Tiryns | Τίρυνς

Mighty-Walled Tiryns

Tiryns, Τίρυνς in ancient Greek or Τίρυνθα in modern Greek, was a Mycenaean fortress near the Argolid Gulf in the Peloponnese. It's large, 300 meters long and 45 to 100 meters wide, on a low hill up to 18 meters above the flat surroundings. The site was first settled by late Neolithic people in the 6th millennium BC.

Mighty-walled Tiryns, the ancient fortress.

Between about 2100 and 1900 BC, during the Old Bronze Age, Indo-European people crossed Anatolia, moved through Troy, and continued across the Dardanelles to the west and then south through the peninsula we now call Greece.

The existing settlements in the mainland were primitive, and these new arrivals brought an advanced culture. A number of small kingdoms were established. In addition to the one at Tiryns, there were kingdoms in nearby Mycenae, Pylos, Argos, and Korinthos.

Map of Greece showing the ancient fortresses of Tiryns and Mycenae.

The kingdom of Mycenae became the most influential, leading to Mycenaean becoming the term for the entire civilization of that area and time. It had contacts of trade and culture with the advanced civilization on Crete.

The Fortress

Tiryns also reached its peak in the period 1400-1200 BC. Homer referred to it as "mighty-walled Tiryns" because of its massive defensive walls. In ancient times the myths linked Tiryns to Heracles, sometimes describing it as his birthplace.

It's hard to distinguish myth from history in this area, but some time around the 14th century BC there seems to have really been a King Agamemnon at nearby Mycenae. Agamemnon's brother was Menelaus, and Menelaus' wire Helen was abducted by Paris of Troy and taken back to his city on the northwest coast of Anatolia. Agamemnon then commanded the Achaean forces (what we often mis-label as "Greek" today) in the Trojan War.

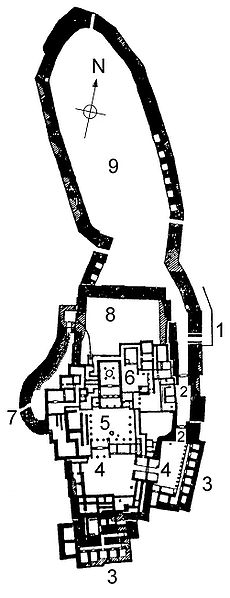

You approach the site as visitors did in the past, coming around the north end (at top in this plan) and coming up a large entry ramp, labeled "1" in the plan below.

Continuing toward the palace, you would have continued up ramps and through two gates or fortified doors, both labeled as "2".

The overall layout of the fortress was for defense against intruders. Notice that on both the exterior ramp (1) and passing through the two gates on the interior ramp (2), you would be ascending with an inner wall to your right. The warriors of that time would carry a sword in their right hand and a shield on their left arm. This design exposed them to defenders on the massive walls pelting them with spears and rocks on their unshielded side.

Entering through that outermost gate, to your right would be an area making up about half the citadel, labeled "9". That area is slowly being excavated and studied. It was the non-royal precincts, the part of the fortress that was not the palace. It was maybe four to five meters lower than the palace.

The walls are referred to as "Cyclopean", due to the belief in Classical times that such enormous stones could only have been manipulated by those one-eyed giants.

The walls remaining today reach heights of 7 meters, but they were originally up to 9.1 meters tall. They were six meters thick, and constructed from enormous stones.

Plan of Tiryns:

1: Entry ramp

2: Entry toward palace

3: East casemates

4: Great propylaia

5: Inner court

6: Megaron

7: Postern

8: Inner courtyard

9: Homes and shops

— Original from Wikimedia Commons

Check ferry schedules and buy tickets:

Once through those gates, you were in a courtyard outside the Great Propylia (4). Below were the casemates (3), used as storage areas and military barracks. Turning to your left, you entered the royal palace. The palace was laid out much like the one at Mycenae.

You pass through a doorway into the Great Propylia (4), the outermost courtyard of the royal palace. From there you walked between a pair of columns and through the Smaller Propylia, and into the Inner Court (5).

The Inner Court was large, twenty by fifteen meters. It was surrounded on three sides by porticos supported by columns. See the small circles indicating those columns. The fourth side, opposite the entrance, was the outer wall of the Megaron.

The Megaron was the center of power. It was the series of three rectangular chambers just above the label "5" and to the left of the label "6" on this plan. Approaching the heart of the Megaron, you cross its porch, then its vestibule, and finally entered the roughly square Megaron itself. It had a central hearth surrounded by four columns, see the circle and four dots just left of the label "6" here. The king's throne was along the wall to the right of the entrance. The Megaron walls were covered with stucco and then decorated by Cretan style paintings.

The royal apartments were between the Megaron and the entry ramp, to the right of the label "6" here. The area labeled as "8" was an inner courtyard within the core palace area of the fortress. Now it openly overlooks the lower city in the north half of the citadel.

The Decline of Mycenae

Mycenaean power began to decline around 1200 BC. It's not known if this was caused by an attack from outside Greece, or if it was warfare within the many Mycenaean kingdoms.

The palace area was occupied continuously through the middle of the 8th century BC. Tiryns and Mycenae were insignificant settlements at the beginning of the Classical era, but they managed to send 400 men to the battle of Plataea in the Greco-Persian Wars.

The nearby kingdom of Argos completely destroyed both Tiryns and Mycenae in 486 BC and transferred their populations to Argos.

Tiryns was completely deserted by the 2nd century AD when it was visited and described by Pausanias, a Greek traveler and geographer. He wrote that not even two mules working together could moved the smallest stones used in the outer walls.

Let's Explore

Here you see the fortress from the southwest. We're looking up at the highest part, where the palace was located.

The massive stone walls of Tiryns.

Tiryns as seen from near the entrance.

From the northwest, we look over the lower city and up toward the palace area.

One of the outermost approach ramps leads up toward the entrance. If you were trying to get in by force, remember that people would be throwing spears and large rocks from above and to your right, while your shield is on your left arm. I suppose you could always try walking backwards...

Ramp around the exterior of the fortress walls

The well protected entrance into Tiryns.

Now we're through the outermost gate, and we have turned left to continue up the ramp through the two gates and toward the palace. Again, if you were unwelcome, the defenders would be up on that wall above your right side.

The main gates were set into some very sturdy frames! Here is the monolithic threshold and fragments of the monolithic gateway frames.

The doorway of Tiryns' main entrance.

This shows how the gate would be secured. Thick wooden doors would be closed, and then barred from behind by a pole fitting into a hole at one end.

The frame of the main gate.

This is very impressive cylindrical stone boring work for construction in the 13th century BC!

Bored hole for the gate crossbar.

This was the view for the defenders. Get your big rocks handy. "Squash those pesky Argolians!"

View from above of the approach to the main entrance.

We're outside the Greater Propylia, looking toward Nafplio from the high southeast corner of the citadel. The town is below the high bluff to the left and extends up the lower one at center. The Argolid Gulf is beyond those bluffs and on this side of those more distant hills.

View from Tiryns toward Nafplio and the Argolic Gulf.

The eastern casemates were used for storage and as military barracks. Erosion has left them partly open, this would have been a dark and gloomy area back in the day.

The east casemates.

Below, we're looking from the north end of the enclosed palace, from the Megaron, across the inner courtyard of the palace. Beyond that there's a sharp drop down to the lower city.

View across the fortress from the palace area.

Residential and business area of the fortress.

There just isn't much to see of the palace itself. There are bases of some of the walls, some floor, but it's very much a "site of" thing that only makes sense with a good reference like the Michelin Green Guide. For even more detail, get the Blue Guide. Blue Guide

Amazon

ASIN: 1906261423

Amazon

ASIN: 0393328368

Below is the lower city. Wall foundations show the general layout, but there's little information about just what you're looking at.

Seige warfare usually hinges on water supplies. A strong fortress like Tiryns could hold out indefinitely against the military hardware of the day, but its people had to survive. Water supply was far more critical than food. That was true in the Bronze Age, and remains true today.

Just as at Mycenae, Tiryns had water cisterns located underground outside their walls. Small passages, their opening seen here, led down at an angle through the thick walls and underground.

Passages to water cisterns.

Cistern area outside the walls.

Here we see the walls just outside those passages. The tunnels led down to the underground cisterns just outside the walls.

Logistics:

Mycenae is a very easy day trip out of Nafplio.

Catch one of the frequent buses running from Nafplio to Argos or other destinations to the west or north. Tell the driver that you want to get off at Tirintha. Watch for the site on the right side of the highway. The entrance is at the end away from Nafplio, so you want to get off just past the huge walls. The first picture at the very top of the page shows the view as you arrive at the end toward Nafplio. Once you see that, the bus should let you off at the other end. You can flag down a return bus from the opposite side of the highway.

Alternatively, you could walk. I took the bus to the site and then walked back. It's probably three kilometers from the site to Nafplio, with plenty to see along the way.

The train makes for a pleasant way to reach Nafplio if you're coming down from Corinthos, Athens, or the northern shore of the Peloponnese.

I stayed at Dimitris Bekas' guesthouse. It's a great place and the main budget option in the center of town. It's at Efthimiopoulou 26. Get to the Roman Catholic church, go up the stairs to your left, take the first passageway to the right, take the first major passageway to the left. No website, and as far as I know, no e-mail. Just call him up and make a reservation:

Dimitris Bekas

Efthimiopoulou 26

Nafplio, Greece

+30-2752-024-594

Dimitris Bekas' guesthouse or domatia in Nafplio.

Interior of guest room.

Taking in the sunset over Nafplio harbor.

The sun sets on Nafplio.

The castle of Bourtzi in the Nafplio harbor, built by the ruling Venetians in 1473.