Kamezuka Kofun, a Prehistoric Burial Mound

From One Kofun to Another, Past the Waterfront and a Spare Sarcophagus

What's akofun?

I was staying in Ōita

and had visited the Tsukiyama kofun,

a prehistoric megalithic tomb.

Now I was headed for an even larger one,

the Kamezuka kofun.

It was a walk of a little over seven and a half kilometers.

I passed some small temples and shrines,

one with what purports to be a historically significant

sarcophagus.

I chose a route that took me along the waterfront,

past a marina with many boats.

To the Waterfront

I had followed Highway 197 west from Tsukiyama kofun and the adjacent Kanzaki Hachiman Shrine. The broad paved walkway dwindled to a narrow shoulder, and I was glad to reach the turn onto a narrow side road leading toward the waterfront. I walked through a residential area and soon approached Enmei-ji, a Buddhist temple. Several large cranes were visible in the distance, beyond the temple's cemetery.

Hiyoshibaru is an industrial artificial island. The narrow channel between it and the mainland hosts a long marina, with many of the boats used for fishing, both professionally and for recreation.

Of course there are gigantic power lines, this is Japan!

West of Hiyoshibaru the water opens out into Beppu Bay.

Crossing the Nyu River, I looked back to the east.

There were dredging cranes on barges and other things I don't see at home.

I followed a footpath along the west bank of the river. Google Maps on my phone showed a grey marker with a pair of human silhouettes, indicating a public restroom in a small park. Just beyond that, a green marker with a three-dot triangle. It was something historic! The explanation was entirely in Japanese, of course, so I checked it out.

The historic landmark was a Shintō shrine at 1 Chome-12 Onose.

A sidewalk leads from the street, under the torii or gate to the shrine. The historical designation comes from the content of the small building behind and to the side of the shrine.

The heavy hemp rope with hemp tassels and shide or white paper zig-zags marks this as specifically Shintō.

The object of interest lies inside.

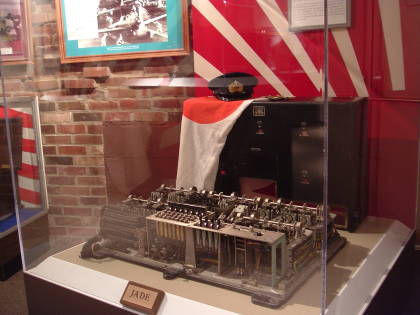

Thanks to Google Translate applied to my picture of the all-Japanese explanatory sign, and the websites of the Ōita Cultural Properties Division and the Ōita Prefecture Education Agency Cultural Division, I could learn that this was the Ōnose sarcophagus.

It's a well-preserved sarcophagus 2.5 meters long, one meter wide, and one meter tall. Both the coffin body and the lid are carved from volcanic tuff.

Ōita is a port, as it was back when this was the domain of Amabe Kaifu. The coffin is shaped like the hull of a ship, referencing the Amabe clan's sea power, while the lid is shaped like the roof of a house. Cylindrical protrusions on the lid would be used to attach ropes to lift it. Its style indicates that it dates from the mid to late 5th century CE.

The historical details remain vague. It is thought that the sarcophagus was brought here during the Meiji Period, after the Emperor had been restored to divine status and full power in 1868.

However... This is a fiberglass replica of the coffin. The actual Ōnose sarcophagus has been relocated to the museum at the Kamezuka kofun.

The shrine is in two structures connected by a wooden passageway.

Looking in through the main entrance, I could see through that passageway to the honden, the area the deity is thought to inhabit.

Well, it was still interesting to see. I continued south along the river, under the low bridges carrying the rail line and the highway.

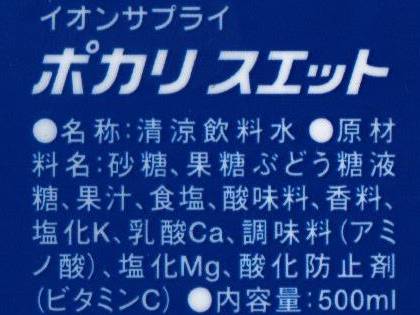

I stopped at a 7-11 and got a Pocari Sweat to drink. 7-11 is based in Japan, they have locations everywhere. Then it was a short walk south, and then around and up the hill to the Kamezuka kofun.

Kamezuka — So That's What A New Kofun Looks Like

Imperial kofunaround Nara

I had seen several kofun around Nara during my first independent trip to Japan. They are officially considered to be the tombs of early Emperors, many of whom are entirely legendary. But fictional purported inhabitant or not, scientific investigation has always been forbidden.

Since then, I've seen some non-Imperial and thus approachable kofun like one up north in Aizu-Wakamatsu, in southern Tōhoku, and the Tsukiyama one I had visited earlier this day.

This one, however, was the first I saw that had been restored to what is thought to be its original appearance.

In the morning I had seen a much smaller remnant of the fukiishi, small, rounded, white-colored stones collected from riverbeds and placed as an external layer over a kofun.

It's thought that the outer stone layer served two purposes — to protect the earthen structure from erosion, and to make it visually striking. This kofun is on a hilltop near the coast. With surrounding trees cut down, it would be visible for a significant distance out to sea in the Hōyo Strait.

The Kamezuka kofun has the most common shape, that of a keyhole, 116 meters long overall. The far end in the below view is a truncated cone, ten meters tall. A lower wedge-shaped section tapers out from that. The wedge has three tiers, reaching a little over half the conical section's height. This is the largest kofun in the prefecture.

An explanatory placard has a diagram showing the keyhole shape. It also depicts the images of ships on the haniwa, the barrel-shaped clay objects outlining the kofun. More funerary references to the local clan's naval strength.

Now, as for the depicted clay objects....

Jōmon, Yayoi, and Haniwa

The Jōmon culture developed around 14,000 BCE from the paleolithic hunters who had walked south from extreme eastern Siberia when sea level was much lower and the Japanese archipelago was connected to the mainland to its north.

During the last several centuries of the Jōmon culture, about 1000–700 BCE, they developed what are now called shakaki-dogū, or "snow goggle clay figures".

The Yayoi people began arriving from the Korean peninsular around 1000 BCE. They brought the Japonic language, wet-rice agriculture, and kami worship forming the original core of Japanese culture.

The Yayoi people began building these monumental kofun around 300 CE, and continued to around 700.

The Jōmon figures have faces similar to clay masks found along the Amur river in Northeast Asia. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York says, "The most arresting aspect of these figurines is their large bisected coffeebean-shaped eyes. While the true meaning of this convention remains unknown, the eyes are often likened to the snow goggles worn by the Inuit of North America." And also, "The distinctive eyes of this figure, which crowd out the mouth, nose, and ears, were once thought by scholars to represent a kind of snow goggles common to other communities of the far north, such as the indigenous peoples of Siberia and the Inuit of Canada, but modern scholarship tends to believe that they reflect the Jōmon people’s emphasis on the eyes, which may have a kind of religious significance."

Late to Final Jōmon (1000–300 BCE) figure in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Jōmon (1000–400 BCE) figure in the collection of the National Museum in Tōkyō.

Final Jōmon (1000–300 BCE) or later figure in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The emphasis on the pointed breasts and generous hips of these figures suggests that they functioned as fertility symbols.

We've seen this look in characters from Luc Besson films based on bandes dessinées.

The Yayoi people who had crossed from the Korean peninsula became the dominant culture. When they began building kofun tombs around 300 CE, they included haniwa, terracotta clay figures. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York describes object 1975.268.414: in their collection, a haniwa figure, as:

The earliest haniwa, dating to the late third century A.D., were simple clay cylinders. Houses and animals as well as ceremonial and other objects appeared in the late fourth century, while figural haniwa were created in the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries. [...] Haniwa were placed at the top of the burial mound, in the center, along the edges, and at the entrance of the burial chamber of enormous tombs constructed for the ruling elite during the Tumulus, or Kofun (ca. 200–600), period.

