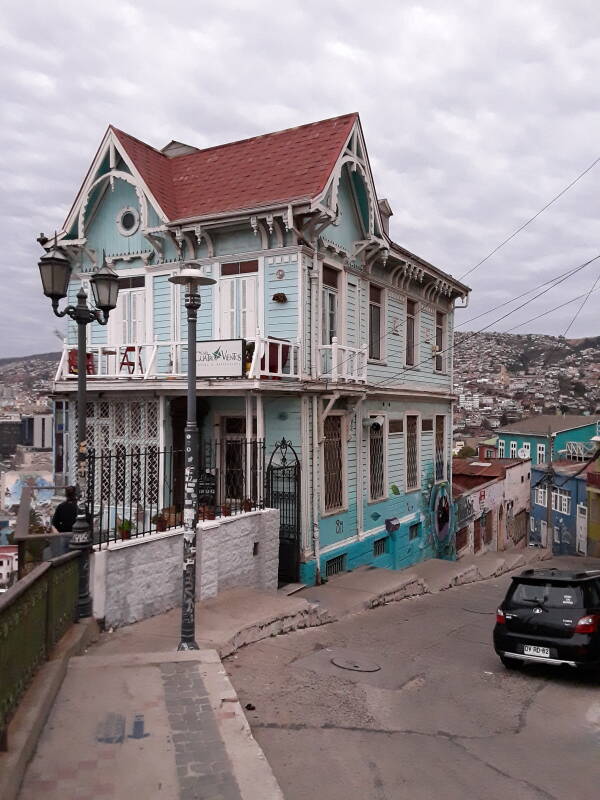

Puerto District in Valparaíso

Barrio el Puerto

Valparaíso is one of the South Pacific Ocean's most

important seaports.

Before the Panama Canal opened in 1914,

Valparaíso was a primary stopping point

for ships traveling between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

19th century sailors called the port city

The Jewel of the Pacific and

Little San Francisco.

Valparaíso is still the main port for shipments between

Chile and East Asia.

There are many Chinese-owned businesses throughout Chile.

They rely on this port.

Valparaíso is the main container and passenger port

in Chile.

It handles 10 million tons of cargo annually.

There are about 50 cruise ship port calls through the summer,

carrying around 150,000 passengers.

Armada and Plaza Sotomayor

The headquarters of the Chilean Navy is in the Puerto district. Edificio Armada de Chile faces the two-block Plaza Sotomayor.

Some days a market fills the half of Plaza Sotomayor next to the Armada.

The half of Plaza Sotomayor closer to the port has a monument to Chilean national heroes, topped by Thomas Cochrane, an amazing figure.

Start with his father, Archibald Cochrane, 9th Earl of Dundonald in Scotland. The title came with a little land but next to no money. After service in both the British Army and Royal Navy, Archibald turned to invention.

He built a plant to process coal into coke. Coke was produced in China in the 4th century, and began being used there for heating and cooking by the 9th century. Five centuries later, the British caught on. Coal is converted into coke by baking it in an airless kiln, much like converting wood into charcoal. The two major byproducts are coal tar and coal gas.

Archibald built a coking plant, to supply fuel to iron works. He was producing coal tar on an industrial scale. What could he do with that messy byproduct? He developed a method of treating wood with coal tar, which could protect ship's hulls from worms and barnacles. He took his material and process to shipyards throughout Britain, but none were interested.

The problem, you see, is that from the shipyard's point of view, even untreated ships last too long. They want to keep building more and more replacement ships, so a preservative was of no interest. If his product had made ships rot faster, then they might have been interested.

OK, ship builders don't want long-lived ships, so Archibald went to the Royal Navy. Surely they want to preserve the ships they buy. Surely they want to reduce maintenance and replacement costs.

Well, no. Men in the Admiralty offices received kickbacks from shipyards. The Royal Navy, controlled by officials enriched by this naval baksheesh, also had no interest in ship preservation.

Archibald had patented the coal tar process in 1781, but no one was interested. Once his patent expired, the Royal Navy became interested. Coal tar found many uses through the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s. It's a complex brew of hydrocarbons, useful for products ranging from drugs to dyes and paints.

Meanwhile, Archibald tried to do something with the plentiful coal gas byproduct. It was highly flammable, he had to do something with it, but found no interested buyers. So, he simply burned it off. People were startled for miles around by the extremely bright light it produced when he started burning it off at night.

Again, China was way ahead, using natural gas for lighting around 300 CE. Coal gas had been known to be flammable for some time, but it was a scientific curiosity. Archibald had a patent for its production method, but there was no interest in using it for lighting, despite the spectacular demonstration provided by Archibald's factory waste gas burn-off.

Later, in 1808, the paper "Account of the Application of Gas from Coal to Economical Purposes" was presented to the British Royal Society. Gas began lighting the streets of London and Paris.

Archibald had been too far ahead of his time. He died in poverty in Paris, and his son became 10th Earl of Dundonald, still little more that just the title.

Thomas Cochrane

Thomas Cochrane was Archibald's son. His uncle Alexander Cochrane had gotten him listed as a crew member on the books of four Royal Navy ships starting when he was just five years old. This common illegal dodge called false muster accrued years of purported service needed for promotion before one even joined the Navy.

Thomas joined the Navy in 1793, when he was 17. With his fictitious 12 years of service and real aptitude for the Navy, he rapidly advanced in rank. Britain and France were fighting at sea, and Cochrane was in the middle of it.

At that time, after a Royal Navy ship had captured an opposing warship, or even a merchant ship, the captain and crew shared the spoils. Napoleon called Cochrane Le Loup des Mers or "The Sea Wolf". On top of the nationalized piracy practiced by navies, there was of course no long-distance communication. The Royal Navy had no idea what its ships were getting up to.

Amazon

ASIN: 030435659X

Cochrane was an inventor like his father, starting in 1804 with a superior ship's lamp used for convoy navigation.

In 1806 he had a highly maneuverable galley built to his design, using it to attack French ports.

In 1812, he devised an assault plan to combine bombardment ships (old hulks converted into gigantic crude mortars), explosion ships (enormous floating bombs), and "stink vessels", a form of gas warfare.

Cochrane became interested in politics, and was elected to the House of Commons. There he managed to make powerful enemies both within government and the Admiralty.

He was convicted in the Great Stock Exchange Fraud of 1814, and dismissed from both Parliament and the Royal Navy. His knighthood was also taken away. So, he became a mercenary naval leader, soon hired by the independence movement of Chile to establish and lead its navy.

Bernardo O'Higgins appointed Cochrane Vice Admiral in command of the Chilean Navy in 1818. He organized the navy along British lines, and applied the blockading and raiding techniques he had found so useful against French and Spanish forces.

With both Chile newly independent from Spain, and Peru nearly so through the help of Cochrane's navy, Cochrane left the Chilean Navy in 1822.

He then took command of the Imperial Brazilian Navy in 1823, picking up the title of Marquess of Maranhão. In Chile and Brazil, as before that in Britain, Cochrane constantly quarreled with the government over pay and prize money, and made accusations that government officials were conspiring against him. He left Brazil in late 1825 and returned to Britain.

Greece was fighting for independence from the Ottoman Empire, so Cochrane went to his fourth navy. He was involved in the Greek naval campaigns from March 1827 to December 1828, but he was not as successful as he had been with the Royal Navy or in South America. He resigned his Greek commission and returned to Britain.

Cochrane's enemies in government and the Admiralty eventually retired or died. He was restored to the Royal Navy's officer list in 1832, but he refused to take a command until his knighthood had been restored. That took 15 years, during which he rose in rank in the list of flag officers.

Meanwhile he wasn't sitting idle. He was experimenting with steam powered ships, developing a rotary engine and propeller.

Queen Victoria personally intervened and reappointed him Knight of the Order of the Bath in 1847, and he returned to the Royal Navy. He served as Commander-in-Chief of the North America and West Indies Station from 1848 to 1851. The Royal Navy considered giving him a command in the Baltic during the Crimean War of 1853-1856, but decided that he was too likely to risk the fleet in a daring attack. He kept refining and resubmitting his assault plan for bombardment ships, explosion ships, and stink vessels, but the Royal Navy kept turning it down.

Amazon

ASIN: B0040FMG2G

Amazon

ASIN: 0060932295

Thomas Cochrane was the basis of Horatio Hornblower in C.S. Forester's novels, and Jack Aubrey in Patrick O'Brian's novels. He is one of the main characters in Bernard Cornwell's Sharpe's Devil.

Toward the Waterline

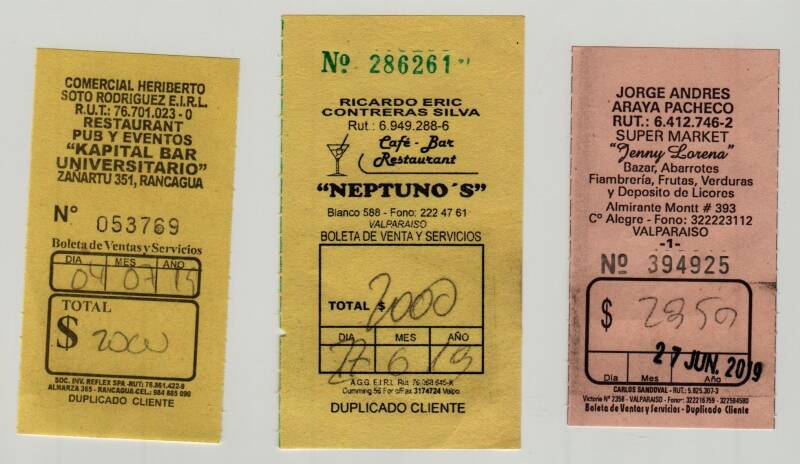

The Neptuno Bar and other pubs are just off the plaza. Maybe stop in there for a vino tinto.

Purchases in Chile usually involve hand-written receipts on pulp paper. Just C$ 2,000 for a vino tinto, less than US$ 3.

We'll continue west through Barrio el Puerto.

Cerro Artilleria

Ascensor Artilleria can carry us up Cerro Artilleria. Artillery Hill, this was an obvious defense point for the harbor.

You pay just C$ 100-300 to ride one of the historic ascensores. There once were 30 of them, now 16 remain. They're designated as National Monuments of Chile.

Only one, Ascensor Polanco, is truly a vertical elevator. The others, like this one, are funiculars.

The Port

There's a great view over the port from 21 de Mayo, the May 21 viewing point next to the naval museum.

A large COSCO or China Overseas Shipping Company ship was in the port on this day. About 10 million tons of cargo moves through here each year.

Copper and fruit are major exports of Chile leaving via this harbor.

I'll walk back down the cerro.

Buildings are painted in many different shades.

Even the alleyways are filled with art.

The excursion boats are idle in mid-winter.