Stone Buddhas of Usuki

A Train and Foot Pilgrimage to the Stone Buddhas, a National Treasure of Japan

The Stone Buddhas of Usuki are a

National Treasure of Japan.

Most date to late in the Heian period

of 794–1185 CE,

while a few were created early in the Kamakura period

that began in 1192.

So, roughly, around the late 12th century CE.

These artworks were largely forgotten soon after the

last ones were carved.

In following centuries, various legends formed about

them and prominent figures who had lived

several centuries before the statues were carved,

figures who very likely were legendary themselves.

These are magaibutsu,

bas-relief images of the Buddha

carved directly into a cliff face.

They're carved into a layer of tuff formed by

pyroclastic flows from

Mount Aso

about 90,000 years ago,

ash and gas ejected at hundreds of kilometers per hours

and at temperatures up to 1000 °C.

Tuff is relatively soft, easy to carve,

but then it erodes easily.

Many of the lower bodies are partially or completely missing.

It's an easy trip from where I was staying in Ōita.

It's a train ride of about 40 minutes to Kami-Usuki Station,

and then a 4.5-kilometer walk that takes about an hour.

Google Maps dynamically generates the map when you load this page. Depending on what time it is in Japan, you may see buses by a different route instead of my rail trip. I went by train, east from Ōita Station along the coast, then south to Kami-Usuku Station, a ride of 35 to 45 minutes.

By Train to Usuki

I had walked from my hotel to Ōita Station, bought a ¥660 ticket, and boarded the local train. Before long we had stopped at Kōzaki Station where I had disembarked on an earlier day to visit the Tsukiyama kofun. I stayed on the train as it continued to the south.

The only railway staff on board was the engineer. Board and exit at the front so you can buy a ticket if you're boarding at an unstaffed station, and show the engineer your ticket as you disembark.

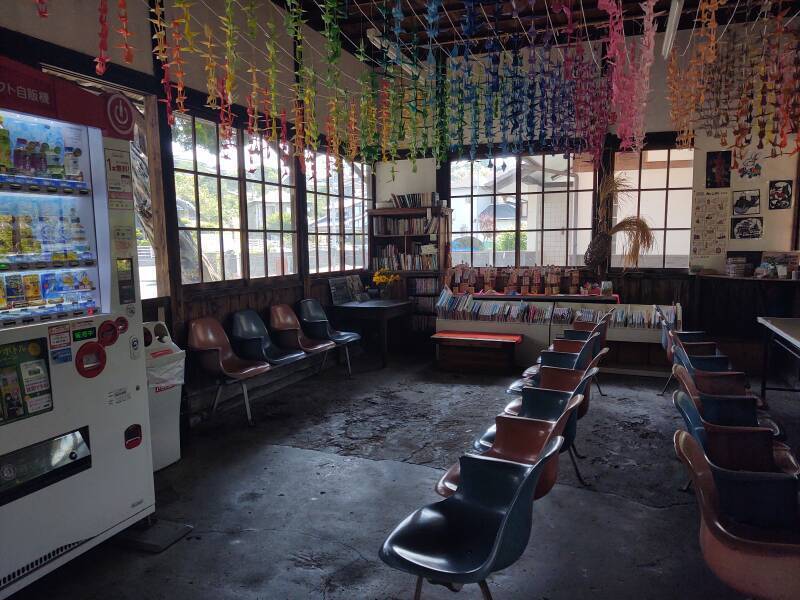

I got off at Kami-Usuki Station, where the waiting area has many seats, multi-colored origami cranes hanging from the ceiling, and a large collection of books.

Japanese school kids go to school and back home again on their own. This gives them a place to sit, and books to read, while waiting for the train.

Outside, over a hundred bicycles were parked in orderly rows. None had locks, none are needed here.

Walking to the Stone Buddhas

It's an easy walk of 4.5 kilometers, about an hour, from the station to the Stone Buddhas. Most of it is along highway 502, parallel to the Usuki River so it's almost entirely level.

There are many of the usual edge-of-town businesses until the road approaches the river. You pass under a high expressway bridge and then you're in agricultural land. Rice was being harvested during my visit in the middle of May.

There's a stone monument about two meters tall overlooking that rice field. It has large characters spelling "Fuku-zuka" on the side facing the highway, and a lot of text on the other faces.

The local people built it to honor Fuku Hikida. He had observed that every time there was heavy rain, the Usuki River would breach its levees and flood the rice fields. He came up with a levee design that diverted the water flow instead of attempting to directly block it. His levees withstood the high water and protected the rice fields.

He died in 1729, the monument was erected in 1838.

Part-way from that monument to the Stone Buddhas, I passed a statue of Jizō.

He's a bodhisattva typically depicted as a monk carrying a staff and a wish-fulfilling jewel, standing on a lotus base symbolizing his release from rebirth. He vowed to instruct all beings in the era from the death of the historical Gautama Buddha until the arrival of Maitreya. He's one of the four principal bodhisattvas in East Asian Mahayana Buddhism.

Jizō is regarded as the guardian of children and the patron deity of deceased children. He's Jizō in Japanese, Kṣitigarbha in the original Sanskrit.

People will dress a Jizō figure in a red bib and kerchief as an act of devotion or thanks.

The Stone Buddhas

You turn off the highway into a valley containing Mangetsu-ji, the Mangetsu Temple. The Stone Buddhas are on the steep slopes to your right as you buy your ticket and enter the park.

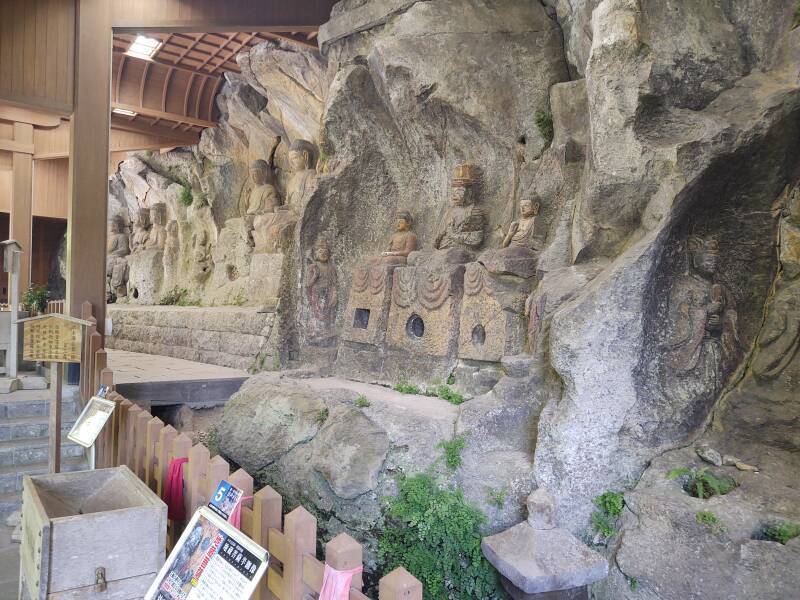

There are over seventy Stone Buddhas. Many are missing parts due to the centuries of inattention. Buddhism highlights the impermanence of existence, and so the damaged state fits. But for official designation as a National Treasure, the Ministry of Education required some restoration and the construction of protective covers.

The local legend says that a Buddhist priest named Renjo came from China to create the Stone Buddhas. Another legend says that they were inspired by Renjo, but created by a wealthy charcoal magnate named Manano Chōja to mourn his daughter who had died at a young age. The legend mentions Emperor Yōmei, known for supporting both Shintō and Buddhism, placing these stories in the 580s CE.

However, the artistic style of the artwork places most of these statues late in the Heian period of 794–1185 CE, and some early in the Kamakura period that began in 1192.

Soon after that, people became less interested in religious pilgrimages to Buddhist sites, and these statues were forgotten outside the immediate area.

Who's Who?

The carvings depict bodhisattvas, Amida Nyorai, Miroku Bosatsu, and others. Who are these figures?

There are many Buddhas, meaning that the Buddha manifests in many forms.

A bodhisattva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi or awakening, on the path to Buddhahood. In Mahāyāna Buddhism, one of the three main branches, the predominant one in Japan and elsewhere through East Asia and much of Southeast Asia, a bodhisattva is a spiritually heroic person with great compassion, working to attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings.

Nyorai is the Japanese translation of the Sanskrit and Pāli word Tathāgata, which was the term the historical Buddha used most often to refer to himself.

Amitābha, called Amida in Japan, is the principal Buddha of the Pure Land school of Mahayana Buddhism.

So, Amida Nyorai is the Japanese name for the Tathāgata Amitābha, the primary manifestation of the Buddha within the Pure Land school.

Dainichi Nyorai is the Japanese name for Vairocana, a cosmic Buddha.

Miroku Bosatsu is the Japanese name for Maitreya, the bodhisattva who is regarded as the future Buddha.

The First Cluster of Stone Buddhas

Stone Buddhas Web Site sekibutsu.com mapMake sure to pick up a map when you buy your ticket. You can also get a map online.

Confusingly, the first and second clusters you reach are labeled "2nd" and "1st", respectively, on the maps. This section is about the first cluster you reach when you continue to your right past the ticket-checking booth. It has two niches of statues. Its statues were carved late in the Heian period, which began in 794 when Emperor Kammu moved the Imperial Court from Heijō-kyō, today's Nara, to Heian-kyō, today's Kyōto, and lasted until 1185.

The Nine Amidas are the first group, referred to as Kubon-no-midazou. A seated Amida Nyorai is in the center, with four relatively smaller standing statues of Amida Nyorai on either side.

The second niche has a large seated statue of Amida Nyorai, with bodhisattvas standing on either side. The group is referred to as Amida-san-son-zou. Some art historians feel that the central figure here is actually Miroku Bosatsu, the Maitreya.

The Second Cluster of Stone Buddhas

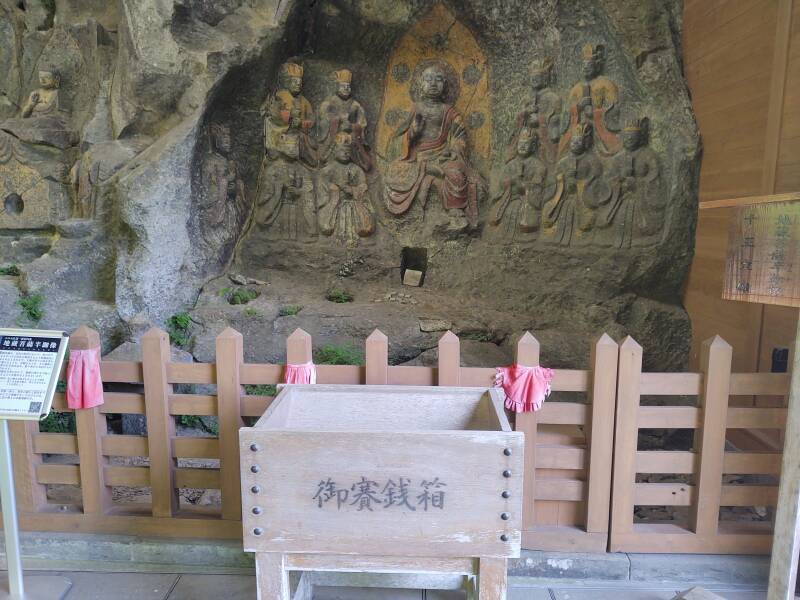

The second cluster has Jizō and the Ten Kings of the Underworld, referred to as Jizō-jyu-ou-zou. This group was sculpted early in the Kamakura period, which began in 1185 with the establishment of the Kamakura shōgunate.

The central Jizō figure has some unusual features. He is not holding a staff as usually seen, and his pose is unlike the most common depictions.

Jizō was known in the original Sanskrit as Kṣitigarbha, meaning "Earth Treasury". A fuller form of his name, "Bodhisattva King Kṣitigarbha of the Great Vow", is Daigan Jizō Bosatsu in Japanese.

As a bodhisattva Jizō vowed to instruct all beings in the era from the death of the historical Gautama Buddha until the arrival of Maitreya.

Japanese mythology says that the souls of children who die before their parents are not able to cross the mythical Sanzu River on the way to the afterlife, as they had not had the opportunity to accumulate enough good deeds. They would have to pile stones eternally on the banks of the Sanzu River as penance, but Jizō saves them.

Jizō's iconography typically depicts him as a monk with a halo around his shaved head, carrying a Cintāmaṇi, a wish-fulfilling jewel that lights the darkness, and a shakujo staff to force open the gates of Hell. He is usually standing on a lotus base, symbolizing his release from rebirth.

Here, he's seated and doesn't have his staff. But there's the round halo around his head, within the gold full-body mandorla, and he has the jewel in his left hand.

The ten Kings of the Underworld judge sins and save those in the realm of the dead.

The next group depicts the Three Nyorai.

The three are Kongokai Dainichi Nyorai in the middle, Amida Nyorai at left, and Shaka Nyorai at right. These were sculpted at the end of the Heian period.

The holes in the bases were probably used to store Buddhist scriptures and prayers.

The next niche has The Three Amida Nyorai, the central figures of this cluster. They were sculpted in the late Heian period.

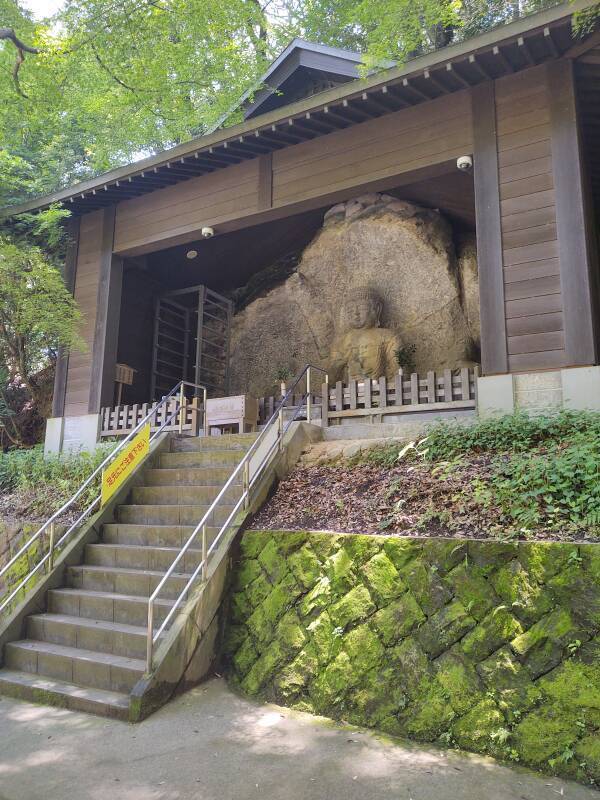

Sannōzan Buddha Group

The path makes a turn around the side valley you have been following, and climbs some steps to a group of three figures now protected by a building constructed around and above them.

Mind the snake.

This group has a central Amida Nyorai figure with a smaller Amida Nyorai attendant on each side. These were sculpted in the late Heian period.

Furuzono-sekibutsu

The central figure of Dainichi Nyorai in this group is regarded by many as the finest stone Buddha statue in Japan.

This group has suffered much damage through the centuries. The head of the central figure had fallen off and was kept on a nearby pedestal. There was an acrimonious debate about whether it should be repaired or not. However, the Ministry of Education made full restoration a requirement for this to be designated as a National Treasure of Japan. So, in 1993 the head was put back in place.

In recent years the replacement of the head has come to be interpreted as "the Buddha didn't get fired", and people now come here to pray that they stay employed.

Because of the damage to the attendant figures, debate remains over the identities of several of them. One interpretation says that on each side there are:

- Two statues of Tathāgata, or Nyorai,

- Two statues of bodhisattvas,

- One statue of Myōō, a wrathful Wisdom King figure, and

- One statue of a Tenbu or celestial figure

The Valley of the Stone Buddhas

There are several homes in the valley, and also farm fields. Very little potential farmland goes unused in Japan.

Some ponds are filled with lotuses during the summer months.

The Well of Beauty

A small well associated with a legend is located partway up the slope overlooking the valley. It's Kesho-no-ido or the Well of Beauty.

The legend says that Princess Tamatsu had dark birthmarks on her face and body. Then she washed her face and body with water from this well, and the birthmarks disappeared and she became a renowned beauty.

One version says that she was the wife of Kogoro the Charcoal Maker. Charcoal production seems to have been a major industry here during past centuries.

Another version says that Tamatsu (or Tamatsu-Hime) was the concubine of a minister in the Imperial capital at Heian-kyō (thus in the period 794–1185 CE). Her flawed beauty meant that they could not marry. She prayed to the god of matchmaking, who appeared to her in a dream and told her to come here and find Kogoro the Charcoal Maker, and have him take her to the well.

People still collect water to wash themselves, in hopes of removing birthmarks, moles, and warts. Dippers and a funnel are provided.

DO NOT INGEST THE WATER.

I returned to Usuki by bus, and saw its castle ruin and associated sites.

Next❯ To Usuki

Other topics in Japan:

This is about the second cluster you reach, confusingly labeled "#1" on some maps.