Tsukiyama Kofun

Tsukiyama Kofun, a Prehistoric Burial Mound

The Japanese archipelago was first settled by Paleolithic

hunters from far eastern Siberia,

starting around 35,000 years ago.

Sea level was much lower and

Hokkaidō was joined to the mainland

and to Honshū.

What we think of as the core of Japanese culture —

a Japonic language,

wet rice agriculture,

and the worship of kami —

started arriving much later, around 950 BCE.

Those new people, the Yayoi,

arrived by boat in northern Kyūshū.

They spread out from there and

displaced the earlier people.

From the middle 3rd century CE to the early 7th century,

the Yayoi built kofun,

a distinctive form of megalithic tomb.

All that happened before any history was recorded in Japan,

and long before any one ruler controlled a significant

fraction of the territory.

Mysteriously prehistoric megalithic tombs,

I'm interested!

And there are some in and around Ōita.

I visited Tsukiyama Kofun

on my first full day there.

It's a short ride by local train to Kōzaki Station

at the edge of the city,

and then a short walk from there.

Google Maps dynamically generates the map when you load this page. Depending on what time it is in Japan, you may see buses by a different route instead of my rail trip.

Start By Train

Guesthouses at Booking.comI was staying at the Hotel 910 in Ōita. I think that business travelers have been their main market. But now I could easily reserve a room there through booking.com. When I arrived, the only foreign guest arriving that day, probably the only foreign guest there through my entire four-night stay, it was easy to match me to the reservation. I could only say "Hello" and "Thank you" in Japanese, and they weren't much further into English, but it worked out easily.

It was only a ten-minute walk to Ōita Station, where I could buy my ticket for the train to Kōzaki Station.

The display was, as usual, a little intimidating when I first looked at it. But look, there's a red box with Ōita showing where I am.

I had researched my trip on Google Maps.

Kōzaki was the sixth station

on the way to Usuki,

which is a big town that would get some foreign

visitors,

and is likely to appear in romanji on a map.

If all else failed, I had KŌZAKI

written on a slip of paper.

I could ask for help and show that.

But there was no need! There was Uzuki in romanji on the blue line below Ōita, and Kōzaki also got a romanji label! The map showed that I needed to buy a ¥ 380 ticket from the machine.

I could always buy a minimal cost ticket for ¥ 210 and then use the Supplemental Payment machine to get out of the station at the far end.

I needed the Nippō Line in the direction of Usuki. Here's my train. It would be 19 kilometers to the sixth stop, Kōzaki.

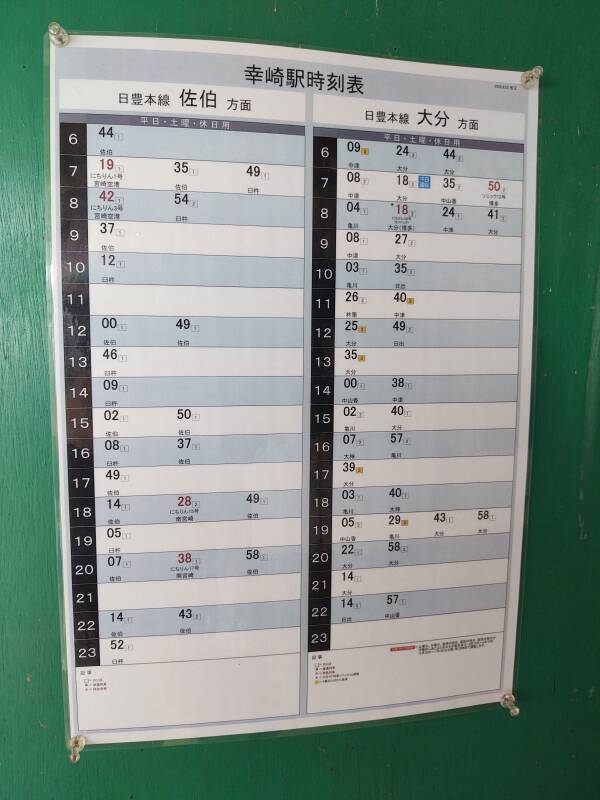

Google Translate for images can tell me that the left column of this schedule posted in Kōzaki Station is for trains toward Saeki, and the right column is toward Ōita.

The trick is to look at the schedule when you arrive. My train pulled out to continue toward Usuki within a minute of stopping. It's a Japanese train so it will be running precisely on schedule. Once I find the departure a minute after my arrival, I know which side of the schedule lists trains continuing to the south. That means that the other column lists trains back to Ōita.

Now I was ready to venture out of Kōzaki Station.

The Rest of the Way on Foot

I had a walk of about 15 minutes past some houses and gardens, and along a highway past two schools.

A shrine, vending machines, a cellphone tower.

There's a cluster of houses near the Kanzaki Hachiman Shrine. I needed to go up the small lane between the houses to the shrine. I would visit it first, and then continue to the kofun.

Kanzaki Hachiman Shrine

My first stop was the Kanzaki Hachiman Shrine. The entry is through a stone torii with a heavy hemp rope with tassels — this is definitely Shintō.

Shintō was largely codified in the early 8th century CE in what are purported to be the first recorded histories in Japan. The Kojiki and Nihon Shoki are largely collections of creation myths and other legends, including how the first Emperor was directly descended from the creator deities. However, they are believed to accurately record some details of monarchs #38–41, who reigned from 668 to 703 CE.

Buddhism had arrived in Japan in 538 CE. Shintō is a pretty thin broth of vaguely defined kami or nature spirits, so it absorbed several details of Buddhism and the animism of the earlier people the Yayoi were displacing.

Hachiman is a divinity of archery and war, a syncretic mix of Shintō and Buddhism. The Shintō side defines him as the divine form of Emperor Ōjin, Emperor #15 ruling 270–310 CE according to legend. Historians think that he might have existed, although significantly later if he did, late 4th to early 5th century.

Farmers and fishermen worshiped Hachiman, or at least tried to appease him for good harvests and catches. Later, the samurai honored Hachiman for his association with archery and warfare.

The legends say that Emperor Kinmei decreed during a certain year of his rule that the deified Emperor Ōjin had first revealed himself as Hachiman in the settlement of Usa, now a town on the rail line north of Ōita. Working through the myths and genealogies and calendars, that pronouncement supposedly happened in 571 CE, about a century and a half before the first historical records.

Hachiman was thus defined as a deified ancestor of the later Emperors. He is the secondary guardian deity of the Imperial Household after the Grand Goddess Amaterasu, said to be the direct ancestor of Jimmu, the first Emperor.

In the 8th century CE, Japanese Buddhism adopted Hachiman as a Shintō kami who could manifest as a Buddhist bodhisattva. Small Shintō shrines to Hachiman were incorporated in Buddhist temples.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 returned the Emperor to national power. It also redefined Shintō, emphasizing the divine ancestry and nature of the Emperor. The first shrine to Hachiman, at Usa, was officially designated as being in the first rank of government-supported shrines in 1871. In the following decades Buddhism was suppressed in order to "purify Shintō" and Japan embarked on an escalating series of wars.

The end of World War II brought an end to what the U.S. had called "State Shintō", which never had been called exactly that. But the point was that the Emperor no longer had absolute power as a god leading a racially superior nation. And, the Hachiman shrine in Usa was no longer especially favored by the national government.

Now Hachiman is the second-most-honored kami in Shintō. About 2,500 shrines are dedicated to Hachiman, who is believed to inhabit all of them simultaneously. Meanwhile, more than 32,000 shrines, one third of the estimated total of 100,000 Shintō shrines in Japan, enshrine Inari Ōkami, the kami of foxes, fertility, agriculture, industry, and general prosperity and success.

This shrine complex is at the base of the kofun.

This slope is the conical section of the kofun.

First, though, I'll look around the Hachiman shrine. The honden of a shrine is the structure where the kami is enshrined or housed.

The white paper zigzags or shide are another Shintō symbol.

The thick vertical rope hangs down from a large rattle. You're expected to shake the rope and its rattle, then clap twice to awaken the kami, the local deity.

Most Japanese people also do the double clap at Buddhist temples, to the exasperation of Buddhist priests.

The honden was pretty austere, as usual.

What's a Kofun?

A kofun is a megalithic tomb covered with an earth mound. Megalith from the Greek μεγάλοσ λίθος, "large stone".

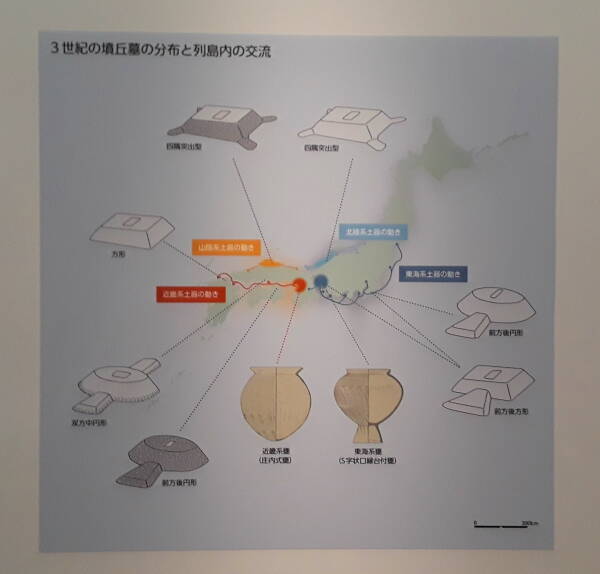

The most common shape of a kofun earthen mound looks like a keyhole when viewed from above. A truncated cone is centered on the tomb. A rectangular or wedge-shaped piece about half the height of the cone extends out, with its wider end away from the cone. This one has that usual keyhole shape. Below is a display in the National Museum in Tōkyō. It shows two pottery designs in light brown, and the range of kofun designs. The most common, like this one, is the dark grey one at lower left.

The Kofun Period of Japanese history is defined as starting around 300 CE, when the first of these burial mounds were built, and lasting until 538 CE when Buddhism arrived from China by way of Korea. The descendants of the Yayoi people continued building kofun into the early 7th century.

Then there was the Asuka Period, which lasted until 710. The dominant leader in central Honshū was based in the Asuka region, about 25 kilometers south of today's Nara.

The Nara Period began in 710 when Empress Genmei established the new capital of Heijō-Kyū, just outside of today's Nara. The ruling clan was gaining power and seeking more. The first purported histories of Japan were written there, Kojiki in 712, and the more detailed Nihon Shoki or Nihongi in 720. They described the creation of the universe and the ruler's descent from the creator gods. Those myths merged with kami worship and whatever remained of east Siberian animism to form Shintō.

The Heian Period began in 794, when Emperor Kammu moved his court about 35 kilometers north from Heijō-Kyū to the new city of Heian-Kyō, which became Kyōto. The Imperial Court remained there until 1878.

Imperial kofunaround Nara

I first saw kofun during my first solo trip to Japan, in 2018. I had planned to go to Nara and then to Kyōto. I read about the kofun around Nara, and visited them.

That area was where the earlier ruling courts had been based. The assumption was that of course many (or most, or all) of those kofun were the tombs of early Emperors.

You might very reasonably object, "But the divine nature of the Emperor is just a myth!" Yes, and that's the most sensitive secret. There's no investigating a purported Imperial kofun.

"Emperor" was an exaggerated title for those clan rulers, as they only ruled over a small region in central Honshū. But they were already using the Chinese terms for "Son of Heaven" and "Heavenly Sovereign", and the ruler was believed to be descended from the gods. All the kofun around Nara were off-limits to any historical or archaeological investigation. Most of them were at least partially surrounded by maintained moats, so you could look at them but you couldn't step onto the ground surrounding them.

IshibutaiKofun

The only exception in the region around Nara was the Ishibutai kofun, south of Asuka. It was believed to be the tomb of Soga no Umako, a powerful clan figure whose death around 626 CE and tomb were mentioned in the Nihon Shoki. The earth mound had been removed, exposing the megalithic tomb, and archaeology carried out.

