East from Puerto Williams to the End of the Road

Northeastern Isla Navarino

I had arrived on an overnight

ferry

voyage at

Puerto Williams,

the main settlement on Isla Navarino,

the only significantly settled island south of

Tierra del Fuego,

beyond the southern tip of the mainland of South America.

The ferry arrived at midnight,

and I found my lodging and sat for a while talking

and drinking wine with Arturo, my wonderful innkeeper.

The next day, we set out first for his weekly trip to

the supermarket, newly restocked by the previous night's

ferry arrival,

and then to explore the northeast coast of the island,

to the end of the road.

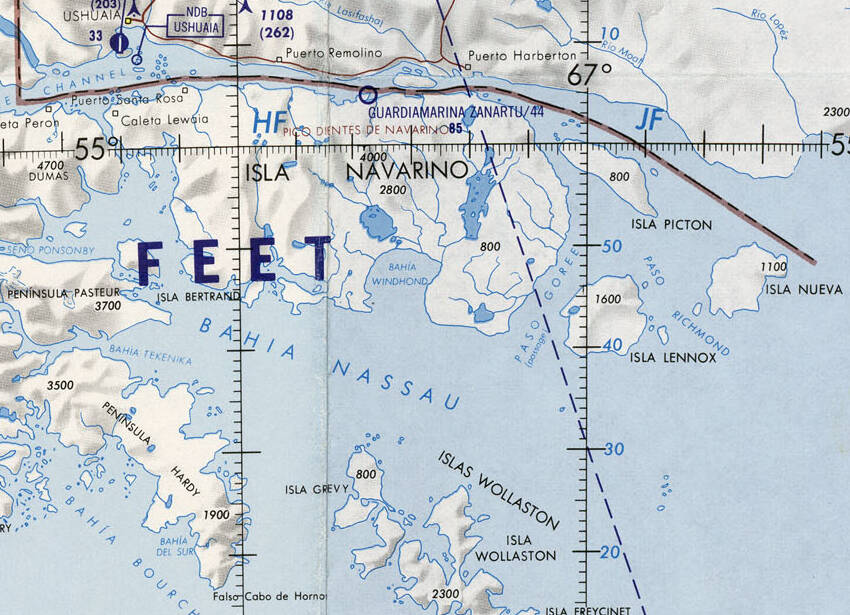

Isla Navarino and nearby islands on 1:1,000,000 aeronautical chart ONC T-18, from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

The below scan of a Chilean map shows Puerto Williams along the north shore of Isla Navarino, facing Canal Beagle or the Beagle Channal. Roads run either direction along the coast — west 54 kilometers to Puerto Navarino, a cluster of eight or nine houses and a ferry dock with connections across the channel to Ushuaia, Argentina, and east 28 kilometers to Puerto Eugenia, marked as a settlement and a minor port.

We were headed east, and you will see that Puerto Eugenia is a guy's house and a cove where he can ground his fishing boat.

Puerto Toro, further down the east coast, is a settlement of 36 people at the 2002 census, a cluster of houses around a ferry dock. There are some rough dirt or gravel lanes in the settlement, and a rough track leads inland to a point about 650 meters from the dock, and that's it.

Puerto Williams, with about 2,900 people, is the southernmost place in the world deserving the label of "town".

Picton, Lennox, and Nueva islandsThe red dots south of Puerto Williams are mostly sites of Anglican missions that operated between 1859 and 1916, plus a scientific outpost staffed for a year in the early 1880s, and a camp on Isla Lennox where over 800 miners, mostly Croatians, dug for gold in 1890.

Former and current settlements on Isla Navarino. The thin dotted red loop south of Puerto Williams around 1,170-meter and 1,195-meter peaks is a trekking route, not any sort of road. The white circles labeled "Est." or "Ea." are estancias, current or previous locations of a single dwelling. As for the purported airstrip on Isla Nueva, that seems to be a broad beach where a bush plane could land to service the lighthouse.

Start Out from Puerto Williams

There's more about the Yahgan and Villa Ukika near the bottom of this page. The short version for now is that Jemmy Button was a local native man, one of four people kidnapped by a British naval expedition in 1830 and taken to London to be exhibited as curiosities.

I was staying at Arturo's place, Refugio Jemmy Button. It's the last building along the paved road out of the southernmost town in the world. That makes it a short walk from the ferry ramp.

About a hundred meters past the refugio, the road changes to gravel. Another hundred meters beyond that, it passes the small settlement of Villa Ukika, the last community of the Yahgan people.

After our trip to the supermarket and returning to put away his purchases, Arturo said "Let's go for a ride." He said that he wanted to check on something, and because that day was some Supermoon Leap Tide event leading to an extremely low tide, this would be the very best day for quite some time.

OK, I had nothing specific scheduled for the day. Off we went, off the end of the pavement onto gravel as the Y-905 road roughly paralleled the Beagle Channel.

We pulled off after a while to look at the unusual forests of the far south.

The forests are different down here beyond 54° S. Some form of mistletoe is common.

Lichen and moss are abundant.

The ground was covered in moss and grass, not the waist-high shrubs I'm used to.

Also, trees were toppled and shattered, as if there has been a powerful explosion. Yes, an explosion of beavers.

National Geographic on the beaver invasionIn the 1940s, the government of Argentina decided that it would be a good idea to "enrich" Tierra del Fuego, their southernmost province, by introducing Canadian beavers. That could create a fur trade and attract human settlers.

In 1946, the Argentine Air Force flew ten pairs, just 20 beavers, from Manitoba to Tierra del Fuego. The beavers thrived, multiplying to an estimated 100,000 individuals and colonizing at least 70,000 square kilometers of territory. A 2019 study of satellite images counted 70,682 beaver dams on the Argentine side of the main island of Tierra del Fuego.

In North America, bears and wolves eat beavers. But there are no bears or wolves down here. The beavers soon crossed the border into the Chilean side of Tierra del Fuego, and swam south across the Beagle Channel to Isla Navarino. By the early 1990s, beavers had crossed the much wider Strait of Magellan with its strong currents to invade the Brunswick Peninsula around Punta Arenas, on the South American mainland.

Trees in North America have evolved defenses, such as re-sprouting after being chewed down, producing defensive chemicals, and tolerating wet and flooded soil. But these trees evolved in a beaver-free environment.

Argentina and Chile have tried to promote commercial trapping and recreational hunting, with very limited success. It's not the 1800s, there is very little demand for beaver fur and so it brings very little money.

The beavers support two other invasive species. Muskrats like to live in beaver ponds, and minks like to eat muskrats in addition to the native geese, ducks, and small rodents.

Researchers from New Zealand, which has been plagued by invasive species, have advised the governments of Chile and Argentina that complete eradication, which is enormously difficult and expensive, is the only real solution.

We returned to the car and continued out the road.

The End of the Road

The Y-905 road dwindled down to a dirt track, and eventually passed through a gate and cattle guard in a fence, where we stopped. Here's the view looking back.

I mentioned to Arturo that I had noticed a sign at the gate saying "Propiedad de la Armada". He scoffed, "Ahhh, we're the Navy."

We had reached the end of what Chile signposts from Torres del Paine National Park on south as the End of the World Highway. The is the end of the End of the World Highway. It reminded me of when I reached the northern end of paved road in Alaska, just over 15,000 kilometers away from here in a straight line. You can't drive the entire way between here and central Alaska. The governments of Panama and Colombia tried in the 1970s and 1990s to build a road through the Darién Gap, but stopped due to concerns about environmental damage and the increased spread of tropical and livestock diseases.

Here it is, what the above map showed as the town of Puerto Eugenia. Google Maps calls this Caleta Eugenia, a "Community Center". Really it's Eugene's cabin, two barns, and some sheds. The gate and cattle guard keep his cows from wandering away. We would continue on foot for another kilometer or two over the rise in the distance and beyond.

As for this being a port, you can bring in a fishing boat and ground it on the beach. But there's no pier.

Arturo noticed that Eugene was cutting some beaver-felled trees into planks, and made a note to contact him about buying some lumber for improvements to the refugio.

But it would be best to do that on a day when Eugene was there and the wild pigs weren't.

Lots of rope and floats for the crab traps.

The stacks of traps are for catching centolla, the Chilean king crab found in these waters. Disagreements between Chile and Argentina over fishing water boundaries led to the establishment of the Chilean Navy base that became Puerto Williams. The Navy and Coast Guard patrol the channel and open water to the south to keep Argentine fishing boats out of Chilean water.

We continued parallel to the shore, stopping to look back.

There were more beaver-chewed mistletoe-festooned trees.

Many of the beech trees on Isla Navarino have large parasitic fungus growths called llaullao or pan de indio. The fungus blocks the tree's sap ducts, and the tree generates defensive galls to bypass the blockages. The fungus then expands outward from that. The indigenous people ate it uncooked, and it was almost their only vegetable food.

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin had studied geology and natural science, and joined the second survey mission of the HMS Beagle in 1831–1836. The Voyage of the Beagle, the popular book he wrote based on the journal he maintained, records his observations of this fungus on Tierra del Fuego and surrounding islands.

We continued on, with one last look back at the end of the road.

Some of the trees are shaped like an umbrella, almost with a flat disk of leafy branches.

Flag trees are common in this region. I mentioned that it must be very windy much of the time here. Arturo said, "Mmmm, hundred-kilometer wind is normal, but sometimes two hundred." I was glad to be there on a rather calm day.

Remains of small sentry bunkers can be found here. They're shallow pits with decayed remains of logs for side walls and corrugated metal roofs. They look out across the Beagle Channel to the Argentine side.

These date back to the Beagle Conflict of 1977–1978, in which the military junta ruling Argentina wanted to seize the small and uninhabited Picton, Lennox, and Nueva islands from military-junta-ruled Chile, thus claiming a greatly extended exclusive fishing zone and, through that, a greatly extended claim over Antarctica. Argentina seems to have come within a few hours of an attack on multiple Chilean territories on 22 December 1978, although they have kept almost all information secret and it's still unclear precisely what did and didn't happen.

Harsh military outposts have been common in far southern Chile. The city of Punta Arenas was founded as a prison colony and military outpost where unruly or underperforming personnel were banished. Isla Dawson, south of Punta Arenas in the Strait of Magellan, became a slave labor prison camp where the military dictator Augusto Pinochet sent political prisoners to work and die. I don't think anyone ended up in one of these sentry posts as a reward for good behavior and performance.

On we went, down toward a distinctive spit of land. Ahead of us, we were looking further out Beagle Channel. Those contested islands and the opening out into the Southern Ocean were just out of sight around to the right.

This was close to the extreme point of an unusually low tide, caused by the Moon being near or at perigee, its closest approach to the Earth, while also aligned near or opposite the Sun. Such a "king tide" produces unusually high and low water levels. The narrow strip of beach ahead of us would normally be flooded.

Our goal was a tidal pool that only connected to the channel and thus the ocean during high tides.

Water in the tidal pool was unusually low, with a wide damp waterline and lots of algae.

Moss and lichen ruled above the high water line.

Beds with thousands of mussels were exposed.

This region experiences strong storms. A strong storm is associated with unusually low air pressure, providing a vacuum effect pulling more sea water into an area and raising the water level.

A whale had managed to get back into the tidal pool during a storm at an unusually high king tide a few months before. It was stranded, it died, and now its skeleton had been picked clean by birds. Today's extra-low king tide had its skeleton exposed.

Arturo began speculating on the ethical nature of taking a piece of the skeleton. He particularly had his eye on one of the long ribs, thinking it would look nice high on the wall of the shared room in the refugio.

I said that I couldn't imagine what use the Chilean Navy would have for a dead whale.

Arturo was happy with his whale rib!

The whale skeleton was around 54.93475 °S 67.29086 °W. This was the furthest south I had ever been. My maximum the other direction was 66.18533 °N in Iceland.

We were soon topping the rise on our return to his car.

Tierra del Fuego and its Inhabitants

Tierra del Fuego is Spanish for "Land of Fire". It's an archipelago off the southern tip of South America, the collection of islands south of the Strait of Magellan. There's the main island, divided between Chile and Argentina, and many smaller ones including Isla Navarino.

All I had ever learned about it was its location and the name and its meaning. If you had asked me about it, I would have figured that it had to do with the "Ring of Fire" around the Pacific. But no, there are no volcanoes in Tierra del Fuego.

"Land of Fire" is a literal description of what the early European explorers saw, but it is greatly complicated by their wild misinterpretations and the fact that the people living in this area thoroughly freaked out the Europeans for centuries. The early European explorers were overly aware of Greek myths of ύπερβόρεοι or Hyperborea, and had also read early 16th century Spanish chivalric romance novels, and so they were looking for exotic and amazing people living in polar realms.

The man English speakers call Ferdinand Magellan was a Portuguese navigator who led a 1519–1522 Spanish expedition around the world. He would have written his name as Fernão de Magalhães, and his Spanish crew called him Fernando de Magallanes.

His expedition came through this area in 1520, finding the passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific that became named the Strait of Magellan or Estrecho de Magallanes. He and his crew observed people that the Portuguese-speaking Magellan called Patagão and his Spanish-speaking crew called Patagón. They all believed that the locals were over twice the height of normal humans. And, naked, although that part was actually true.

The earliest human settlers arrived here around 8,000 BCE, becoming canoe-based hunter-gatherers. They adapted to and thrived in the local climate. They developed a significantly higher metabolism, and had little need for clothing, even during the winter. They dived naked into the icy water to collect shellfish. They slept naked in the open while the Europeans laid shivering under blankets in their ships.

Indigenous peoples of southern South America, from Wikipedia. English and Spanish scientists have different ways of spelling the groups' names, and they're different approximations to how they named themselves in their now extinct languages. Or, for the Haush, what seems to have been a derogatory name used by the Yahgan.

They did maintain many small fires, though, around the doorways of their simple shelters and in firepits within their canoes. So, this was the "Land of Fires".

The Europeans remained terrified of the naked giants, and remained far enough away that they didn't realize that they were normal sized humans. Later explorers, of course, reported seeing increasingly larger Patagonians, eventually reporting sizes up to nearly four meters in height. Rumors of giants in Patagonia persisted into the early 1800s, by which time the reports had become the subject of satire.

The Kawésqar people lived in the islands of the southern Pacific coast from Golfo de Penas to the south; the Selk'nam on the eastern half of Tierra del Fuego; the Haush or Manek'enk at the east tip of Tierra del Fuego; and the Yahgan people along southern Tierra del Fuego and on the islands south of there. There are multiple spellings of Yahgan, and sometimes the people are referred to as Yámana, the name of their language.

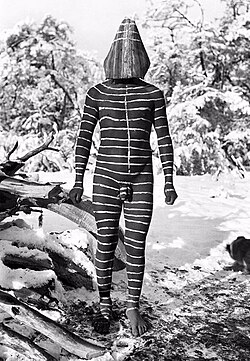

They all spoke different languages but had similar initiation ceremonies for young men. These ceremonies featured dramatic re-enactments of mythic events accompanied by tests for courage and resourcefulness. For the ceremonies, the adult men of all the groups wore nothing but paint and conical headdresses to portray sinister supernatural spirits. This, of course, scandalized the European intruders.

Selk'nam man prepared for a ceremony, from Wikipedia.

European representation of over-dressed gigantic Patagonians, from Wikipedia.

Robert FitzRoy was given command of the British survey ship HMS Beagle in 1828, after its captain fell into deep depression and committed suicide during the difficult survey of the waters around Tierra del Fuego. He seized four young Yahgan people and took them back to be exhibited in London as curiosities, as the English were prone to do.

The four were O'run-del'lico, El'leparu, Yok'cushly, a girl, and a fourth whom the crew never got around to learning his actual name. The crew assigned them fairly nonsensical names — Jemmy Button, York Minster, Fuegia Basket, and Boat Memory, respectively. As for Jemmy Button, the namesake of the refugio where I was staying, the crew made up that name because they claimed to have purchased him for a button. However, it was clear that they probably hadn't really offered anything in trade, and just kidnapped him. "York Minster" is the name of a church in England.

"Boat Memory" died of smallpox soon after arrival in England, but the other three survived despite being exposed to multiple pathogens that their immune systems had never encountered. They were taught to wear English clothing, and to speak the English language. They met the king and queen, and became celebrities.

FitzRoy had hoped to convert them to Christianity and send them back to assist Anglican missionaries. After one year of celebrity life in London, they joined Charles Darwin on the famous second voyage of the HMS Beagle, which ran from 27 December 1831 to 2 October 1836 and re-visited Tierra del Fuego on its circumnavigation of the world.

The three young Yahgans were happy to be returned to their homes in 1833, but the plan to Christianize the Yahgan people accomplished very little. In his book The Descent of Man, Darwin wrote that Jemmy Button and the other Fuegians had no concept of God or the Devil, and that Jemmy, "with justifiable pride, stoutly maintained that there was no devil in his land." Jemmy lived into the mid 1860s.

Despite the initial failure, Anglican groups made repeated attempts to establish Christian missionary stations in Yahgan territory. They finally achieved limited success at Ushuaia in 1869. However, British, Spanish, and Spanish-based Chilean and Argentinian settlers kept moving in from the north, bringing fatal diseases and massacring natives who dared to get in the way of sheep ranches.

The native people kept moving further south, and the missionaries relocated their stations. However, by the early 1900s the native people were effectively exterminated. The last mission station closed in 1916, as shown on the map near the top of this page.

Thomas Bridges,

the son of one of the original Anglican missionaries,

became fluent in the Yahgan language.

In the 1870s he compiled a grammar and a dictionary

of over 32,000 Yahgan words.

Thomas Bridges' English-Yahgan Dictionary

His son later compiled vocabularies for the

Selk'nam and Manek'enk languages.

References on these people

and their extinguished cultures and languages include:

Uttermost Part of the Earth,

E. Lucas Bridges, 1948

"Anglican Missionary Endeavour in Tierra del Fuego

(1832–1916)"

"Tierra del Fuego, Missionaries,

and Catechists"

The Anglican Church in South America,

E. F. Every, 1915

More recently, about linguistic fieldwork in

Isla Grande del Tierra del Fuego

and Isla Navarino beginning in 1964 with the last few

Selk'nam speakers and in 1985 with the few remaining

Yahgan speakers:

"A Genealogy of my Professors and Informants",

Anne MacKey Chapman, 2003, revised 2005

And, more recently yet:

"Plagues, past, and futures for the Yagan canoe people

of Cape Horn, southern Chile",

Maritime Studies, 2021

"From earth to sky: Large-scale archaeological

settlement patterns in southernmost South America

based on ground surveys, UAV LiDAR,

and open access satellite imagery",

The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology,

2024

https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2024.2426828

"Excavating a Language at the End of the World"

"Words as Archaeological Objects:

A Study of Marine Lifeways, Seascapes, and

Coastal Environmental Knowledge in

the Yagan-English Dictionary",

International Journal of Historical Archaeology,

2024

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-024-00729-7

Villa Ukika

Villa Ukika, a small settlement about 200 meters out the east road from where I stayed, has been the last Yahgan settlement at least since the 1960s.

Cristina Calderón, the last living full-blooded Yahgan person and the last native speaker of the Yahgan language, lived here until her death in February, 2022, from complications of COVID-19.