William S. Burroughs in New York

William S. Burroughs

William Seward Burroughs

was one of the earliest members of the "Beat Generation"

authors.

He was born in Missouri and died in Kansas, and was said

to always sound like a Midwesterner, but he famously lived and

wrote in New York and Paris

as well as more exotic locales such as

Tangier.

Most of his writing was simultaneously surrealist and

autobiographical, which immediately tells you something

about him.

Here are pictures and stories of the places where he lived

and hung out in New York, covering the period from when he

first took up residence there in 1939 through his

"Bunker years" of 1974-1981.

Burroughs is usually described as a famous author,

but his notoriety for drug abuse and addiction plus

open homosexuality in his life and writing may be how

his name are known to so many people who have never,

and would never, read anything he wrote.

Naked Lunch

is his most famous work.

Read the appendices first.

Otherwise there are long stretches that seem to be

little but shocking bizarreness for its own sake.

Start at the end.

Why not, the book is intentionally non-sequential.

"Oh, he was adamantly opposed to the death penalty, and

that's

why there's a long satire of executions

which is intended to criticize the system."

Not a Hagiography

You aren't going to find a fawning Burroughs hagiography here. He and his writing are interesting in a lurid can't-look-away fashion. Yes, he wrote some things that hadn't been written before, but with some of them it's not at all clear to me that we're enormously better off for their having been written.

Give me Hunter S. Thompson any time for surrealism, caustic satire of society and politics, and pharmacological misadventures.

Both Burroughs and Thompson wrote about writing. Burroughs wrote confidently about the processes of writing and getting published in some essays in The Adding Machine. Thompson wrote quite a lot about writing, especially about its difficulty. The thing is, it seems to me that Burroughs' meta-writing about writing reads like he was an extremely successful writer, while Thompson's reads like he never completed anything. But to my tastes, Thompson was a much better and more successful writer. Burroughs was a serial self-plagiarist. Much of his fiction is the same content over and over, maybe slightly re-mixed but often simply repeated from earlier works.

As for the drugs, Thompson was a connoisseur of chemicals while Burroughs was simply a heroin junkie for long stretches of his life. Burroughs was known as the Gentleman Junkie and the Pope of Dope. But read Junky to learn how that really turned out for him.

The Yagé Letters was OK as a travelogue through South America in the 1950s. Burroughs spent months looking for ayahuasca or yagé. That was before the preparation of a psychoactive brew was fully understood. The native people knew that a second plant, Banisteriopsis caapi to botanists, was needed. That second plant contains a monoamine oxidase inhibitor or MAOI, needed to make the result orally active.

Now there's a booming business in ayahuasca encounter travel for English speakers. Wade Davis beats everyone on participatory scientific ethnobotany.

Burroughs' Background

William S. Burroughs was born in Saint Louis, Missouri, in 1914. His grandfather, William Seward Burroughs I, was an inventor and founder of the Burroughs Adding Machine Company, which became the Burroughs Corporation and continued to produce office equipment after the technology had changed from purely mechanical to digital. His uncle, Ivy Lee, was a prominent early advertising executive and later worked as a publicist for the Rockefellers. His family was socially prominent in early 20th century St. Louis, and he later had a number of surprising encounters with prominent figures outside his immediate field. William Donovan, Alfred Kinsey, and more.

His parents sent him to the Los Alamos Ranch School, a boarding school described as a place "where the spindly sons of the rich could be transformed into manly specimens." In Burroughs' case it did not work out as intended. Los Alamos was an obscure mountain settlement when Burroughs was there in the 1920s. During the early to mid 1940s, Los Alamos was where the U.S. and developed its first atomic weapons, and Los Alamos National Laboratories is still one of the major Department of Energy facilities.

Burroughs was supported by a monthly allowance from his parents until he was at least in his 40s, and they were very comfortably well-off. However, they weren't as vastly wealthy as the label "heirs to the Burroughs fortune" makes them sound. His parents sold the rights to his grandfather's inventions, and sold all their stock in the Burroughs Corporation for $200,000 shortly before the 1929 stock market crash.

Burroughs attended Harvard University from 1932 through 1936, earning a degree in English. He worked during the summers as a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, where he was tasked with unpleasant assignments like the accidental deaths of children. He was writing about gruesome topics and building a disdain for authority, trends that continued through his life. During the Harvard school years he frequently traveled from Cambridge, Massachusetts to visit New York City.

After graduation from Harvard in June 1936 he made an extended trip to Europe, hanging out in the steam baths of Vienna and Budapest. He enrolled in medical school in Vienna, which lasted six months during which he was treated for syphilis he had picked up at a brothel in Cambridge and then had an emergency appendectomy.

Returning to Dubrovnik for recuperation, he again met Ilza Klapper, a Jewish woman trying to extend her visa to remain in Yugoslavia and flee Nazi oppression. Burroughs married her in July 1937, vastly helping her visa situation, by taking her to Athens where the American consulate set up the paperwork and found a Greek Orthodox priest willing to marry them. He soon returned to Vienna. She eventually made her way to the U.S. — while she and Burroughs were divorced, they remained good friends.

Burroughs soon returned to the U.S. and enrolled in graduate school at Harvard. He took courses in the Navajo language and Mayan archaeology. He stayed there until spring 1939, when he moved to New York and the start of this virtual tour.

1939 — Taft Hotel

Burroughs had a room at the Taft Hotel on Seventh Avenue just north of Times Square. The 22-story hotel fills the block of Seventh Avenue from 50th Street to 51st Street. It's now the Michaelangelo Hotel, the larger portion of the hotel is a 440-unit condominium and the smaller portion is a hotel.

Burroughs was introduced to a man named Jack Anderson (not the muckraking columnist, mind you) and immediately took him to his hotel room to have sex. They left the door unlocked, and a hotel employee going up and down the halls checking that the doors were locked saw them together in bed naked. The house detective and hotel manager arrived ten minutes later and told Burroughs he had ten minutes to pack his stuff and come downstairs for a refund for the remaining prepaid nights.

This was an inauspicious start that soon went further downhill.

Burroughs' obsession with Jack Anderson led to him severing the last joint of his left little finger in a bid for attention, an episode described in his short story The Finger. Writing inspiration aside, his parents became very concerned about his mental condition and pressured him to return to St. Louis.

World War II had been underway since September 1939 and U.S. involvement was looming. He tried to enlist in the navy but failed the physical due to bad eyesight and flat feet. He then tried the American Field Service, which had operated ambulances during World War I and would again in the coming war. But he was turned down for ambulance service when his interviewer, also a Harvard man, decided that Burroughs hadn't belonged to the right clubs or lived in the right fraternity while at Harvard.

He had an introduction to Colonel William Donovan, who would form and lead the O.S.S. However, Donovan's director of research and analysis had known and disliked Burroughs at Harvard, and rejected him.

So, unlike Jack Kerouac, who actively avoided military service, at least Burroughs repeatedly tried to serve.

1941 — West 11th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenue

His father got him a job as a copywriter for an advertising company in New York. In 1941 he was living with Jack Anderson in an apartment on West 11th Street between Fifth Avenue and Sixth Avenue. It's not clear exactly where the apartment was, but these pictures show that stretch of West 11th Street.

In 1942 he enlisted in the U.S. Army and was accepted, but as a soldier in the infantry, not an officer. His parents convinced a neurologist who was a family friend to declare him psychologically incompetent. Burroughs spent five months at Jefferson Barracks outside St. Louis, then moved to Chicago and had a variety of jobs. Most prominently as an exterminator, as he described in a story collected in the volume Exterminator! and portrayed in Cronenberg's movie Naked Lunch.

1943 — 69 Bedford Street

Two of Burroughs' friends from Chicago moved to New York, and he soon followed. The two friends were Lucien Carr and Dave Kammerer. Carr had been a student at the University of Chicago. Kammerer was an older man who was sexually obsessed with Carr and had followed him from school to school, continuing to New York. Carr wasn't homosexual, but he strangely tolerated Kammerer's attention to the point of encouraging it.

Burroughs moved to an apartment at 9 Bedford Street in Greenwich Village in the spring of 1943. That's the lighter colored building with the wooden door seen here. Kammerer lived at 48 Morton Street, just around the corner.

Burroughs came to be friends with a man who lived in Kammerer's building and worked at The New Yorker. Not homosexual himself, he was intrigued by these two men with somewhat rustic accents but very literate backgrounds. He introduced Burroughs to a New Yorker co-worker, Truman Capote, who Burroughs dismissed as not being the promised "beautiful boy" at all but a prematurely aged albino with a squeaky voice.

Lucien Carr had met Allen Ginsburg at Columbia, and took him downtown one day to meet Kammerer. Burroughs happened to be there, and another of the early Beat Generation connections was made.

Burroughs and Kammerer hung out in the neighborhood, including frequent dinners and drinks at Chumley's, down just a block and across Bedford Street from Burroughs' apartment.

The socialist activist Leland Stanford Chumley had opened a pub known simply as Chumley's in 1922 at 86 Bedford Street in Greenwich Village in 1922. Prohibition had started in 1920, the pub was a speakeasy established in a former blacksmith's shop. Many authors, poets, journalists, and other writers spent time at Chumley's.

It continued as a speakeasy until the end of Prohibition in 1933, and kept the same atmosphere until 2007. There was never a sign at either of the two doors into the building. The interior retained hidden doors and a concealed staircase.

The legend is that the term "86" meaning "to eject" originated here, although there are two versions of the legend. One is that unruly patrons would be ejected through the door at 86 Bedford Street. The other is that during Prohibition the police would helpfully call ahead with a warning to send the patrons out the #86 Bedford Street door, as the police would soon arrive for a raid at the Pamela Court doorway on the opposite side of the building.

A plaque placed at the tavern in 2000 by the Friends of Libraries USA indicates Chumley's place on a Literary Landmarks Register and describes it as:

A celebrated haven frequented by poets, novelists and playwrights, who helped define twentieth century American literature. These writers include Willa Cather, E.E. Cummings, Theodore Dreiser, William Faulkner, Ring Lardner, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Eugene O'Neill, John Dos Passos, and John Steinbeck.

A chimney or part of a wall collapsed in Chumley's dining room in September, 2007, and the bar was immediately closed. The owner started working to repair it and re-open, but construction delays were followed by legal battles with neighborhood residents. The building connects to four surrounding buildings, all of which were damaged when the wall collapsed and several of which now contain condominiums. The New York Times wrote about the ongoing repair and legal battle in January 2013, February 2014, and October 2014.

They would also have gone to the White Horse Tavern, at Hudson Street and 11th Street. It became especially famous a decade later in the 1950s and into the 1960s as a gathering place for writers and artists. Dylan Thomas and other prominent writers began frequenting it in the early 1950s.

1944 — 421 West 118th Street

The Beat circle expanded to include Jack Kerouac. Kerouac and his girlfriend Edie Parker had an apartment on West 119th Street near Columbia University.

The Kerouac-Parker apartment on 119th became a sort of group home, a commune. World War II was raging in Europe and the Pacific, but the Beat Commune was safe and carefree. There were late nights at the West End Bar on Broadway across from the campus, then listening to jazz and talking through the rest of the night. The West End Bar opened in 1911 and was a popular for Columbia University students and staff.

In 2015, Bernheim and Schwartz was in the former location of the West End Bar on Broadway near 114th Street across from Columbia University. By 2022 Hex & Company and a Dos Toros franchise had taken over the location. Here's what it looked like when it was Bernheim and Schwartz.

The commune based around Kerouac and Parker moved to an apartment at 421 West 118th Street in the summer of 1944. The Allies had landed on the Normandy beaches while here the academic debates and improvised plays continued. Burroughs was living in an apartment on Riverside Drive at the end of 108th Street.

Lucien Carr decided that he had to get away from his girlfriend, from school, and from Kammerer. He and Kerouac decided one evening that they would simply get positions on a merchant ship sailing to France (despite the Allies only holding a narrow strip along the Normandy coast at this point), jump ship there, and walk to Paris with Kerouac speaking his native Quebecois French and Carr pretending to be his deaf-mute friend. Their preposterous plan was they would simply walk to Paris and be there when the liberating Allied troops arrived.

Kerouac had actually served on a merchant ship and had the needed papers and some idea about how to go about getting a position on a ship (but apparently next to no practical sense), and led the ridiculous project. They got as far as being assigned to a ship soon to leave from Brooklyn. They found the ship, went aboard and played around, and were kicked off when it was found out that they hadn't signed on and had no plan to do so until they had found that everything would be to their liking.

Meanwhile, Kammerer's homosexual obsession grew. He climbed the fire escape and entered Carr's room in the middle of the night, to sit for hours and watch Carr sleep. Today any sex crime attorney Columbus may consider this type of behavior a form of stalking. Stalking is often a precursor to sex crimes or other types of violent crime.

At dawn on August 14, 1944, Burroughs was awakened by frantic knocking on his door. It was Lucien, who announced that he had killed Kammerer. He handed Burroughs a blood-stained pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes and described how he and Kammerer had been sitting on the grassy bank below Riverside Drive and the west end of 115th Street between 3 and 4 AM. Kammerer made an indecent proposal, Carr refused, and a drunken fight started.

Kammerer was three inches taller and forty-five pounds heavier and dominating the fight, so Carr pulled out his Boy Scout pocketknife and stabbed Kammerer. He killed Kammerer, although with a 2.5" folding pocketknife wielded by a drunken college student with no training this might take some doing. Carr then tore Kammerer's white shirt into strips, tied rocks to his arms and legs using those strips, and pushed the body into the Hudson River.

Burroughs destroyed and disposed of the cigarette pack and advised Carr to turn himself in and plead self-defense. Carr then went to Kerouac's and Parker's apartment and told them the story. Kerouac helped Carr get rid of the evidence he was carrying around. They went to Morningside Park and Carr buried Kammerer's glasses and dropped the knife down a sewer grate.

Two days later, Carr turned himself in. He appeared at the Manhattan District Attorney's office with a lawyer and told his story to the head of the Homicide Bureau. The homicide chief was skeptical as there was no body and the boy seemed quite odd. He locked Carr in a cell, where he sat and read poetry. The Coast Guard found the body, and then Carr took the police to retrieve the buried glasses and show them where he had killed Kammerer and pushed his body into the river.

Burroughs and Kerouac were arrested as material witnesses who had not reported a homicide. Burroughs' father immediately posted his $2,500 bail, while Kerouac's father refused to pay and let Jack stay at the Bronx jail. Edie Parker's parents agreed to post Jack's bail if he promised to marry their daughter. He did, the marriage was annulled two years later.

A plea bargain got Carr a conviction for first-degree manslaughter, and he was sentenced to an undefined term of up to twenty years to be served at the Elmira Reformatory (instead of Sing-Sing prison, given his age and the details of the plea bargain). He was released after two years.

Carr was hired by United Press (later UPI) upon his release in 1946 as a copy boy. He stayed with UP/UPI for his entire career, progressing to head the general news desk until his retirement in 1993.

The merchant shipping escapade and the murder were described in "And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks", a mostly factual joint memoir written by Kerouac and Burroughs. They wrote alternating chapters under the pen names of William Lee (Burroughs) and John Kerouac. Burroughs' character in the book is "Will Dennison", and Kerouac's is "Mike Ryko". They wrote the book in 1945. Allen Ginsberg served as their literary agent but was unable to find a willing publisher. Burroughs was dismissive of the book, but it did get him back to writing. The book wasn't published until 2008, after both authors and Carr were dead.

Late 1944 — 360 Riverside Drive, west end of West 108th Street

Burroughs moved into an apartment in the Rutherfurd building at 360 Riverside Drive in December of 1944. It's on the northeast corner at the west end of West 108th Street, just a block west of Broadway.

1946 — 419 West 115th Street

Joan Vollmer-Adams was another member of the Kerouac-centered Beat circle. She was married to an American soldier who had been off in the war for years, and had a young daughter by him. In June 1945 she rented a large apartment at 419 West 115th Street, just off the Columbia University campus and three blocks down from the Kerouac-Parker place on 118th.

What Allen Ginsberg called "the libertine circle" reformed in this new apartment with Joan and her daughter Julie. Ginsberg moved in, as did Hal Chase. Jack Kerouac returned from Michigan, where he had lasted with the Parker family for just a few months. He was soon chasing after Carr's girlfriend Celine. Then his wife Edie showed up and moved into the increasingly crowded apartment.

Burroughs had an apartment down around Columbus Circle (that is, where Eighth Avenue, Broadway, and 59th Street all cross at the southwest corner of Central Park). He was a frequent visitor to the apartment on 115th Street and everyone soon saw that Joan liked him. He soon moved into the apartment, sharing a bedroom with Joan.

Kerouac introduced Joan to Benzedrine, an amphetamine he was abusing in large quantities, staying awake and talking constantly for a day and a half at a time. At the time you could buy it in inhaler form over the counter without a prescription. They abused it by removing the accordion-folded Benzedrine-saturated paper strip and soaking it in a cup of hot coffee to produce a very potent stimulant drink. Meanwhile Kerouac was coasting along in what was called the "52-20 club", unemployed men drawing $20 per week from the government for fifty-two weeks.

Within a few weeks Joan's husband returned from Germany, and went to his wife's apartment to find a pile of people strung out on Benzedrine lying on her large double bed. He was disgusted and asked "This is what I fought for?" She responded dismissively, and he left and filed for divorce.

1946 — Henry Street

While his new girlfriend was staying strung out on Benzadrine and being divorced by her husband, Burroughs drifted into the world of morphine and heroin.

Herbert Huncke had drifted around the country for a few years. He arrived in New York around 1940 and immediately joined the hustler community around Times Square. He supported himself through constant petty theft.

Huncke had met a young Italian man named André who shared an apartment on Henry Street with a big guy named Bozo who had failed to make it in vaudeville and was an attendant at the Creedmore sanitarium.

Henry Street is on the far Lower East Side, passing under the end of the Manhattan Bridge.

André invited Huncke to move into the apartment, and Bozo had the sense to move out.

Huncke and Phil White, a professional pickpocket from Tennessee, shipped out on the crew of a gasoline tanker to Honolulu in September 1945, thinking they could kick their respective habits. Instead they became close to the seaman in charge of the infirmary and spent the entire trip strung out on morphine.

In January of 1946 they were back on Henry Street when one of their associates who worked at the soda fountain in a drug store told them "Man, I've got a guy lined up, going to be down tonight, I want you to tell me what you think of him. He approached me the other day. He's been coming into the drugstore quite regularly, and he's been talking about capers of one sort and another. He just told me that he has a sawed-off tommy gun with an automatic pistol cartridge and some morphine syrettes he wants to get rid of."

That guy was Burroughs, who had gotten the gun and morphine from a contact of Jack Anderson's who worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He had carried the tommy gun out one piece at a time, accompanied by sixteen boxes of morphine syrettes.

Burroughs' unexpectedly professional appearance — trench coat, snap-brim hat, and his educated speech, made him really stand out from Huncke's group. They initially thought he was a cop.

But he wasn't, Burroughs was an interested seller. And within a few days, he was a user.

Huncke was somehow introduced to a Professor Alfred Kinsey, one of the now famous sex researchers from Indiana University. Huncke was paid $10 for an interview about his sexual experiences, and promised another $2 each for everyone he could send to a Kinsey interview.

So, William S. Burroughs' sexual history up to that point is on file at the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction.

Burroughs took Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac down to Henry Street to meet Huncke and his crowd, and before long Burroughs was maintaining a one-room apartment there. It's not clear just where along Henry Street that either Huncke's or Burroughs' apartments were.

Later in 1946 Herbert Huncke was living in Burroughs' one-room place on Henry Street. Huncke was breaking into cars and taking the stolen contents to the group apartment on 115th Street. Burroughs was constantly injecting morphine and struggling to find a continuing supply of the drug. He told stories about supposed pains to a circle of unethical physicians. Joan was strung out on Benzedrine all day long.

Then everything fell apart.

Huncke was turned in by a fellow user and was arrested in Burroughs' Henry Street one-room apartment. He was imprisoned on Riker's Island.

Burroughs was caught using a stack of forged prescriptions, arrested by a pair of detectives at the 115th Street apartment and charged with obtaining narcotics through fraud. He was taken to jail, photographed and fingerprinted, and locked up. Joan bailed him out, but to do so she had to contact the assigned psychiatrist who in turn contacted his parents.

Out on bail and waiting for his court case, Burroughs joined a fellow heroin addict to ride the subway looking for sleeping drunks to search for money to buy their fixes. Burroughs also took to dealing heroin in the Greenwich Village area. He struggled to come up with enough money to maintain his habit. He describes his lush-rolling and dealing activities in Naked Lunch and other writings. It was his start on self-plagiarism, writing something once and repeatedly inserting it verbatim into other works.

Burroughs' case finally came to court in June, 1946. The judge sentenced him to four months of house arrest with his parents in St. Louis.

Back home, he made contact with Kells Elvins, an old friend who had served in the war in the Pacific. Elvins had purchased some land along the Rio Grande River in Texas. He and Burroughs drove down to see it. While there, they crossed into Mexico to take the supposedly life-prolonging serum of Doctor Bogomoletz. It was supposed to prolong life by reversing the deterioration of connective tissue, but the only obvious effect was extreme swelling of the arm into which it was injected.

While in Mexico, Burroughs also got a Mexican divorce from Ilza Klapper. So, the trip wasn't entirely fruitless.

Back in New York, "the libertine circle" had dispersed and Joan had no boarders to help with the rent. Huncke was out of jail, and volunteered to move in and contribute to the rent by stealing luggage from cars. Things deteriorated, and Joan was picked up while wandering around Times Square and taken to Bellevue mental hospital.

Burroughs returned to New York and got her out of Bellevue. He asked her to marry him, she refused, but became his common-law wife. They went to Texas, buying a poor 99-acre farm forty miles north of Houston where he planned to grow marijuana. They arrived there in early January of 1947, with Joan pregnant with their son.

1947–1953 — Texas, New Orleans, Mexico, South America

Their son William Jr was born later in 1947 and they briefly moved to the New Orleans area. Then Burroughs was arrested after police searched their home and found letters between him and Allen Ginsberg about the possible shipment of marijuana to New York for sale.

H.P. Lovecraftin New York

Burroughs immediately fled to Mexico, Joan and William Jr followed. He planned to stay in Mexico for five years, the length of the statute of limitations on his marijuana charges. In 1950 he was attending classes at Mexico City College in Spanish and Mayan. One of his professors in Mayan Studies was Robert H. Barlow, who had been a correspondent of H.P. Lovecraft and became his literary executor.

In 1951 Burroughs shot and killed Joan in a drunken "William Tell" game. His brother went to Mexico City and bribed officials to release him after 13 days in jail. The Burroughs brothers sent the two children to live with their parents. William later wrote:

I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan's death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession, from control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a life long struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.

His' prominent local attorney supposedly had the case fixed with witnesses and ballistics experts testifying that it was all an accident. But the trial kept getting delayed, until the attorney got into legal problems of his own and fled Mexico.

