Bob's Blog

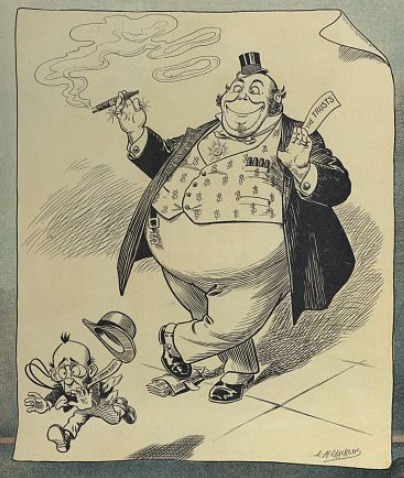

Cybersecurity Certifications are Unfair, and are Far Less Meaningful Than They Claim To Be

I understand the need for cybersecurity certifications,

or at least their utility.

They have their uses.

Or at least they could if they weren't so focused

on gaining money and influence for the organizations

that operate them.

Meanwhile, many people in the IT industry

repeat the ridiculous claims of the certification industry.

Have they really "drunk the Kool-Aid" and become convinced

of the supposed significance?

Or do they just feel obligated to echo those claims?

The certification industry has power over

many people's careers through its exams

in which questions are intentionally ambiguous,

often terribly outdated,

and for which you frequently must select an incorrect choice

to be counted "correct".

All of that is within an exam environment designed for

stress and confusion.

The IT field is not that difficult.

But to spin up an appearance of relevance and value,

the certification industry artificially inflates the

difficulty of their exams.

If the topic isn't difficult enough,

they can resort to psychological pressure

and linguistic trickery.

Or, more simply, require the test-takers to memorize

specific incorrect and outdated "answers".

The real victims here, the people being tested,

must pass these faulty exams to obtain or keep their jobs.

No one in their right mind would put up with this

nonsense voluntarily.

My Background

My meaningful background is that I have a B.S., Master's, and Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering from Purdue University. As far as I'm concerned, these cybersecurity industry certifications are pretty trivial. But, having them in order to teach test-prep classes has brought me flexibly scheduled and financially attractive teaching work. Teaching has been pretty rewarding for providing the feeling that I was helping people through a difficult task. Now, as for the certification nonsense:

I have three cybersecurity certifications from two organizations — Security+ from CompTIA, and CISSP and CCSP from (ISC)2, all of that for purely mercenary reasons.

I was teaching classes for a training company when, in 2003, they announced that they had won a contract to provide training for the NSA, the U.S. National Security Agency. The NSA had said that any instructor presenting a technical course to them, regardless of the specific topic, had to hold the CISSP certification.

The training company wouldn't reimburse an instructor for whatever it cost to prepare and pass the exam, but if you already had the certification, or managed to get it, you were certain to get several weeks of teaching work.

The announcement was soon followed by further requests. Apparently they had very few instructors with the CISSP, and they had heard nothing from any instructors thinking of trying to get it.

I looked into it, and it seemed pretty straightforward. I ordered a book through the local book store, one of a series of test-prep books put out by Mike Myers. No, not that guy, but someone who had organized a series of well-regarded books in the early 2000s.

The book described the topics of cybersecurity in a very readable form, with practice quizzes at the end of each section, and two or three overall practice exams at the end. Plus, you could access further on-line exams by answering some question showing that you had access to the book — "What is the first word at the top of page 74?" or similar.

I was satisfied with the book, because I kept my expectations realistic. There's a very limited market for such a book. This isn't a well-written presentation of an interesting story, like a novel by Stephen King or Margaret Atwood. You would only buy a book like this if you worked within a particular niche within a particular industry. It will get some, but not stellar, technical editing.

Even given that expectation, I was surprised by the number of technical errors I saw, things stated as fact that simply weren't true. Compared to the O'Reilly company's IT books, this seemed sloppy. However, O'Reilly had a larger market and thus a larger budget for technical editing. Many people need to know how to do things with computers and networking, but only some of them need to pass an exam about the topic.

I got ready, and the next exam opportunity was in Chicago on a Saturday — at the time the exam was offered every month or two. The exam was actually outside the city, in a large meeting room at a hotel near O'Hare Airport. I took Amtrak to Chicago, stayed overnight at a hostel, and took the CTA out toward the airport early Saturday morning.

