When the Sub-Mariner Was A Bowery Bum

In Which I Break Into Comicbook Writing

Or at least writing about comicbooks and not the comicbooks themselves.

My Fictional Architecture of Manhattan page has a picture and description of 177 Bleecker Street. That caught the attention of Roy Thomas, who created the character of Doctor Strange while living in an apartment in that building. He used his own address as the location of Doctor Strange's Sanctum Sanctorum.

Roy went on to create or co-create many Marvel characters including Woverine, Vision, Carol Danvers, Luke Cage, Iron Fist, Red Sonya, Adam Warlock, Morbius, Ghost Rider, Havoc, Thundra, Brother Voodoo, Valkyrie, and many others, and introduced the pulp magazine hero Conan the Barbarian to comics. Along the way, he became Stan Lee's first successor as editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics.

Roy is a major figure, and when he contacted me asking if he could use my pictures in Alter Ego, his Silver Age magazine, of course I said "Yes!" [Alter Ego, vol. 3, no. 138 (March 2016), pp 51-57]

I later pitched an article to him, combining the 1962 re-appearance of Namor the Sub-Mariner, one of Marvel's earliest characters, with pictures and descriptions of what you can see today of the 1962 (and earlier!) setting of that story.

My article appeared in the January 2023 issue of Alter Ego [vol. 3, no. 179, pp 24-28].

It had to be edited down, as I had included far more pictures than needed to tell the story, letting Roy and associate editor Jim Amash pick and choose. Here is the text of my article with those extra pictures and descriptions added.

When the Sub-Mariner Was A Bowery Bum

A Historical Look At A Primary Setting Of

Fantastic Four #4

A/E EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION:

Back in issue #138, journalist Paris Liu provided a history

of 177A Bleecker Street and environs in

New York's Greenwich Village—the address,

of course, of Doctor Strange, Master of the Mystic Arts

(and, no so incidentally, the real-world locale where

fellow pros Gary Friedrich, Bill Everett,

and Roy Thomas had dwelt for half a year

in 1966-66).

That article and his own interests led A/E reader

Bob Cromwell to take a long and informative look

at an even earlier, basically true-life Marvel

landmark—the "flophouse" in the Bowery

sector where, in Fantastic Four #4

(May 1962), a disgruntled Johnny Storm,

a.k.a. The Human Torch, decided to temporarily hide out

from the other members of that fledgling super-hero

team.

Only, it wasn't really a "flophouse" (not that Johnny

or scripter Stan Lee used that precise phrase),

as Bob explains below

Unfortunately, we were forced to abridge Bob's

article slightly, and to utilize only half or so of the

numerous photos that accompanied it when it was first

posted online at

https://cromwell-intl.com/namor—but,

if you want, you can revel in the entire piece and

all the images by clicking on that still-valid URL.

Meanwhile, here is the Alter Ego

version, with thanks to Bob C. for making it

accessible to our ever-questful readers...

What you're looking at here is actually what I submitted plus some wonderful additions by the Alter Ego editors and several improvements they made to my prose, and also some updates from 2020-2022 while the article was making its way to press while the COVID-19 pandemic killed off yet another business.

I was at a Ukrainian dive on the Lower East Side when the guy on the adjacent bar stool asked a question that led to American history throughout the 20th Century, the return of Namor the Sub-Mariner in the Silver Age, and, just possibly, Thor's search for Odin.

Who said the comics weren't educational?

I was at Karpaty Bar on Second Avenue near 9th Street. Dave on the adjacent stool asked me if I lived in the neighborhood. No, I'm from out of town. But I get to New York fairly often, and my local home away from home at the time was the White House nearby on Bowery. He was surprised to hear that, as knew what the place was like when the Sub-Mariner lived there or somewhere very similar.

The White House had been home for indigent men since 1899. Around 2000 it was converted, half for permanent residents and the other half a hostel for independent travelers. It was a few years afterward that I started staying there, on the hostel side. It was a little scruffy, but you got a tiny private room for only $30 in Manhattan. But the Sub-Mariner?

Decades before the 1962 re-emergence of the Sub-Mariner, the family of Jacob Kurtzbert / Jack Kirby lived at 142 Essex Street, in the red brick building with the blue "Lazar Mechanical" sign. It's just a few blocks east of Bowery.

The Sub-Mariner in the Bowery

In Fantastic Four #4, cover-dated May 1962, Johnny Storm has left the Fantastic Four. He goes to the Bowery to find a place to stay. This was during a period when Marvel was moving toward a realistic New-York-based setting. No more Central City, but actual New York settings and details.