These figures are in the National Museum in Ueno Park in Tōkyō. They are very unlike the earlier Jōmon figures.

Some haniwa depict animals or structures.

Other haniwa are cylinders.

Continuing up the Kofun

The wedge section is seven meters tall. A staircase of gravel and logs leads up onto it.

This kofun was built in the early 5th century CE. Replica cylindrical haniwa line some edges of the levels.

Kofun continued to be built into the early 7th century CE. But by the early 6th century the fukiishi and haniwa were seldom added. No light-colored rock coat, no clay cylinders or figures.

Another set of stairsteps led up onto the top of the truncated cone. There's a large stone coffin in the center of the top.

The coffin is 3.2 meters long, 1.1 meters wide, and 90 cm deep, within a grave area nine by seven meters.

The coffin is made from slabs of local chlorite schist. The name schist comes from σχίζειν, meaning "to split", the way these panels were formed. The main compartment was for the body, grave goods were placed in the small compartment.

A placard at the top shows that there was a second, later burial. A smaller coffin was placed parallel to the large one at the center.

Both graves were robbed in antiquity. What remained of the grave goods were fragments of armor and iron swords, comma-shaped jade beads called magatama, and small beads made from jasper and glass. The amount spilled or left behind by the grave robbers indicates that there was a lot to start with.

There's a view over the Nyu River and on out to sea, today including the industry on Hiyoshibaru.

Local legend says that this is the grave of Amabe no Kimi, the King of Amabe. The early 8th century Nihon Shoki mentions a Kingdom of Amabe existing in this area.

Below, looking inland from the top of the kofun, you see the museum in the round-topped metal structure.

A path leads around the large kofun past other sights of interest.

The sign by this relocated tomb says, according to Google Translate for images:

Yayoi period sarcophagus tomb

This sarcophagus was unearthed during an excavation survey

for buried cultural properties conducted in 2010

in conjunction with the renovation of

the Sakano City Elementary School building.

Since it remained in good condition,

it was moved to a corner of Kamezuka Kofun Park

and restored.

The sarcophagus is constructed from

16 crystalline schist stones.

When it was discovered, it was covered with six stone lids,

and Yayoi pottery pots and pot stands were excavated

from around the sarcophagus.

Don't wander into the bamboo, there are poisonous snakes.

Kokamezuka Tumulus

There's a bonus kofun here! Just below the north end of the main kofun, toward the sea, is a smaller one built about 50 years later.

This is Kokamezuka kofun. A placard at ground level explains it.

Picture 143858, The photo at the upper right of the placard shows the rammed earth layer. The text says:

Kokamezuka Tumulus

This is a small-sized keyhole-shaped tumulus that was built

in the late 5th century,

about half a century after the Kamezuka tumulus.

Approximately 25m of the total length of

approximately 35m occupies the rear circular part.

The two-tiered mound was constructed by carving out

the ground in the first tier,

and using a method called rammed earth,

in which the second tier was alternately compacted with

different types of soil.

The roofing stones have not been laid yet.

Based on the condition of the tomb,

it seems that a large hollowed-out sarcophagus

was placed in the main body of the center of the rear circle,

and is made of tuff,

with the "Ounose sarcophagus"

(designated tangible cultural property of the city)

as a reference example.

A hollow-shaped sarcophagus is installed as a replica.

This burial mound is valuable as evidence of the period

when the power of the Kaifu region gradually weakened.

I walked back downhill from the kofun, crossed over the river, and continued a short distance east to the Sakanoichi train station. I had a short wait, then caught a train to the main Ōita Station.

I was headed toward the Furumiya tomb, as I had one more prehistoric tomb to find today.

Other topics in Japan: