To My Guesthouse

To My Guesthouse In Aizu-Wakamatsu

I had traveled by Shinkansen from Tōkyō

to Kōriyama,

then on the Ban-Etsusai Line through five other stops

to Aizu-Wakamatsu.

Guesthouses at Booking.com I had reserved a room at Mooi Guesthouse through booking.com,

so it was time to make my way there from the station.

It was a very nice place to stay

and it was conveniently located,

about twenty minutes' walk from the station.

I realized later that I could have saved a kilometer's trek

by waiting a short time for a local train

from the main Aizu-Wakamatsu Station

to Nanukamachi-eki,

the small unstaffed station on Nanuka-machi dori,

Nanukamachi Street,

a short distance from the guesthouse.

However, that would have bypassed the extremely helpful

Tourist Information Center in the main station's lobby.

Akabeko at the Station

It worked out well that I walked to the guesthouse from the main station, instead of staying within the station to take a local train to the small station near my guesthouse.

I noticed the Tourist Information Center just off the main lobby in the station and visited it when I first arrived. They were very helpful, giving me two local maps, a map of the Mount Bandai area, bus and train schedules, and further information. I also bought a two-day pass good on all regional trains and buses, and verified some schedules since this was the beginning of the major holiday period of Golden Week, Japan's biggest holiday period.

A statue of the legendary cow Akabeko stands outside the main station entrance.

The monk Tokuichi was supervising the construction of the Enzō-ji temple in Yanaizu, a town 18 kilometers west of here, in 807 CE.

The legend is that Akabeko, whose name means "Red Cow", became quite obstinate about remaining inside the temple. When the temple was finished, the monks simply could not get Akabeko out of the temple. Akabeko became the permanent temple cow, and became a symbol of zealous devotion to the Buddha. Some versions of the legend say that Akabeko surrendered her spirit to the Buddha and turned to stone.

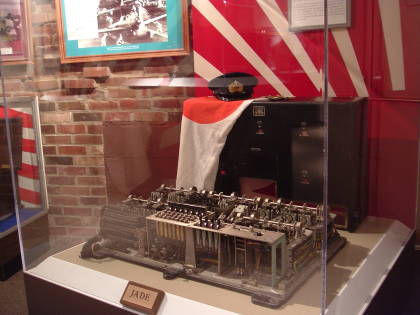

Warlords called the shōgun ruled Japan from 1185 until 1868. The Emperor was believed to be directly descended from the gods and therefore stayed in Kyōto and carried out various Shintō rituals, while the warlords ran things.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was a samurai and daimyō. He became a high-ranking advisor of Oda Nobunaga, then the effective ruler of much of Japan. One of Nobunaga's generals attempted to assassinate Nobunaga in the Honnō-ji Incident in 1582. It was an unsuccessful assassination, but its nature of betrayal led both Nobunaga and his heir to perform seppuku or ritual suicide.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi took control, and became the effective ruler of much of Japan by the mid 1580s. However, he never reached the level of being proclaimed the shōgun.

Hideyoshi sent Gamō Ujisato to be the daimyō or warlord controlling Aizu in 1590. The Aizu domain was along the northeastern edge of the territory controlled first by Nobunaga and then by Hideyoshi.

Ujisato heard stories about Akabeko, and directed his court artisans to create what may have been the world's first bobblehead doll. The same design remains the same, papier-mâché finished with paint and then lacquer. The head and neck are hung by a cord within the opening at the front of the body. When the doll is moved, the head wobbles up and down and side to side.

The large Akabeko figure at the train station is built the same way with a fiberglass body and a wobbling head.

It's more than the search for kawaii, although some of the small Akabeko charms and figurines are certainly kawaii. People came to believe that an Akabeko figure would ward off smallpox and other diseases. Red amulets were already believed to be effective against smallpox. Then the people around Aizu began to believe that they were noticing a trend in which children who owned Akabeko figures did not catch smallpox.

Some belief in red Akabeko figurines as disease-preventing charms continues today.

A capsule machine at the station sold Akabeko figures. Maybe you should get one just to be safe.

From the Station to My Guesthouse

I headed south from the station with a useful supply of maps, transportation schedules, and traditional smallpox-prevention tips. South to the intersection with the cemetery monument company on the narrow point, then down the street to the right.

I crossed Nanukamachi-dori and continued to the third street beyond that. Turning to the right, I was looking down the street to my guesthouse.

This is Japan, there might be a railing next to the sheer drop at the intersection, but continuing down the street it's the responsibility of the pedestrian or driver to not fall into the drainage channel. But almost no one does.

During four weeks in Japan, I didn't see a single car with a broken taillight, dysfunctional headlight, damaged body panel, or other visible damage. Back home in the U.S., many of the cars I see daily have obvious unrepaired damage.

At the Guesthouse

Guesthouses at Booking.comI had reserved a room at Mooi Guesthouse through booking.com. Their app's built-in map function provides vague directions, but it ties into Google Maps. If all else fails, the booking record includes GPS coordinates — in this case, N 37° 29.869', E 139° 55.278'. It's three streets south of Nanuka-machi-dori. three streets to the east of Nanuka-machi Station. The sign is subtle.

I asked about the name "Mooi". I was thinking that it was because that was what Akabeko says. No, the Japanese say that the cow says モーモー or something close to "moh-moh". "Mooi" is a Dutch name, my innkeeper had studied in Amsterdam.

As usual, leave your shoes at the outer door.

I had a private room with a futon on a tatami mat.

The shared bathroom was just down the hall.

The large shared room had a kitchen in one corner. These pictures are deserted because I took them around 0630 in the morning. I was the only person up at the time, still waking up early because I had crossed ten time zones from Chicago to Tōkyō only two days before.

There was great Wi-Fi connectivity and comfortable seating.

The shower and laundry room was off to the side.

The main electrical panel was beside the staircase leading to the upstairs rooms. I was struck by the building having a 30 amp main circuit breaker. Japanese electrical power is 100 volts AC, so that means 3 kilowatts for the entire place. Appliances in Japan are designed to not need large amounts of electrical power.

The plug standards are NEMA 1 and NEMA 5 in the U.S. and JIS C 8303 in Japan.

U.S. and Japanese plugs and sockets are not exactly the same, but they're close enough that you can simply use a U.S. power cord in Japan, and vice-versa. The blades on Japanese plugs are very slightly shorter.

I wouldn't expect you to carry any electrical equipment that doesn't have a switched-mode power supply — You will definitely have smart-phone chargers, maybe a laptop computer, and possibly a chargeable razor. All those have switching power supplies, which accept a broad range of voltages and frequencies. Japan uses 100 V AC at either 50 or 60 Hz (NE vs SW of Tōkyō), the U.S. uses 120 V AC at 60 Hz, and those are trivially different to a switched-mode supply.

The one source of possible trouble with electricity is that Japanese outlets are all polarized (one blade slightly wider than the other), but only a few are grounded with a third pin. I needed a grounded-to-ungrounded adapter for my laptop, and I had forgotten about this since my last visit. No real problem, I had a full day in Tōkyō at the start of the trip and had planned to go to Akihabara anyway. I bought one there.

Making Plans

The map of the area around Bandai-San was pretty straightforward.

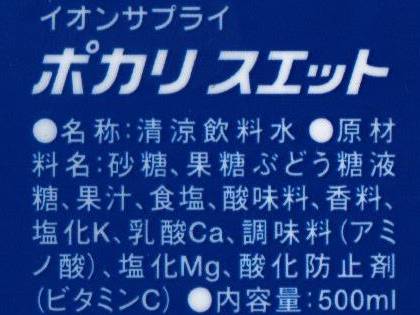

The bus and train schedules, however, were overwhelming. Other than route numbers and times, they were almost entirely kanji, very little of the phonetic hiragana characters. I had only just barely kept track of which schedule was for the bus and which was for the train. Yes, read down a column to follow one run, but what are the stops?

As soon as I got settled in, I went into the shared room and talked to my innkeeper. He helped me to label a few of the columns and rows. The first of these is the Banetsu West Line train schedule.

In the column topped "220D", I would take the 0735–0805 train from the main Aizu-Wakamatsu Station to Inawashiro. That's train 1226M. I could have boarded train 222D at the nearby Nanukamachi-dori station at 0716 and ridden about four minutes to the main station, but I wasn't confident enough this early in the trip. I just walked the twenty minutes to the main station. I was in Japan, there was plenty to see along the way.

Then, the bus schedule. See the left-most column in the upper (east-bound) table. I would arrive on the train at 0805, and take the bus leaving Inawashiro Station at 0815 and arriving at the west end of the Five-Colored Lakes trail at 0846. My innkeeper had recommended that I walk the trail from west to east, that was excellent advice! "Mus." marks the line with the stops at the art museum. I'll ride past it on the way there, and leave from there on the way back.

Nearby Ramen

Katakana &hiragana

The NEO ramen shop along Nanuka-machi-dori was a short walk away. Great food, no English on the menu but we managed. I got dinner there on three of my four nights in Aizu-Wakamatsu. Here's tonkotsu ramen and gyoza. Both of those are Chinese names for Chinese dishes, so they tend to be written in katakana as ラーメン and ギヨーザ making them a little easier to find in a menu.

Until, that is, you arrive in a smaller and more traditional town, where they're in hiragana as らーめん and ぎよーざ.

Sitting at the counter, there will be a water pitcher nearby. Also a small tray with oil with chili pepper and soy sauce.

Even the toothpicks are made with attention to detail in Japan.

This is a different ramen choice on a different night.

This is Kitakata ramen, from the nearby town famous for its twisted noodles.

In the morning I left by train to Inawashiro Station then by bus to the Five-Colored Lakes. While there, I would also visit the Morohashi Museum of Modern Art and see some of its Salvador Dalí collection.

Other topics in Japan:

Hideyoshi's young son was unable to hold onto power and Tokugawa Ieyasu was declared shōgun in 1603, beginning the Tokugawa shōgunate that lasted until 1868.