I found myself in a large room with about 200 people. Most of them had been at the hotel since the previous Sunday, attending a "boot camp" course that ran Monday through Friday from very early each morning up into the evening.

You can get people to sit in a meeting room for ten hours a day, and you can even keep some of them awake through much of that. But if you understand anything at all about how adult humans learn things, you know that there's no way you can really teach them things for more than half of that time at best.

Many of the people administering the exam were doing volunteer labor, and more on that in a bit. They told us many procedural details about the exam, including that there was a tiny chance that someone might notice a minor wording error in one of the exam questions. They seemed to expect the probability of such an event to be similar to that of a major earthquake striking during the exam. But if such an unlikely thing happened, we should raise our hand and ask for a special form on which we could report this startling event.

The exam started, and I began to spot errors. Not just subtle errors, but glaring preposterous errors. Here's one I can't forget:

In an IP datagram header, where "IP" of course stands for

Internet Packet, what is the purpose of the TTL field?

A: Authenticate the sending host

B: Prevent routing loops

C: Identify the destination

D: Advertise reachability

None of the answers are really correct. The best answer is, of course, B. It's the one closest to being correct. You can't prevent a routing loop, but with the TTL or Time To Live field counting down at each router hop, it limits the harm of a routing loop. Meanwhile the other three choices have nothing to do with TTL.

However, part of the question that purports to be a statement of fact is wrong. "IP" stands for "Internet Protocol", while "Internet Packet" is simply wrong.

I raised my hand and asked for one of the error-reporting forms. After three cycles of coming across nonsense like this every few questions, and raising my hand each time to get another form, I realized what was going on. I had been doing some technical editing work over the past few years. This sort of erroneous nonsense caught my attention and distracted me. This was exactly what (ISC)2, the certification organization, was hoping for. Asking for and writing on forms, doing volunteer technical editing work for them, that would waste a lot of my limited time allowed for the exam. It would also distract me from the task of analyzing their intentionally poor quality exam content to select the least-wrong or least-bad response, whatever fictional or slightly wrong response they wanted me to select as "correct".

My biggest complaint with the test-prep book I had used, and with every other IT certification test-prep book I have since encountered, is that they don't come right out and say that certification exams are of such horrible quality. I prefer to think that the Mike Myers book was intentionally modeling the faulty nature of the exam content to better prepare the reader for the actual questions. But then it neglected to explain what was going on.

And More Certifications...

I passed the exam and did, in fact, get many weeks of teaching work from that. I thought that the CISSP exam was pretty silly, and my regard for the NSA had dropped significantly, but it worked out well for me.

There was, of course, complicated nomenclature for this complicated multi-track and multi-level program, DoD Directive 8570. That was eventually updated to DoD Directive 8140, but even the Department of Defense still refers to the program as "8570" because everyone else does. Yes, 8140 replaced 8570, the smaller number is the newer directive.

By 2005 the U.S. Department of Defence, hence "DoD", had decided that everyone working on DoD systems or working with DoD data would need some "industry standard" cybersecurity certification. The simple version of this was that Security+ from CompTIA would be the entry-level certification, and CISSP would be required for people who commanded or supervised the entry-level people. Like many tasks, such as designing and building aircraft, the DoD knows roughly what it wants but relies on private industry to carry it out.

The training company saw that there was a lucrative opportunity here, because DoD personnel and also many of the staff at contractors and other support corporations would need to pass this exam. To get their test-prep course up and running quickly, they announced that they would reimburse instructors for the cost of the exam itself. What's more, since they very reasonably require any instructor to first sit in on a run of a course before teaching it, they would fly us to a course event and pay for our hotel and per diem.

And so, in October 2005 I passed the Security+ exam. I thought that the Security+ exam was relevant to the real world and was a far better measurement of useful knowledge. And, the exam wasn't the dumpster fire of horrible content quality that I had encountered in the CISSP exam. At the time the Security+ exam had 100 multiple-choice questions, some of which asked you to select two choices. My score was 98.75%, meaning that getting just one correct on a "pick two" question must have been worth 75% of that question. And, the fact that I missed just one question plus half of another supports my view that this field is not terribly difficult.

My CISSP certification brought me many weeks of teaching networking protocols, the UNIX/Linux command-line environment, and an introductory information security course that, to my surprise, many NSA staffers desperately needed. Security+ brought many more weeks of teaching its five-day test-prep course. It had so much material to cover that it ran for an additional hour each day, so the one-week course yielded 5 and 5/8 days' pay.

