Tōkyō to Aomori

By Shinkansen from Tōkyō to Aomori

I was returning to Japan for another multi-week trip

extending from late April through much of May.

That schedule worked well for me.

It also meant that I would arrive immediately after the

crush of cherry blossom viewing,

and leave before the surge in foreign,

especially U.S.,

visitors.

The down side is that I would once again be arriving

at the beginning of Golden Week,

the busiest Japanese holiday period.

Well, it had worked out fine on previous trips.

Let's see if I can't make it work again.

Since my first independent trip to Japan

I had been intrigued by with the

kofun,

keyhole-shaped megalithic tombs dating from

the middle of the 3rd century CE

through the early 7th century.

On this, my fourth independent visit,

I planned to visit sites from the much earlier

Jōmon culture

that inhabited Japan from about 14,000 to 300 BCE.

I would fly into Tōkyō,

stay there for two nights,

and then travel north on the Shinkansen.

There were Jōmon sites around Aomori,

at the north end of Honshū, the largest island,

and more across the strait on Hokkaidō.

Google Maps dynamically generates the map when you load this page. Depending on what time it is in Japan, you may see buses by a different route instead of my 3.3-hour rail trip by Shinkansen from Tōkyō to Aomori.

Traveling During Golden Week

As a general rule, overseas flights are cheaper in the middle of the week. So, I would fly out of the east-central U.S. on a Wednesday. I live on the western edge of the Eastern Time Zone, at UTC-4 during the nonsense that is Daylight Savings Time. Japan is at UTC+9 year-round, The roughly 12.5-hour flight and the 13-hour time zone shift would have me landing in Tōkyō late on Thursday afternoon.

I had accurately anticipated being in pretty rough shape after the flight. I was not ready to go to Tōkyō Station on Thursday evening. I would go on Friday morning to buy my Shinkansen ticket for a Saturday late morning to mid-day departure.

I have issues with several aspects of Google's operations, but some of their services are impressive and extremely helpful. For example, Google Maps had told me that there was a Shinkansen run leaving Tōkyō Station at 1220 and arriving in Aomori at 1556. That was correct, and the cited price was accurate.

However, when I arrived at the Shinkansen ticket office at Tōkyō Station on Friday morning, the ticket agent shook her head, sucked air through her teeth, and regretfully informed me that the specific train was full, no seats were left.

"Ah, yes, it's Golden Week", I said, I had anticipated this and hopefully I could take a later train. She perked up and said "Yes, you could take a later train." I figured that as long as I got there before the last Shinkansen run of the evening, that would work out. She typed on her terminal and ran her finger down a column. "There is a later train, it leaves at 1228."

Whoa, what? The "later train" is only eight minutes later? "Mmmm, yes, eight minutes later", as if that would be a great inconvenience. In Japan, maybe. But where I live, on an Amtrak line connecting Chicago to East Coast cities from Washington through New York, there are only three trains per week in each direction. "Yes, please, give me a ticket on that later train." There was even a window seat available.

I bought my ticket, then took the Yamanote Line north to Ueno and walked to the Tōkyō National Museum to see items from the prehistoric cultures of Japan — the Jōmon people of about 14,000–300 BCE, the Yayoi people of about 300 BCE to 300 CE, and the Kofun period of 300–538 CE, defined as ending with the arrival of Buddhism from China via Korea.

Saturday morning I packed up and headed to Tōkyō Station. Yes, this was the start of Golden Week, it seemed that much of Japan was on the move. Below is the view on one of the multiple dual platforms for northbound Shinkansen trains — most of them pure Tōhoku Shinkansen trains running north on the main line, some of them coupled to Mini-Shinkansen car sets that would split off along the way onto the lines to Yamagata and Akita.

Notice the north-bound Shinkansen departures on the schedule board — platform #23 at left has departures at 12:00, my hoped-for 12:20, and 12:36; and platform #22 at right at 12:04, 12:12, and my train, at 12:28. Not all of them go all the way to Aomori, but many do. Several shops along the platform sold bentō box meals and drinks, and I picked up my lunch.

Below I have turned to look the opposite direction. The clock shows that it's 12:04. Yes, of course the clocks are precisely synchronized, it's really 12:04. The white train at left has just closed its doors and is starting to move. It's still listed as the next departure at the top of the list.

My train is the third one on the list at left, the はやぶさ or Hayabusa #377, leaving at 12:28.

Notice the green and orange stripes on the platform floor. Passengers for the next train line up between the green stripes, and those for the following train between the orange stripes.

When the next train pulls in and opens its doors, the queue of people between the green lines efficiently moves forward onto the train. Then the people between the orange lines shift over between the green stripes, and the next set of people line up between the orange stripes.

There was time to notice the following, but there wasn't time to get a picture:

- The train I had intended to take was Hayabusa #23, leaving at 12:20 and listed on the platform at right above.

- I instead took the slightly later train, Hayabusa #337, at 12:28 at left above.

- The next train north to Aomori after that left only another 16 minutes later, at 12:44.

Wow. Three trains departing for the northern end of Honshū within a span of 24 minutes, some of them continuing through the Seikan Tunnel under the Tsugaru Strait to the island of Hokkaidō

All Aboard!

Here's the futuristic Hayabusa on the Tōhoku Shinkansen. It's a 10-car E5 series Shinkansen train set. It runs at a top speed of 320 km/h, although the E5 design has operated at 400 km/h in test runs.

The doors open, we march in and find our seats, and the doors close within four to five minutes. This is the beginning of the run, and so that 4–5 minute stop is actually quite long as Shinkansen operation goes. Most station stops have the doors open for only a minute or two.

Off we go, north from Tōkyō Station to Ueno Station, where we will briefly stop to pick up more passengers. At that point the train will be completely full. Golden Week.

Tōkyō to Sendai

Japan is on the "Ring of Fire", it's an archipelago of volcanic islands. Much of it is rugged mountains. Only about 20% of the land is suitable for farming.

Therefore, almost all arable land is efficiently farmed. All at once we abruptly left the cityscape of Tōkyō for rice paddies.

And then, just as abruptly, into Utsunomiya:

And once again, a sudden transition from city to farmland.

Cities have very distinct boundaries in Japan. In the U.S. I'm used to it taking a long time to gradually get out of a city, as the settlement density very slowly decreases. Buildings become smaller and are placed further apart, and you drive a significant distance through that slow transition.

Japan's largest crop is rice. They produced 10.4 millions tons of it in 2022, keeping Japan around number 13 world-wide.

Soy beans are also important, used for miso, soy sauce, and other products.

As for corn, known as maize, dominant where I'm from? It's extremely rare in Japan. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations:

| Country | Crop | Tonnes | Hectares |

| Japan | Rice | 103,639,000 | 1,497,500 |

| Soy beans | 242,800 | 151,600 | |

| Maize/Corn | 162 | 63 | |

| U.S.A. | Rice | 7,274,170 | 878,990 |

| Soy beans | 116,377,000 | 34,939,320 | |

| Maize/Corn | 348,750,930 | 32,054,280 |

Bentō On Board

I got out the bentō I had purchased at Tōkyō Station.

It was a two-layer bentō, rice in one part and an assortment of grilled fish, steamed vegetables, and pickled vegetables in the other.

Behold the so-kawaii carrot.

When I traveled from Tokyo to Yamadera on an earlier trip, it was on a train that was an E3 series Mini-Shinkansen coupled to an E5 series Shinkansen. The combined train followed this route as far as Fukushima, where the Mini-Shinkansen was disconnected and continued on its own, first winding up into the mountains to the west, then turning north to Yamagata.

This trip was an E5 series end to end, it stopped for only 1–2 minutes at each station.

Sendai to Aomori

Many people got off the train at Sendai, we went from well over 90% full to maybe 35–40% full.

On we went, passing through Morioka. Snow was appearing on the mountains.

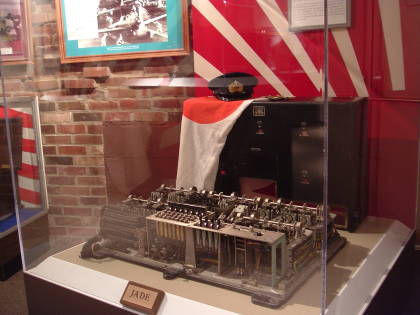

We continued north, stopping at Hachinoe. That was very close to Misawa Air Base, where I had been to teach a Linux server class in 2003. Misawa is a joint U.S.–Japan air base used by USAF, USN, and JASDF, and it's also a major SIGINT facility. That had been a teaching trip in which I couldn't stay in Japan on my own due to time constraints. And, with it being at least partially a U.S. military base, the U.S. Department of Defense pays Halliburton and other contractors to make it as much as possible like a base in the former Confederacy. American fast food outlets, and country music and right-wing talk shows on the low-power radio station.

The Last Hop by Local Train

I only know a few words of Japanese. One of those is shin, meaning "new". It's part of "Shinkansen", meaning "new main line". Compared to what I see at home, the Shinkansen is beyond merely new, it operates on some science-fictional level. But yeah, the name means it's "new". And then some.

Shin-Aomori Station is thus the New Aomori Station. It's a relatively new station outside the city center where the Shinkansen stops on its way past Aomori.

The Shinkansen I was riding terminated at Shin-Aomori Station. I got off and followed the crowd that was hustling through the gates from the Shinkansen section toward a platform for a local train. They clearly knew what they were doing, and it was very safe to assume that I did not. I should follow them!

Yes, hurry down the corridor, feed in your tickets and pass out through the Shinkansen gates (while they retain the Shinkansen-specific piece of your collection of ticket components), then down an escalator to an open platform and onto a local train that was about to depart.

This was a train on the Ōu Line. It joins Aomori Station at the center of the city to Shin-Aomori Station and its Shinkansen service, and beyond to Akita, Yamagata, and Fukushima.

It was a short ride of only about six minutes over four kilometers to Aomori Station.

Following the crowd off the local train, up the escalators and over the tracks, I could look down on the local train that had been the last hop to Aomori.

From here I had a trek of about 1.5 kilometers through downtown Aomori, from the station to the Smile Hotel where I had a room reserved through booking.com.

The room was a little reminiscent of where Korben Dallas lived in The Fifth Element. Just a little — no flying ramen shops paused at my window. Also, the bed, bath, and various storage compartments did not slide out of the walls. But it packed in everything I needed, and space was tight and I had to walk sideways through much of it. (There will be more on a five-element cosmology on the way to the Jōmon site on a later page.)

You entered from the hall into a narrow passage between the bathroom at left and the right wall of the room. They provided a yukata or lightweight kimono for lounging. Hanging on the wall, it was a minor obstacle. The bed filled the room from bathroom to window. A desk along the right wall held a TV, and there was a mini refrigerator in the cabinet below.

The bathroom had a short but deep tub, so you could stand and shower and then fill a hot soak.

Exploring Aomori

I would stay there while I experienced the Aomori Spring Festival, went to the Jōmon settlement of the Sannai Maruyama Iseki site, and visited the Shōwa Daibutsu large bronze seated Buddha statue and associated temple complex.

First, though, a little exploration of Aomori itself. The waterfront was big on triangles. A building like a two-dimensional pyramid housed some souvenir shops and a ramen and curry restaurant on the ground floor. City and prefectural offices were above.

Beyond it was the triangle-supported Aomori Bay Bridge.

Cunard is still a luxury passenger ship line, and there still is a MS Queen Elizabeth. The current one can carry just over 2,000 passengers, and was visiting Aomori. 294 m length, 32.37 m beam, and 16 decks.

The Hakkōda-maru is a museum ship explaining ferry history. Until the Seikan Tunnel, the world's longest undersea tunnel, opened in 1988, travel to and from Hokkaidō was by ferry or air. The rail line from Tōkyō terminated at Aomori Station and there was a short transfer to the ferry terminal.

I was in Aomori at the end of April, snow remained on the mountains to the south.

Most of the pedestrians signals were of the older design, with a blue lens on the Walk light.

Honcho Ramen was not too far from where I stayed, and I went there two nights.

They had curry ramen, popular in that area. This is based on Japanese curry, a salty curry gravy unlike what you find at Indian, Thai, and Vietnamese restaurants.

Another excellent ramen place was just around the block from my hotel, Cyuka Shoba Gin.

A Rainy Day

On one day it rained for most of the day. I went to Utou Jinja, a Shintō shrine only three blocks from where I was staying.

As usual, several auxiliary shrines enshrine or host various kami or spirits or deities.

The three-legged crow is a mythological creature known to various East Asian cultures at least since the middle of the fifth millennium BCE.

Yatagarasu is a specific huge three-legged crow that Shintō says served as a guide for Jimmu, the first Emperor of Japan, on his journey to the region that would become Yamato.

This one, however, has two legs and far too many eyes.

In his novella At the Mountains of Madness, H. P. Lovecraft described a shoggoth as "... a terrible, indescribable thing vaster than any subway train—a shapeless congeries of protoplasmic bubbles, faintly self-luminous, and with myriads of temporary eyes forming and un-forming as pustules of greenish light ..."

The haiden or oratory, the largest part of the main shrine, was fairly ordinary.

What was more interesting was the main shrine's honden, the most sacred structure of a shrine. It's behind the haiden, inaccessible to worshipers as it's strictly for the use of the enshrined kami.

A small bridge led across another carp-filled waterway to a tiny shrine on a tiny island.

It was a dark, cool, and wet day, but that just made the shrine and other places I saw more atmospheric.

At the end of the day I was ready for a hot soak in the short tub, and then a steaming bowl of ramen at Cyuka Shoba Gin.

Other topics in Japan:

The future is here — it's just not evenly distributed.

— William Gibson