Page 8 of Fantastic Four #4, May 1962.

Notice the elevated train in the background of the first

panel, that was the IRT Third Avenue Line

or the Third Avenue Elevated,

which opened through the Bowery area in 1878

and was shut down and demolished in 1950–1955.

It would have been familiar to FF readers in 1962

from appearances in movies and art.

In the second panel see the "MEN'S HOTEL" sign which

seems to continue downward to say 25¢ a night

for a place to sleep.

That would probably be a rather low price for 1962,

but then he was in the heart of Skid Row.

The residence is between low-cost clothing shops,

a long-time specialty of the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Johnny selects a place "no worse than the others". Once inside, things become almost Deadpool-level meta.1 He finds an old comicbook from two decades before—an issue of Timely's Sub-Mariner. It's an "old, beat-up comic mag...from the 1940s." But Johnny remembers his older sister Sue Storm talking about Namor as an actual person. (This was from the early days when Sue Storm had been supposed to be alive during the Second World War.) One of Johnny's fellow flophouse bums comments that someone very similar is living there at that very moment.

In FF #4, Johnny Storm,

on the lam from his teammates,

winds up the the decidedly low-rent Bowery area of Manhattan.

He soon discovers that his new digs stock at least one

20-year-old comicbook, a Sub-Mariner Comics

whose cover doesn't match any actual Golden Age illustration.

Script by Stan Lee; pencils by Jack Kirby; inks by Sol Brodsky.

Thanks to Barry Pearl for the research.

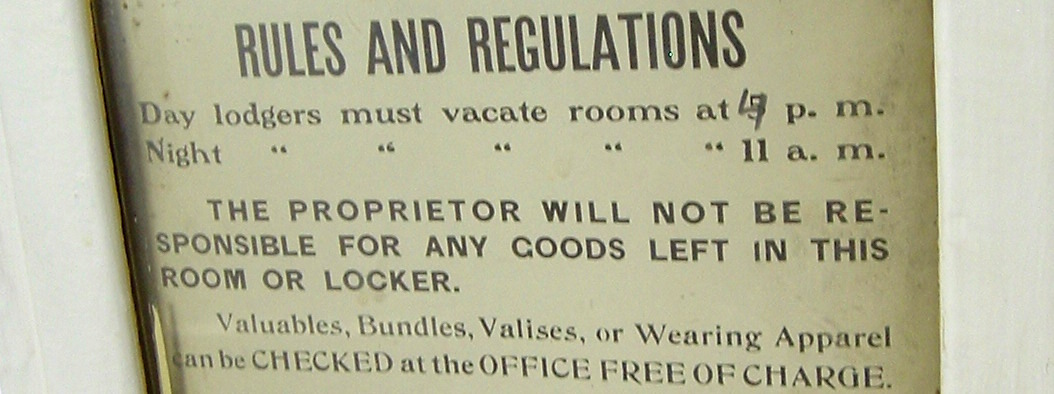

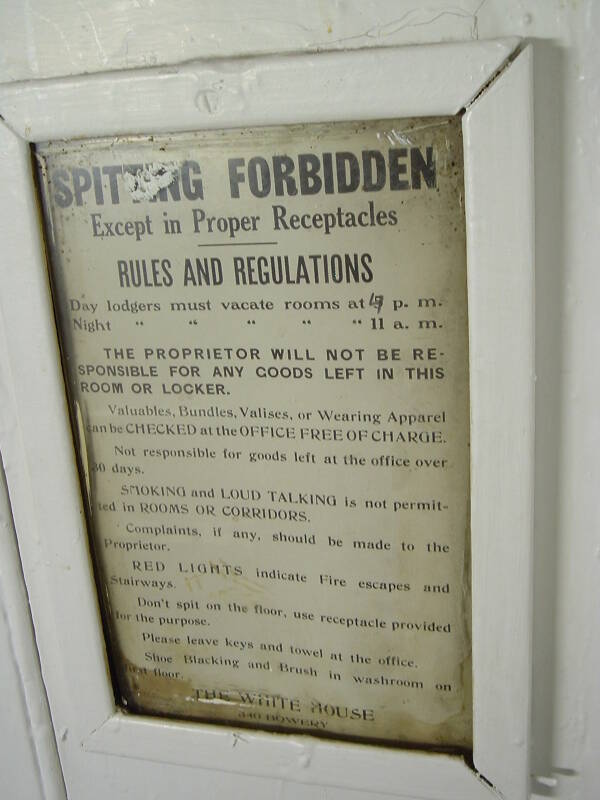

The "RULES" sign on the wall has its equivalent in the

one seen below in the White House, a similar locale

described further along in this tale.

This photograph was taken in the White House in April 2006, when half of the facility was an SRO for permanent residents, and the other half operated as a hostel where I frequently stayed. The sign probably dates back to the 1930s or 1940s. By the 2000s, a newer sign on the permanent resident side started with "NO SCREAMING, NO FIGHTING."

Hang On—What's The Nomenclature?

First, "the Bowery". That's the English spelling of a now archaic Dutch word Bouwerij. The Dutch established the settlement of Nieuw-Amsterdam at the southern tip of Manhattan island in 1624. By the mid-1600s there were several large farms north of the settlement. The Dutch called the area and the road leading through it "Bouwerij", meaning "farm". The British took over the territory in 1664, renaming it "New York" and spelling that Dutch name "Bowery".

By the early 1800s the city had grown. Wealthy residents' homes replaced farms, and the Bowery became the theater district. The city continued to expand, with the wealthy moving to follow the northern edge. By the 1860s, the Bowery's classy theaters were changing to low-brow music halls, beer gardens, dime museums, gambling parlors, and brothels.

Now, "flophouse bum". Low-cost residential choices of SROs, dormitories, and flophouses were occupied by hobos, tramps, and bums.

Hobos were skilled laborers who rode freight trains to follow seasonal work. Western expansion had scaled back through the 1910s with the addition of Arizona and New Mexico as the 47th and 48th states in 1912. Then the Great Depression started in 1929, bringing an end to most itinerant work.

Tramps, some of them recently-unemployed hobos, traveled by freight train but didn't work, at least not very much.

Bums didn't even travel, they were the stationary unemployed.

An SRO or Single-Room Occupancy hotel had small private compartments, maybe just six by four feet. They were often called "cage hotels" because the compartment walls didn't reach the floor or ceiling. Wooden lattices or chicken wire kept men from crawling or climbing into adjacent "cabins". The cage design greatly simplified (and thus cheapened) heating, ventilation, and lighting. Once safety codes began requiring fire suppression, a few sprinkler heads covered an entire floor.

A dormitory had one or more large open rooms with several beds or cots.

A flophouse charged even less to flop on the floor and sleep indoors.

Technically, Johnny in FF #4 was in a dormitory, surrounded by bums. But I am not going to correct Roy Thomas on this! He used "flop-house" to describe the location when re-telling the story of Namor's re-discovery in Sub-Mariner #1 (May 1968, pencils by John Buscema, inks by Frank Giacolia).

World Wars and the Depression

Many hotels in the Lower East Side of New York were converted to SROs around the end of World War I. Men returning from Europe were processed out in New York. They were given enough to stay for a short time before making their way home. However, many checked into SROs and never left.

Bowery, today's southern extension of Third Avenue plus a few blocks to either side, became the city's Skid Row during the Great Depression. The indigent population peaked around 75,000 in the 1930s. SROs, dormitories, and flophouses filled the upper floors of many of the buildings along Bowery.