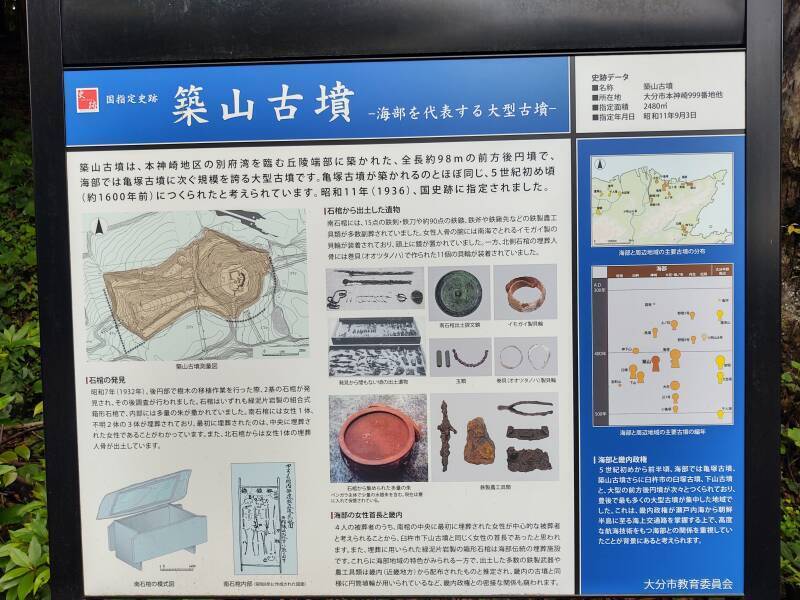

The Tsukiyama Kofun

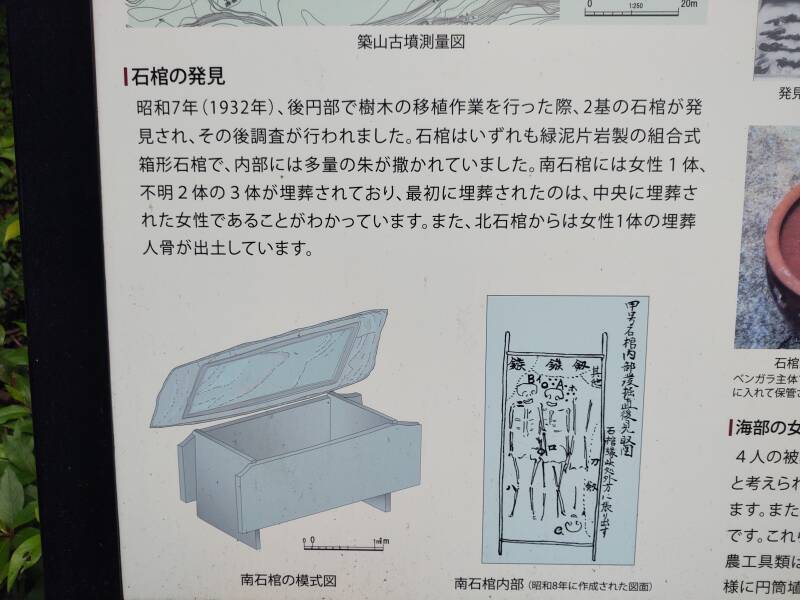

The Tsukiyama kofun, however, is far from any speculative Emperor burials. Science is allowed. Archaeologists excavated here in 1932, and again in 1966. A sign next to one of the shrine structures had some explanation of what they found and what you see today. It's at the base of the conical part.

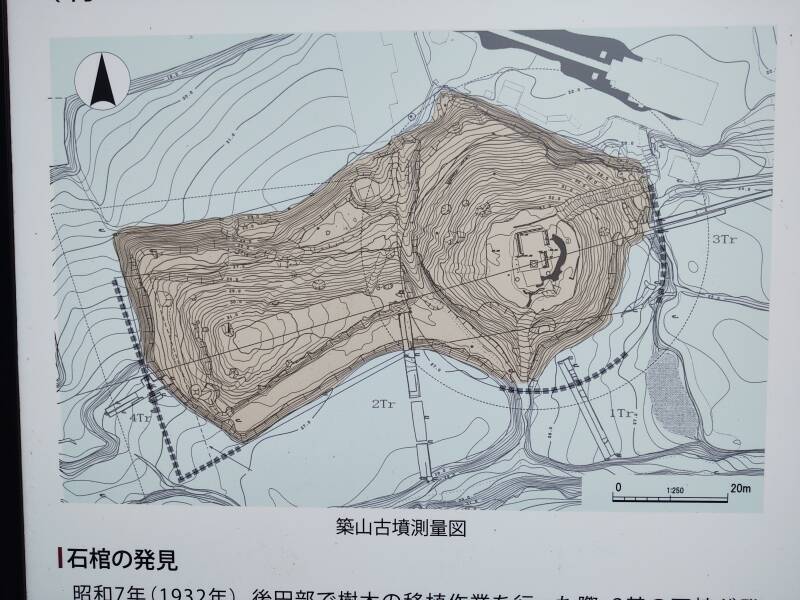

The text above the topographic map says, according to Google Translate for images:

Tsukiyama Tumulus is a keyhole-shaped tumulus with a total length of approximately 98 meters that was built on the edge of a hill overlooking Beppu Bay in the Honkanzaki area, and is the second largest tumulus in the Kai area after Kamezuka Tumulus. It is thought to have been built around the beginning of the 5th century (approximately 1,600 years ago), around the same time that Kamezuka Tumulus was built. In 1936, it was designated as a national historic site.

The round conical section is about 42 meters in diameter, rising 14 meters above the surrounding terrain. The wedge-shaped section extends out about 50 meters, 40 meters wide and 6 meters high at the far end.

The burials discovered in 1932 were at the center of the top of the cone.

There are some groups of kofun all aligned the same direction. However, there is no general pattern to the alignment of individual kofun or groups or them.

Maps out in public in Japan are usually aligned so the top of the map is the direction in which you're facing as you look at the map. However, this map is from the archaeological study and the black arrowhead points north. The main axis of this kofun is about 70–250°, about 20° off east–west.

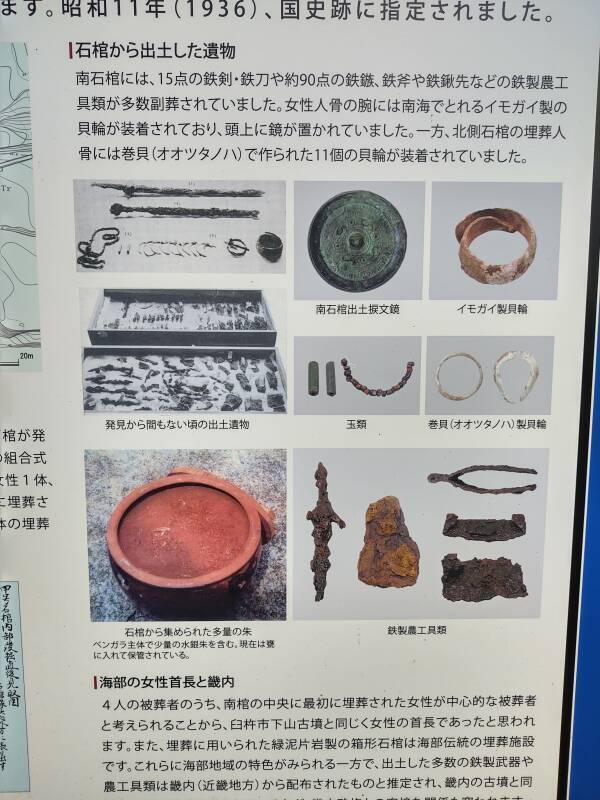

The graves had never been robbed, and archaeologists found that they were some of the most opulent burials in the region.

The two box-shaped sarcophagi were made of slabs of locally sourced chlorite schist, typical for this region. The northern sarcophagus contained the remains of a woman who had a shellfish bracelet on her right arm.

The southern sarcophagus contained the remains of three bodies. The first one to have been buried was a woman, the other two were of indeterminate sex. Those three bodies were accompanied by iron swords and daggers and agricultural tools, a bronze mirror, rings made from conch shells, glass beads, and remains of linen and silk fabric. The grave goods indicate that the graves date from the first half of the 5th century CE.

