Usuki

The Ancient Feudal Town of Usuki

I had been staying in Ōita as I explored the area, and I had taken a local train a short distance southeast to Usuki to see the Stone Buddhas. Now I would have a brief look around Usuki before returning to Ōita.

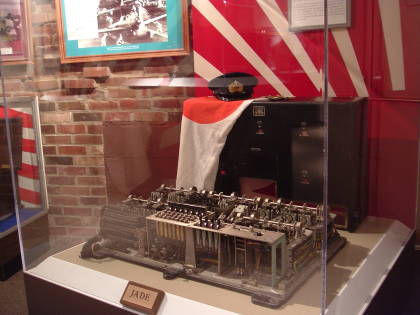

Small portion of 1:500,000 aviation chart TPC G-11D, from the Perry Castañeda Library Map Collection

Into Usuki On The Bus

I had walked from the Kita-Usuki train station to the Stone Buddhas. It was a pleasant walk of about 4.5 kilometers.

But when I was ready to head back toward Usuki, I saw on the schedule posted by the ticket office that a bus to Usuki would stop there in just a few minutes. I decided to ride back.

To ride a bus in Japan, enter by the rear door and then be sure to take a ticket from the machine just inside the door. That's the sort of yellow box with the red-on-white label in the below picture.

Yes, that's a smart card touch reader with the blue-and-white label at upper left. I had a Pasmo card, and it and the Suica card are usually interchangeable. But I was all the way down in Kyūshū, and this might be a zone with an entirely different card system. I needed to hop on the bus and quickly get my fare set up, and this was my first local bus ride in Kyūshū, so I got a ticket.

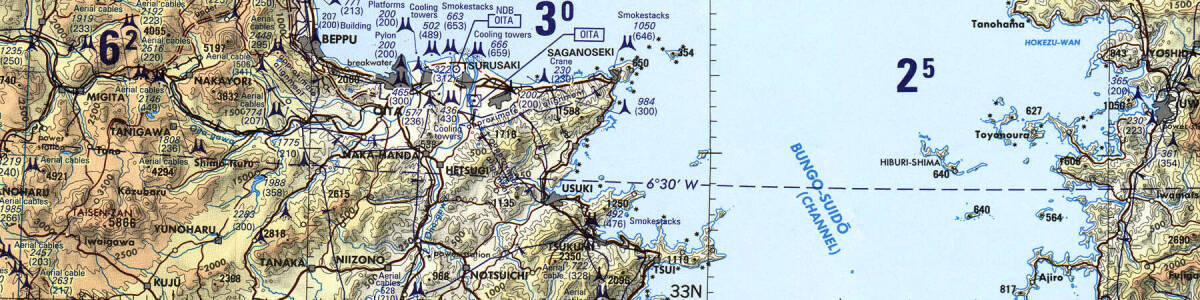

It didn't look very exciting, just purple-pink 29 ba-n, but you have to get a ticket. The machine custom prints it based on where the bus was when you boarded.

Sitting down, I could see the display panel above the windshield showing fares if you got off at the next stop based on where you boarded. To get off, I would give my ticket to the driver and the cashbox would display how much I owed.

I got out of the bus as we neared the castle. That happened to be close to the police station with the typically retro-futuristic police cars. Japanese police cars look like vehicles out of some puppet-based British science fiction from the 1960s.

Usuki Castle

I walked down to the major intersection, crossed the street, and went up a large steel spiral that took me up the equivalent of two to three stories, where a ramp crossed over a traffic lane, sloping up to the castle.

Crossing that ramp and climbing futher up to the restored castle grounds, I was soon the equivalent of six or seven stories above ground. In the distance to the northwest I could see the Nipponzan-Myōhōji-Daisanga Stupa.

Nipponzan-Myōhōji-Daisanga or just Nipponzan-Myōhōji is a new religious movement founded in 1917, branching off Nichiren Buddhism. They revere the Lotus Sutra, and their main practice is to chant Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō and promote peace and non-violence through erecting peace stupas, aka pagodas.

Looking to the northeast, I could see out over the harbor and the shipyard, past a small island into the Bungo Strait that separates the major islands of Kyūshū and Shikoku, connecting the Inland Sea to the Pacific Ocean. Ship-building is the major industry in Usuki, brewing soy sauce and miso is number two.

Usuki Castle was built around 1555–1565 by Ōtomo Sōrin, the local daimyō or feudal lord. He was married to Lady Nata, who was a high priestess of Usa Jingū, a major Shintō shrine a short distance to the north. She actively resisted the Jesuit mission to Japan in general, and the spread of Christianity in Kyūshū in particular.