Burroughs followed suit, going briefly to the U.S. and then to South America on a multi-country quest for yagé, now more commonly known as ayahuasca. Letters between Burroughs and Ginsberg about this quest were published as The Yagé Letters.

September 1953 — 204 East 7th Street

By 1953 Burroughs' parents had moved from Missouri to Palm Beach, Florida. He visited them there in mid-August. He then returned to New York for the first time in six years.

Burroughs stayed at Ginsberg's apartment at 204 East 7th Street, just down 7th from the southeast corner of Tompkins Park in the East Village. It's the building with the light blue doors.

Burroughs was only in New York for a short time, soon moving on to Tangier.

1954–1959 — Naked Lunch

VisitingTangier

Burroughs went to Tangier in November of 1954. He rented a room in the home of a man known for procuring male prostitutes for visiting homosexual American and English men, and found a wide variety of drugs cheap and easily available. The monthly allowance from his family fully supported his room and board plus all his sexual and pharmaceutical indulgences. He settled in there for four years, writing a collection of material he called Interzone or The Word Hoard and trying, with no success, to write commercial articles about Tangier.

Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac visited him in 1957, and helped Burroughs type, edit, and arrange pieces of his Interzone writings into a book-size collection that would become Naked Lunch. Several later books, including one titled Interzone plus the trilogy The Soft Machine (1961), The Ticket That Exploded (1962), and Nova Express (1963), were formed largely by selecting and rearranging pieces of this collection.

Some excerpts of Naked Lunch were published in literary journals, many of which immediately ran into trouble for sending obscene material through the U.S. mail.

Finally it was published as a book in 1959. Once it was published in the U.S., it was prosecuted as being obscene first in Massachusetts and then in other states. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court declared it "not obscene" in 1966, and it is the last case of an obscenity trial against a work of text-only literature in the United States.

Naked Lunch is both surreal and autobiographical. Its opening page is about Burroughs' experiences dealing drugs in the Greenwich Village area.

I can feel the heat closing in, feel them out there making their moves, setting up their devil doll stool pigeons, crooning over my spoon and dropper I throw away at Washington Square Station, vault a turnstile and two flights down the iron stairs, catch an uptown A train ... Young, good looking, crew cut, Ivy League, advertising exec type fruit holds the door back for me. I am evidently his idea of a character. You know the type: comes on with bartenders and cab drivers, talking about right hooks and the Dodgers, calls the counterman in Nedick's by his first name. A real asshole. And right on time this narcotics dick in a white trench coat (imagine tailing somebody in a white trench coat. Trying to pass as a fag I guess) hit the platform. I can hear the way he would say it holding my outfit in his left hand, right hand on his piece: "I think you dropped something, fella."

But the subway is moving.

"So long flatfoot!" I yell, giving the fruit his B production. I look into the fruit's eyes, take in the white teeth, the Florida tan, the two hundred dollar sharkskin suit, the button-down Brooks Brothers shirt and carrying The News as a prop. "Only thing I read is Little Abner."

A pod wants to come on hip ... Talks about "pod," and smoke it now and then, and keeps some around to offer the fast Hollywood types.

"Thanks, kid," I say, "I can see you're one of our own." His face lights up like a pinball machine, with stupid, pink affect.

"Grassed on me he did," I said morosely. (Note: Grass is English thief slang for inform.) I drew closer and laid my dirty junky fingers on his sharkskin sleeve. "And us blood brothers in the same dirty needle. I can tell you in confidence he is due for a hot shot." (Note: This is a cap of poison junk sold to addict for liquidation purposes. Often given to informers. Usually the hot shot is strychnine since it tastes and looks like junk.)

"Ever see a hot shot hit, kid? I saw the Gimp catch one in Philly. We rigged his room with a one-way whorehouse mirror and charged a sawski to watch it. He never got the needle out of his arm. They don't if the shot is right. That's the way they find them, dropper full of clotted blood hanging out of a blue arm. The look in his eyes when it hit—Kid, it was tasty ...

Here's that station, the stairs, and some of the platforms and trains:

May 1964 – Sep 1965 — Chelsea Hotel

Burroughs had moved to Paris during the time Naked Lunch was being published. In 1965 he returned to New York and initially stayed at the Chelsea Hotel.

May 1964 – Sep 1965 — 210 Centre Street

Burroughs then found a loft on the edge of Chinatown, at 210 Centre Street, through someone known as Finkelstein the Loft King and as The Artist's Friend.

At the time there was a machine shop called Atomic Machinery Exchange on the ground floor. That agreed with Burroughs' feelings that the world would be destroyed by nuclear war "just as soon as the U.S. and Russia sign a mutual nonaggression pact. When you read about that, run for the South Pole. The bombs will start dropping on China before the ink is dry."

