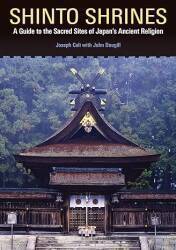

The Outer Shrine or Gekū

The Outer Shrine Complex

Previous: Meoto Iwa, the Wedded Rocks Shintō andBuddhism

The Grand Shrine of Ise

is the most holy and important shrine of Shintō.

It consists of 125 individual shrines in two major complexes.

The Outer Shrine or

Gekū,

officially known as Toyouke Daijingū,

is just a short walk from the train stations.

The Outer Shrine and the even more holy and important

Inner Shrine along with their complexes are collectively

called the Grand Shrine.

Or, officially, simply Jingū,

which is like calling it "Shrine".

Because, you see, this is

the shrine.

The Outer Shrine is dedicated to

Toyouke-Ōmikami,

the goddess of agriculture and industry.

She is enshrined or housed there so she can offer food

to the higher deity, Amaterasu Ōmikami,

who lives at the Inner Shrine.

The kami are the deities and spirits of

Shintō.

The prefix Ō-mi- is a double honorific.

So, Amaterasu is a stand-out deity among the deities.

Establishing the Grand Shrine

Shintō says that the first deities, Kuninotokotachi and Amenominakanushi, came into being on their own. They created Izanagi and Izanami, brother and sister and also husband and wife. Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun, emerged out of Izanagi's left eye. Jimmu, who became the first Emperor around 600 BCE by today's calendar, was Amaterasu's great-great-great-grandson.

Entering the Outer Shine complex.

Yamatohime-no-mikoto, the daughter of the Emperor Suinin (#11 according to the official lists), was herself divine because her father was descended from the gods. In 4 BCE this divine princess had been wandering around the area southeast of Nara for 20 years. She was looking for a place to enshrine the Sun Goddess Amaterasu. She founded the Grand Shrine near today's Ise.

Continuing further into the Gekū shrine complex.

The two documents of early Japanese history were the Kojiki (or Records of Ancient Matters), written down in 711-712 CE, and the Nihon Shoki (or Chronicles of Japan), written down about 720 CE. They were largely collections of legends and creation myths. The second one is our only document about Tenmu's life. Since it was written soon after his death, historians believe that he really existed. But since it was written during the reigns of his widow and children, no one assumes that it's totally honest.

The first building at the Inner Shrine complex was built by Emperor Tenmu, who reigned 678–686. He was the 40th Emperor, the first to be called called Tennō or "Emperor" while alive. Unlike most of the earlier Emperors, historians believe that Tenmu actually existed.

Modern historians say that the early Emperors on the official list are entirely legendary. Emperor Ankō, traditionally listed as #20, is the earliest leader generally agreed to be a historical ruler of all or at least a part of Japan. Emperor Kinmei, traditionally listed as #29 and ruling from 539 through 571, is the first Emperor for whom today's historians can verify dates.

Calligraphers create wooden plaques for visitors to the Outer Shrine at Ise.

A Hierarchy of Shrines

The Inner Shrine and Outer Shrine complexes each have their primary shrine. Those are Naikū and Gekū, respectively. But then each complex contains many more associated shrines, in categories with specific names.

Betsugū literally means "detached shrine" or "separate shrine". One of these is an auxiliary shrine for the central or main shrine, the honsha or hongū.

The next step down are the sessha, smaller auxiliary shrines.

Then the massha branch shrines, smaller yet.

Both the sessha and massha have some close connection to the kami enshrined in the main facility. They're typically a little under 2×2 meters. A smaller one might be contained within its main shrine's premises.

Shokansha are even further down the hierarchy of importance, although they might be relatively large.

These designs and organization come out of deep tradition dating back to a time long before written history. There are 32 of these additional shrines at the Outer Shrine, Gekū, and 91 at the Inner Shrine, Naikū.

The Shrines are Ancient but New

The Grand Shrine came under Imperial patronage during the Heian period of 794–1185, the peak of the Imperial court. Today it is still supported under Japanese national patronage.

KofunMegalithic

Tombs

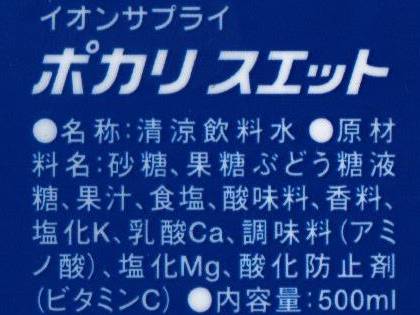

The shrines, especially the main shrine at each complex, are of an ancient architectural style called shinmei-zukuri. The extremely simple design dates back to the Kofun Period of 250–538 CE, or even earlier, the Yayoi Period of about 300 BC to 300 AD. It predates the introduction of Buddhist architecture from China. There are no nails or screws. The wood components are cut to precise shapes and fitted together. Only the shrines of Ise are allowed to use this design.

Each shrine is built from Japanese cypress, with pillars set directly on the ground. A staircase leads to the raised floor and single central doorway. The roof is made from thatched reeds, supported by two pillars, with tall finials rising diagonally at the ends.

Here is the approach to the main shrine building at Gekū, the Inner Shrine. Toyouke-Ōmikami, the goddess of agriculture and industry, is believed to reside here.

The shrine is surrounded by an outer wall. You can't take photographs within that wall, so here's the approach.

The structure you see above is just within the outer wall. It's one of those auxiliary shrines. The main shrine at Gekū lies within four nested walls. Google can show us what it looks like from above:

Each shrine site is actually a pair of identical adjacent sites. The kodenchi is the empty site next to the current structure, where the previous iteration stood and where the next one will stand.

Every twenty years an identical shrine is built on the empty site. The enshrined kami is transferred across to the new structure, and the old shrine is disassembled. The material from the old structure is then sent to shrines throughout Japan and incorporated into them.

So, the shrines are ancient, of literally prehistoric design, but they're also always new. Recent and coming reconstruction years include 1973, 1993, 2013, 2033, 2053, and so on.

The recurring reconstruction represents the Shintō views on death and the renewal of nature, and the impermanence of all things.

The reconstruction of every shrine at Ise isn't cheap. Estimated costs were ¥33 billion or US$ 0.3 billion in 1993, and then ¥55 billion or US$ 0.5 billion in 2013. About 60% comes from a fund maintained by the Grand Shrine, the remaining 40% is donated by the Emperor and the people of Japan. Each reconstruction takes eight years.

The empty field, the kodenchi, is covered with smooth stones, dark stones along the borders and white stones where the next shrine and its approach will be built. Here's the kodenchi for the Gekū main shrine.

Kodenchi — where the shrine was, and where the shrine will be.

The small hut is the oi-ya. It contains a wooden pole called the shin-no-mihashira, the new sacred central pole. This pole, no more than two meters tall, is always hidden from view.

The new shrine will be built around the oi-ya. When the new shrine is completed, the oi-ya will be disassembed inside it, exposing the sacred central pole within the shrine's central sanctuary.

A new oi-ya or hut will be built around the sacred pole inside the center of the old shrine. Then the old shrine will be disassembled around it, exposing the hut but not the pole.

The poles are always there, but always invisible. The textbook Ise: Prototype of Japanese Architecture says:

The erection of a single post in the center of a sacred area strewn with stones represents the form taken by Japanese places of worship in very ancient times; the shin-no-mihashira would thus be the survival of a symbolism from a very primitive symbolism to the present day.

Here's one of the auxiliary shrines and its small oi-ya.

And, another auxiliary shrine and its oi-ya.

To the Inner Shrine

Now I'm prepared for the grand finale, Naikū or Kōtai Jingū, the Inner Shrine.

Choose your next stop around Ise:

Or, somewhere else around Japan: