Seiryū-ji

The Great Buddha and its Temple Complex

I had come to Aomori to see the nearby prehistoric

Jōmon settlement,

occupied roughly 3900–2200 BCE.

While planning the trip,

I saw that

Japan's tallest seated Buddha statue

is nearby.

As you would expect,

it is in an interesting temple complex.

I wanted to see that!

But how to get there?

It's outside the east edge of the city.

But, it's very practical to get there

with a bus ride and a walk.

I was looking for Seiryū-ji,

the temple, and the

Shōwa Daibutsu,

the Shōwa-era Great Buddha.

Here we go.

On the E10 Bus

There is a bus that runs between Aomori Station and the parking lot at the temple. You can find out about it at the (as usual) excellent Tourist Information Office at the station. But where's the challenge in that?

Instead, the E10 bus would take me from Shiyakusho Mae, near where I was staying, to Higashi Kosenkyo, a reasonable walking distance from the temple. The E10 bus runs along a major street through the city that's actually National Route 4. Note that those locations are bus stop names. They're usable with Google Maps, but they might take a lot of walking and careful sign reading to find otherwise.

Google dynamically generates this map when you load the page. I intend for you to see a pretty straight bus ride west to east on Route 4 from Shiyakusho Mae to Higashi Kosenkyo. But if it isn't early morning through early evening in Japan, you may see a walk to the train station followed by a roundabout bus ride taking 55 minutes or more, and then another walk.

I found my way from my hotel to the starting bus stop. How hard could this possibly be? Also notice the nice system of tiled pathways that you find on sidewalks throughout Japan. They're there for blind people — straight stretches have long straight bumps, and a cluster of round bumps indicates an intersection or a transition to cross a street. And yes, the tiles cross the street. It's effective and helpful urban design. Coming from the U.S. this is, of course, completely foreign to me.

Here's how it's done in the U.S. This is at the corner where I live. We're looking across four lanes of traffic, where a four-lane road splits into two two-lane roads. Until it was routed around the city, this was U.S. Highway 231, which runs from the outskirts of Chicago to the Gulf of Mexico coast in Panama City, Florida. There's a tactile system of steel plates with bumps indicating that you have reached a sidewalk-to-street boundary. But now what would a blind person do? Wander out into traffic with no idea of the direction to the other side, and hope for the best.

Back in Aomori,

here's the city bus map in that shelter.

As I said, how hard could this possibly be?

Um, maybe a little complicated.

The bus lines have romanji labels like "E10",

but the locations are almost entirely in kanji,

the complex Chinese glyphs.

At this point the only kanji I could recognize

were those for small and large

(because they're on toilet flush handles),

yen (because you see that everywhere),

and for some peculiar reason,

mountain and north.

Japanese school kids

have to learn

80 kanji

to graduate from first grade,

a total of 1,026 for grades 1-6,

and another 1,110 in grades 7-9.

All I can recognize are:

大

小

円

山

北

And, the first-grade kids have to draw them using

correct stroke order and direction.

And here is the schedule for stops at this station. It's also somewhat overwhelming. However, working backward from the schedule I thought should be correct, with E10 reaching this stop at 0919, I saw E10 in the column at upper right, and in the row for 09 below that I saw "19", so yes.

Well, I was in Japan, where public transit is amazingly precise. I would wait here through 0919 watching the electronic displays above bus windshields to see if the E10 bus didn't show up as expected.

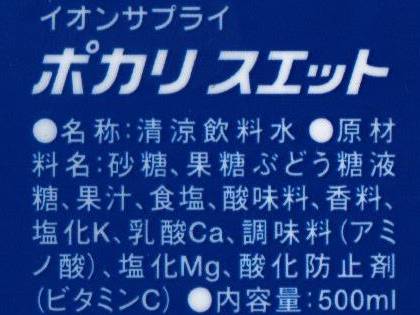

Of course it did. Now, the trick was to get on at the rear door and make sure to take a ticket from the machine just inside.

Here's my ticket, I got on at stop #3.

Now I could watch the panel at the front of the bus. It would cycle through displays, from time to time showing the next stop in romanji, and usually showing a table of numbers. That table showed the bus stops reached so far, with a number below each one showing the price in yen you must pay to get off after boarding at that numbered stop.

So, I would watch for our approach to Higashi Kosenkyo and keep my coins organized to easily pay the amount shown below stop 3 where I got on.