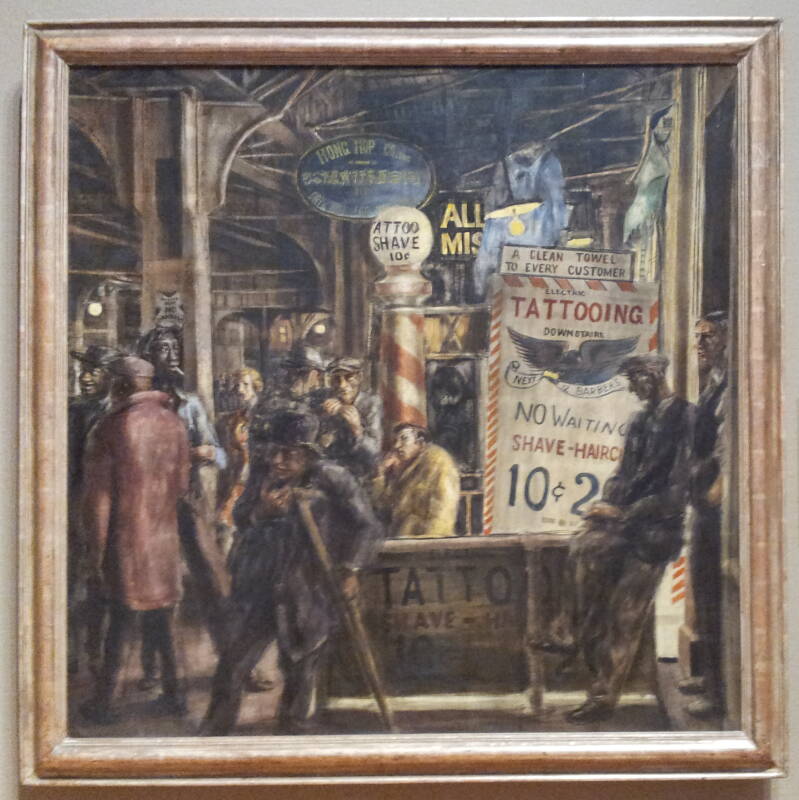

Reginald Marsh painted scenes of Depression-era New York. His painting The Bowery (1930), now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, shows a typical scene. The Third Avenue Elevated line runs overhead, making things even darker, dirtier, and noisier. The "El" ran down Third Avenue and the Bowery from 1878 until 1955.

The Bowery, 1930, by Reginald Marsh

(1898-1954), in the collection of the Metropolitan

Museum of Art.

The placard reads:

Marsh's scenes of Depression-era New York

highlighted the hobos of the Bowery,

where he frequently sketched.

Using a brown palette, Marsh painted this

crowded scene of the down and out standing

along the Bowery surrounded by signage and

the Third Avenue El above.

In 1929 Benton introduced his close friend

Marsh to egg tempera, and from 1929 to 1940

it became his preferred medium for major

works such as "The Bowery".

Marsh's rhythmic and often bawdy compositions

were influenced by Renaissance and Baroque

masters but nonetheless deeply rooted in the

harsh realities of 1930s America.

Tattoo and Haircut, 1932, by Reginald Marsh

(1898-1954), in the collection of the

Art Institute of Chicago.

The placard reads:

Of the foremost realists of the 1930s,

Reginald Marsh was fascinated by public behavior

and the exciting commotion of New York.

"Tattoo and Haircut" portrays a busy scene

of people below the massive structure of

the El on the Bowery,

then an area notorious as a skid row.

Rendered in Marsh's gently satirical style

are several city types: a derelict on crutches,

loitering men conversing or smoking cigarettes,

a chic woman walking by herself.

Marsh used an egg tempera medium to fill

every inch of the composition with details,

from architectural elements to sign and text.

Introduced to the artist by the muralist

Thomas Hart Benton, the medium suited Marsh's

keen skills as a draftsman.

Here he added successive films of tempera in

muted colors, using its mottled, uneven

surface to emphasize the grimy nature of

this world.

His technique thus reinforces his presentation

of the subject: cacophonous, dilapidated,

and dim, yet vibrantly alive.

Wolverine Noir (2009), the Marvel Comics limited series by writer Stuart Moore and artist C. P. Smith, is set in the Bowery in 1937. James Logan is a private detective with an office under the 3rd Avenue El.

Meanwhile, Jack Kirby and Stan Lee were observing the Bowery and the rest of New York through the 1930s. The American public had seen the Bowery depicted in film since the 1930s, including the evolving film series that featured first the Dead End Kids (1937-1940), then the East Side Kids (1940-1945), and finally the Bowery Boys (1945-1958). Comics writers and artists wrote and drew what they observed, and what their audiences would recognize.

Jack Kirby drew cartoons for Lincoln Newspaper Syndicate in 1936–1939, and in 1939 (at age 17) Stan Lee (born Stanley Lieber) became an assistant at Timely Comics, which would later become Marvel Comics.

Stan's family lived in northern Manhattan and he attended high school in the Bronx, but the Kirbys lived at 147 Essex Street just a few blocks east of Bowery.

Another wave of demobilized men moved into SROs at the end of World War II. However, the G.I. Bill of 1944 was a huge help. The Bowery indigent population fell to about 15,000 by 1949. Even so, the area remained Skid Row into the 1980s. In 1962 Johnny Storm was in a notoriously bad part of town.

Sub-Mariner Unmasked

Namor the Sub-Mariner was originally an agent of chaos, almost like Loki (of whom more later). But during the U.S. involvement in World War II, Namor was of course on the side of the Allies.

The Golden Age Sub-Mariner Comics, as well as his appearances in Marvel Mystery Comics, lasted through June 1949. The Sub-Mariner disappeared in the post-WWII era when superheroes were largely replaced by horror, war, and romance storylines. The character was briefly revived for two years in the mid-1950s, and then disappeared again... for what turned out to be approximately seven years.

