Across the Aegean and Back

By ferry From Mykonos to Patmos

Με

πλοίο

από

τη

Μύκονο

στην

Πάτμο

I was traveling through the islands and had been in the

Cyclades.

Now I wanted to go to Patmos,

where Saint John the Theologian saw his visions.

Patmos is in the Dodecanese group.

It's close, but not directly connected to the Cyclades by ferry.

At least not during the shoulder season,

the best time to visit Greece.

This was in the last week of September.

And so, to travel from Mykonos to Patmos,

I would have to go via Piraeus, the ferry port of Athens.

It would be a five-hour ferry from Mykonos to Piraeus,

then a little over a seven-hour ferry from there to Patmos.

If there were a direct ferry between Patmos and Mykonos or

Naxos or Paros, it would only take about two hours.

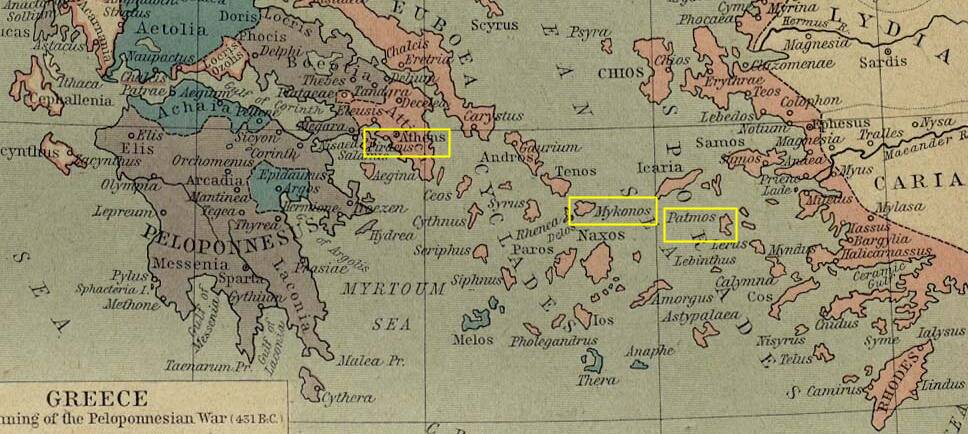

Portion of a map of Greece at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE, from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. See, west to east, Piraeus, Mykonos, and Patmos.

Leaving Mykonos

I had to get an early start because the Blue Star ferry was scheduled to leave Mykonos at 0755. I was staying in the center of Χώρα or Hora, which just means "Town" and typically designates the main settlement on an island. The main ferry terminal in Mykonos is about two kilometers north of Hora.

So, I walked along the narrow path that is the main street through Hora to the square by the waterfront. From there, along the waterfront to the taxi stand. Then I took a taxi to the new port that can handle more than one enormous cruise ship at a time. We would make two stops along the way and arrive in Piraeus at 1255. Here is my ferry coming in for a brief stop.

Then I would transfer to another Blue Star Line ferry at Piraeus, leaving there at 1500 and arriving in Patmos at 2215. The ramp is coming down, it's time to get on board because port calls are short!

Here we go! That's the old town of Mykonos in the distance beyond the moored cruise ship.

In just over a half an hour we were coming in to Tinos for a brief port call.

Then in about another 45 minutes we came into the port of Ermoupoli on Syros. Syros was settled around 3,000 BCE in the Early Bronze Age by the Cycladic civilization. The port of Ermoupoli was founded and built up during the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s. The Neorion shipyards had been the first modern shipyards in Greece. They reopened in the 1980s.

Check ferry schedules and buy tickets:

To Piraeus and Back Again

From Syros it was two and a half hours to Piraeus. The enormous shipyards of Piraeus were visible well before we got there.

The large basin of Piraeus port can hold several large ferries. We would pull in to Port Gate E8, off to the right and ahead here. From there it was two kilometers all the way around the basin to Port Gate E1 and my outbound ferry, the blue-white-and-yellow one at left here. A shuttle bus connects the various gates, saving some long treks between ferries.

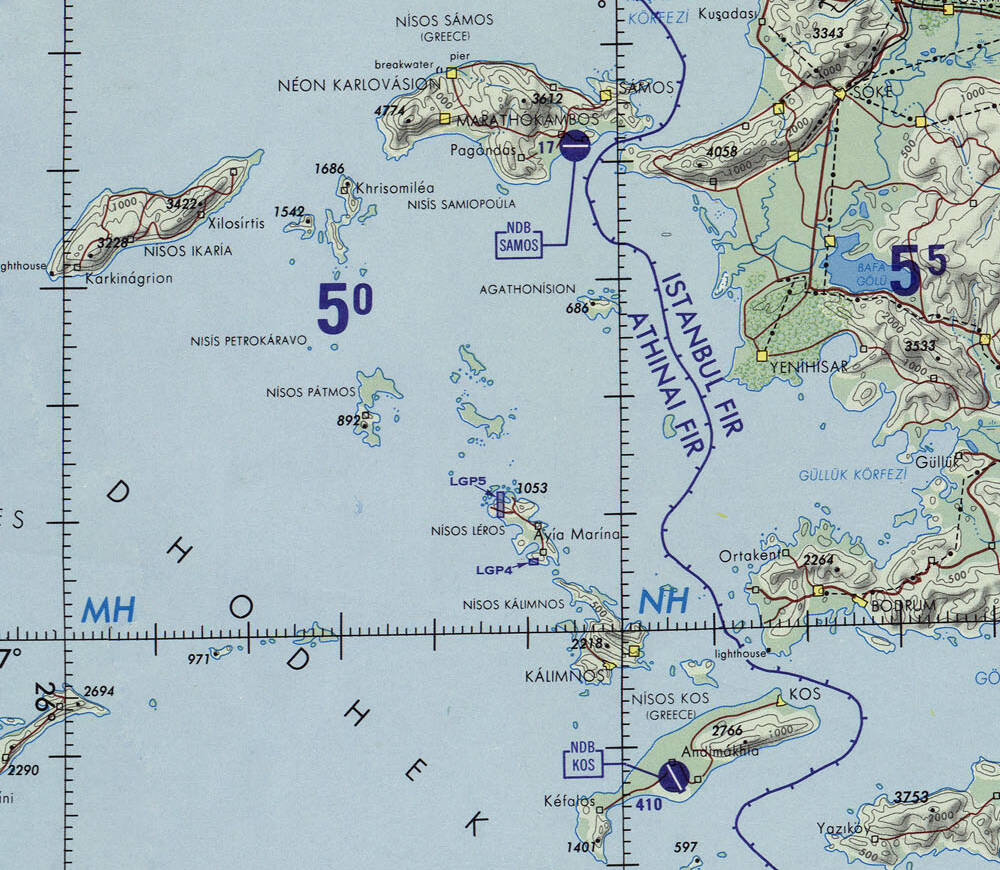

Here's a closer view of where I was headed. Patmos is close to the Turkish coast. See "NÍSOS PÁTMOS" on the map, νίσος or nisos means "island".

Portion of Operational Navigational Chart G-3 from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. As you can see here, in 1973 when the U.S. Department of Defense published this map, "Nisís" and "Nísos" were how DoD represented the Greek words for "island" in varying gender and number, and elevations were done in feet as in the 892-foot peak of Patmos.

Artemis

Greek myths say that the island was originally at the bottom of the sea. The hunting goddess Άρτεμις or Artemis, associated with western Anatolia and the Mother Goddess of West Asia, frequently visited Caria on the nearby mainland. The Carians had erected a shrine to her at Mount Latmos.

Trek AroundMount Latmos

The Moon goddess Selene cast her light on the sea, allowing Artemis to see the sunken island. She got help from her brother Apollo to convince Zeus to raise the island from the sea floor. The sun dried the land, and life sprang up.

The inhabitants from surrounding areas, including around Mount Latmos, settled on the island. They named it "Letoïs" after Artemis, the daughter of Leto.

The ancient writers didn't say much about these islands. The people living there identified themselves as Dorian Greeks who were descended from families of Argos, Sparta, and Epidaurus in southern mainland Greece.

During the Hellenistic period, in the 3rd century BCE, the inhabitants of Patmos built an ακρόπολις or akropolis, literally a "high city", at the peak of the island.

Then in the first century CE, John the Theologian was exiled to Patmos during the rule of Roman emperor Domitian.

John wrote what is now called the Book of Revelation or the Apocalypse of John, the last book of the Christian Bible. Its first word is αποκάλυψις or apokalypsis, meaning "unveiling" or "revelation".

So yes, an apocalypse is an unveiling or revelation. It is not the near-universal destruction dreamed of in catastrophic millennialism. And it certainly is not an elaborate revenge fantasy, despite American "Rapture theorist" wishes to make it so.

The Romans imposed banishment for offenses of magic, astrology, and prophecy.1 John's prophecy with political aspects would be perceived as an obvious threat to Roman political power and order. Patmos was one of three islands in this part of the Aegean the Romans used for banishment. Exile to other islands continued under subsequent rulers, all the way through the right-wing military dictatorship of 1967–1974.

The Byzantine Empire took control of Patmos in the 11th century, and the large monastery I'll visit was founded in 1088.

The Ottomans controlled Patmos for centuries, but granted privileges including tax-free trade by the monastery. Italy took control of Patmos and the rest of the Dodecanese in 1912, at the end of the Italo-Turkish war. Italy surrendered to the Allies in 1943 and Germany took over. Patmos became autonomous at the end of World War II, then joined Greece in 1948.

Approaching Patmos

The sun set behind us as we continued east across the Aegean to Patmos. When I visited on this trip in late September, one ferry ran from Piraeus to Patmos each weekday, Monday through Friday. On Tuesdays and Thursdays it ran 1500-2215. On the other days the schedule was much less convenient, 1900-0315. In high season a ferry also ran between Mykonos and Patmos three days a week.

in San Francisco

It's a long day on ferries. Bring along a bottle of wine and a copy of Revelation to read in preparation for visiting Patmos. Maybe a readable modern translation, or maybe the classic King James Version. Hunter S. Thompson wrote multiple times of getting writer's block while on the road, pulling the Gideon Bible in its King James translation out of the hotel nightstand, and reading some of Revelation to find inspiration.

It's a long pair of rides. You'd better bring both versions and plenty of wine. You can re-stock in Piraeus.

My Tuesday trip arrived in Patmos on time at 2215 and my innkeeper met me on the ferry dock. He escorted me to the guesthouse and checked me in. I dropped my things in my room and returned to the waterfront, where I could get a rather late light dinner at the Mermaids taverna across the street from the dock.

Dolmades with a cream sauce, out of the can and heated up in the microwave. No matter. It's my dinner, I have a half-litre of rough red wine in a red aluminium pitcher, and I'm on Patmos sitting across a narrow lane from my ferry arrival port.

And, of course, they add on a sweet at the end. This was like the candied apples in an apple pie.

Settling In

Guesthouses at Booking.comI had a room at Villa Zacharo, just a few blocks from the ferry dock.

It's only about 200 meters south of the port, inland along the main street.

I had my own bathroom — toilet, shower, and sink.

There was a small refrigerator and a spacious cabinet. You could move in here for an extended stay. Or at least I certainly could.

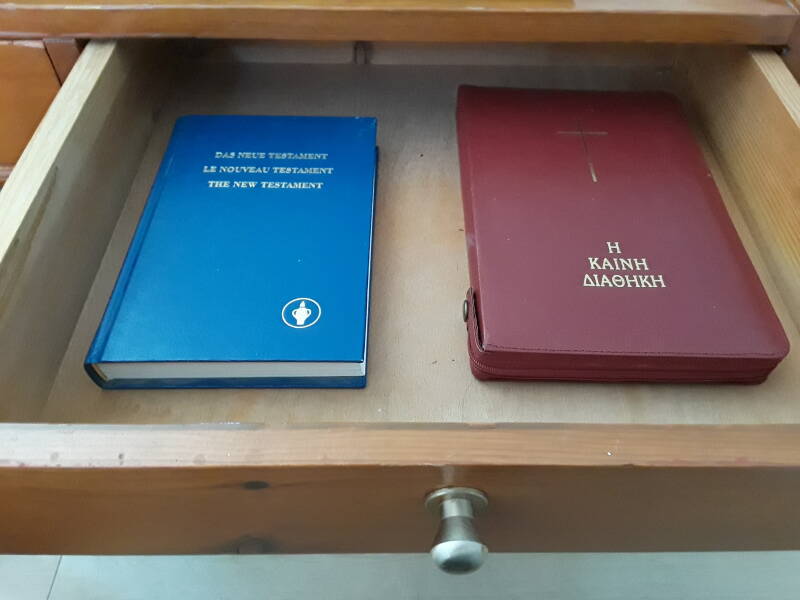

The desk held four New Testaments. Three were in a blue Gideons volume with the same text in German, French, and English. The English section was in the copyright-free and Hunter-S-Thompson-approved King James Version.

The other volume was in everyday modern Greek. Η Καινή Διαθήκη is simply "The New Testament".

Speaking of ships and languages and apocalyptic literature, the Ever Given is one of the largest container ships in the world. It's a 400-metre-long ship that can carry up to 20,000 standard twenty-foot containers. It was buffeted by winds, turned sharply to the side, and got stuck in the Suez Canal for six days starting 23 March 2021, six months before my visit to Patmos.

How to delete your Facebook accountWhen I reached Patmos, American evangelicals were still filling social media with nonsense about the English word for "Suez", spelled backwards, being the English word for "Zeus", the ancient Greek deity. Therefore, they claim, this container ship getting stuck in the canal for six days is obviously a prophecy of the end of the world in a detailed, violent, and gruesome way.

That is dumber than numerology. Let's break down just how dumb that is. To start with, Arabic is written in the Arabic script, and Greek is written in its own alphabet. "Spelled backwards" makes no sense because they're entirely different scripts, neither of which is what English is written in.

The name of the canal is السويس in the original. Transliterating Arabic is always an approximate and inconsistent process, but al-Suways is a common "English spelling". French speakers tend toward as-Suwēs, and Germans use as-Suwais. As for the Greeks, they spell it Σουέζ and seem more concerned with approximating the sound used by other European languages. Probably because they live toward the east end of the Mediterranean, where you can't help but be aware that other people speak other languages written in their own scripts.

The name of the Greek deity is Ζεύς in the nominative case, if you're talking about him, or Ζεῦ in the vocative case, if you're talking to him. That's his name in today's Greek.

Or, alternatively, Δίας or Dias. That name came from the Proto-Indo-European Dyēus meaning "Sky Father". (Or *Dyēus with the asterix used by linguists to indicate a reconstructed word) Dyēus goes back to the Neolithic, so that's truly Old-Time Religion. But Δίας is still used in today's Greek.

Proto-Indo-Europeanmythology

Proto-Indo-European is thought to have been a single language from 4500–2500 BCE, during the Late Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Most everyone in today's Europe and western and south-central Asia said Dyēus, and a majority may have worshipped him, or at least acknowledged him.

Then Proto-Indo-European began diversifying into the languages spoken today from South Asia to the British Isles, from Hindi to Scots Gaelic, including all the major languages of Europe except Finnish, Estonian, Hungarian, and Basque.

Proto-Greek speakers entered Greece at some time during the European Bronze Age, with estimates ranging from 3200 to around 2000 BCE. Mycenaean Greek is the most ancient form that we directly know about, it was written in the Linear B script.

Zeus or Dias was named Di-we and Di-wo in Mycenaean Greek in the 14th century BCE, written in Linear B as 𐀇𐀸 and 𐀇𐀺, respectively. His name shifted through various forms as Mycenaean Greek evolved through Homeric and Ancient Greek, then the Koine form used to write the New Testament, then Byzantine, then the failed ridiculous experiment that was Katherevousa, and finally today's Demotic or common, everyday Greek spoken by the Greek people.

2 Alexander turned out to be a major figure in the spread of Christianity. His military adventures in 333–323 BCE established a non-academic infantryman form of Greek as the common language all around the eastern Mediterranean and through Mesopotamia and Persia as far as the Hindu Kush and parts of the Indian subcontinent. Ideas could now be transmitted widely by voice and in writing.

Koine Greek developed from the spread of Greek culture and language following the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE.2 It became the common language across much of the Mediterranean and west Asia through the following centuries. It was used for post-classical Greek literature and scholarly work. It also was the language in which the Christian New Testament was written, and the language into which the 3rd-century BCE Septuagint translated the Hebrew Bible. Those documents could then spread easily without translation.

Koine Greek was initially pronounced like Ancient Greek, with its tonal or pitch accent and the distinction between rough and smooth breathing. The tonal or pitch accent seems to go back to Proto-Indo-European. There are parallels to the Vedic hymns, examples of the earliest form of Sanskrit. By some time between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE, tonal accent was entirely replaced by a stress accent. The loss of rough breathing changed Homer to Omeros and Hades to Aides.

By the end of Koine Greek, it was pronounced much like today's common Greek. But in its written form it retained the unneeded tonal accents and marks for rough and smooth breathing.

We're still stuck with Ancient Greek conventions in today's transcriptions of Greek. For example, in Άγια or "Holy" before the name of a saint, or the church of Holy Wisdom or "Haghia Sofia" in today's Istanbul. The Turks write it the way the Greeks have pronounced it for almost two millennia: Aya Sofya.

Back to the Ever Given —

But shipping work is still required,

I only need a little snooze,

I turn to side and block the Sooz.

Or, Continue Through Greece:

1 I, for one, would welcome the banishment of astrologers, homeopaths, and fortune tellers, all of whom are scam artists who prey on the gullible and weak.