Walk From the Bus Toward the Temple

I managed to get off at the correct stop! It's not an exciting place, it's along the highway at the edge of town with the north side of the road lined with the collection of businesses you would expect to find there — furniture, tools, car parts, and so on. After a short walk to a signal and waiting to cross the highway, here's the view to the south. It's all farmland on that side. The temple complex is on the edge of the woods about a third of the way from left to right in this view. There's a Shintō shrine that I would visit on my way there, on a small wooded hill most of the way to the right. I would take a somewhat roundabout approach to the temple.

Here's my planned path. I started walking where I got off the bus at Higashi Kosenkyo. You can really see how there's an abrupt edge to a Japanese town. It's all built up until all at once you cross a road and it's all farmland.

I crossed the highway a short distance east of the bus stop. I continued onward along the highway to a major intersection, followed another highway south-southwest, turned off to the Inari shrine, then followed a side road to the temple complex with Shōwa Daibutsu. I took the direct route when I returned. I followed the farm roads, just dirt paths, along a fairly straight path from the temple entrance to the highway near the bus stop.

My somewhat wandering route was interesting. After I turned onto the second highway, I found these mysterious mechanisms behind the railing along the broad sidewalk. (This is Japan so of course there's a nice sidewalk along the highway.)

They seemed to be folded up, while one further along my route was partially unfolded.

Then there was a long stretch of this mechanical system, apparently folded up.

Then there was a stretch that was fully unfolded and deployed, and I finally figured it out.

I'm pretty sure that this is a deployable snow fence installed along the west side of this highway, just downwind on a typical day from some open farmland. It's a prime drifting location. The goal is to disrupt the wind-blown drifting snow, letting it fall behind and around this fence and limiting how much builds up on the highway. This section is in front of the Aomori East Disaster Prevention Station of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism. So, the section along this highway may be primarily for testing or demonstration. But I'm pretty sure that it's a snow fence.

When I taught the Linux course at Misawa Air Base, just a short distance to the east along the Pacific coast, they had told me about the local snowfall. I was there for the first week of December 2003, and the snow was between knee and waist deep. I thought that was a decent amount of snow. But they told me that was unusually light for that time of year, and the real snow should arrive soon.

Storms out of Siberia cross the Sea of Japan and pick up a large load of moisture. Then, when that reaches Aomori Prefecture, the northern tip of Honshū, it encounters mountains and a mix of winds leading to some of the heaviest snowfall in the world. Heavier even than parts of Hokkaidō, where Sapporo is famous for its annual snow festival.

Small portion of 1:500,000 Tactical Pilotage Chart F-10C from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

Inari Shrine

I crossed the highway from the Disaster Prevention Station and the snow fence onto a small road leading around a small forested hill. Around the south end of that, there was a torii over a path leading up to a small Shintō shrine on the peak of the hill.

The heavy hemp rope, straw tassels, and shide or white paper zig-zags are Shintō symbols. But, of course, the bright vermilion torii gate was the giveaway.

Steps led up to the shrine. There was a playground to the left.

This is an Inari shrine, thought to enshrine the kami Inari. Inari is the most popular of the Shintō kami. Out of the roughly 80,000 or more Shintō shrines, at least 32,000 are dedicated to Inari.

Inari is the deity of rice and agriculture in general, tea and sake, fertility, household well-being, and business and personal prosperity.

The myth says that Inari came to Japan at the time of its creation. She took the form of a goddess and descended from heaven riding on a white fox and carrying sheaves of some cereal that grew in swamps before rice was brought to Japan.

Inari is associated with foxes, who act as Inari's messengers. Foxes are typically depicted as guardians of the shrine. Here, however, there's a horse.

Seiryū-ji

From the shrine it was a short walk to the Seiryū-ji temple entrance. Actually, that's redundant, -ji means it's a Buddhist temple. -dera and -dō and -in are other common suffixes for Buddhist temples and related structures. Shintō shrines are usually referred to with -jinja or -go.

The Kōya-san Aomori Betsu-in is the first structure you see when you arrive. -in so it's also a Buddhist temple. I hadn't realized that this was a Shingon sect temple complex, associated with Kōya-san.

I had been to Japan three times on business trips which were of varying levels of frustration. Those started with a ridiculous trip in 1993 to solicit research funding from Japanese industry, while Japan was still struggling to deal with the collapse of their 1980s economic bubble. Then I taught a networking protocols course to EMC in Tōkyō in August 2001, and taught the Linux class at Misawa Air Base in December 2003. Both teaching trips were immediately followed by previous commitments back in the U.S., so I could only stay two extra nights on the first one and had to return the day after the second course finished. Japan seemed fascinating if I could get a chance to see it.

In 2017 I went to Japan on my own. It's large and complicated, and I was doing a mix of teaching and consulting so I could set my own schedule. So, I went for four weeks. This trip, in 2024, was my fourth four-week solo trip to Japan.

VisitingKōya-san

On the first solo trip in 2017, I went to Kōya-san. Regarding Shintō, like Socrates supposedly said, "I know that I know nothing". However, I knew at least a little about Buddhism, and I had read that Kōya-san was a big deal in Japanese Buddhism, so I went there. That trip and following ones have shown me that I was correct from the beginning — I didn't know, and still don't know, much at all about Shintō, and I have concluded that almost no one else does. More on this soon.

Anyway, this structure honors Kūkai, the Japanese monk who studied in China and brought a form of esoteric Buddhism to Japan in 806. He established a temple complex in the multi-peak summit of Mount Kōya, south of Kyōto and Nara. Right around that time the Emperor of China suppressed Buddhism due to its foreign origin, and so Kōya-san is the seat of the Shingon sect of Buddhism.

Tradition says that Kūkai was responsible for devising the katakana and hiragana scripts, based on simplified Chinese glyphs and used to write Japanese. They were needed for Japanese monks to read scriptures without having to learn how to read their Chinese translations or the original Sanskrit. Tradition also says that Buddhism had first reached Japan in 538 CE, when scriptures in Chinese translations were brought from Korea. With the kana scripts, all of it could now be more easily propagated.

You need to first enter the complex through the Mon or outer gate. Compartments on either side hold Niō statues representing fierce protectors of the temple grounds. They're based on the Greek hero Ηρακλής, or Herakles. Alexander the Great had taken Greek culture to the edge of India, where aspects were incorporated into Buddhist imagery that later spread north through Tibet and China, then east into Korea and Japan.

Pass through the gate between the protectors, pay a small admission fee, and start your visit with the Kōya-san Aomori Betsu-in. You remove your shoes as you step onto the wooden porch surrounding its upper story.

Inside, the main altar depicts Kūkai flanked by attendants. This is a case of venerating someone and not worshiping them. Compare this to a Christian church dedicated to a specific saint, with an image of that person above the altar.

However, even the brochure and site map provided by this very Buddhist organization used the English word "enshrine" to describe what's going on. That's very much Shintō terminology. Shintō says that one of its facilities enshrines a kami or deity or spirit, that the kami occupies or is contained within the shrine's honden, the most sacred part of the shrine as it's dedicated exclusively to housing the kami. Religion in Japan is very mixed up.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 led to the suppression of Buddhism and the promotion of a re-interpretation of Shintō, what the U.S. later called "State Shintō" and which emphasized the divine origin of the Emperor. Hirohito's kinda-sorta "Humanity Declaration" after World War II meant that Buddhism was no longer suppressed, but after almost 80 years of suppression there was very little popular understanding or interest left.

The English words "religion" and "god" haven't had exact parallels in the Japanese language. Shintō is a national activity, something that Japanese people tend to do but without really believing much of anything about it. Asking about "the Japanese religion of Shintō" is like asking about the religious implications of Americans setting off fireworks on July 4th.

"So when you set off the fireworks, which deity are you worshiping?"

Um, it isn't a religious thing, we're just setting off fireworks.

"But it's so prevalent that it must be a religion. Does it honor the George Washington god?"

He wasn't a god.

"But the national capital building of the U.S. features a painting of 'The Apotheosis of Washington' under its central dome. 'Apotheosis' is a Greek word meaning that he is ascending into the heavens and becoming a god. This must be a religious activity."

Nope. Just loud noises and pretty lights.

"Maybe you're worshiping Ben Franklin? He would probably be into unregulated personal use of explosives and incendiary devices."

Look, it's just a thing we do, there's no profound meaning.

"What moral guidance does it provide? What is the cosmology? What is your personal relationship to the deity?"

....

