Arriving in Taormina

Arriving by Train in Taormina

VisitingMessina

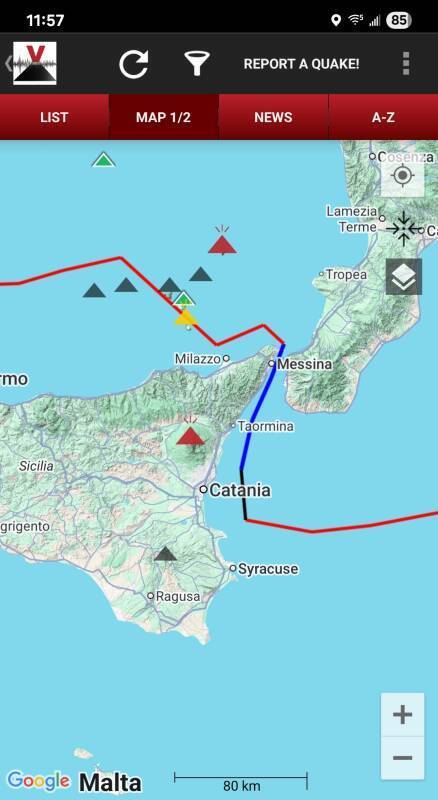

I had been in Messina for a few days. Then I rode a train south to Taormina. The rail line running along the coast from Messina reached Taormina in 1866, and extended further south to Catania the following year. It's now a quick ride from Messina to Taormina.

Segment of 1:500,000 aeronautical chart TPC G-2B showing the coast from Messina to Taormina, from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

Here's a Regionale train in Messina Centrale station, prepared to depart for Taormina, Catania, and Siracusa.

The Taormina-Giardini station is down by the waterline. Several of the English- and German-speaking passengers disembarking with me were already in their Taormina garb — white linen outfits with multiple wicker suitcases. One needs backup white linen outfits to wear while the hotel valet gets the red sauce out of what one wore at lunchtime.

Not everyone in the station was arriving in white linen and wicker. But it was still a classy joint.

Getting to the old town involves an ascent of about 250 meters along twisting roads. My Booking.com innkeeper had told me that she could arrange a private car transfer from the train station for €85. Or, there is a bus for €6.50. I told her that I would take the bus. It turned out to cost only €1.10. From what I later saw around the two top hotels, I assumed that quite a few full-price private car rides are arranged.

I walked through the station to wait for the next bus. They ran every 20–30 minutes.

Yes, the town seems be very close to the water when you look at a 2-D map. But if you turn on terrain relief, which Google Maps doesn't support in embedded maps, you see how much of a climb is involved. You can also see how the E45 express highway runs far beneath Taormina in a deep tunnel.

To My Apartment

I walked about a hundred meters up the road from the bus lot, against the pedestrian stream of day-trippers on their way out.

Vulcano,H2S, and SO2

Vulcano smelled of hydrogen sulfide. The road in front of my place here smelled of burning clutch plates because of the twisting steep climb from the coast road.

My apartment was in a structure built to conform to the steep slope behind it. It was above a closed gas station café and mini-mart. The apartments were accessed by the steep ramp at left here. My apartment was €55/night, the highest for this trip but way below most accommodations in Taormina.

It was the usual Booking.com experience. I never met my innkeeper, she told me how to get in on my own. There were ten proper mail boxes by the outer door, ten actual residences. Then, fifteen keyboxes of varying but similar design, each with a four-digit tumbler lock for visitors like me. She described her keybox and its four-digit combination, and inside was a pair of keys. One for the outer door into the building, and the other for the apartment.

Turning to look back before entering the building, there was a nice view over the gas station café roof to the Ionian sea coast up toward Messina.

It was a windowless one-room apartment against the cliff on the back side of the building. The all-or-nothing lighting, controlled by switches at knee level, seemed adequate for performing orthopedic surgery. €55 in Taormina isn't going to give you a large balcony with a sea view. Or a white-linen-laundering valet.

It had a tiny kitchen, which the terrain constraints placed up a short set of stairs. The window in the far right corner actually opened into the washing area of the kitchen.

The far end of the kitchen compartment had a translucent ceiling at the base of a window well against the cliff.

Italian BidetsThe bathroom was beside the entryway, as commonly found in apartment buildings. Most accommodations in Italy have a standalone ceramic bidet. Of the twelve places I stayed on this trip, this and the similarly almost-windowless apartment in Salerno were the only two without a standalone bidet.

This one did have a hose with spray nozzle and flow and temperature control — shattaf in Arabic or taharet musluğu in Turkish, literally meaning "bidet faucet". Sorry, I don't know of any specific English term for the device.

The Greek Theatre

My innkeeper had left a note explaining a bonus of the location. If you went to the top floor of the apartment building, then up to the elevator hoist and out the back, a series of paths and sets of steps led up to the top of the ridge, where you were looking into the Greek theatre. So, as soon as I unpacked my stuff in the apartment, which took very little time, I headed up there.

The large Greek theatre is famous for its dramatic location, with Mount Etna as a distant backdrop. It was first built by the Greek colonists in the 4th century BCE. Then the Romans considerably altered it and then almost entirely rebuilt it in the 1st-3rd centuries CE. It is the second-largest ancient theatre in Sicily, after the one at Siracusa.

From the street in front of my apartment to the rear of the theatre is an ascent of about 60 meters. Up the steep ramp to the apartment building's entrance, up four more floors within it plus a floor and a half to the rear entry, and then up the paths and staircases.

Here's the ascent looking back down at each stage. First, a couple of levels above the roof of the building where I stayed, was a swimming pool that hadn't been used for some time.

At near right here is the two-story building overlooking that pool. Below that is the solid red tile deck around the pool. Further down, in direct sunlight, is the orange roof of the very top level of my building.

Stone and concrete staircases continued through switchbacks up the steep slope.

I finally reached the fence around the theatre.

To the Viewpoint for Etna

For a much better view of Mount Etna, I went down to the road and walked about 300 meters back down the road to a nice viewpoint. Belvedere di Via Pirandello if you're trying to find it. The view to the north from there was a little different from the view from the door into my building. That's the coast of Sicily on the left half of the picture. In the haze in the distance on the right half is the coast of Calabria, the "toe" of the Italian peninsula, about 35 kilometers away.

Isola Bella or "Pretty Island" is the barely-connected island at right here. Notice the freight train running north on the coast line between the road and the waterline.

The coast road runs out along the next small peninsula to the south. The rail line takes a shortcut through a tunnel underneath the peninsula.

The twisting road from the coast is behind the black line of arches. Two cruise ships are anchored off the modern city of Naxos in the distance. Mount Etna is in the further distance at right, barely visible through the late-afternoon haze.

I went down to the viewpoint multiple times each day to look for ships and see what Etna was up to. The air was much more clear in the evening of that first day.

Mount Etna was my initial reason for stopping in Taormina. Volcanos were a theme on the trip — Vesuvius, Vulcano, Stromboli, and now Etna. I stayed in Taormina for five nights to give the weather and Etna's activity a little more opportunity to put on a show. All the Taormina history I discovered gave me plenty to see and do in between checking for volcanic activity.

Etna is continuously active because it's above a convergent plate margin between the African Plate and the Eurasian Plate. The volcano first began forming about 500,000 years ago, when its present location was a large bay in the east coast of Sicily.

Lava and ash output built Etna into the tallest peak in Italy south of the Alps. By the time of my visit it had reached a height of 3,403 meters, but constantly varied with further eruptions and rapid erosion of ash layers. The below chart was compiled in 1962, when the official height was 50 meters less.

Segment of 1:500,000 aeronautical chart TPC G-2B showing Taormina and Etna. from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

Etna is considered a dangerous volcano today, but it used to be much worse. From about 35,000 to 15,000 years ago, Etna produced highly explosive eruptions. Ash from those eruptions has been found 800 kilometers to the north, close to Rome.

About 8,000 years ago, its eastern flank underwent a catastrophic collapse. It generated an enormous landslide and resulting tsunami that struck several places around the eastern Mediterranean. Maybe that had a huge impact on cultures, entering their mythology. Or maybe hardly anyone really noticed it.

An eruption in 396 BCE seems to have stopped the Carthaginians in their advance on Siracusa.

A leading theory is that its name comes from the Phoenician attuna, meaning "furnace" or "chimney". The Phoenicians settled Sicily before the Greek colonists began to arrive.

The Greeks called it Aítnē or Αἴτνη. Their mythology said that Zeus, the god of the sky and thunder, trapped the monster Typhon underneath this mountain, and the forges of Hephaestus were also down there. The Romans later came along and, as usual, simply made up Latin names for everything.

Now it's also known as Muncibbeḍḍu in Sicilian and Mongibello in Italian. Those are mash-ups of the Romance word monte and the Arabic word jabal or جبل, both meaning "mountain", so it's redundantly something like "Mount Mountain". Confusingly, Patricia Highsmith used "Mongibello" as the name of a fictitious town along the Amalfitani coast in The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Possibly even more confusingly, "Mongibel" appears in Arthurian romance as the name of an otherworldly castle or realm of Morgan le Fay and her half-brother, Arthur. But Arthur was originally a mythic figure in Welsh tales of early post-Roman Britons against the Anglo-Saxons in the late 5th and early 6th centuries. Not at all Sicilian.

But there is a roundabout connection. The Normans were originally Norse raiders who settled in northern France in the 900s. That area that came to be called Normandy. The Arthurian legends, originally Welsh, spread to Brittany, just to the west of Normandy. Breton entertainers then accompanied Normans in the 1000s as some invaded and conquered England while others sailed to Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula.

The Breton troubadors incorporated this huge dramatic volcano into the Arthurian tales, and then carried that back to Brittany, Normandy, and Norman-ruled England.

By the late 1500s, William Shakespeare was writing plays set in Sicily. Much Ado About Nothing was set in Messina, and The Winter's Tale and Antony and Cleopatra were set more generally in Sicily.

OK, that's more than enough esoteric digression. Time to look around Taormina.

Where Next In Italy?

( 🚧 = under construction )

In the late 1990s into the early 2000s I worked on a project to

scan cuneiform tablets

to archive and share 3-D data sets,

providing enhanced visualization to assist reading them.

Localized histogram equalization

to emphasize small-scale 3-D shapes in range maps, and so on.

I worked on the project with Gordon Young,

who was Purdue University's only professor

of archaeology.

Gordon was really smart,

he could read both Sumerian and Akkadian,

and at least some of other ancient languages

written in the cuneiform script.

He told me to go to Italy,

"The further south, the better."

Gordon was right.

Yes, you will very likely arrive in Rome,

but Italy has domestic flights and a fantastic train system

that runs overnight sleepers all the way to

Palermo and Siracusa, near the western and southern corners

of Sicily.

So, these pages are grouped into a south-first order,

as they should be.