At that time, this castle was on an isolated rock in the sea. The island had steep rock faces all around, making it a natural fortress. Land was filled in over the centuries and now the castle is about 800 meters from the inner harbor and shipyard. And, modern concrete retaining walls keep the earth in place.

1530: Ōtomo Sōrin is born.

1543: Portuguese traders land on Tanegashima, introducing matchlock firearms to Japan.

1545: Ōtomo marries Lady Nata.

1549: Francis Xavier, the first Jesuit missionary to Japan, first went ashore at Kagoshima.

1551: Ōtomo meets personally with Francis Xavier.

1550s: Ōtomo sends political delegations to Goa, the Portuguese colony in India.

1562: Ōtomo adopts the Buddhist monastic name Sanbisai Sōin, but remains best known as Ōtomo Sōrin.

1570s: Lady Nata is one of the main reasons for the small and slow spread of Christianity in Bungo province.

1578: Ōtomo divorces Lady Nata at the urging of the Jesuits. They baptize him under the baptismal name Francisco. They then urge him to destroy Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines, and force some of his subjects to submit to Christian baptism. His support of the Jesuits seems to have been much more political than religious.

1582: Ōtomo sends the "Tenshō embassy" group to Madrid and onward to Rome. They spent nine months visiting Portuguese territories along the way — Macau, Kochi, Madagascar, and Goa. Then they sailed around Africa to Lisbon, and continued on. They met with King Philip II of Spain and Portugal; Francesco I de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany; and both Pope Gregory XIII and his successor Pope Sixtus V.

1582: Lady Nata dies.

1587: Ōtomo dies.

1590: The Tenshō embassy group returns to Japan, and its four main members were ordained as the first Japanese Jesuit priests.

1600: The Dutch ship De Liefde is stranded on the coast near today's Usuki, where Portuguese Jesuit missionary priests claimed that it was a pirate vessel and all crew should be executed. Two of the nine survivors settled in Japan. One of them, the ship's English pilot William Adams, became a key advisor to the shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu and directed the construction of Japan's first western-style ships. James Clavell's best-selling novel Shōgun is based on Adams' life with the names changed.

1603: The Tokugawa shōgunate took power, and began suppressing Christianity after 1610, more so after the Seclusion Laws of the 1630s.

The castle was extended and modified, and remained the political, economic, and cultural center of what then was Bungo province until the Meiji Restoration. The main keep and many other structures were demolished in 1886.

Now the large flat area at the top is a nice park, very popular when the cherry blossoms appear in the spring.

This large high point is the city's tsunami evacuation point. The Nankai Trough is a subduction zone on the sea floor running roughly parallel to the Home Islands of Japan, to their southeast. Devastating megathrust earthquakes occur there about every 90–200 years, often in pairs, and associated with tsunami. Recent ones were in 1707, two in 1854, and then in 1944 and 1946. A Nankai Trough megathrust event is expected to produce a tsunami that would still be at least six meters high when it reaches Usuki.

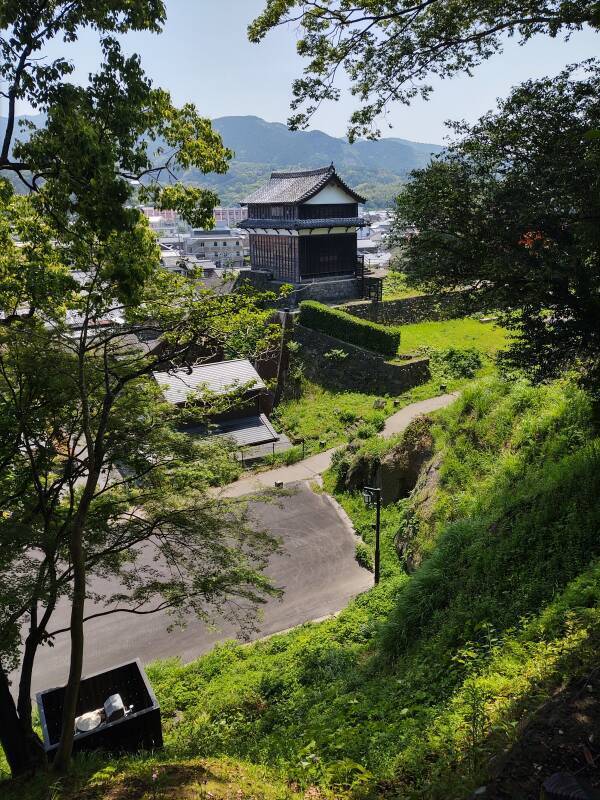

Just a little of the upper walls and turrets remain.

There are views out over town on both sides. Homes are built right up against the base of the former island.

A restored three-story tower is on an outcropping below the highest part. Called Utono-guchi, it was most recently reconstructed in 1854. Earlier versions had stood there at least since the early 1600s.

A long sequence of vermilion torii leads up from town to the Utono Inari Shrine. The area was once the rear entrance to the castle. It served as an emergency exit through which feudal lord and his family could quickly reach a boat and escape by sea.

The Utono Inari shrine is on this outcropping just a little above Utono-guchi.

Fushimi Inari-taisha shrine in KyōtoIt enshrines, or is inhabited by, Inari, the most popular of the Shintō kami. Out of the roughly 80,000 or more Shintō shrines, at least 32,000 are dedicated to Inari. Japan's main Inari shrine is Fushimi Inari-taisha shrine in Kyōto.

Inari is the deity of rice and agriculture in general, tea and sake, fertility, household well-being, and business and personal prosperity.

The deity or kami Inari is associated with foxes, who act as Inari's messengers. Foxes are typically depicted as guardians of the shrine like the ones you can see here. They might be regular foxes, or maybe they're kitsuni, paranormal foxes. The guardians at the shrine usually appear in pairs, one male and one female, and one or both may hold a symbolic item under a front paw or in their mouth.

The myth says that Inari came to Japan at the time of its creation. She took the form of a goddess and descended from heaven riding on a white fox and carrying sheaves of some cereal that grew in swamps before rice was brought to Japan.

Each torii marks a passage into a more sacred space. It's the same gateway concept across almost all religious architecture. Here, we're looking down from the shrine area, so we're looking out from the most sacred area.

A yellow torii stands over one end of the main shopping district. Beyond, a street leads to the shipyard.

The pole holding up one of the old-style lanterns also holds a tsunami evacuation sign. It points toward the stairs leading up past the three-story Utono-guchi tower and through the torii to the top of Usuki Castle.

Streets in Japan are typically lined by water drainage channels formed from rectangular concrete slabs. Three slabs form the bottom and two sides. The resulting channel is capped with slabs whose notches allow the water to drain into the channel and be carried away. The result is a water gutter that drains very efficiently, and a smooth surface from the sidewalk into the street.

I had just a short wait at Usuki Station for a train returning to Ōita.

Late Lunch or Early Dinner

I had gotten an early start, and I was back in Ōita by mid-afternoon. I hadn't had lunch, so I went to a ramen shop near my hotel.

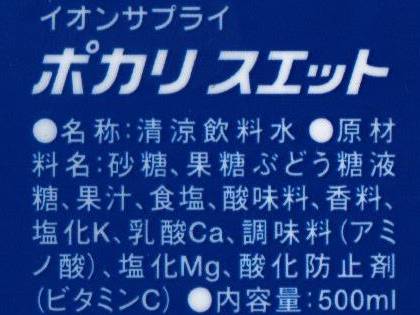

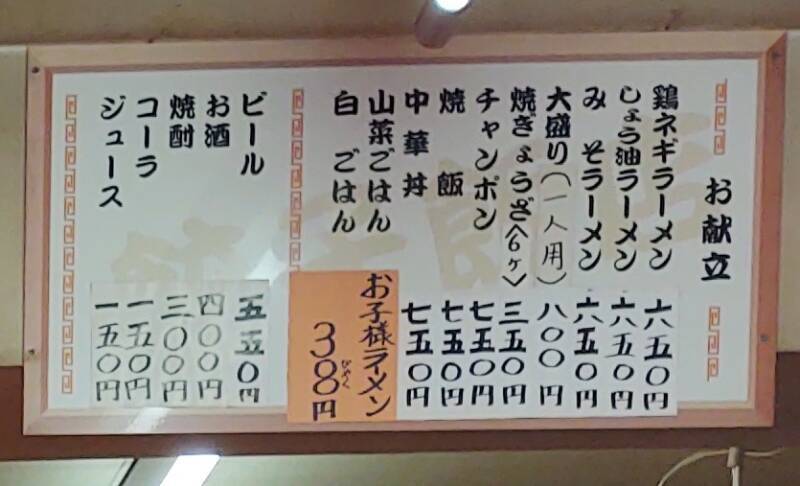

It was not a tourist stop. The menu was on the wall, entirely in Japanese with Chinese numerals.

The sign outside had clearly said that they have ラーメン or ramen. Inside, the menu listed the types of ramen, above at far right for ¥650 each. It also showed that drinks, at left, included ジュース and コーラ or jusu and kora for ¥150, kanji mysteries for ¥300 and 400, and ビール or biru for ¥550.

It worked out well!

I stayed two more nights in Ōita, making a day trip to Mount Aso before traveling by express train and Shinkansen to Kyōto.

Next❯

To Mount Aso

Later❯

To Kyōto

Other topics in Japan: