeast.

Where Next In Italy?

( 🚧 = under construction )

In the late 1990s into the early 2000s I worked on a project to

scan cuneiform tablets

to archive and share 3-D data sets,

providing enhanced visualization to assist reading them.

Localized histogram equalization

to emphasize small-scale 3-D shapes in range maps, and so on.

I worked on the project with Gordon Young,

who was Purdue University's only professor

of archaeology.

Gordon was really smart,

he could read both Sumerian and Akkadian,

and at least some of other ancient languages

written in the cuneiform script.

He told me to go to Italy,

"The further south, the better."

Gordon was right.

Yes, you will very likely arrive in Rome,

but Italy has domestic flights and a fantastic train system

that runs overnight sleepers all the way to

Palermo and Siracusa, near the western and southern corners

of Sicily.

So, these pages are grouped into a south-first order,

as they should be.

See letter VI:XVI To Tacitus, Letter 16 from the Sixth Book of Letters of Pliny the Younger.