A total of 34 kilograms of vermilion pigment, made from the powdered mineral cinnabar, was spread through both sarcophagi. Archaeologists have found vermilion dating back to 8,000–7,000 BCE at the Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük in today's Turkey. The Yangshao culture in China in 5,000–4,000 BCE used cinnabar to paint ceramics, cover the walls and floors of rooms, and in ritual ceremonies.

Cinnabar or vermilion is a brilliant red to orange pigment. Unfortunately, cinnabar is powdered mercury sulfide, HgS, a deadly poison. You wouldn't want to live in a vermilion-painted room, or take part with ceremonies in which cinnabar dust is spread through the air. It was a very expensive material given the danger of its production. First, you must dig a mine, always a hazardous operation. Then, workers must grind the poisonous ore into a fine powder.

A Smithsonian article described a site from 2900–2650 BCE in today's Spain where priestesses ingested cinnabar powder, putting them into a trance with tremors and delirium. As the article says, they would have experienced memory lapses, fatigue, tremors, and possible kidney failure. It describes other dangerous cinnabar uses through history and in today's traditional and alternative medicine. See the article in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory for details of the Spanish site.

The cinnabar found in this tomb served as a grave good and decoration. I didn't see anything about the bones having been tested for signs of similar heavy-metal shamanism. That would be something for further investigation.

The two women, especially the one buried by herself in the northern sarcophagus, are speculated to have been priestesses or shamans. The Ōita city web site says, "It is one of the representative tombs of Amabe where a female chieftain was buried [...] There is a theory that the women may be 'Sokusuihi Onna' who are worshiped as local deities."

Another city web page says "Since the area was later designated as Kaifu District, it is thought that the people living there were a technical group that made a living by working at sea and, with their excellent navigational skills, played an important part in the Yamato monarchy. The person buried in the center is thought to have been the female chief."

The presence of female chiefs or priestesses with some connection to the later Yamato monarchy has led to further speculation in the Yamataikoku debate.

Yamatai or Yamatai-koku is the Sino-Japanese name of an ancient country in Japan. Chinese records describe Yamatai as existing during the late Yayoi Period, from about 1,000 BCE to 300 CE, when the people began to build the massive kofun memorial tombs.

Japanese linguists and historians continue to debate where Yamatai was located, and whether or how it was related to the later Yamato rulers who eventually assumed the title of Emperor. The clan chiefs of Yamato competed with rulers of surrounding local to regional powers. They gained wider control in the sixth century CE and eventually assumed the title of Emperor.

Was Yamatai the predecessor of Yamato, and if so, where was it based? Maybe so, and maybe around here. Absurd and fanciful theories abound regarding the location of Yamatai. The current debate over plausible locations of Yamatai focus on northern Kyūshū, where this kofun is located, and the Yamato Province near today's Nara.

The text below the topographic map says, according to Google Translate for images:

In 1932, two sarcophagi were discovered during tree transplantation work in the rear circle, and an investigation was subsequently conducted. All of the sarcophagi were box-shaped sarcophagi made of chlorite schist, and the interior was sprinkled with a large amount of vermilion. There are three bodies buried in the south sarcophagus, one female and two unknown bodies, and it is known that the female buried in the center was the first to be buried. In addition, the human remains of a female burial were excavated from the north sarcophagus.

The text at the top of the following section says, according to Google Translate for images:

Artifacts excavated from the sarcophagus

The southern sarcophagus contained 15 iron swords,

approximately 90 iron arrowheads,

and many iron agricultural tools

such as iron axes and hoe tips.

A shell ring made of a cone shell from the southern seas

was attached to the female human skeleton's arm,

and a mirror was placed above her head.

On the other hand, 11 shell rings made from

conch shells (Otsutanoha) were attached to

the bones of the people buried in the north sarcophagus.

At the bottom:

Female chiefs of Kaifu and Kinai

Of the four burials, the woman who was buried first

in the center of the south coffin

is thought to be the main burial victim,

so it is thought that she was the head of the burial mound,

similar to the Shimoyama Tumulus in Usuki City.

The box-shaped sarcophagus made of chlorite schist

used for burial is a traditional burial facility in Kaifu.

While these exhibit the characteristics of the Kaifu region,

many of the excavated iron weapons and agricultural tools

are presumed to have been distributed from the Kinai region

(Kinki region), and are the same as the tombs

in the Kinai region.

The red pot is filled with vermilion.

The map shows the major burial mounds in this area. This one is the furthest to the east along the north coast.

The chart of position versus date shows this one constructed shortly after 400 CE. The larger Kamezuka kofun, which I would see later that same day, toward the center of the city, was built a little earlier, but still after 400 CE.

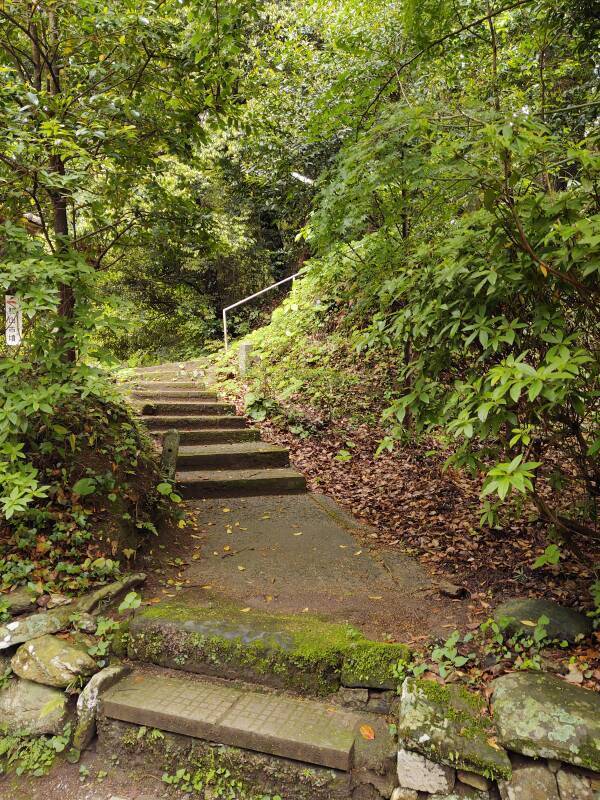

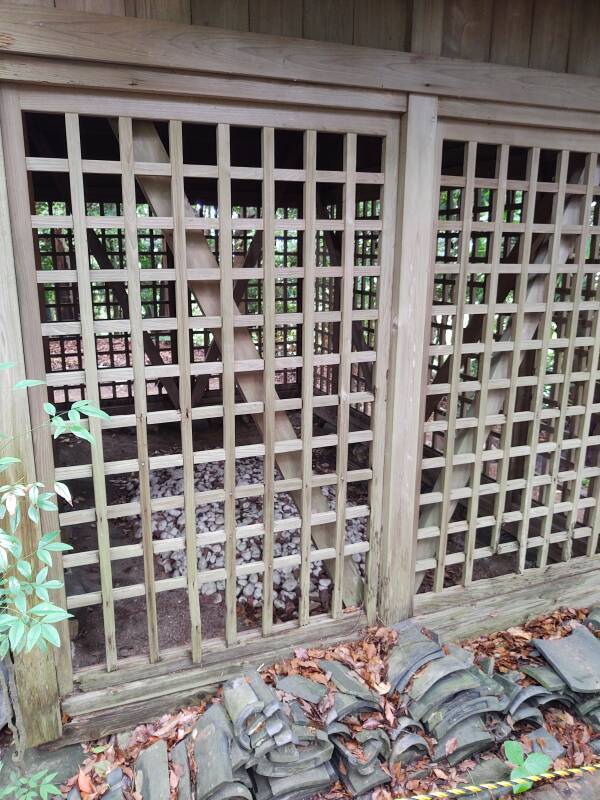

You can see a structure at the top of the kofun.

A staircase goes up the hill from the shrine.

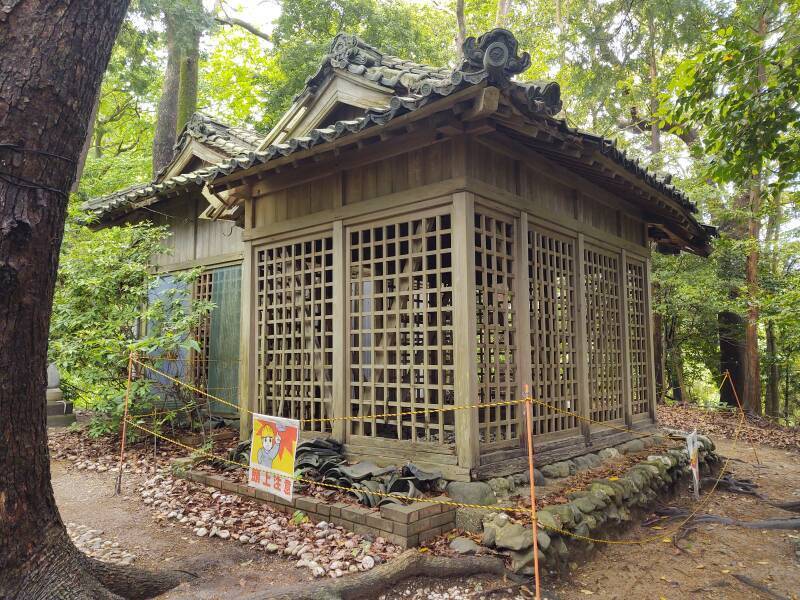

A pair of small modern structures stand on the peak, sheltering the grave sites.

They are configured as Shintō shrines with hemp rope and rattle, and hanging shide.

Above, you see ema or prayer plaques that visitors have inscribed and hung on the exterior.

Prayers to whom? Depending on which side you take in the Yamata-ikoku debate, this might be the grave of a local leader with some connection to predecessors of Imperial rule. But then what would that mean?

Shintō isn't a religion as most languages define that term. Today, outside the Shintō priesthood, it's a distinctively Japanese cultural activity. At best, shaking the rattle and clapping and hanging an ema are like the Altar to an Unknown God that the apostle Paul saw in Athens during the mid-1st century CE. Buy an ema and write a wish on it, just in case.

The shrine structures at the peak of the kofun enclose small areas covered with small white stones. This is fukiishi. Small rounded stones were collected from riverbeds and placed as an external layer over the entire kofun. It's thought that the outer stone layer served two purposes — to protect the earthen structure from erosion, and to make it visually striking. Here you can see the lid of one sarcophagus, I don't think it would have been exposed originally, but I'm no kofun expert.

The fukiishi covering and the haniwa clay figures and cylinders placed around the peak fell out of use soon after this kofun was built. Kofun continued to be built into the early 7th century CE. But by the early 6th century the fukiishi and haniwa were seldom added.

Trees have grown up over the kofun, but from the peak of the cone you can see the wedged-shaped section tapering out to the east.

Around the Shrine and Kofun

People in the neighborhood of the kofun maintain gardens. Most suitable plots of land in Japan are used for agriculture, because so much of the archipelago is rugged mountains.

A bridge on a small road depicts the nearby kofun.

A sign warned of the raccoon invasion. Raccoons, as depicted in various media and observed from a distance, are kawaii, the term for extreme cuteness. Raccoons are native to North America, they aren't naturally found in Japan. A popular anime series in 1977 led to about 1,500 raccoons being imported to Japan as pets.

Raccoons are highly intelligent, sometimes aggressive, and largely uncontrollable. They're far less kawaii when you're living in close quarters with one. Some escaped, and others were intentionally released into the wild. By 2008 raccoons had been spotted in all 47 prefectures of Japan, where they cause a great deal of agricultural damage and ecological disruption. They can carry rabies and a roundworm parasite that causes progressive and eventually fatal neurological damage in humans.

Now the Ōita Prefecture government urges citizens to report raccoons, but not the native badger, raccoon dog, or palm civet. That way the government staff can, um, escort the raccoons to a pleasant life in a distant forest. Or something like that.

I returned to the highway and started walking back toward Ōita. I passed a bus stop which verified that the kofun is locally known as Tsukiyama and not "Chikuyama" as Google Maps insists.

Some fields were ready for harvest.

I continued east toward Kamezuka kofun with stops for more interesting sites along the way.

Next❯ To the Kamezuka kofun

Other topics in Japan:

Google Maps insists that this is the Chikuyama Tumulus. However, local signs call it Tsukiyama. So does Japan's Cultural Heritage Online web site.