Which brings us to 1962 and Fantastic Four #4. A mysterious bearded resident has been living on the Bowery for several years. He displays uncanny strength and fighting skill, but he can't remember who he is or why he is there. Intrigued, Johnny burns off his overgrown hair and beard—and discovers that he is Namor the Sub-Mariner... a character about whom, only a few moments before, by an amazing coincidence, the young Torch had been reading in that old, dog-eared comicbook!

Johnny carries Namor out to sea and drops him into the water. The Sub-Mariner's memory returns once he's back in his native element. Discovering that atomic testing has destroyed his native Atlantis, Namor vows revenge upon humanity. The Fantastic Four must reunite and stop him—on the piers and docks of New York City, but no longer on the Bowery.

A 1968 comics story revealed that Namor had been made amnesiac by a foe in the mid-1950s. FF #4 in 1962 is the character's recovery from that injury—and his return to publication.

The original Human Torch, who was actually an android, had made his debut in Oct 1939's Marvel Comics #1, published by Timely Comics. the same magazine and issue in which the Sub-Mariner first appeared. So it's appropriate that Namor reappears in the company of a second (and entirely human) Human Torch.

The title changed to Marvel Mystery Comics with issue #2, and a battle between the two characters spanned issues #8 and #9. Timely's top three Golden Age characters were the Human Torch, the Sub-Mariner, and Captain America.

What Can You See And Experience Today?

If you know what to look for, many former SROs and dormitories still stand along the Bowery. Here are two a short distance north of Houston, in the low single digit streets of Manhattan's grid.

300 Bowery was the Hotel Defender, an SRO. It's in the first block north of Houston, just south of 1st Street. Now a shop on the ground floor sells cappucino machines.

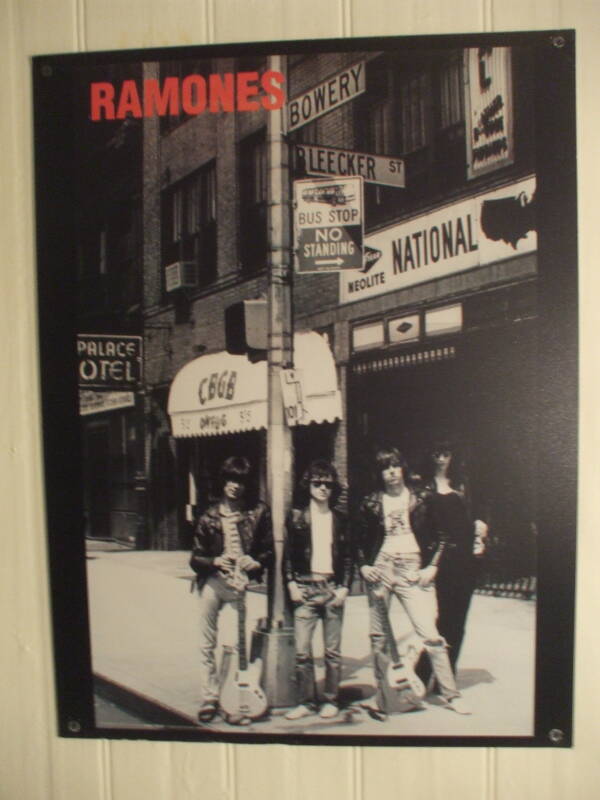

CBGB, associated with the Ramones (seen here), the Talking Heads, Blondie, and other New York bands of the 1970s, was on the ground floor of the Palace Hotel, another SRO. It was on Bowery, across from where Bleecker Street emanating from Greenwich Village comes to an end. CBGB closed in 2006 after a long rent dispute, and became a designer clothing store.

Here's a view north past CBGB on Bowery in March 2005, with the Empire State Building about 30 blocks north. The last show was on October 15, 2006.

But what about more than looking from the outside?

What about experiencing one of these places?

Some former SROs, which may have been dormitories or even flophouses without beds or cots, have been converted to low-cost hotels. They have been marketed as hostels, with shared toilets and showers, but with the SRO cabins as private rooms.

The White House at 340 Bowery

One example through the 2000s was at 340 Bowery. In 1899 a flophouse (or possibly dormitory) named the Bellevue Hotel was operating here. In 1905, a census recorder listed 70 men living at the address.

Eusebio Ghelardi, an Italian immigrant, purchased the property at 340 Bowery in 1916–1917. He renamed it the "White House", a name reflecting the Ghelardi family's racial policy through most of the 20th century. That same year he added a two-story extension to the rear.

In 1928–1929 he expanded onto the lot to the south, 338 Bowery, and built a unified brick façade across 338–340 Bowery. That's the dark brick structure at center here.

By 1950 there were 234 cubicles or cabins in the combined structure. They were 6×4 foot private spaces, with walls that stopped well short of the ceiling. Chicken wire mesh was fastened across the tops to keep someone from climbing over the divider into another cubicle.

The Ghelardi family sold the property in 1998. The number of permanent residents was rapidly dropping, so the new owners converted the original section into cheap lodging for independent travelers. It was cleaned, refurbished, and started operating as a hostel around 2000.

The closest section, with triple windows above

a ground-floor shop, was the permanent resident

section in the 2000s.

The red door was the emergency exit

at the bottom of the staircase,

which was behind the column of single windows.

The far section, with the blue door

and another column of triple windows

behind the fire escape,

was the transient side where

independent travelers like me could stay.

Everyone entered through the blue doors into the shared lobby room that looked out onto Bowery.

Keys were kept behind the desk. Keys were attached to a wooden rod, like a short section of broom handle. You couldn't put it in your pocket and forget to leave it at the desk as you were leaving!

A door into the residential side is at left, and one into the transient side is at right at the far end of the landing.

One of your two keys opened the door from the staircase into either the resident side or the transient side.

The passages between the cabins were narrow, and dimly lit.

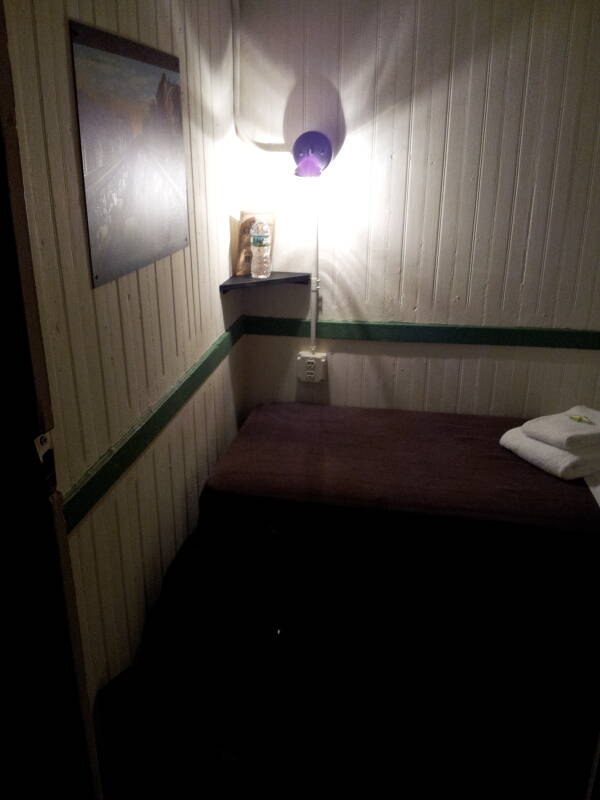

Your second key opened the door into your cabin. Here's mine.

This is the entire cabin, about four feet wide and not quite six and a half feet long. The bed is a shelf fastened to three of the walls, with storage space underneath.

The compartment walls reached the floor, but not the ceiling. Wooden trellis material formed the tops of the walls and the cabin's ceiling. It was chicken wire mesh before this half was renovated as a hostel.

Each cabin had a deadbolt lock.

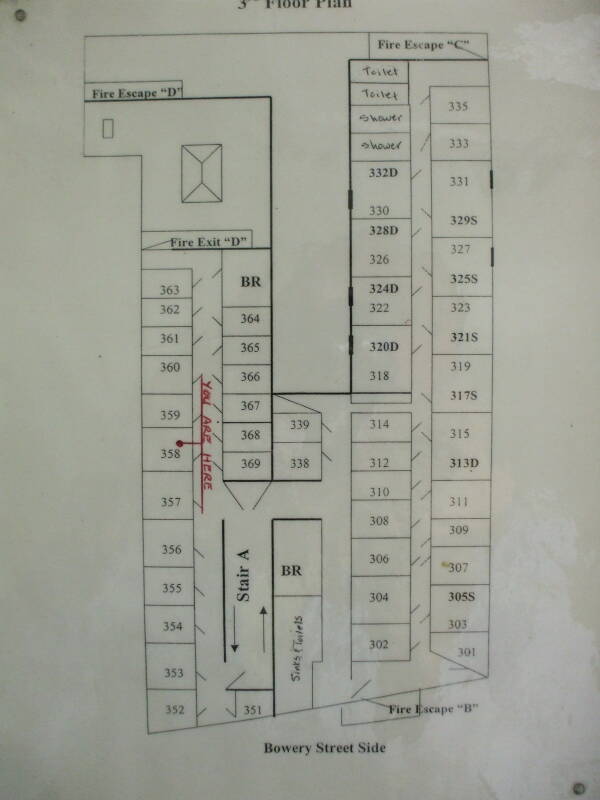

This floor plan was posted in the wrong place.

It was intended for room #358

on the permanent resident side.

I photographed this in my cabin

on the transient or hostel side.

Rooms 301–339 are on the transient or hostel side.

Rooms 351–369 are on the permanent resident side.

One of your two keys opened the door from the stairway

into either the resident or transient side.

The other opened the door to your cabin.

As in any flophouse, dormitory, or SRO, plumbing was shared—sinks, shower stalls, and toilet stalls. These are much cleaner and better maintained than on the residential side, which were much like what they would have been back in 1962.

Returning to your cabin at night, Bowery still has a little bit of a Reginald Marsh vibe.

The White House transient side, the hostel, closed from September 2009 until January 2011. Further renovations were needed to get up to code for hotel/hostel standards. Then it shut down again, apparently forever, in September 2014. The end was near. Just a few permanent residents remained. Mac, with the unmistakable Marine Corps bearing and cap. Lou, from whom diabetes had taken half a leg. Maybe six men total.

But there was still a place where you could channel your inner Sub-Mariner or Human Torch, just three blocks further down Bowery...

The Prince Hotel Became The Bowery House

The Prince Hotel at 220 Bowery opened as a conventional hotel in 1927. Around the end of World War II it was converted into an SRO to pack in the soldiers arriving by troopship for processing out of the military. The G.I. Bill of 1944 made things much better than after the First World War, but there were still many men who checked in and never left. The Prince Hotel is the lighter brick building, eight windows wide, in the left half of this picture.

220 Bowery, the former Prince Hotel and then the Bowery House in the 2010s, on the left. On the right, taller and more elaborate, is the former YMCA where William S. Burroughs lived.

The darker brick building at right is the former YMCA. That organization had moved out by 1970, when the area was still Skid Row and the Prince was an SRO. The writer William S. Burroughs lived in the ex-YMCA in "The Bunker", an apartment in the windowless former locker room. He appreciated its physical security, no windows and a locked gate and two more sturdy locked doors between his home and Skid Row. Burroughs lived there from 1974 until 1981. He knew all about the SROs, living next-door to one and undoubtedly spending time in some as a resident.

I lay there in my open-top cubicle room looking at the ceiling. ... I listened to the grunts and squeals and snarls ...

— Naked Lunch

The Prince Hotel was renovated and reopened in 2011 as the Bowery House, a low-cost hotel for travelers with a taste for history. For about $60-80 per night you could stay in a "cabin" or compartment still in the mid-1940s design. It became my new pied à terre through the rest of the 2010s.

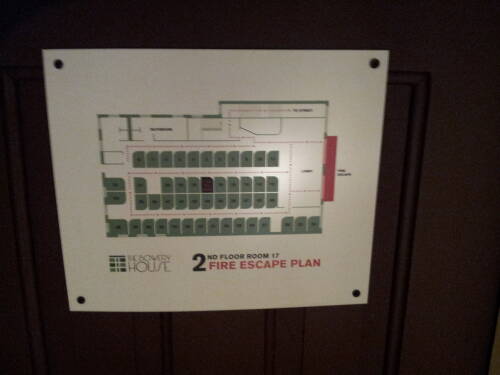

We're on our way to the front desk. Reception is on the third floor, cabins are on the second, third, and fourth.

The passages upstairs at the Bowery House were a little wider and a little dimmer.

Here's my cabin. The cabins were a little larger than those at the Whitehouse. They also had electrical outlets. That was a nice upgrade from the White House, where you had to leave your electronics down at the front desk for charging.

You were provided with a hand towel and a bath towel. You were also given a bottle of water and a pair of small foam earplugs.

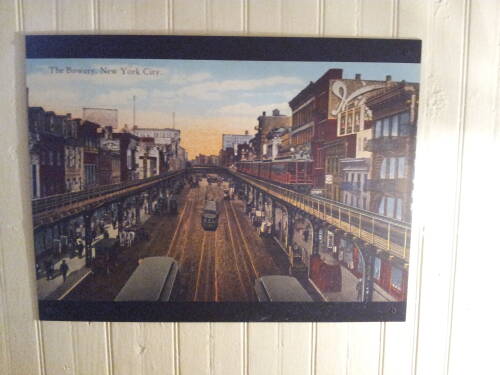

Each room had Bowery-specific artwork — old photographs or paintings of the Bowery, a photograph of The Ramones in front of CBGB, or a related movie poster like Bela Lugosi's Bowery at Midnight. Notice the Third Avenue Elevated line depicted on a postcard enlarged to decorate my cabin. That's what was in the background of that panel showing Johnny Storm's arrival in the Bowery.

There were lounge areas on the second and third floor, but since there is so much to do in New York City, not many people want to hang around where they're staying.

In the 2010s there were still three or four permanent residents who had been living there since the 1970s.

The Bowery House was a clean and safe place to stay. Some very cheap hotels a few blocks further down Bowery into Chinatown have recently been converted from SROs.

Online booking sites don't make their history and current state clear. They're not nearly as clean or carefully rebuilt. The Bowery House staff told me about guests who started their visit to New York in one of those places, and found that the move was a big upgrade.

The last of the SROs are closing and missions are moving out. The Bowery Mission is right across the street from the former Prince Hotel. The Bowery Mission was founded further south into Chinatown in 1879. It was the third rescue mission established in the U.S. and the second in New York City. The Salvation Army had a location next door to the Bowery Mission, but they moved that branch to Brooklyn.

The Bowery House was killed off in 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic. When I next traveled to New York, in 2022, I found a new pied à terre in another converted SRO. It seems that some permanent residents also remain there.

To Learn More

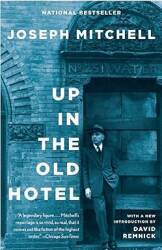

Joseph Mitchell's book Up In The Old Hotel is a collection of his articles in The New Yorker. Many of them involve various "characters", eccentrics and the indigent living in the Bowery and Greenwich Village.

I have a series of pages that go into much deeper detail on flophouses, dormitories, and SROs, mostly in New York but also in Chicago and elsewhere.

So, How Were Loki & Thor Possibly Involved?

The modern-day Marvel version of Loki first appeared in Journey into Mystery #85 (October 1962), solidly Silver Age. Of course, the current Marvel Cinematic Universe makes and enormous number of changes, but Thor: Ragnarok in 2017 originally had a connection to or at least an homage to FF #4.

First, see the mid-credits scene in the first Doctor Strange movie (2016). Thor is visiting the Sanctum Sanctorum. The Sorcerer Supreme is peeved that Thor brought the rather dangerous Loki to New York. Thor explains that it's "a long story, family drama, that kind of thing. But we're looking for my father." They will return to Asgard as soon as they find him.

The original screenplay for Thor: Ragnorak had Odin lost in New York and unaware of his own identity. Thor and Loki found Odin in an alley, confused and indigent. Photographs of the filming process and early trailers depicted that New York setting and Odin’s disheveled appearance. That scene and related ones were re-shot (or at least the CGI was re-done) to place the reunion in Norway, in order to better reflect the emotions of what’s happening and to retain Odin’s dignity.

Hela catches Mjölnir in a New York City alley, in a preview included on the Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 DVD, released a few months before Thor: Ragnarok appeared in theaters.

Hela destroys Mjölnir in a New York City alley, in a preview included on the Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 DVD, released a few months before Thor: Ragnarok appeared in theaters.

However, until that re-write and re-shoot, the 2017 movie re-created the Silver Age return of the Sub-Mariner—an amnesiac superhero living anonymously in a Bowery SRO, dormitory, or flophouse!

The AE editors added a sidebar in which they commented on Odin being lost and amnesiac in Thor: Ragnarok.

Probably by coincidence, isn't this like the situation in the TV series American Gods, based on a 2001 novel by Neil Gaiman, which debuted the same year Thor: Ragnarok was released, featuring its aged wanderer "Wednesday"—who's named after a day named for "Wotan" a variation on "Odin"?

And, by an even weirder coincidence, Ye Editor (Roy Thomas) had been trying since the 1990s to sell to DC Comics a modern-day sequel to the graphic-novel adaptation he and artist Gil Kane had done of Richard Wagner's four-opera Ring of the Nibelung, which would also have featured an Odin wandering about NYC years after the Norse Twilight of the Gods. Small world, no?

USA Travel Destinations

Back to International Travel

1: "almost Deadpool-level meta" became "very self-referential" in Alter Ego, which focuses on the Silver Age (1956–1970) while Deadpool first appeared in February 1991.