Visitors to a Shintō shrine will shake a large rattle and then clap twice to awaken the deity. Then when Japanese people visit something that to me, the ignorant foreign visitor, is obviously a Buddhist temple, they act like it's a Shintō shrine and do the double clap.

Buddhist temples, especially in areas popular with tourists, sometimes have a hand-written sign in English saying "No clap — Buddhist!", with no corresponding explanation in Japanese. They have basically given up on the locals. They're telling foreign visitors not to imitate the inappropriately-behaving local people.

OK, back to this temple complex where actual religious activity goes on.

Moving further into the complex, here is the kondō or main hall.

To the right of the main hall is the Kaizandō or Founder's Hall, honoring the priest who founded Seiryū-ji.

I was surprised to learn how recently this temple complex was founded. Ryuko Oda, also known as Takahiro Oda, was born in 1914. He became a Shingon priest and founded Kōya-san Aomori Betsu-in, the first hall we saw above, in 1942. Then he founded Seiryū-ji as a temple complex around it in 1982. Everything is built to very traditional design, so you wouldn't immediately realize how recently it was built.

The English-language guide you pick up when you pay your admission says:

There is a saying that "If people have no Buddhism mercy in their minds, they will be disturbed; at the same time, if there is no Buddhism, the country will be devastated." Based on this saying, Japan has governed the people based on teachings of Buddhism. Good spirit, such as diligence, hard work, and the effort of the Japanese people has become a major driving force for the postwar recovery of Japan. However, the fact that recent Japanese have lack of religious mind is intolerable. It has made a futile society of a lot of desire, competition, and crime. And the disturbance of people's minds is obvious in Japan.

Ryuko Oda, the founder of Seiryū-ji temple (1914–1993) said, "The good spiritualism of the Japanese cherished by the instruction of Buddhism has disappeared. The main reason is that the economic supreme principle and the utilitarianism has become the main values since post-war time. In other words, the era has become 'More money, less peace of minds'." He thought that Japan could not recover without the true Buddhism teachings. So he wished to build the Great Buddha as its symbol.

That Great Buddha statue, the Shōwa Daibutsu, was built in 1984, and the Kondō or main temple hall was built in 1992.

Looking back to the main hall you can see the pagoda beyond it. Let's see the main hall first.

Where is there a Shintō-style rattle hanging in front of the entrance? That just encourages the inappropriate clapping. They probably got tired of explaining Japanese religion to confused Japanese visitors and simply added it.

A priest was worshiping in the main hall, I sneaked a picture anyway.

The main figure here is Dainichi Nyorai, originally known in Sanskrit as Mahāvairocana. This is the central deity or central manifestation of the Buddha in Esoteric Buddhism. Buddhist sects usually teach that full enlightenment requires many reincarnations over aeons of time. Shingon, on the other hand, teaches that someone can achieve enlightenment in one lifetime through the proper performance of philosophical training and rituals. The rituals involve body (mudra, gestures or signs), voice (mantra), and mind (philosophical ideas). It's sort of the Buddhist version of the debate over salvation by faith versus salvation by works.

As is often the case, there is a passageway making a circuit around the altar area. You walk the circuit in a clockwise direction, keeping the altar or devotional object on your right. Here, a sign saying "ROUTE" sent me in the correct direction. The circuit starts off the left side of the above picture, proceeding back a passage visible through the lattice on the left side of the altar area. It takes you to an area where the priest and monks prepare tea.

The middle section of the passage, directly behind the altar, has a reproduction of a famous painting at Kōya-san. It's "Descent of Amida and Heavenly Multitude" and the original is a National Treasure of Japan. Pure Land Buddhist belief says that Amida Buddha or Amitabha welcomes devotees to his paradise, the Western Pure Land, where they can achieve a perfect spiritual state. Paintings such as this one represent Amida Buddha accompanied by bodhisattvas descending to meet the faithful at the moment of death.

The Five-Storied Pagoda and the rock garden are nicely visible from the side porch of the main hall. The five stories represent the Five Elements of Buddhist cosmology. Remember what those are? Class? Anyone?

That's right: Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and Space, from bottom to top. On the previous page I said it wouldn't be on the test, but I didn't say that it wouldn't come up.

How to doablutions

There's a fountain where you perform ablutions, purifying yourself before continuing toward the Great Buddha. In April and May of 2023, because of COVID-19, dippers had been removed and many ablutions fountains were drained at both Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines. One year later, things were mostly returned to normal.

