Kagoshima

Exploring Kagoshima City

I had a two-day transit pass that I could use to

get to and from the Sakurajima ferry terminal,

and to ride the bus part-way up

the volcanic cone of Sakurajima.

I also used it to explore Kagoshima.

Above is a city tram and, in the background, a bus.

Small portion of 1:1,000,000 Operational Navigation Chart TPC H-13 from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. Elevations and tower heights are in feet.

Wandering Around Kagoshima

I was reminded again of how Japan feels like the future. And that's without getting close to the Shinkansen train system, which is straight out of science fiction.

My conclusion is that it isn't really the future, Japan has a present that the U.S. turned down. Clean cities with efficient and reliable public transport. No need for cars as it's easy to walk places. No litter and almost no crime. Almost no people living on the sidewalks in desperate need of mental health care.

Here's a bright red mailbox with the post logo that looks a little like テ, the katakana for te. (Although that is where the 〒 symbol came from.)

A reconstructed historic stone lantern stands across the street. Beyond that, an extremely narrow building with an exterior circular staircase, a fairly common design in Japan.

Turning around, I saw a small Shintō shrine near the mailbox. A torii or gate with a hemp rope and white paper shide zigzag strips, so it's definitely Shintō.

This is from a trip in May 2023, when the ablutions tanks at many shrines and temples were still drained because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But this one was back in operation.

To The Tram

I continued up the street and around the corner. Notice what looks like a yellow stripe running up the center of the sidewalk.

It's made of ceramic tiles with raised stripes. It's there to allow people with low to no vision to navigate on their own. When two sidewalks cross or form a T, or when there's a street crossing, a special tile of round dots indicates the intersection.

Then, the curb cuts at street crossings have a distinctive tile patterns, and a stripe of the linear ones guides people across the street.

The Yamakataya department store stretches for a block. All this was built after World War II. A B-29 raid on 16–17 June 1945 destroyed 44% of the built-up area of Kagoshima. The U.S. had run out of bombing targets in the largest cities, and had shifted the missions to target smaller cities.

The tram line runs down the center of this main street. The median of the street is planted in grass. With grass instead of asphalt, it's a little less heat in the summer, and some rainwater is directly absorbed into the ground instead of being channeled into a drainage system and dumped into the bay.

There's grass and also flowers at the tram stop. A covered shopping arcade goes through the middle of the block across the street.

Here comes the tram.

Why Are Power Lines So Prominent In Anime?

Because anime is from Japan, where power lines are very prominent.

They're meticulously installed — parallel, not overly drooping, carefully interconnected. In Japan you're constantly walking through a display of how to install power lines.

Electrical power is at 50 Hz in Tōkyō and on to the northeast, through northern Honshū and Hokkaido.

Southwest of Tōkyō, down through Kyūshū, it's 60 Hz.

It's because of history. Individual cities built independent electrical power systems. Tōkyō and surrounding cities bought 50 Hz equipment from Germany's AEG. Osaka's power company bought 60 Hz equipment from General Electric, in the U.S. Electrical service spread out from there.

Japan's rugged terrain meant that regions were electrically isolated from each other. The idea of a national grid didn't come along until there was already an enormous investment in the mixed systems.

Now there's a national grid system with limited frequency-converting interconnections between the 50 Hz northeast and the 60 Hz southwest. That became an issue when the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami shut down the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. The southwestern grid had a surplus of energy, but there wasn't enough interconnection capacity to convert much to flow between the two grids.

Replacing half of Japan's electrical power system would be an enormous project. Building adequate frequency-converting interfaces wouldn't be quite as large of a project, but it still would be awfully expensive.

Ku-ri-ni-n-gu, it says. "Cleaning".

More Shrines and Temples

Terukuni Shrine is in a park near the city center. It's officially considered to be the dwelling place of the kami of Shimazu Nariakira, who was the local daimyō or feudal lord in 1851–1858.

Early in the Meiji period, a few shrines were designated for venerating loyal subjects of the newly powerful Emperor. Shimazu was the subject of the first daguerreotype photograph created in Japan, and his portrait became an object of worship at the shrine. Then it went missing for over a century, and was rediscovered in a warehouse in 1975. So now it's also the first photograph designated an Important Cultural Property by the national government.

This Buddhist temple looks rather businesslike. It's still obviously Buddhist, with the anthropomorphic statues and the sōrin spire with multiple rings.

There are very few Christians in Japan. Most of them are in Nagasaki, the only city the Shōgun allowed Europeans to visit for several centuries.

Francis Xavier's party of Jesuits first landed here in Kagoshima in August, 1549. There's a statue of him along the waterfront north of the Sakurajima ferry terminal.

Covered Shopping Arcades

A picture above showed the large Yamakataya department store, which is on the edge of the Tenmonkan shopping district. An area of about 5×6 blocks has most of the streets converted to covered shopping arcades.

It's very nice. You can arrive by public transport and walk from shop to shop. Stores sell a wide range of goods. You can stop in numerous restaurants, coffee shops, and ice cream shops. Motor vehicles can still make deliveries.

This is more of the present the U.S. chose not to have. Department stores were shut down in the U.S. as retail business moved out to the perimeters of cities, to shopping malls surrounded by enormous asphalt parking lots. Now those malls are largely deserted. Mall businesses still operating mostly offer non-essential junk like novelty printed T-shirts, and infrequently used services like formal wear rental shops.

If you want to buy a book, some socks, some batteries, and a bottle of shampoo, you could buy all that during a short stroll through a covered arcade in a Japanese city.

In the U.S., you would get in your car and drive to Walmart, run by a family of billionaires with a large percentage of the staff relying on SNAP (formerly called Food Stamps) to survive. And of course Walmart's offering of books is mostly limited to Inspirational Literature, to the extent that it's actually literature. Or inspirational. Romance novels set among the Amish. Country musicians' compilations of "Christian recipes". And so on.

A bewildering array of capsule machines offers small goods, gifts and toys and charms packaged in plastic eggs, for ¥ 100–500.

Subterranean Yatai

Kagoshima-Chūō Station is the main rail terminal in the city. It's the southern end of the Kyūshū Shinkansen line, the southern tip of the entire Shinkansen system. It used to take at least four hours to travel by train from Kagoshima to Hakata, the Fukuoka station. Now the Shinkansen covers that distance in an hour and twenty minutes.

I had read that there was an underground passage with yatai, informal ramen stands like those lining the canals in Fukuoka. I wandered around for a while before discovering it in the basement of another tall shopping building, just across the main street from the tram stop and the main station.

I went to one offering ramen in the local style of the Amami island group in the northern Ryukyu Islands.

I think I successfully communicated to my host that I had gotten Okinawa's Orion beer, this place's standard drink, at a ramen place in the East Village in Manhattan. English on the label, "From Okinawa to the World", it says.

Kagoshima and the Modernization of Japan

During the Tokugawa Shōgunate of 1603–1868, the Emperor was cloistered in Kyōto, carrying out Shintō rituals. Japan was ruled by the Shōgun, the military warlord. He ruled from Edo, what later became Tōkyō. It was the Edo Period.

That left the island of Kyūshū far from the centers of power. The Shōgun had outlawed Christianity and expelled missionaries. He had allowed Dutch traders to continue operating, but only from a small island within the Nagasaki harbor. Chinese trading ships weren't as strictly controlled, but they were largely restricted to landing in Nagasaki.

Europeans couldn't land anywhere else in Japan, and Japanese people were not allowed to travel outside the country except on missions specifically approved by the central government.

Japan was cut off, and largely unaware of the outside world. Kyūshū was the closest thing to a very limited exception to those rules.

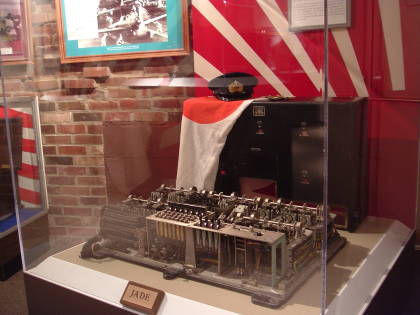

Matthew Perry's U.S. Navy expeditions to Edo Harbor in 1852–1854 forced the Shōgun to open Japan to U.S. ships, which in turn led to the end of confidence in the Shōgun. The Emperor returned to power, with a renewed emphasis on his divine nature.

Kagoshima had a prominent role in the civil wars between various pro-shōgunate factions and the Emperor's forces. Several Kagoshima men who had trained as samurai transitioned to prominent business and government roles. One was Ōkubo Toshimichi, depicted by this statue with his large mutton-chop sideburns. It was an epic time for facial hair.

He had been involved in negotiating the settlements associated with the British naval bombardment of Kagoshima in August, 1863. After the Meiji Restoration of 1867–1868, he established the Home Office of the new national government, became Home Secretary, and was the most powerful man in government for a while.

People had tired of his autocratic ways by 1878. One day, on his way to work, a group of former samurai assassinated him.

A group of statues at the main railway station depicts the Satsuma Students, a group of 15 from the Satsuma Domain, based in Kagoshima, plus one each from Nagasaki and Tosa.

In 1865 the Scottish businessman Thomas Glover, seeing the untapped market of Japan while building up his business operations in Nagasaki, helped elements of the Satsuma Domain send the group of students to London. They had to make it seem as if they were going to Koshikijima, a nearby group of islands in the East China Sea. Instead, they sailed to Singapore, and onward from there to London.

They studied at University College London, at the time one of the few schools open to students of all religions, and some of them went on to study at Oxford and Cambridge. Beyond their course work, they were learning about the outside world, its businesses, and its governments.

The students went on to prominent roles in the national government and in industry. Glover was meanwhile selling arms to the Meiji government, building two of the first warships in the Imperial Japanese Navy, and building Japan's first dry dock facility, railway, and coal mine. His shipbuilding company became the Mitsubishi Corporation.

And, of course, he continued growing out his facial hair. He also helped to found the Japan Brewery Company, which became the Kirin Brewery Company, Ltd. A legend lives on saying that the creature featured on Kirin bottles is a tribute to Glover and his elaborate moustache. It was, as I've already pointed out, an epic time for facial hair.

From Kagoshima City I traveled by Shinkansen north to Kitakyūshū and then southeast to Oita on an express train.

Other topics in Japan:

Yes, it's just a little like テ, which instead has a curved leg. My goal was to be able to pronounce things written in katakana and hiragana and not to perfect my penmanship.