Shintō in Japan

Shintō Practice Today

A Shintō shrine is a jinja,

a dwelling for the kami, the spirit or spirits

enshrined there.

Shrine names end with -jinja

or -jingū

or -gū.

You approach a shrine through a torii,

a gate made from two upright columns and two crossbeams.

A torii marks a boundary where you pass into

sacred space.

Or, multiple divisions of increasing sacredness,

as some shrines are reached through a series of several gates.

Here's an example at Kiyotaka Inari shrine in

Kōyasan.

The path leads up the hillside through dozens of torii, taking you to an open area in front of the shrine. Then there is one last torii leading into the building. Shrines often have a fountain with ladles to clean your hands and mouth before entering. However, there isn't one at this small shrine.

As you approach the interior, there's a rope that you shake to rattle a bell at its top. Then clap your hands twice. As for the bell or rattle and the kashiwade, the double clap, some say that it's to summon and show gratitude to the kami. Others say that it's to ward off evil spirits. Again, there's no single consistent explanation. It means what people think it means.

The clap is quite old, a holdover from Japanese prehistory. A Chinese text from the 3rd century CE reported that the Wa, the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese term for Japan and its people, clapped their hands during worship. This was five centuries before the Kojiki (or Records of Ancient Matters) and Nihon Shoki (or Chronicles of Japan) were written down, codifying Shintō practice.

There's a small offering box, where a coin with a hole is considered more auspicious. So, ¥5 or ¥50. There is often a table where you can leave food or drink for the kami. When the kami doesn't consume the food or drink, it goes to the keeper of the shrine.

There are often two guardian statues or kitsune. Here they are foxes wearing red bibs. Foxes are believed to have magical powers as they are messengers of Inari, the deity of good harvest. Fox-messengers are common shrine guardian figures. They are often dressed in red votive bibs.

Often the guardians at Shintō shrines are actually Buddhist guardian deities, the Niō. The one at your left usually has an open mouth, while the one at your right has a closed mouth.

That's another Buddhist feature. They're pronouncing the Sanskrit letters अ or A, then म or MA, forming the sacred syllable ॐ or Aum.

Aum is the sacred sound of Hinduism. But it is used as a mantra in Buddhist, Jain, and Sikh practice.

The actual dwelling for a kami here in the inner chamber is a miniature shrine. It stands just a little taller than me. It has a miniature rope and bell above its entrance.

The zigzag streamer is a shide. They are made from paper, hemp fibre, or other material. A pair of shide streamers hang on a wooden wand called a gohei or onbe or heisoku. A popular ritual involves a Shintō priest waving this "lightning wand" to bless a person or object. It might be used to bless or ritually clean a newly purchased automobile or property.

The shide can represent the enshrined and invisible kami, and so it may be the focus of devotion. A twisted straw rope or shimenawa may hold several shide.

Spirited Away is filled with Shintō imagery and concepts.

Here is a bundle of many shide at Tōshō-gū, a shrine at the tomb of Tokugawa Ieyasu at Nikkō.

Palanquins or portable shrines called mikoshi carry the shintai, the "god-body", the central totemic object normally kept in the most sacred area of a shrine. Or, to use the honorifics, the o-mikoshi or divine palanquin carries the go-shintai or sacred god-body.

The shintai are not themselves part of the kami or spirit of the shrine. They are temporary repositories which make the kami accessible to human beings for worship. They are also yorishiro, objects that are capable of attracting and, in some sense, capturing kami so they can be "enshrined" or housed within the shrine.

The omikoshi are used to carry the goshintai on a tour of the community at a matsuri or religious festival, or to move it to a new shrine location, or to capture a kami somewhere and transport it to be enshrined at a newly built facility. The omikoshi physically protects the goshintai and hides it from sight.

The first picture below is at Tōshō-gū, a shrine complex at the tomb of Tokugawa Ieyasu at Nikkō.

The picture above is at a small temporary shrine along a side street in the Asakusa district of Tōkyō. Below we see the priests preparing, then conducting a ceremony at this temporary shrine. The group then walked together to a permanent location two blocks away.

When a child is born, the local shrine adds them to their record as a "family child". After their death this ujiko becomes a "family kami" or "family spirit". The name is added regardless of personal or family wishes. It is not intended as a means of imposing Shintō belief on an unwilling individual, but to indicate a sign of being welcomed by the local kami.

Tō-ji

The shrine below is at Tō-ji in Kyōto. Notice the outer torii, the bell rope and metal donation box, the stone guardian koma-inu or lion-dogs with open mouth at left and closed mouth at right, and the offerings of sake and candy.

