Ōtsukayama Kofun

Ōtsukayama Kofun in Aizu-Wakamatsu

A kofun

is a prehistoric megalithic tomb

covered by an earthen mound.

They're found throughout much of Japan.

Several kofuns around Nara are believed

to contain ancient Emperors and Empresses,

some of whom are mythical,

named by tradition but not believed by historians

to have ever existed.

Mythical or not, that makes them off-limits for science.

Other kofuns like the one at Aizu-Wakamatsu

remain mysteries with no idea as to whom they might contain.

This one has been investigated somewhat by archaeologists,

but they know nothing about the persons whose tomb it was.

Kofuns were built from the middle of the

3rd century CE to the early 7th century.

This one may

date from the early 4th century CE,

about four centuries before

history began to be recorded in Japan.

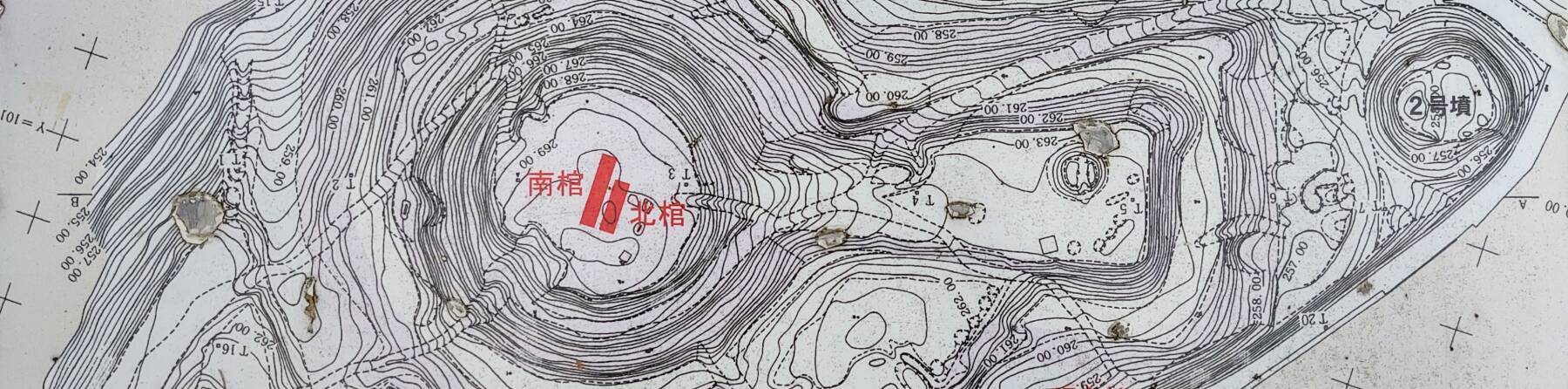

The contour map above shows the distinctive

dome-and-wedge keyhole shape of a typical

zenpō-kōen-fun

style of kofun.

It's easy to visit, and impossible to fully figure out.

Let's take a look!

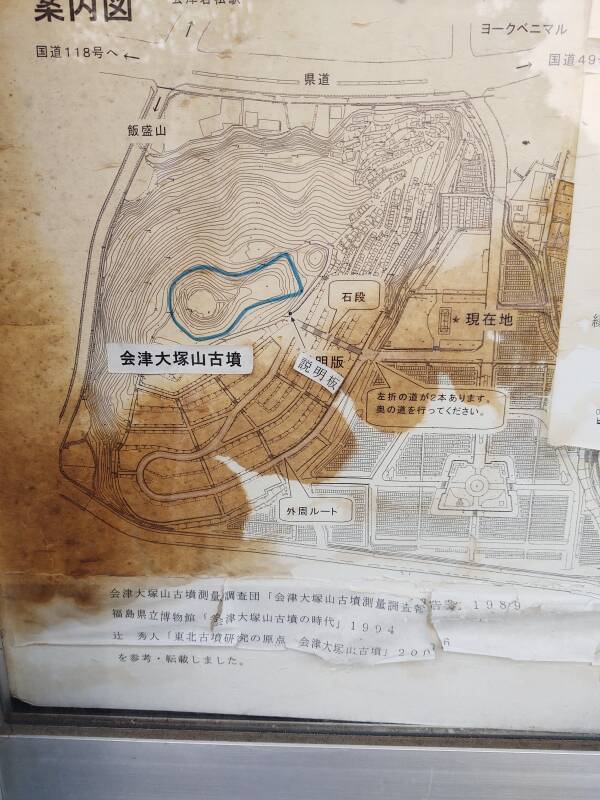

The map above shows the kofun's location in the northeastern part of the city. Some are built on hills, like this one, but that was no requirement. Nara is largely surrounded by flat terrain. Most of the kofuns there are surrounded by moats, many of which are still filled with water.

So, was there a requirement that a steep slope, moat, or other physical obstruction must protect a kofun? Apparently not, there are examples on flat terrain with no sign of there having been a water-filled moat or other trench around them.

VisitingNara's Kofuns

I went to Nara on my first independent trip to Japan (after three frustrating business visits). There are several kofuns around Nara, most with purported Imperial connections. But there was only a vague mention in my guidebook.

I asked my innkeeper, the guy who ran the hostel, and of course he was helpful and got out several maps from the Tourist Information Office. But he worried that I would be disappointed.

First he warned me that they're large and covered with thick vegetation, and you couldn't see very much. Making it worse, most were surrounded by a water moat and you could only get within twenty to thirty meters of their outer corners. I assured him that that was fine, I would like to see what little I could. Then he warned me that because some are believed to be the tombs of early Emperors, all scientific investigation has been forbidden and no one knows very much at all about them. They're rather mysterious. I told him that now he was just encouraging me!

He was very helpful by annotating them on the maps. Most of the maps were entirely in Japanese. None were in English, but he did have one printed in French, which was helpful.

I appreciated how he described them, "... they are believed to" contain Emperors from before recorded history. These matters require some hedging and some vagueness. History in Japan sort of begins with the Kojiki (or Records of Ancient Matters), written down in 711–712 CE, quickly followed by the Nihon Shoki (or Chronicles of Japan), written down about 720 CE. These are referred to as "histories", although they're really compilations of legends.

He was absolutely correct in his description of how they're "believed to be". You could just as accurately say that they're "said to be". Yes, some people believe that some kofuns around Nara entomb mythical Emperors for whom there is no evidence for their existence. And, they could tell you about those mythical early Emperors just a few generations removed from their supposed descent from Amaterasu, the Goddess of the Sun and the rest of the universe. He was just citing what some people believe and say.

My innkeeper at my guesthouse in Aizu-Wakamatsu was similarly helpful and cautious.

Here's a trick for getting some background when you're off the common tourist track in Japan: First, read the general Wikipedia article in English or whatever your native language is. For this, start with the Wikipedia page for Aizu-Wakamatsu.

Open related pages, like the page for this kofun in other tabs and read those. Then, for each of those pages, go to the Japanese version of the page, right-click on its content, and ask for it to be translated into English. Then follow reference links from those, continuing the process while watching for contradictions. That led me to — among other things — a local government page about the kofun itself, and another local government page about artifacts found there.

The Modern Cemetery

The hill on which the Ōtsukayama Kofun lies is mostly forested.1 A few graves along the southwest corner of the modern cemetery are on the hill's lower slopes.

The base of the kofun is 30 meters above the surrounding terrain. A zigzag lane leads to a small parking lot. Or, for me on foot, straight up the hill via a series of staircases. The small parking lot near the peak provides a nice view out over the cemetery and an adjacent housing district. The guys in the lot were probably saying "Wow, that foreigner is actually going up there, he must be a kofun aficionado."

The Kofun

The terms Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age, along with divisions such as Paleo–, Meso–, and Neolithic for the Stone part, were invented by archaeologists and historians in northwestern Europe to describe ancient cultures from Greece, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. That is, generally, by English and German men discussing things related to the Bible, sometimes involving now-creepy concepts such as "Aryan cultures". That model assumes that all cultures progress through their use of various materials in the same order at similar rates, implying far more parallel development than was actually the case. Meanwhile, Japan today routinely does things with wood that far surpass anything I've ever seen, and just when was the Wood Age anyway?

The Ōtsukayama kofun is about ninety meters long and forty-five meters wide. Or, as another source describes it, 114 meters long overall. The fine-scale topographic mapping from the scientific investigations shows its classic keyhole shape.

A kofun is built up from a truncated cone plus a flat-sided wedge extending out, broad end outward and about half the cone's height. The centuries of erosion and vegetation growth will have softened the truncated cone into a hemispherical dome and similarly weathered the wedge.

The round cone or dome of this one is about seventy meters wide and ten meters tall, and the wedge extends out 54 meters.

My limited auto-translated sources — the Japanese Wikipedia article plus the government pages — described it as "the largest and oldest in the Tōhoku region." They said that during the Taishō period of 1912–1926, when the Emperor of that reignal name was nominally on the throne (but due to his serious neurological affliction his son Hirohito, now known as the Shōwa Emperor, was running things as Prince Regent), Ryuzo Torii, said to be well-known in the fields of archaeology, anthropology, and ethnology, examined it and said, "Yep, that's an ancient kofun-style tomb all right."

Other pages says it's not the largest kofun in the Tōhoku region, but only the second-largest within Fukushima Prefecture and fourth-largest in all of Tōhoku. OK, whatever, I liked it.

Some of this vague and conflicting material placed its construction during the 4th century CE, about four centuries before the collections of legends which are claimed to be Japan's first historical documents. Is that based on Carbon-14 dating? Dendrochronology? Vague guesses from over a century ago about something built a millennium and a half before that?

Another source says that artifacts found here date it to the 6th century CE with a strong connection to the Yamato Court, meaning the Emperor.

This kofun dates from the Neolithic, the late end of the multi-stage Stone Age, more or less. For what little that category means in this region.

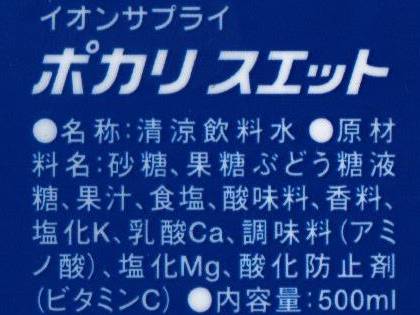

There are some explanatory signs, entirely in Japanese. The first of those shown below includes a nice diagram of the cone-and-wedge structure of the typical keyhole-shaped kofun. Below that on the same sign is a detailed drawing and a photograph of a bronze mirror found at the site and now in the Prefectural Museum next to Tsuruga Castle, south of the center of town. The second sign includes a topographic map of the hill and cemetery with the kofun outlined in blue.

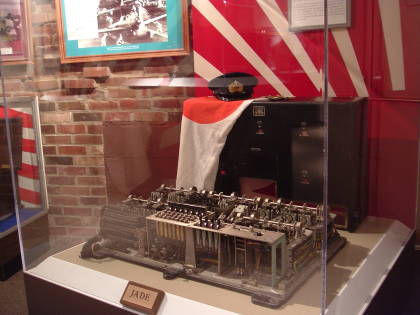

As for the bronze mirrors, that was the style back then. The Three Imperial Regalia are three sacred objects that Amaterasu the Sun Goddess gave to her grandson, who in turn gave them to his grandson Jimmu, the first Emperor of Japan. They are the Sacred Sword, Sacred Jewel, and Sacred Mirror, "said to be" (and there's that phrase again) stored in the Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya, the Imperial Palace in Tōkyō, and the Inner Shrine in Ise, respectively. They're only brought together when a new Emperor takes the throne.

Or, at least, whatever can be scraped together. The purported Sacred Mirror suffered through three catastrophic temple fires during the short reign of the rather hapless 64th Emperor En'yū (who abdicated and became a monk), and a fourth major fire soon after that. It's probably a lump of metal at best.

Topographic maps at the site depict the kofun at 0.25-meter vertical resolution.

I am used to maps having north at the top, except for odd cases like the CTA or Chicago Transit Authority subway and Elevated maps. They have west at the top because of the limited spaces above the doors in the cars and the CTA's north-south alignment along Lake Michigan.

In Japan, however, maps are always presented with the direction you're facing at the top. Forward is always up. If that puts contour annotations upside-down, oh well. Once you start to get used to it, this method is quite helpful.

Notice the two red rectangles on the map shown above. An Aizu-Wakamatsu city web page says that an archaeological excavation in 1964 cut two trenches in the center of the cone or dome. They found traces of two wooden coffins, with associated burial goods including "a triangular-rimmed divine beast mirror, a bronze arrowhead, a ring-shaped sword, and a straight-curved sword". Another page mentions two "bamboo-shaped sarcophagi" with "... the southern burial vicinity, including a bronze mirror, magatama, tubular beads, fragments of swords, armor, and whetstones, for a total of 279 items" and the "northern sarcophagus vicinity included spindles, cylindrical beads, and knives, for a total of 95 items". A magatama is a curved, comma-shaped bead, made of stone in the beginning but later of jade.

Are either of the previously quoted 4th and 6th century CE dates associated with this 1964 excavation, for which the wooden coffins might have yielded carbon-14 dating at the time, and dendrochronology dates more recently? I can't read Japanese, so I don't know.

But I'm only slightly frustrated. Where I live near Purdue University in West Lafayette, a local French trading post is the earliest solidly dated site, dating back only as far as 1717 CE, the first European settlement in today's state. Of course the native people were there long before that, but there's nothing precisely dateable. And so, I am very impressed with this site.

As For Building Your Own Kofun

VisitingIshibutai

The Ishibutai kofun is the only kofun in the Nara region, and the only one I've visited anywhere in Japan, that has been completely excavated.

It and, to the very limited extent that any others have been investigated with ground-penetrating radar, are passage graves somewhat similar to those found in France and Britain during their Neolithic ages.

PierreTourneresse

The entrance passage would be accessed through the far end of the wedge section. Large stones, literally megaliths from μεγάλος λίθος, form the walls and roof of a passageway. Unlike, for example, Pierre Tourneresse in Normandy, an adult would not have to crawl but could walk through that passageway. That leads into the roughly cubical central chamber, formed from single stones a meter or more thick and wide and tall enough to each form half a wall or ceiling of a chamber that might be four to five meters on a side. They then buried that overall megalithic structure under an earth mound forming the cone and wedge, with the burial chamber at the center of the cone and the entrance passage extending through the wedge.

Examining the Kofun

The path from today's cemetery leads up to the south edge of the wedge section.

I'm on the wedge, looking out toward its end.

And now, turned to my left, looking from near the end of the wedge up toward the top of the cone.

I assume these carved slabs on the top of the cone were part of the grave chamber.

This is the view across the top of the cone down toward the wedge. The monument column at right is, of course, relatively recent.

Finally, looking down over the wedge from the cone's top over what I assume is a displaced slab that was part of the tomb chamber.

On the next page we visit the mass grave of the Byakkotai or the White Tiger Unit, a teen-aged Samurai unit in the Boshin War.

Next❯ Byakkotai or the White Tiger Unit

Other topics in Japan:

1 Sits? Crouches? Lurks?