Selçuk

Scenes around the town of Selçuk

Selçuk is a town of about 23,000 total population, 18 km inland from the seaport of Kuşadası and about an hour by bus south of İzmir.

Lots of people come to Selçuk, but almost all of them to visit Ephesus, Maryemana, and other nearby sites. Much of the town itself remains generally undisturbed and undeveloped, an interesting traditional Turkish town.

Here's a view from a table at one of the many places selling delicious pide, or Turkish pizza.

There are many places to get a meal or just a snack while watching the town go past. Many of the smaller streets at the center of town are pedestrian-only.

A Byzantine-era fortress overlooks Selçuk. The fortress is on Ayasoluk Hill, the dominant landform in town. Larger hills rise to the east.

Saturday market

There is a market in town every Saturday.

You can find plenty of fresh produce! The guesthouse where you are staying will frequent the local markets so they can prepare great meals.

You can get just about anything at the weekly market — food, clothing, shoes, tools, and much much more. Something for the kitchen, perhaps?

Aqueducts and Storks

When the Romans took over Ephesus over 2000 years ago, they built many aqueducts to carry water from the nearby hills to Ephesus, a distance of three to five kilometers. They re-used some of the blocks from earlier versions of the Temple of Artemis. So, the aqueduct crossing the center of town contains some blocks with carved writing, sometimes sideways or upside down as the blocks were put to use however they best fit.

The Romans are long gone, but the storks like the aqueducts.

Aqueducts, storks, backgammon, and tea. It's a typical quiet day in Selçuk. One tea house relies on the aqueduct!

Basilica of Saint John

In the early 500s, around the same time that the Haghia Sophia (in Turkish: Ayasofya or Aya Sofya) was being built in İstanbul, Justinian also directed the construction of a nearly equally enormous church over what was then believed to be the burial place of the apostle John. See the Ephesus page for more on John's presence in this area and a timeline. The basilica was built part way up the small hill overlooking the Temple of Artemis, just below where a fortress was built in later Byzantine times.

Back in those days, the town was named for John — Αγιος Θεολογοσ or Agios Theologos — the Holy Theologian, or Saint John the Theologian. The Ottoman Turks later modified and shortened this to Ayasluğ. The town was renamed Selçuk in 1914, after the Seljuk Turks who had settled throughout the region in the 1100s.

The Temple of Artemis was disassembled, with some of its columns being hauled north to Constantinople and the new Haghia Sofia. The remaining blocks were hauled up the hill to build the Basilica of Saint John.

In 1090 the Seljuk Turks conquered the area, and the basilica was largely disassembled and the stones moved down the hill to build the Isa Bey mosque (see below for more on that).

An organization based in Lima, Ohio, U.S.A., was attempting to rebuild the basilica. But the work was going very slowly and probably has now progressed as far as it ever will.

George Bertrand Weitzel was born in 1890 and then orphaned as a young boy. He was taken in by a young Roman Catholic priest, Francis M. Quatman, whose own father had died when he was just two years old. George took the priest's family name, Quatman.

George Quatman attended seminary and then college, going into a career in the telephone business and owning several independent telephone companies in Ohio. He founded the American Society of Ephesus to restore religious sites in Turkey. The Quatman family website has more about him.

Quatman's goals were first to restore the Basilica of Saint John on the hill above Selçuk, and then to restore the Basilica of the Virgin Mary in Ephesus.

The Quatman family website describes a series of religious visions George Quatman had. First, two in Rome, associated with the priest who had raised him. His third occurred during his first visit to Ephesus in 1954:

Of course there was nothing to see of the basilica because it had been disassembled and its stones used to build the nearby Isa Bey mosque. This was exactly how the basilica itself had been built by disassembling the Temple of Artemis and re-using its stones. Anyway, he had a vision of the Virgin Mary in the sky over Ephesus, which he saw as symbolizing her wish that the tomb and Basilia of Saint John, the Church of the Virgin Mary, and Mary's home at Maryemana or Panaya Kapulu be restored.

Another description in "House of Our Lady", a book published by the American Society of Ephesus in 1991, described that vision as happening over the city of Izmir, sixty kilometers or more to the north:

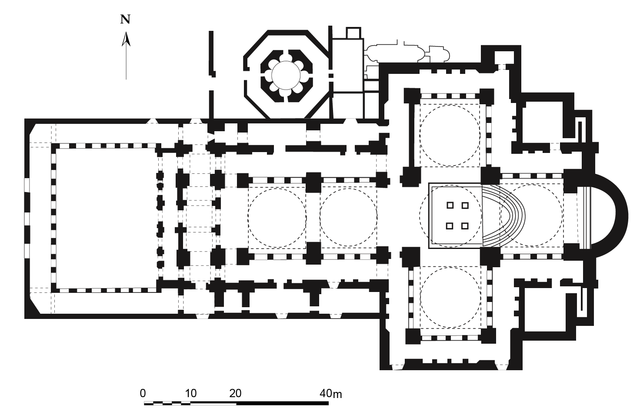

Floor plan of the Basilica of Saint John.

Amazon

ASIN: B01374B9PK

George B. Quatman died in 1964, and work was discontinued due to his death and the unsettled nature of the Turkish government. The government gave the society permission in 1973 to resume excavations and restoration.

The American Society of Ephesus, has a website, although it only contains very limited information. George Quatman's five sons were said to have carried on the work, but it seems that Joseph was the main force. He concentrated on restoring Mary's house and making it much more accessible and well known.

Joseph Quatman died in January 2011, and I wonder if that won't be the end of what has been a quixotic project of rebuilding two enormous churches (the Basilicas of Saint John and the Virgin Mary being about 130 and 150 meters in length, respectively).

Isa Bey Camii (Mosque)

The Seljuk Turks captured the region in 1090. This camii (or mosque) was built in 1375 by Isa Bey, the Emir of Aydın. That's a settlement today about an hour away by bus toward Denizli and the Mediterranean coast. The builders reused blocks from the nearby Basilica of Saint John. This means that these blocks are now part of their third religious facility over a span of the past 2500 years!

It is said to be built "in a post-Seljuk pre-Ottoman transitional style", if you are interested in detailed architectural chronology.

Anyone would notice that it resembles Seljuk structures from Konya or even mosques from Syria or Egypt much more than it does the stereotypical Ottoman mosques of İstanbul.

Notice the finely detailed geometric stone work of the main entrance.

The mosque is open for visits during most of the day.

Let's go in!

The outer gate leads into a large peaceful courtyard. The overall structure is divided roughly in two, half being enclosed as a mosque and the other half an open courtyard.

The front wall of the mosque, the direction toward Mecca, is the long wall opposite these doors. In the center of that wall just below the dome is the mihrab, the niche indicating the direction of Mecca. Beside the mihrab is the minber, the elevated pulpit from which scripture may be read or sermons preached. Below is a simple plan of the mosque and its courtyard:

+=================================+ || [===] || || ^ [ ] || || | ^ || || interior | | || || | minber || || mihrab (niche) || || || +==============|---|==============+ | doors <-- entrance | | | | | courtyard | | | | | +---------------------------------+

Tombstones are lined up along two sides of the courtyard.

Can you read the dates on any when you visit? Remember that you will need to read the Islamic calendar dates in the Arabic numerals used in Ottoman Turkish, and then add approximately 620 years to convert to the western calendar:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Western style "Arabic" numerals |

| ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ | Real Arabic numerals |

Here we're looking across the courtyard toward the main entry. The minaret has lost its peak.

The white stone mihrab is the niche indicating the direction of Mecca. To the right of the mihrab and partly obscured by the column is the minber, the elevated pulpit. As in most mosques, the floor is covered with a variety of carpets. They are donated by families or individuals for the improvement of the mosque.

Unlike Ottoman mosques, but like Mamluk or Seljuk mosques, the Isa Bey mosque is an elongated rectangle, much wider side-to-side than front-to-back. If you can't make it to Damascus, Cairo, or other points to the south and east, this is an opportunity to see some different architecture.

We're looking the opposite way along the front wall.

Why do you need to remove your shoes (ideally after washing your feet in the provided ablutions fountain) before visiting a mosque?

It's to keep the carpets clean! Prayers involve touching hands and forehead to the ground multiple times. Now really, would you want to put your forehead where people have been walking in dirty shoes?