Also notice the shimenawa, the rice straw or hemp rope used for ritual purification and to ward off evil spirits. Shimenawa can bound a sacred space such as a Shintō shrine like this one.

Taimatsuden Inari shrine

The small Taimatsuden Inari shrine in Kyōto, seen below, is associated with a larger shrine. This one is in a small lot beside the end of a bridge over Kamo-gawa, the Kamo River. It actually has two shrines.

In addition to the two Shintō shrines, this complex also has a small Buddhist shrine. It's a small structure on top of the block with the swastika, next to the ablutions fountain. Large Buddhist structures where services are held are called temples. This, however, is just a shrine in the Buddhist sense, with a small statue of a Bodhisattva or other manifestation of the Buddha.

Small Shrines

Small shrines are everywhere in Japan. Here is a pair, Buddhist on the left and Shintō on the right. This is along the Takase Canal in Kyōto. A small Shintō shrine is called a hokara.

The Buddhist one has swastikas on the base and in the frame above its doorway. It has a small statue of a manifestation of the Buddha behind the wooden grill. The Shintō shrine has no image.

Okazaki Shrine

Okazaki shrine in Kyōto was associated with the Emperor and Empress when it was founded in 1178 CE. The Emperor called for its establishment to protect the Imperial Court and expel evil from the four cardinal directions. Because of that, it is believed to house the god and goddess of dispelling evil related to the compass points. Because the Empress gave it a ritual offering after giving birth, it is also believed to house the god and goddess of easy childbirth.

Rabbits are considered to be the servants of the evil-dispelling deities. Because rabbits reproduce prolifically, and also because of the connection with the Empress's childbirth, this shrine has become quite popular with people wishing for children. They write their wishes for future births, or thanks for successful births, on ema, votive tablets or prayer plaques.

Rabbits flank the approach to one of the shrines along with the koma-inu or lion-dogs. All of them follow the Buddhist pattern of open mouth on the left, closed on the right.

Au- ...

अ ...

... -mmm

... म

A rabbit presides over the basin in the hand-washing shelter, which is lined with votive plaques. Shintō refers to the ceremonial purification rite as temizu, the water-filled reservoir as mizuya or chōzubachi, and the small shelter or pavilion as the chōzuya or temizuya.

Larger shrine complexes like this one sell charms or omamori, prayer plaques or ema, and other material.

When I was in Japan on this trip I heard far more Russian than English spoken by foreign visitors. But I saw more English wishes written on votive plaques than Russian. So, at least from a Bayesian point of view, English speakers are far more likely than Russian speakers to write wishes on votive plaques.

Shintō and the Emperor in Prehistory

The Kojiki and Nihon Shoki of 711-720 CE were only partially historical. They largely contain the mythology of the Emperor's ancestry. All the figures listed before Emperor Ōjin of the late 3rd century CD are legendary. Emperor Ankō of the 5th century was the earliest historical ruler of at least a part of Japan, and he appeared as the 20th Emperor in the legendary lists. Up to that time, Japan had been entirely clan-based.

The Yamato group of powerful clans had organized by the late 400s CE. They were each headed by a patriarch called the Uji-no-kami who performed rites honoring the clan's kami or spirit. The clans wielded power on a local to regional scale only.

One clan became dominant over the centuries. Its ruler was known within Japan as Yamato-ōkimi, the Grand King of Yamato. Chinese chroniclers called him Wakoku-ō, the King of Wa. As they came to rule larger areas of Japan they become increasingly aristocratic and militaristic. The supposed Japanese Emperor still petitioned China's leadership for the use of the title Ame-no-shita shiroshimesu ōkimi or Sumera no mikoto, the "Grand King Who Rules All Under Heaven".

In the 600s the Emperor came to be called Tennō, the Heavenly Sovereign, the title still used today.

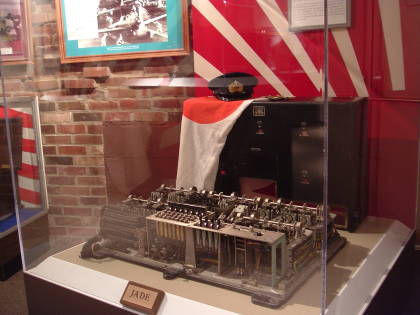

Buddhism Arrives

Buddhism was officially introduced into Japan from Korea in 552 CE. Buddhism had spread from India into Central Asia, and then moved along the Silk Road after that travel network was established in the 2nd century BCE. The monk Zhang Quian traveled along the Silk Road between 138 and 126 BCE, and Buddhism was officially introduced into China in 65 CE. Buddhism next spread to Korea.

Buddhist monks from China visited Japan during the Kofun period of 250 to 538 CE, but those visits left few traces. The Chinese Book of Liang recorded in 635 that five Buddhist monks from Gandhāra had visited Japan in 467. In 552 CE, King Seong Myong of Baekje in Korea sent a mission to the Japanese Emperor Kinmei. The group included Buddhist monks and nuns along with an image of the Buddha and a number of sutras introducing and explaining Buddhism.

In 607 the Emperor of Japan sent an envoy to China to obtain more sutras. By 627 there were 46 Buddhist temples in Japan, staffed by 816 priests and 569 nuns.

Buddhism wasn't a practical movement. It wasn't for the masses. For its first few centuries in Japan, Buddhism was staffed by educated priests who prayed for the prosperity of the nation and the Imperial house. Uneducated and unordained "people's priests" ministered to the common people, practicing a combination of Daoist and Buddhist philosophy plus some local elements of shamanism.

Buddhism and Shintō became blended. Shintō shrines were built on the grounds of Buddhist temples, and vice-versa. Both were caught up in the power struggles of weak Emperors.

The Imperial capital moved from Nara to Kyōto in 794. Buddhist monasteries grew more powerful, to the point that some established armies of warrior-monks known as Sōhei. Buddhism and Shintō were both powerful.

A period of crises arose in the late 1100s. The Imperial house lost power as the samurai gained power. In 1185 the Kamakura Shōgunate was established. The Emperor stayed in Kyōto while power moved to Kamakura with the military leadership.

Formalized Shintō, associated with the Emperor, lost influence while Buddhism, more associated with the Shōguns, gained influence. Pure Land Buddhism and Zen Buddhism were introduced. They were quickly adopted by the upper classes, and then by the common people throughout Japan. Zen in particular appealed to the samurai and also had large effects on traditional arts. Pure Land is still the largest Buddhist sect in Japan, and Zen remains very popular.

Buddhism gained a great deal of political and military power. The Shōguns imposed strict control over Buddhism, lest it become so powerful that it took over. Meanwhile, Japan cut itself off from the world. By 1641 the only foreign contact allowed was a small colony of Dutch traders at Nagasaki, on the island of Kyūshū at the far southern end of the country.

The "Black Ships" and the Suppression of Buddhism

U.S. Navy commander Matthew Perry led the "Black Ships" fleet to Japan in 1853, demanding that Japan open its ports to foreign ships. A series of treaties beginning in 1858 opened Japanese ports first to U.S. ships and then to ships from other nations. Confidence in the Shōgunate dropped, made worse by worry over China's experience against Britain in the Opium Wars. In November 1867 the last Shōgunate was terminated and power returned to the Emperor in January 1868. That was called the Meiji Restoration. In 1869 the Emperor moved his court to the Shōgun's city of Edo, now known as Tōkyō.

With the return of the Emperor, Buddhism with its foreign origin was suppressed in favor of the native Shintō. The treaties with the western nations had insisted that Japan must have freedom of religion. First, the Japanese language needed a word for "religion" in the sense used by the other countries.

Japan said that Shintō wasn't really a religion, not in the sense that the treaties used that word. The Emperor's representatives effectively said, "People in Japan can believe whatever they want, so long as they accept the divine nature of the Emperor and take part in Shintō rites honoring the deified Emperors. But since Shintō is a Japanese national tradition and not a 'religion', we have full freedom of religion."

Shinbutsu bunri is the Japanese term for the separation of Shintō from Buddhism. Shintō kamis were no longer considered to be manifestations of Buddha figures. Buddhist temples were closed, monks were forced to return to lay life or become Shintō priests, and many books, statues, bells, and other Buddhist artifacts were destroyed. Shintō became a nationalist movement.

State Shintō

"State Shintō" was a term applied by the U.S. during World War II and continuing through Occupation. It was used to describe the ideological use of Shintō on a national scale after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, and especially after 1900. It never was a Japanese term. Again, see the ambiguity of the word "religion".

The official stance was that Shintō, as defined by the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki documents in the early 700s CE, had established that the Emperor was a descendant of the gods. The divine descent was a fact, not a matter of faith, and was taught as such in schools. Worship of the Emperor, which had never been a part of Shintō, was added to traditional Shintō practices after the Meiji Restoration.

Shrines were redefined as patriotic institutions, not religious sites, and later they were given local political functions. The government took control of training Shintō priests. Traditional activities that non-Japanese people would call "religious", like sermons at shrines, and Shintō funeral services, were prohibited. An estimated 200,000 shrines before 1900 had been reduced to 120,000 by 1914, by closing shrines that did not follow the national directives.

Surprisingly, the Roman Catholic Church went along with the state's explanation. An official publication in 1936 by the Propaganda Fide, the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, agreed with the state's definition. It said that visits to shrines had "only a purely civil value".

The Emperor was still subject to the recommendations of a council controlled by the military. The military controlled the council, the council advised the Emperor, and the Emperor was divine. Military factions now had a strong influence over national rule.

There were three Emperors during the years of Imperial Japan from 1868 to 1945. Emperor Meiji ruled 1867-1912, then Emperor Taishō 1912-1926, and then Emperor Shōwa 1926-1989. Japanese emperors are referred to by posthumous names after their death. The one we call Shōwa today was known until his death by his personal name Hirohito. But in Japan he was simply "The Emperor" throughout his reign.

Emperor Taishō (birth name: Yoshihito) had neurological problems. He succeeded to the throne in 1912 but was kept out of public view as much as possible. By 1919 he no longer carried out any official duties. Hirohito was named Prince Regent in 1921, and took over some of the official duties. In December 1926, Taishō died and Hirohito became Emperor.

The military's increasing influence over the government through the 1920s and 1930s led first to Japan's occupation of multiple Chinese territories, then the Second Sino-Japanese War which started in July 1937, and then expanded into World War II.

Emperor Hirohito was required to denounce godhood after the war. On New Year's Day in 1946 the Emperor issued a statement, sometimes called the Humanity Declaration, saying that he was not an Akitsumikami, a deity in human form, and he was not descended from the sun goddess Amaterasu and her brother the storm god Susano-o. It also said that the stories of the creation of Japan as described in the early 8th century Kojiki and Nihon Shoki were myth, not history.

Or at least that was the Western interpretation... The official English translation included this passage near its end:

The ties between Us and Our People have always stood upon mutual trust and affection. They do not depend upon mere legends and myth. They are not predicated on the false conception that the Emperor is divine, and that the Japanese people are superior to other races and fated to rule the world.

General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, used the official English translation to promote the idea that the Emperor had admitted that he was not a living god.

However, the statement was phrased in a very stilted way, using the archaic formal language of the Japanese Imperial court. The Japanese people themselves struggled to understand it. Debate continues over the precise meaning of some unusual phrases, but it's clear that Emperor Hirohito did not really renounce the idea that the Emperor should be considered as a descendant of the gods.

In December 1945, the month before the Humanity Declaration, Hirohito said, "It is permissible to say that the idea that the Japanese people are descendants of the gods is a false conception; but it is absolutely impermissible to call chimerical the idea that the Emperor is a descendant of the gods." He, along with other critics of the U.S. interpretation, argued that the point was not to deny divinity. The Emperor started with a recitation of the Five Charter Oath of 1868, and the full statement was intended to make the point that Japan had already been democratic since the Meiji Restoration, and therefore the U.S. occupiers had not been the ones to bring democracy. The Imperial statement was published along with a commentary by Prime Minister Kijūrō Shidehara. That commentary addressed only the prior existence of democracy after the Meiji Restoration, and made no mention of any renunciation of divinity.

MacArthur and the U.S. State Department maintained the authority of the Emperor as the leader of the nation, in order to retain the support of the people during the years of occupation and reconstruction. But now he was just a hereditary Emperor, and not divine.

VisitingYasukuni

Shrine

The U.S.-led Occupation Authorities, known as the GHQ, planned to demolish Yasukuni Jinja, a shrine in Tōkyō which enshrined Japanese war dead from conflicts after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. The GHQ planned to build a dog-racing track there. However, the Roman Curia persuaded GHQ to leave Yasukuni Jinja standing. In 1951 the Roman Curia reaffirmed its 1936 decision that Shintō rites were not religious. Nationalists enshrined several war criminals at Yasukuni, based on secret decisions made in 1969.

After World War II, Buddhism began a resurgence. There was a demand during and after the war for Buddhist priests to conduct funerals. With Shintō still being seen as a non-religious cultural practice that encourages national unity, the people wanted some traditional religious practice and Buddhism has filled that role.

Of course, America has The Apotheosis of Washington. This is a fresco in the dome of the United States Capitol Building that depicts George Washington ascending and becoming a god. He is surrounded by various Roman deities and mid-1800s technology — the goddess Minerva with an electrical generator and batteries, the goddess Venus helping to lay the transatlantic telegraph cable with an ironclad warship in the background, the god Vulcan with a cannon and steam engine, the goddess Ceres sitting on a McCormick mechanical reaper, and so on. I wouldn't want to explain the theological meaning of that to a foreign visitor.

Over a third of Japanese people now identify themselves as "Buddhist", and that number continues to grow, while almost no one calls themself a Shintōist. Over 90% of Japanese funerals are Buddhist.

Other topics in Japan: