Andy Warhol in New York

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol was one of the leading figures in the Pop Art movement of the 20th century. His paintings, although intentionally simple and based largely on techniques used for mass production, include some that have brought the highest purchase prices in history.

He started as a commercial illustrator and became quite successful working in the business world. He moved more into pure art in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and starting in the mid 1960s began to explore the connections between commercial illustration, art, popular music, and the ever-increasing fixation on celebrities in American life. His art work included painting and printmaking, as well as photography, film, and performance art.

Rob Pruitt's "The Andy Monument" (2012) was installed for a while outside the 1973–1984 location of Andy Warhol's Factory at 860 Broadway.

Origins in Eastern Europe

Andrej Varhola was born in August of 1928 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His parents were from Mikó, now called Miková, in territory that is now the Stropkov District of northeastern Slovakia.

Until 1918, Mikó was part of the county Sáros in the Kingdom of Hungary, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was within Upper Hungary, or Felivdék in Magyar, until the region was transferred to the newly formed country of Czechoslovakia in 1920 when the Treaty of Trianon redefined the post-World-War-I boundaries of Hungary.

The Varhola family were Lemki, Orthodox Christian people who called themselves Лемки in Ukrainian or Лемкы in Lemki (which may be a language in its own right or simply a dialect of Ukrainian). They also call themselves Rusyny, Русини in Ukrainian or Руснаки in the Lemki language or dialect. They come from the western Carpathian mountains along today's border between Slovakia, Poland, and Ukraine. A Lemko-Rusyn Republic declared its independence in 1918 before being incorporated into Poland in 1920.

Ukrainian linguists consider the Lemko language to be the westernmost Ukrainian dialect. Others classify it as the westernmost dialect of the Rusyn language, sometimes called Ruthene or Ruthenian by English speakers. The arguments seem to be much more political than linguistic. "Lemko" comes from the characteristic word лем or lem which they, unlike their neighbors who speak closely related languages, use to mean "but", "only", or "like". Surrounded by speakers of other related languages, Rusyn varies from one area to another and has never been standardized.

The Varhola's first child died in Mikó/Miková before they moved to the U.S. Andrej's father, also named Andrej, moved to Pittsburgh in 1914. His mother, Júlia, followed in 1921. Three sons were born in Pittsburgh: Pavol (later known as Paul) in 1922, Ján (later known as John) in 1925, and Andrej in 1928.

Andrej Varhola later changed his name to Andy Warhol and became a hugely influential figure in American art.

Arrival in New York

Andy Warhol graduated from high school in 1945 and then studied commercial art and illustration at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Paris. he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts and moved to New York City where he began a career in pictorial design, working in the advertising field.

He became a prominent commercial artist, working in a loose style that continued when he adopted silk screen print making. Both his commercial and artistic work was intentionally rough and imprecise. He wrote, "When you do something exactly wrong, you always turn up something."

Around 1954–1956 he lived in a four-story walk-up at 242 Lexington Avenue on the corner of 34th Street. It was probably on the northwest corner, where today the Santander Bank is the ground floor of a relatively new apartment house. He had a studio there, and there was room for his mother to also live there.

In August 1960 he moved uptown, from 242 to 1342 Lexington.

The five-story house at 1342 Lexington Avenue is just north of 89th Street. It's just 16.5 feet wide. It was designed in 1889 by Henry Hardenburgh, the architect who also designed the Plaza Hotel and the Dakota apartment building. Warhol bought the structure for about \$60,000 and moved into it with his mother.

The white building is on the corner of Lexington and 89th Street. Warhol's home at #1342 is the brick building with the angled roof line just to its north, to the right as seen from Lexington. We see it here on a day that a street fair had taken over Lexington.

Warhol used the ground floor as his studio in the early 1960s. In the 1950s and into the early 1960s he first began exhibiting his work and then started creating his iconic art, much of it featuring celebrities and household goods. He made a significant point about the social effects of commonly available low-cost commercial products when he wrote:

Warhol lived in the house until 1974. He then leased the house to his business manager, who later purchased it from the Warhol estate.

In 1962, 457 West Broadway, just south of Houston, was home to the Active Process Supply Company. Warhol had screens made there. Now it's Martin-Lawrence Galleries.

Founding "The Factory"

Warhol had begun using assistants to increase his productivity when working on advertising illustrations in the 1950s. He continued to collaborate, even turning work over to assistants, throughout his career. When prints are created through a silk screen process, who really creates the work — the person who creates the screen itself, or the person who operates the printing process?

He had started this collaborative operation while still operating out of the ground floor of his Lexington Street home.

Then, in 1962, he rented a space on the fifth floor of 231 East 47th Street. A speed freak named Billy Linich lined the space with aluminum foil and spray-painted everything silver. It came to be known as the Silver Factory.

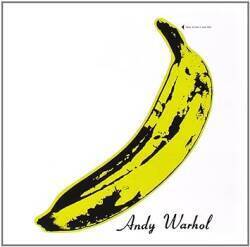

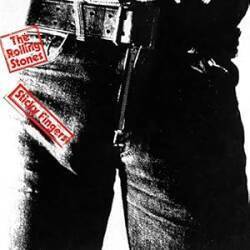

Warhol collaborated with other artists and musicians during this time. He designed the album covers for Lou Reed's band The Velvet Underground and Nico and for the Rolling Stones' Sticky Fingers. Stickers, zippers, simple designs with unexpected physical complexity.

Lou Reed's best known solo song, Walk on the Wild Side, is based on the "Superstars" Warhol gathered at The Factory. Some of them were creating artistic work but many of them were gathered there simply in hopes of their creating a more artistic atmosphere.

By 1968, the building was scheduled for demolition and replacement by an apartment building. The Factory was moved south, to the west side of Union Square just south of 17th Street.

In 2013, as you see here, there is no building above ground at 231 East 47th Street. The address is somewhere above the top of a parking facility.

Soon after the first Factory was established, on 21 December 1962, Andy signed a $150/month lease on an unused 2-story firehouse at 159 E 87th Street between Third and Lexington, to be his personal gallery. In 2022 it was still an art gallery.

Move to Union Square

Warhol moved The Factory to the sixth floor of the Decker Building in 1968. That's the right-hand one of the two tall and narrow buildings seen here, the slightly less tall and perhaps more ornate one. It's at 33 Union Square East. It mixes influences of Venetian and Islamic architecture, which included a minaret on the roof until its removal some time before World War II.

The Decker Building was constructed in 1892 for the Decker Brothers Piano Company, following the design of John Edelmann, an architect who was also a socialist-anarchist. He had been expelled from the Socialist Labor Part for being too much of an anarchist, so he and some like-minded anarchists founded a more anarchist Socialist League in 1892 as this rather capitalistic tower was being built. The following year, 1893, he and other radicals published the anarchist journal Solidarity. When it folded, as anarchist journals tend to, he sent articles to The Rebel, based in Boston. This brought him into contact with Emma Goldman, a prominent American anarchist and writer.

Speaking of anarchists and other radicals, one of the more marginal Factory figures was the radical feminist writer Valerie Solanas, whose 1967 S.C.U.M. Manifesto advocated the elimination of all men. She had appeared in one of the many films Warhol had shot at the Factory in its 47th Street location.

One day in July of 1968 she appeared at this new Factory location to demand the return of a script she had given Warhol. The script had been misplaced, and she was turned away.

She returned and shot Warhol and the art critic Mario Amaya. Amaya was only slightly injured, but Warhol was seriously wounded and barely survived. This was the end of the "Factory 60's". Warhol said:

Increasing Commercialism in the 1970s and 1980s

In 1973 Warhol moved the Factory less than one block to the north along the northwest edge of Union Square, to 860 Broadway at 17th Street. It was above what was a pet supply store when I took these pictures.

This was a larger space, but the experimental film-making was mostly over.

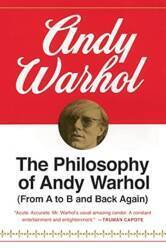

Warhol had been interested in the most exotic fringe characters among his "Superstars" in the 1960s, emphasizing decadence, orgies, drug abuse and scandal. In the 1970s he became quite business oriented. He founded Interview magazine and in his 1975 book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol he wrote:

He began concentrating on commissioned work for wealthy patrons, including the Shah of Iran and the very top figures in popular music.

By the end of the 1970s some critics were dismissing him as a "business artist", complaining that his portraits of celebrities were superficial and commercial.

Other critics said that it was precisely Warhol's superficiality and commercialism that captured American culture and were "the most brilliant mirror of our times."

A number of businesses occupy the former Factory space at 860 Broadway today, but none of them look especially artistic.

Unless, of course, that architectural firm is full of anarcho-socialists.

In 1984 Warhol moved out of the Broadway Factory location, occupying two locations on either side of the southwest corner of Madison Avenue and 33rd Street.

The last Factory location was at 22 East 33rd Street, behind the blue fencing seen above. The building had been demolished and the lot had been empty for a while when I took these pictures.

Andy Warhol's last personal studio was around the corner at 158 Madison Avenue, just south of 33rd Street. That building has been torn down even more recently, after January, 2013, when I took the pictures of the last Factory location, but before September, 2013, when I took the picture below.

The impermanence of Warhol's studio locations seems to fit together with his 1968 prediction:

In 1966 he had filmed a number of acquaintances without providing any script or direction, creating the film Chelsea Girls. This was a three-and-a-half hour film of his entourage conducting their daily life in eight rooms of the Chelsea Hotel. According to the Radio Times Guide to Film 2007, "Andy Warhol's underground film is to blame for reality television."

Well, the plague of "reality" television filled with human garbage probably would have happened without Andy Warhol's assistance. But he was keenly aware of our culture's obsession with fame. Polls of children and even adults demonstrate that when you ask many Americans "Whom do you most admire?", you really get an answer about who is the most famous or notorious, with those two concepts becoming ever more blurred. The U.S. eventually elected a serially bankrupt "reality" television figure as its President.

I don't think that Warhol was saying that fame or notoriety for its own sake is a good thing, or that such nonsense should be encouraged. I think he realized, and was willing to say (and why not take economic advantage of saying this while you're at it) that fame, even the pointless variety, does have an enormous influence in popular society.

Andy Warhol's last home was at 57 East 66th Street on the Upper East Side.

He was living here when he died in February, 1987. He was making a good recovery from routine gallbladder surgery when he died in his sleep from cardiac arrhythmia. After being shot in 1968, the emergency care surgeons had had to open his chest and massage his heart to stop its fibrillation and stimulate its continued function. He was never in great shape after that.

Almost all of his estate was auctioned by Sotheby's to fund the founding of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Influence on Music

As described above, Warhol involved many musicians in his Factory. Lou Reed and John Cale, prominent members of The Velvet Underground, were two prominent musicians associated with the Factory.

The Velvet Underground was first active from 1964 to 1973, and was one of the most influential groups of the period. It was also the house band at the Factory. Warhol is described as the band's "manager" or "producer", but his support was mostly financial and encouraging, not musical. He did insist that the German singer Nico join the band for three songs on their debut album, which was titled The Velvet Underground and Nico, and he did design the album's cover.

Band members lived and recorded at 56 Ludlow Street on the Lower East Side in 1965. Here we're looking north on Ludlow Street from Stanton Street, past the restaurant El Sombrero which the locals (and eventually its owners) called "The Hat".

Warhol's personal preference was much more for glamour than for grit. He frequented Studio 54 when it existed from 1977 until 1981 as a world-famous nightclub catering to a world-famous clientele.

The Studio 54 nightclub was located at 254 West 54th Street, between Broadway and 8th Avenue. The building originally housed the Gallo Opera House in 1927, later changing hands multiple times before becoming CBS radio and television Studio 52 from 1940s until the mid 1970s. Captain Kangaroo was among the shows created there. CBS moved out in 1976, relocating to the Ed Sullivan Theater just around the corner on Broadway and the enormous CBS Broadcast Center on West 57th Street between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues.

It was converted to a large and opulent nightclub, opening in 1977 and featuring the current craze of disco music and novelties like a layer of glitter four inches thick on the floor at New Year's Eve.

Its original nightclub incarnation closed in February of 1980 as the owners, Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, had confessed to tax evasion and spent 13 month in prison. They sold the building in 1981 but kept a lease, then it quickly sold again and they stayed on as consultants.

It reopened in September, 1981, and rising stars including Madonna, Duran Duran, Culture Club and Run-DMC performed at the club. During the 1980s its focus drifted briefly through heavy metal, then Latin dance. From 1988 through early 1993 its name changed to The Ritz and it functioned strictly as a concert venue for Punk, New Wave, and Eurodisco performers. Then it was briefly back to "Cabaret Royale Studio 54" until early 1995.

Since 1998 it has been used for theater productions. A cabaret and restaurant calling itself 54 Below now operates in the basement. You can see its small red awning in the picture above.

Around this same period when Studio 54 was at the peak of its popularity, The Mudd Club operated a few blocks south of Chinatown in Lower Manhattan.

We're looking down the entire length of Cortlandt Alley, the only alley like this in all of Manhattan. Film makers and photographers use the area heavily as there are very few locations like this in the city.

In this picture we're looking south across Canal Street, the major east-west thoroughfare crossing Manhattan from the Holland Tunnel leading to New Jersey to the Manhattan Bridge leading to Brooklyn.

Cortland Alley ends at Water Street. The six-story brick building at the far end is #77 Water Street, the site of The Mudd Club.

The Talking Heads referenced the Mudd Club in their song Life During Wartime. The Ramones mention it in The Return of Jackie and Judy. Nina Hagen mentions it in New York / N.Y. Frank Zappa made fun of it in Mudd Club. The B-52s' first New York concert was at the Mudd Club.

The Mudd Club was a center for Punk and "No Wave" music, and it was patronized almost exclusively by that crowd when it first opened. It was intended to be an antidote to the "uptown glitz" of Studio 54 and similar glamourous nightclubs.

However, as its popularity grew during its first year or two of operation, "uptown celebrities" like David Bowie and Andy Warhol began frequenting The Mudd Club.

The building was constructed in 1888. It, and thus the club it housed, were named after Dr Samuel Alexander Mudd, the physician who treated John Wilkes Booth after he injured himself escaping from his assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Now gentrification has cleaned up the grittiness of the late 1970s in New York.

Who Was Andy Warhol?

It's hard to say just who Andy Warhol was. He was notoriously vague in interviews. While he was fascinated with the concept of celebrities, and with several of the celebrities themselves, he was an intensely private man. His devout religious faith came as a surprise to many who only learned of it after his death.

Rob Pruitt's 2012 sculpture The Andy Monument was installed for a while outside the 1973-1984 Factory location at 860 Broadway.

Its highly reflective metallic finish references the Silver Factory, the original dedicated Factory space.

In his later years he came to favor fright wigs. He was still producing these self-portraits a few months before his death.

Many museums display works by Warhol. The Baltimore Museum of Art has a significant collection of Warhol's works and has hosted special exhibits of some of his art. The pictures below are from a BMA gallery.

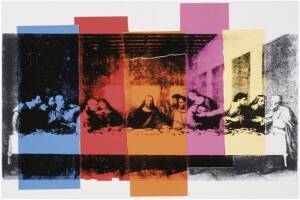

The picture above, also seen at the top of this page, is one of Warhol's re-imaginings of Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper.

He created almost 100 variations on the theme of this one image. This 1986 cycle of works was his last major collection of artworks. He had been commissioned to create a group of works based on the 1495-1497 original, to be displayed across the street from the original in Milan, Italy. He far exceeded the requirements of the commission in a near obsession with the topic. The exhibit of this final cycle of works opened just one month before his death.

His 1984 Details of Renaissance Paintings series had also depicted religious subjects, and a large body of largely unknown religious themed artworks was discovered when his estate was auctioned.

Yet another surprising contradiction of Warhol's life is that he kept the Eastern Rite Ruthenian Orthodox faith of his family, and kept a homemade altar with a crucifix and a well-worn prayer book beside his bed.

Church of St Vincent Ferrer, where Andy Warhol visited and prayed daily. Lexington Avenue at 66th Street.

The priest at Saint Vincent Ferrer's Church on Lexington Avenue at East 66th Street on the Upper East Side reported that Warhol visited almost daily, coming in mid-afternoon to light a candle and pray for a quarter of an hour. He was intensely private about his faith, keeping to himself and being self-conscious crossing himself as he did it in the Orthodox way (thumb, index and middle fingers touching, hand moving right to left) as opposed to the Roman Catholic fashion of the other parishioners.

The British art historian John Richardson said the following in his eulogy for Warhol:

The Revelation special exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 2022 focused on Andy's spiritual side. With material borrowed from the museum in Pittsburgh, the exhibit included his certificate of baptism and confirmation:

One of his works, shown above, combined his deep interest in simplistic commercial art, repetition, and religious themes.

A photo at the special exhibit showed Andy and three other contemporary artists crowded into Andy's bathroom. Notice the crucifix above the mirror.

Andy's mom lived with him until she died. He included her in some self-portrait works:

He described meeting Pope John Paul II as one of the thrills of his life.

Two of his large Last Supper pieces were in Brooklyn for the show.

Andy's Saint Mary's Catholic Church of the Byzantine Rite is on East 15th Street at Second Avenue in the Gramercy Park area. That's catholic in the original sense of the word, nothing at all to do with Rome or the Latin language.

Back to the Travel Recommendations