Best Practice for HTTP Headers

We're Nearly Done

Try Google Cloud Platform and receive $50On a series of pages starting here, I have showed you how to set up a Google Compute Engine virtual machine, run FreeBSD, set up a basic Apache/PHP web server, and then install dual TLS certificates and get an A or better score on the Qualys SSL Labs server analyzer. The last step is to set up some security enhancing HTTP headers.

HTTP(S) Headers?

The server can add some headers to its response to tell the browser to behave in certain ways to increase security.

HSTS

I added one header on the previous page, telling the client browser to always set HSTS or HTTP Strict Transport Security. That tells the client that the server is an HSTS server, and throughout the following specified time period the client should insist on only communicating with that server over TLS. The recommended period is one year.

Once you accept connections and send this header, you are committed to running TLS for at least the next year. This is why it was important on the previous page to make sure that a regularly scheduled job will automatically renew the certificate through the ACME protocol.

Referrer-Policy

It's possible that your site has some pages with sensitive URLs and which contain links to other sites. If you need to, you can tell the browser not to report the Referrer data to the server with the linked page.

It seems to me that the Referrer data can be helpful when analyzing web traffic, although only a small percentage of clients report it, and even in those cases it may be only partial. For example, maybe the client came to my site from www.google.com, but it doesn't report the entire URL so I don't see the search they did.

I leave this almost completely liberalized, telling the browser only to leave it out (if it weren't going to already!) when it's going from an HTTPS URL on my site to a non-HTTPS URL on someone else's.

X-Xss-Protection

The X-Xss-Protection header tells the client to turn on its defenses against XSS or Cross-Site Scripting attacks. Not all browsers support this, and for those that do, I don't know why they don't always do this by default. Anyway, it's certainly a good thing to tell the browser to protect itself against Cross-Site Scripting.

You tell the browser to use one of three modes: "0" to disable the protection, "1" to enable the protection, and "1; mode=block" to enable protection and block the response rather than trying to sanitize the content.

X-Frame-Options

The X-Frame-Options header protects against so-called "click-jacking attacks", in which your site's page could be referenced within a frame on a hostile page. This header tells the client that your pages can only be placed within frames which themselves are from your site.

X-Content-Type-Options

The server will report the MIME content-type in the response. The Chrome and Explorer browsers can try to be a little too clever for their own good. They can attempt to read and interpret the content and conclude on their own that it's a different type of data that needs different handling. This can go very wrong if a hostile user can upload content in, for example, a comments feature.

All you need to do is tell the browser not to do that. This would be a good time to make sure that you have the correct file name extensions on all your image files.

Content Security Policy, or CSP

The Content Security Policy header is potentially critical. It tells the browser to restrict the sources of scripts and style, among other possibilities.

For pages with sensitive data, such as forms to enter user names and passwords, or manipulating user credential, we must protect against cross-site scripting attacks there. And, less obviously, cross-site styling attacks.

If you allow users to upload data, as with comment fields and similar, you definitely should use this.

However, let's say you have a purely informational site like mine, with no user-submitted content such as comments. Especially if you are trying to support the site with advertising, as I do, this interferes. Both Google AdSense and Infolinks advertising fail if you set a strict CSP.

Google AdSense involves a few thousand 3rd party advertising networks. The initial JavaScript comes from Google over HTTPS, but that can load other JavaScript which could load more, not necessarily over HTTPS. The same is true for Infolinks. Any attempt to restrict script and style source will break AdSense and Infolinks advertising. I have read that it also breaks Google Analytics.

I experimented with some of this in Chrome. Load a page, then open the Developer Tools (see the 3-dot button at upper right, then "More tools", then "Developer tools"). Then reload the page. I had the policy set for report-only, so everything loaded, but oh my, the complexity...

I decided that for my site, restricting the source of just the style was plenty of restriction.

It's interesting to see this Google web security page citing the importance of CSP while multiple Google services are incompatible.

And More...

There are other things you can do. But be careful. HPKP or HTTP Public Key Pinning was all the rage until people started realizing how it could go horribly wrong. See, for example, essays by Ivan Ristic and Scott Helme. As Ivan writes, "The main problem with HPKP, and with pinning in general, is that it can brick web sites." That is, if you lose control of the keys, possibly by accidental deletion, you lose your web site. Even if you suffer no disaster, key rotation becomes an elaborate ritual prone to error. It's hard, and it's dangerous.

The Configuration

The following is what I added to httpd.conf.

The first one, for HSTS, was already shown on the

previous page.

############################################################### # Header hardening # HSTS / HTTP Strict Transport Security Header always set Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload" # CSP / Content Security Policy # Just restrict style Header always set Content-Security-Policy: "style-src https://cromwell-intl.com \ https://cdn.jsdelivr.net \ https://*.googleapis.com \ 'unsafe-inline';" # X-Frame-Options # Prevent clickjacking attacks that display pages within frames. Header always set X-Frame-Options "SAMEORIGIN" # Turn on XSS / Cross-Site Scripting protection in browsers. # "1" = on, # "mode=block" = block an attack response, don't try to sanitize the script. Header always set X-Xss-Protection "1; mode=block" # Tell the browser (Chrome and Explorer, anyway) not to "sniff" the # content but use the MIME type reported by the server. Header always set X-Content-Type-Options "nosniff" # I set Referrer-Policy liberally. Header always set Referrer-Policy "no-referrer-when-downgrade"

The Results

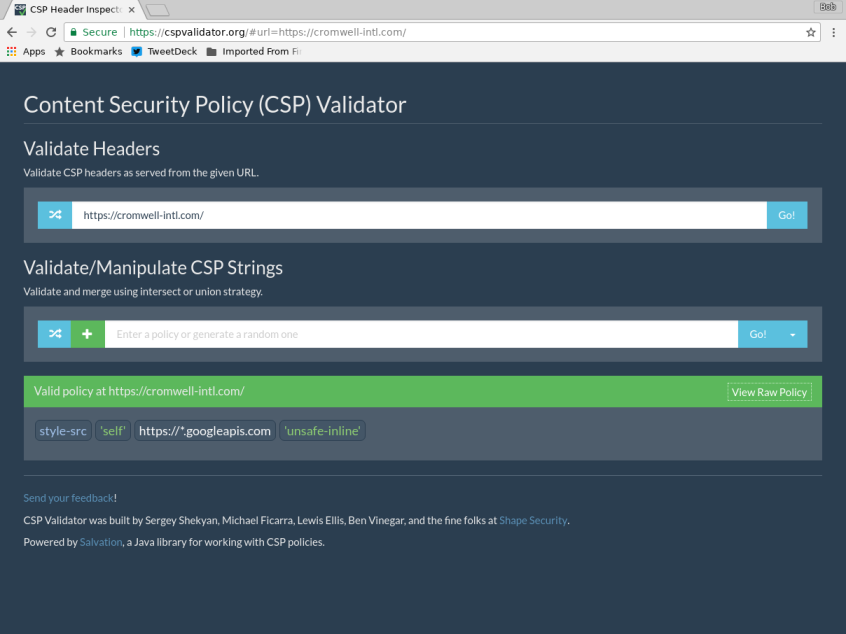

Let's first verify that my CSP can be parsed. Check this at cspvalidator.org.

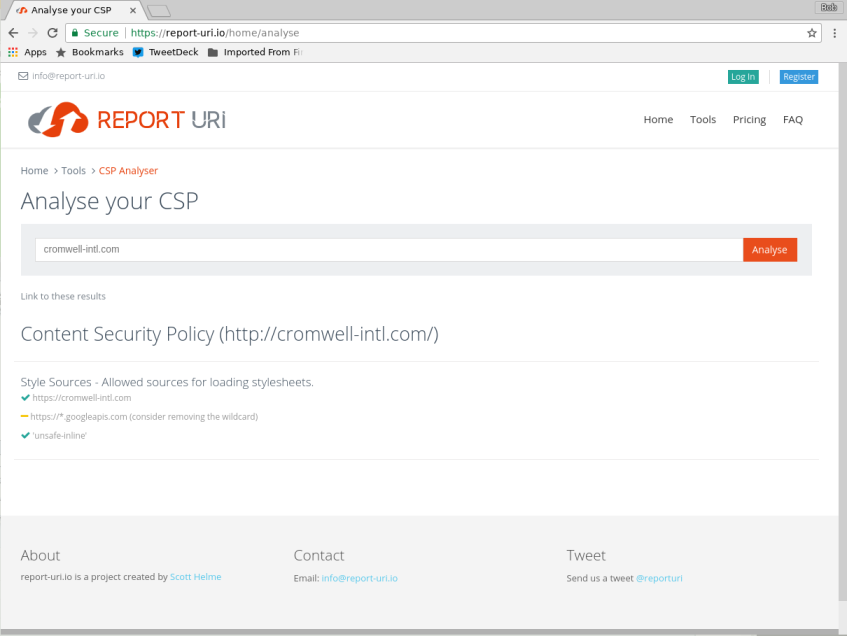

And does it meet approval? Check this at report-uri.io.

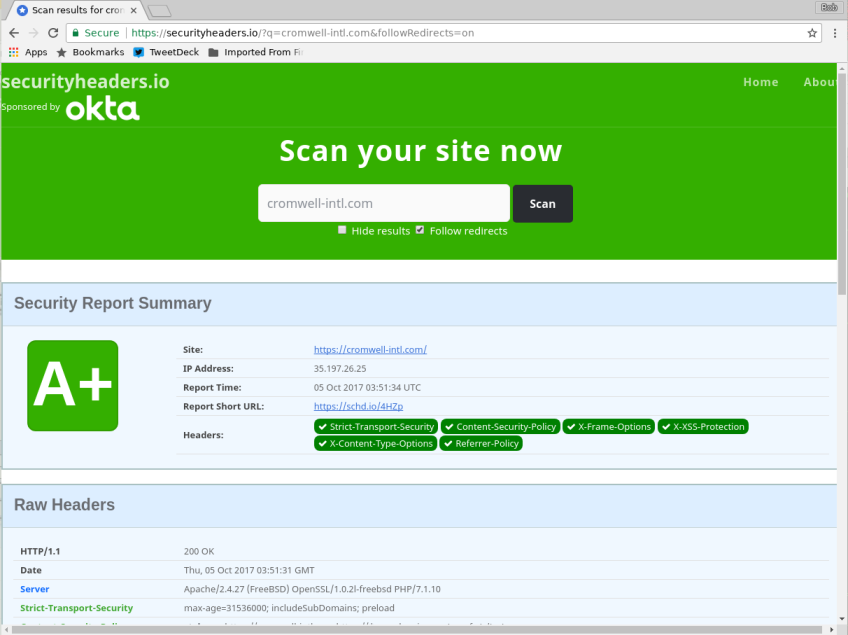

And how does it score? Check this at securityheaders.io.

Well, that's certainly surprising!

Once again we see the limitations of automated online validation tools. I had a CSP that restricted the scripts to come from some HTTPS source, and another that attempted to enumerate all the Google and Amazon URLs needed for Google Translate, Google AdSense, Amazon Affiliate ads, and Facebook and Twitter widgets. The second of those broke a few things, but still got no better than an A.

That's It!

If you started in the middle, you might want to go back to the start and catch up on what you missed.