There are statues of Jizō along the right side of the path. Jizō, Kṣitigarbha in the original Sanskrit, is a bodhisattva typically depicted as a monk carrying a staff and a wish-fulfilling jewel. He vowed to instruct all beings in the era from the death of the historical Gautama Buddha until the arrival of Maitreya. He's one of the four principal bodhisattvas in East Asian Mahayana Buddhism. Jizō is regarded as the guardian of children and the patron deity of deceased children. Here, you can purchase a windmill in memory of a child and add it to the group beyond the statues.

[Failing to suppress the compulsion to point out the blatently Shintō symbolism of the rope over the waterfall]

There's a statue of Kannon, the bodhisattva of compassion. Known as Avalokiteśvara in the original Sanskrit, the Chinese called the figure Guanyin and the Japanese pronounce that as Kannon.

At this very recently founded temple complex, in the country with the world's greatest average longevity, the bodhisattva of compassion is described as possibly preventing or at least lessening the suffering of dementia for patients and their families.

The Daibutsu or the Great Buddha is further up the path. Like the main temple hall, it depicts the Dainichi Nyorai manifestation of the Buddha.

I had been puzzled by this being called the Shōwa Daibutsu. Why is it named for the reignal name of the Emperor usually referred to as Hirohito in the west?

Yes, I'm describing a Buddhist temple, so I'm criticizing government policies that are the opposite of compassionate.

Oh, that's right,

1926–1989 was the Shōwa Era,

the reign of the Emperor named Hirohito at birth

but now called (in Japan) the Shōwa Emperor.

Dates within that era may be referenced as the number

of years into it.

If we used that nomenclature in the U.S.:

"The 'Trickle-Down Economic Theory'

failed in Hoover 2–4

but was brought back in Reagan 1–8."

The founder of Seiryū-ji wanted to re-establish

Buddhist practice in post-World-War-II Japan,

and so "Shōwa Daibutsu" emphasizes that this

Great Buddha is of that period,

unlike much older Daibutsu in

Kamakura,

Nara,

and elsewhere.

This is cited as Japan's tallest bronze seated Buddha statue, 21.35 meters in height and weighing 220 tons. Other Great Buddha statues can be "largest" by other measures.

Having graduated from Purdue University and still living in West Lafayette, I am reminded of the Purdue marching band's large drum. The university is careful to brand it as the "World's Largest Drum" and keep its actual dimensions a secret. The University of Texas at Austin has an obviously larger drum, and the University of Missouri has one that's even bigger yet.

But those are just U.S. universities, in the minor leagues as large drums go. None of their drums come close to the traditional CheonGo drum of Simcheon-Meon, South Korea, which is five and a half meters in diameter, almost six meters tall, and weighs 7 tonnes.

But all of that is just to make fun of U.S. universities being silly. This is a seriously big statue of the Buddha. I was impressed.

You can enter the base beneath the Buddha's lotus-blossom seat. Put your shoes in a cabinet at the entrance, and enter a circular chamber where the six paths of reincarnation are illustrated.

Then, go upstairs. This takes you into an area within the lotus blossom seat, so the upper wall and ceiling are the interior of the textured bronze surface. Sutra quotes and small Buddha plaques cover the walls.

These pictures are from my visit on May 1st, when many trees were still blossoming.

Continuing along the path, I went down the hill past a cemetery.

Further along, there was a pool with a representation of the Buddha's footsteps, and a statue of Kūkai in the simple robe and round hat of a Buddhist pilgrim.

Return to Town

I had enjoyed seeing everything along the way and at the Seiryū-ji temple complex. Now it was time to head back to the center of Aomori. I needed the exercise, so I simply walked all the way back, a pleasant walk of almost seven kilometers along a flat route.

Along the way I passed a building that seemed at first to be an optical illusion. No, it really tapered to a point only about a meter thick, and probably wasn't more than two and a half meters thick at the "wide end".

Much of the ground floor was a plumbing supply shop, so I figured that it was mostly stacks of pipes slid into the pointed end of the building.

Onward from Aomori❯ By ferry across the strait to Hakodate, on Hokkaido

Other topics in Japan:

A Christian church doesn't claim that John the Apostle is in a box back behind the altar. Nor does this facility say that they have Kūkai's spirit contained. "Honor" and "venerate" are what both faiths really mean about the figure to which the structure is dedicated.