By 2018 the NSA contract was long over. Also, the industry was becoming much less interested in training to learn how to do things. The market was becoming more and more focused on just passing the certification exams. So, when the training company started running a test-prep course for CCSP, the (ISC)2 Certified Cloud Security Professional, I bought a book, read it and did its practice exams, and passed the CCSP in November 2018. That led to several more teaching events for about a year.

What's Their Goal?

What are the certification organizations trying to accomplish?

"Money and power" is an awfully glib answer. But what else could it possibly be? There's a lot of money to be made, and they suddenly gained quite a bit of control.

These organizations aren't educational institutions or industry technical experts. But they have become gatekeepers, especially for the U.S. DoD and its contractors. They're securely entrenched in their positions. The government's shift to different certification providers would be complicated and confusing, so that won't happen.

(ISC)2 has gradually taken control of the test-prep training industry as far as their exams are concerned. They have pestered training companies with legalistic claims that preparing people to study and pass their exams was a violation of their intellectual property rights. You could teach test-prep courses, if you only use (ISC)2 material. And by the way, that material cost $800 per student in 2020, a cost that the training company must either absorb or pass along to the student. In 2021-2022 that situation got even worse, as described below.

Almost every test-prep class I've taught has had at least one unhappy military student saying something similar to this:

"The military promised me that they could train me in the Information Technology field. But I can't touch one of their computers without this certificate. How am I to get this with no way to pick up the needed expertise?"

And, there would be at least one unhappy student from a contracting company saying something similar to this:

"I've been working for this company for several years now, but they suddenly told me that I can't keep my current position without this certificate. I'm not a system administrator, or a network engineer, or a programmer. I've never taken a Computer Science class. All I ever do with a computer is read and send email. How am I supposed to pass this exam?"

"But They're Non-Profit Organizations, Right?"

In 2023 the exams cost

$370 or €334 or £219 for Security+,

$599 or €555 or £479 for CCSP,

and $749 or €650 or £560 for CISSP.

Maintaining a certification then costs an additional

$50/year for Security+

and $125/year for all (ISC)2 certifications.

Yes, a certification company may file their taxes

in a way that makes them a non-profit organization.

But that doesn't mean that they don't make a lot of money.

The U.S. National Football League was a

non-profit organization exempt from paying taxes

from 1942 to 2015.

U.S. Major League Baseball was tax exempt until 2007.

Meanwhile those organizations were bringing in billions of

dollars and paying many multi-million dollar salaries.

Yes, but that doesn't really mean anything.

You pay a lot of money to do one of these exams. Then they bill you from $50 to $125 each year to maintain your record in their database. Yes, they keep track of whether you have completed the annual requirement of continuing education, but of course you have to do all the data entry for those records. And, at least once a week you receive email telling you how you could pay them to attend one of their courses for continuing education credit.

The organization's work, including occasional audits of your continuing-ed claims and maintaining the exam question pools, is mostly done by volunteers who are "paid" in continuing education credit.

"But These Certifications, Especially CISSP, are Elite and Meaningful, Right?"

If you're very easily impressed, sure.

I have been surprised by the people who otherwise seem sharp but then quote the organizations' claims, especially the ludicrous ones of (ISC)2.

(ISC)2 released a new version of the CISSP "training material" in April 2021. They ran an on-line presentation for instructors that they had approved to teach their material. They told us that their course material now intentionally does not prepare students for the exam. It seemed to me that their new course would be a nice broad-coverage course on cybersecurity. However, it clearly would not be helpful for preparing for the exam itself.

Let's review what they have done:

- Use legal threats to coerce everyone to use their course material.

- Ensure that their course material is not helpful to someone preparing to pass the eam.

I immediately told the training company I teach for that I was no longer willing to teach that course title. In July 2022 (ISC)2 made the same change to their CCSP material, and I immediately asked to be taken off that course as well.

I can't imagine that more than maybe 5% of course attendees are happy to hear that this course with a specific certification exam in its title has very little to do with helping them to prepare to pass that exam. And by the way, there is no helpful course available. I don't need a week of grief every time I teach a course.

In both those presentations of "new and improved" material, full-time staff of (ISC)2 stated, in all seriousness, that they believe that passing their exam is equivalent to graduating from medical or law school and then passing the relevant board exams. That's utter nonsense. But they said it very seriously, and the Zoom screen showed them and several other Kool-Aid-drinkers nodding in agreement.

But if you manage to pass one of these exams, despite all the intentionally added obstacles, doesn't that mean something? Hah.

CompTIA has a CASP certification described as an advanced or second-level Security+. It's for people who passed Security+ a year or two ago, have continued to work in ever-more-advanced roles in cybersecurity, and are ready for an elite certification. Or so the story goes.

I was teaching some non-test-prep class at the training company's facility one week. Another instructor I know was presenting a CASP test-prep course in another room. I was talking to her during a lunch break, and she said that one of her students had a very specific question that she couldn't answer but maybe I could. It was something about an open-source tool for some task.

The student told me what she was looking for,

and I told her that while I knew there is such a tool,

I haven't used it myself and I wasn't confident that

I was remembering the correct name.

But no problem, I know that I do have its name and a short

description, and probably a link to its web site,

on a page at my web site.

She asked me how to find my web site,

and I told her that I could tell her the specific page.

It was:

https://cromwell-intl.com/open-source/

So, I started reciting:

"H-T-T-P-S, colon slash-slash, ..."

She interrupted me:

"Wait, wait, are those regular slashes or are they

backslashes?"

I was speechless.

Someone attending an IT course,

allegedly an advanced one,

who doesn't know whether you use

"/"

or

"\"

in a URL?

I knew that I could not predict what

anyone asking such a question

would think was a "regular slash" versus a "backslash".

So, I used my usual explanation that should be safe:

"Uphill-going slashes, they point up to the right."

She gave me a beady-eyed look and said, triumphantly:

"Oh, so you

really mean

backslashes."

Yeah, whatever, I see that you're new to the Internet. Let me quickly finish spelling the URL and get out of this room.

Later that day I asked the other instructor just which course she was teaching that week. Yes, it's really CASP. And yes, they all have Security+ and want the follow-on certification. And the student with the bizarre unawareness of the format of URLs? Probably about the middle of the group as far as background knowledge went.

Psychological Exploits

Another person who, like me, does consulting work and teaches courses from time to time, told me about a visit to (ISC)2 headquarters. The receptionist encouraged him to pick up some brochures describing their various certifications and the testing process. He was surprised by what he read.

The printed material that they hand out at trade shows or at their office describe some things that you won't find on their web site. In their brochures, they say that they artificially increase the difficulty of the exams through psychological measures.

For example, on their more popular exams such as CISSP, they use what they call "CAT" or Computerized Adaptive Testing. As you progress through the exam, your performance so far dictates what happens next. Their website says that if you do better than expected, you will reach the required number of correct answers more quickly, and be done and pass the test in fewer questions and less time. That's true, but...

What they mention only in the printed material is that they do this because it disorients and worries the person doing the exam. If they're doing better because they know the material, they will get questions that are more difficult. You never know how many questions are really left, and so the result is that people are made to feel that they're doing much worse. This increases stress, and makes the person do worse.

Language Traps

Both CompTIA and (ISC)2 have cluttered their questions with unneeded details for a long time. They describe some scenario using someone's name, their job title, the company's market segment, and so on. The actual question is buried in all that irrelevancy. But then things got worse.

In the early to mid 2010s, CompTIA started converting some of questions so they really test the subject's ability to realize that it's a linguistic question, and then carry out a grammar analysis. I would warn students about this in a CISSP or CCSP course, and soon some of them contacted me after passing the exam to report that (ISC)2 had also adopted this trick. Here's one of several examples I have recently used when teaching test-prep courses:

You want to use a system that can protect communication by authenticating the server, and also providing a copy of the server's public key in a trustworthy format. A provider of trusted certificates will only provide one when you follow their rules. There is a protocol that you can use to check in real time whether a certificate should be trusted or not. You must have a copy of the currently untrusted certificates locally, to reduce network traffic. Rather than a complete copy of the key, you may refer to its hash instead. There are ways to prevent a breach today from exposing secrets based on keys in the past. What do you need?

- TLS

- CPS

- OCSP

- CRL

- thumbprint

- PFS

All the choices are correct, relevant, and part of the story. I have made it easier that what you would encounter in the exam by putting the answer choices in the same order they are referenced in the question text:

| "a system that can ... in a trustworthy format" | = | TLS, Transport Layer Security |

| "the rules" | = | CPS, Certificate Practices Statement |

| "a protocol" | = | OCSP, Online Certificate Status Protocol |

| "copy of the revoked keys" | = | CRL, Certificate Revocation List |

| "its hash" | = | thumbprint |

| "exposure today doesn't expose keys from the past" | = | PFS, Perfect Forward Secrecy |

"What do you need?" is the actual question. One of the sentences in the story says "You must have", it's a requirement. The others state that the item provides some feature, or describe your plan.

The requirement is for a local copy of the CRL, which is used for a step that's less obviously part of the certificate analysis process. This makes it a better question from the CompTIA point of view. Less commonly considered makes the question more challenging.

If you can't answer the linguistics question, you can't get to the cybersecurity question. You typically have to find the transitive verb in the perfective aspect. That is, the verb that takes a direct object and describes a completed action rather than a continuous one.

Ancient History and Fiction

In the late 2000s through the 2010s I frequently taught the Security+ test-prep course. CompTIA added a question about Thicknet in 2015. I had last seen that technology in the early 1990s, so about twenty years after its disappearnace they added a question about it.

Someone has removed the terminator from the end of a segment of Thicknet cable. What is likely to happen?

"The elders will burn them to death for being a witch" might be an appropriate answer.

I'm sure that I had a number of students who were born after I last saw a working segment of Thicknet cable. But they were likely to get a question about this technology and so I had to tell them that it would result in degraded to totally interrupted communication. At least there weren't any Token Ring questions, as far as I knew.

The DES cipher was developed in the early 1970s. The contraption known as Triple DES (or 3DES or TDES) was described in 1981, and that was replaced by AES in 2001. Meanwhile, the SHA-1 cryptographic hash function was published in 1995, replacing the whole MD1–MD5 series. However, into the mid 2010s students could expect questions about DES, MD5, and even MD4 on the certification exams.

Sure, it's important to know that the continued use of old ciphers and hash functions in legacy software is a risk. But all you really need to know is that they're old and need to be replaced, or protected behind a firewall or air gap. There's no benefit outside the exam for memorizing details about precisely how bad they are, or how outdated ones compare to each other. Or truly esoteric ancient history, such as how DES was derived from a cipher named Lucifer that was developed at IBM.

Similarly, questions about the long-replaced WEP wireless protocol, known to be easily exploited by 2001 and superceded by WPA in 2003, remained in the question pool through the mid 2010s.

So-called "warchalking", described on someone's blog in 2002 and immediately discussed in online and print publications, seems to never actually happened to any significant degree. But questions about it remained in both Security+ and CISSP question pools through the late 2010s.

The Security+ exam in particular devolved into a quiz

about 1990s cybersecurity when the calendar reported

that it was the mid to late 2010s.

Smurf, Fraggle,

Kerberos (misspelled "Kuberos") uses nothing but DES,

c:\SYSTEM32 still contains the Windows OS,

war-dialing attacks against modem banks are a big worry,

malware spreads on floppy disks,

and hackers hide their code with ROT-13.

Then there were all the questions about the security of the RSA asymmetric cipher being based on "the difficulty of factoring large prime numbers". The definition of a prime number, of any size, is that it cannot be factored.

These weren't one-time errors. I had to take the Security+ exam annually, and the nonsense about "factoring large prime numbers" reappeared year after year. You shake your head, select the wrong answer they believe is correct, and sure enough, my score reports that I missed nothing in the cryptography domain.

Learning to Pass a Test, Versus Actual Learning

An op-ed in The New York Times, "There Are Better Ways to Study That Will Last You a Lifetime" briefly explained how most people's expectations and assumptions about learning are wrong.

Rereading a textbook makes the content feel familiar. But judging that content is familiar and knowing what it means — being able to describe it, being able to use that knowledge when you think — are supported by different processes in the brain. Because they are separate, familiarity can increase even if knowledge of the meaning doesn’t increase.

"Different processes in the brain" refers to "Recollection and Familiarity: Examining Controversial Assumptions and New Directions", a paper in the medical journal Hippocampus.

The op-ed described an experiment involving students:

A week later, everyone returned for another test, and the results showed how misplaced student confidence was. The people who had studied just once (and recalled the material three times) remembered the passage best. The worst memory was shown by those who had studied the most — and had been the most confident about their learning.

The op-ed's author had recently written Outsmart Your Brain: Why Learning Is Hard and How You Can Make It Easy.