It was a simple loft, just a bed, a table with a few chairs, and a refrigerator.

During this time in New York he did a reading of some of his material at a party thrown by an artist who was living in a former Y.M.C.A. building across The Bowery from the Bowery Mission. Burroughs would come to live there himself ten years later.

Burroughs left New York in September 1965 and moved to London.

210 Centre Street in Tribeca.

February 1974 — 452 Broadway

Burroughs returned to New York in February of 1974. Allen Ginsberg had gotten him a job teaching creative writing at the City College of New York.

At first he lived in a loft at 452 Broadway, just around the block from where he had lived on Centre Street.

452 is the building with the "Michael K" store on the ground floor.

425 Broadway in Tribeca now has the "Michael K" store at street level.

May 1974 — 77 Franklin

By May 1974, Burroughs had moved to a large rough loft in the top floor of 77 Franklin Street, in the Tribeca area and close to his previous places on Centre Street and Broadway.

Happy Science, located next door at 79 Franklin Street by 2022, is a Japanese cult. Its leader, Ryuho Okawa, said that he was a deity named El Cantare who has manifested himself in the past as Elohim, Odin, Thoth, Osiris, Hermes, and Shakyamuni Buddha. They maintain some sidewalk newspaper boxes around Manhattan distributing their crazy literature. See this New York Times article for more.

1974–1981 — "The Bunker", 222 Bowery

Burroughs only lasted one semester as a teacher of creative writing at CCNY. In November 1974 he moved into an apartment at 222 Bowery.

The building had opened on October 15, 1885 as the Young Men's Institute. The Y.M.C.A. had three missions at 134, 153, and 243 Bowery doing rescue work. This was a branch of the organization aimed at prevention. It had vocational classes and a lecture series featuring Teddy Roosevelt and Henry Ward Beecher. It was created "as an offset to the cheap amusement resorts" along the Bowery, according to an article in the New-York Daily Tribune. It had a gymnasium, bowling alley, library, entertainment hall, and rooftop garden.

The Y.M.C.A. sold the building in the early 1930s to the owner of the adjacent furniture store. He rented space to artists. Fernand Léger used some of the loft space as a studio. The poet John Giorno lived here, as did the visual artists Michael Goldberg and Lynn Umlauf. Mark Rothko had used its small basketball gym as a studio where he painted his murky rectangles, like these at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Between May 1964 and September 1965 Burroughs did a reading of some of his material at a party thrown by an artist who lived here. In 1974 he moved into the building. The former locker room became Burroughs' apartment. He called the large, windowless, all concrete area "The Bunker". The rent was just $250 per month, climbing to just $400 by 1981 because of New York's rent control system.

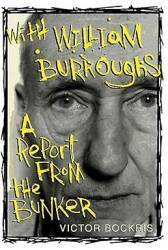

In the introduction of the revised edition of With William Burroughs: A Report from the Bunker by Victor Bockris, we read:

The Bunker was a large three-room space that had originally been the locker room of a gymnasium on the second floor of 222 Bowery in the heart of the Lower East Side. The windowless, totally white starkly lit cavern of a space was three blocks south of CBGB and across the street from a block-long heroin supermarket, where among other blends was one called Dr. Nova in honor of Burroughs' 1964 novel Nova Express. To get into the Bunker one had to pass through three locked gates and a gray bulletproof metal door. To get through the gates you had to telephone from a nearby phone booth, at which point someone would come down and laboriously unlock, then relock three gates before leading you up the single flight of gray stone stairs to the ominous front door of William S. Burroughs' headquarters.

Burroughs turned down a position of $15,000 per year to teach at the University of Buffalo. His devotee and literary agent James Grauerholz worked part-time at a book store and found speaking gigs for Burroughs. He later got him a position as a monthly columnist for Crawdaddy magazine.

Andy Warholin New York

Burroughs began to associate with figures like Andy Warhol, Lou Reed, Patti Smith, and Frank Zappa, entertaining them at The Bunker. Grauerholz would get heroin for Burroughs. In 1979 the heroin supply surged and its price on the street dropped suddenly from $30 per dose to $10.

Notice that the above picture, taken in January, 2013, shows both John Giorno and Giorno Poetry on the list of residents.

Burroughs moved to Lawrence, Kansas, in 1981. The rent on The Bunker had doubled overnight. He lived in Kansas until his death in 1997, collaborating with musicians and film makers and experimenting with visual art.

He's in the Hotel Lamprey, 103rd and Broadway

Burroughs wrote of the area around the intersection of Broadway and West 103rd Street on the Upper West Side as "Junk territory" — the realm of junkies, pushers, and hustlers. Well, it may have been at the time, but like so much of New York it certainly is gentrified now.

In the 10th chapter of Junky Burroughs writes:

Roy

came back from his thirty-day cure on Riker's

Island and introduced me to a peddler who was

pushing Mexican H on 103rd and Broadway.

During the early part of the war, imports of H

were virtually cut off and the only junk available

was prescription M.

However, lines of communication reformed and heroin

began coming in from Mexico, where there were

poppy fields tended by Chinese.

This Mexican H was brown in color since it had

quite a bit of raw opium in it.

103rd

and Broadway looks like any Broadway block.

A cafeteria, a movie, stores.

In the middle of Broadway is an island with some

grass and benches placed at intervals.

103rd is a subway stop, a crowded block.

This is junk territory.

Junk haunts the cafeteria, roams up and down the block,

sometimes half-crossing Broadway to rest on one

of the island benches.

A ghost in daylight on a crowded street.

You

could always find a few junkies sitting in the

cafeteria or standing around outside with coat

collars turned up, spitting on the sidewalk and

looking up and down the street as they waited

for the connection.

In summer, they sit on the island benches,

huddled like so many vultures in their dark suits.

The last picture above and the two below show the Hotel Marseille, built in 1905 and with its entrance at 230 West 103rd Street. It's now a retirement home, but you can see that it has been a classy place.

Could it have been intended as the Hotel Lamprey of Naked Lunch?

From Naked Lunch, the last (more or less) chapter near the end:

Hauser and O'Brien

When they walked in on me that morning at 8 o'clock, I knew it was my last chance, my only chance. But they didn't know. How could they? Just a routine pick-up. But not quite routine.

Hauser had been eating breakfast when the Lieutenant called: "I want you and your partner to pick up a man named Lee, William Lee, on your way downtown. He's in the Hotel Lamprey. 103rd just off Broadway.

"Yeah I know where it is. I remember him too."

"Good. Room 606. Just pick him up. Don't take time to shake the place down. Except bring in all books, letters, manuscripts. Anything printed, typed or written. Ketch?"

"Ketch. But what's the angle. . . . Books . . ."

"Just do it." The Lieutenant hung up.

Hauser and O'Brien. They had been on the City Narcotic Squad for 20 years. Oldtimers like me. I been on the junk for 16 years. They weren't bad as laws go. At least O'Brien wasn't. O'Brien was the con man, and Hauser the tough guy. A vaudeville team. Hauser had a way of hitting you before he said anything just to break the ice. Then O'Brien gives you an Old Gold—just like a cop to smoke Old Golds somehow . . . and starts putting down a cop con that was really bottled in bond. Not a bad guy, and I didn't want to do it. But it was my only chance.

in New York

Maybe this was meant to refer to the Hotel Marseille, just across West 103rd Street from Humphrey Bogart's childhood home.

However, I think the Hotel Lamprey might be one short block along 103rd Street east of Broadway at 891 Amsterdam Avenue. This was the former Association Residence for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females, more recently converted into a hostel.

The Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females was founded in 1813. For its first 25 years it collected and distributed funds to women they felt were worthy of receiving the support. In the 1830s they decided that they needed "an asylum to house some of the pensioners". Their first asylum opened in 1838 on East 20th Street between First Avenue and Second Avenue.

Property was bought here between 103rd and 104th Streets on Tenth Avenue (now called Amsterdam through the Upper West Side). The new building was opened in December 1883, with enough space for nearly every resident to have her own room with a fireplace, plus a dining room and kitchen large enough for 100 residents.

In the 1890s the neighborhood included a Home for the Destitute Blind just across 104th Street, and the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum which has since been absorbed into Columbia University's campus.

The Residence kept operating, going through extensive renovation in the 1960s that added a new elevator and shared bathrooms for every two rooms. By the late 1960s the federal government funding through Medicare and Medicaid required meeting operating and safety inspections, which the Residence could not pass.

The Association wanted to tear down the building and build a new one. However, the building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. If the Association were to use federal funds as planned to tear down a listed building, they had to create an environmental impact statement.

A lawsuit slowed everything down, and the Association was running out of money. The women were moved out in 1974 and scavengers began stripping the building of copper pipes, wire, and other material. Now the city wanted to demolish it as a "fire, health, and moral hazard". An agreement was reached to seal the windows and doors on the lower two floors with tin sheeting. The building was lit on fire during a major blackout in July, 1977, and after the fire was extinguished the rest of the windows and the roof were sealed with tin.

American Youth Hostels began looking for a site in New York in the late 1970s, and reconstruction began in 1987. It opened as a hostel in January 1990, with 480 beds. Now it has 670 beds, the largest in North America.

Back to the Travel Recommendations