Amazon

ASIN: 1982167173

Remote "Exam Integrity" Software is Racist

The extremely shady "educational integrity" industryIt simply is. People who aren't of pasty white complexion are far more likely to be falsely accused of cheating during online exams. Even if they aren't disqualified, frequent unneeded warnings greatly increase the stress level.

See this New York Times article for an example, and Cory Doctorow's article for several more.

Police Facial Recognition Technology Can’t Tell Black People ApartThis is just one aspect of a larger fundamental problem. Science had an article in April 2023, "Rethink reporting of evaluation results in AI":

Take, for example, a system that was trained to classify faces as male or female that achieved classification accuracy of 90%. Based on this metric, the system appears highly competent. However, a subsequent breakdown of performance revealed that the system misclassified females with darker skin types a staggering 34.5% of the time, while erring only 0.8% of the time for males with lighter skin types.

The faultiness and bias didn't seem to bother (ISC)2, who said that online exams did not meet "security standards" defined entirely in terms of protecting the exam content and keeping the pass rates low. They announced:

After two extensive pilot programs using the most stringent security protocols available, (ISC)2 has concluded that online proctored exams do not satisfy its standards for security and integrity for exam administration. (ISC)2 will continue to explore and monitor online proctored exam practices and may initiate additional pilots as technology and practices for online exam delivery and monitoring evolve.

This Nonsense Isn't Helpful, And It Actively Harms Cybersecurity

Pundits now use "PAM" to mean "Privileged Access Management". That's an acronym that we don't need. But what's worse, it's ambiguous and confusing. Someone who works in cybersecurity should know about Pluggable Authentication Modules and will assume that "PAM" has that original meaning.

Why did this happen? Very likely because someone wanting to maintain a certification decided that it was a good idea to get continuing education credit by writing something in which they make up new buzzwords, and this was the result. "Zero-Trust Architecture" seems to be another unneeded buzzword. Yes, what it's about is a good idea, but it wasn't as if this was some totally new concept. Someone made it up in a blog, one of the volunteers authoring questions for (ISC)2 liked it, and now everyone has to memorize it.

I have fallen victim to this myself. Some of what students must memorize is wrong. I have had to repeat the nonsense so many times that I will sometimes say it without thinking carefully.

None of these certifications really gets beyond a very

introductory look at the basics of cryptography.

One thing you do have to get across is the distinction

between symmetric and asymmetric cryptography.

Of course, a student in a test-prep course isn't there to

learn how this technology works, they need to learn how

to select the supposedly "correct" answer choice.

To do that, you must teach them this incorrect mantra:

"Symmetric encryption is for large files,

asymmetric is for small files."

No, that's wrong in the real world. Asymmetric encryption is totally impractical for anything appropriately described as a "file". Asymmetric encryption is only applied to symmetric session keys and hash outputs, things no larger than 512 bits, or 64 bytes. What's worse, "file" implies storing something on a disk, an extremely dangerous thing to do with a session key.

Bad Exams Aren't a New Problem

An article in Inference Review described the situation in China. The Han dynasty of 202 BCE to 220 CE had used written examinations to assign and promote men to positions in government. Then the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties expanded the exams to the recruiting and selection of new officials.

The later Ming and Qinq dynasties of 1368–1912 aimed for smaller governments and thus fewer bureaucrats. Pass rates fell to 1 in 100 and sometimes as low as 1 in 200.

DURING THE EARLY twentieth century, the Chinese civil service examinations became in China, as well as elsewhere, a symbol of the failure of the Chinese dynastic state and the backwardness of Chinese society. Chinese intellectuals saw the examinations as an obstacle to modernization, to the spread of modern science and technology, and to democratization and the broadening of education to the population at large. The “eight-legged essay” or baguwen, one of the genres tested in the examinations, was then typically singled out as the embodiment of a system that had forced millions of students to mindlessly memorize classical texts and reproduce them in calligraphic writing in a strictly parallel format that left no space for individual creativity and curricular innovation.

Next:

Which Programming Language Should I Learn?

Someone asked me, "Which programming language should I learn?" It depends on what you want to do.

Latest:

The Recurring Delusion of Hypercomputation

Hypercomputation is a wished-for magic that simply can't exist given the way that logic and mathematics work. Its purported imminence serves as an excuse for AI promoters.

Previous:

How Not to Get a Job

In which I stumbled into a teaching job through mistaken identity, with the involvement of a doomsday cult.