Mount Haguro

Mount Haguro and its Mountaintop Shrine Complex

This visit to north-central Honshū saw me

climbing the

2,446-step stone path to the shrine at the summit,

chatting with a priest at a significant Buddhist temple,

and exploring a town that still offers training in the

ascetic Shugendō mountain faith.

I traveled there and back across the

rugged central Tōhoku mountains.

Mount Haguro is one of a cluster of three sacred mountains

in Tōhoku, the

Three Mountains of Dewa.

Assuming you don't mind meter-deep snow,

it's the only peak accessible year-round.

An Imperial assassination in 587 drove the eldest prince

out of the Imperial court.

He fled north to these mountains, which were outside the

control of the Emperor's government.

He is credited with establishing this shrine complex.

Shugendō

formed during the 7th century CE from a mixture of

beliefs and rituals from Buddhism,

which was arriving from China;

Shintō, which was evolving out of

the kami worship that had arrived from the Korean

peninsula over the preceding millennia;

and various beliefs and practices surviving from the

original late Paleolithic inhabitants of the archipelago.

Shugendō spread to the north and merged with

the practices already established on peaks in this area.

I came to Mount Haguro after visiting

Yamadera

with its famous 1,015 stone steps.

That was just a warmup for the 2,446 stone steps at

Mount Haguro.

The remainder of this page contains what very likely is far more than you care to know about the settlement of Japan, the development of Shugendō, how Japanese Buddhism and Shintō blended over the centuries, and how the restoration of the Emperor's power in the 1860s led to Shintō's rise, militant nationalism, and World War II. You might prefer to jump to the pictures:

Start❯ By train and bus to Tsuruoka and Mount Haguro

Remember

that you're heading into a deep rabbit hole

of details, and you can instead:

Jump to the pictures

I became intrigued by the mysteries of Japanese early history and prehistory, Shintō, and Shugendō, and the content of this page got completely out of hand.

I had been to Japan three times on business trips, and then wanted to return on my own. I visited Mount Haguro on my third personal, unconstrained visit.

Visiting KoyasanOn the first personal visit I went to Koyasan, a major Buddhist site.

Visiting IseOn the second, I went to Ise with the Grand Shrine, the Wedded Rocks, and other sites related to Shintō cosmology.

This third visit which included Mount Haguro led me to feel that I had figured out a little more, probably as much as I ever could. And so this page threatened to grow from a travel blog to a thesis chapter.

Shugendō, the Ascetic Mountain Faith

Japan was first settled from the north, up to 35,000 years ago. What we now think of as traditional Japanese culture arrived much later, crossing from the Korean peninsula into southernmost Japan starting around 950 BCE.

The people arriving from the north brought east Siberian animism and shamanism. Those arriving from the Korean peninsula brought worship of kami, spirits or deities associated with features of nature or with ancestors.

The kami worship encountered the east Asian animism that had arrived from the north millennia before, and evolved into what eventually came to be called Shintō. Then that mixed with elements of the esoteric Buddhism and Taoism arriving from China to form Shugendō. The way all that happened was driven by the long process of humans settling the Japanese archepeligo.

Settlement of Japan

The Last Glacial Maximum was a period about 26,000 to 20,000 years ago when the ice sheets were at their maximum extent and the sea levels at their lowest. Sakhalin Island was joined to the Asian mainland and to Hokkaidō. An isthmus connected Hokkaidō to the then-combined Honshū, Shikoku, and Kyūshū.

Japan at the Last Glacial Maximum during the Late Pleistocene about 20,000 years ago: orange = above sea level, white = unvegetated. Thin black lines show current coastlines. From a paper in PLoS Biology.

Paleolithic big-game hunters walked into Japan from the north, from eastern Siberia into what became the islands of Sakhalin, Hokkaidō, and Honshū millennia later as the seas rose. Some traces of Paleolithic culture, mainly the stone tools of hunters, have been found in Japan from around 35,000 BCE.

The Jōmon culture appeared around 14,000 BCE. The hunter-gatherer population had settled down and began some early agriculture. The earliest known pottery in the world was found in Jiangxi, China, dating back to around 18,000 BCE. Around 16,000 BCE pottery had emerged in south China, the Amur River basin of eastern Siberia, and in Japan. Then around 14,000 BCE the Jōmon culture in Japan began creating pottery.

Jōmon is a translation of "cord-marked". The Jōmon people decorated their pottery by pressing cords into the wet clay surface. The Jōmon people made a wide variety of tools and jewelry from stone, bone, shell, and antler.

Pottery is heavy and fragile, and its use indicates that the formerly nomadic hunter-gatherer Jōmon people were settling down. Their bowls grew in size over time, indicating an increasingly settled lifestyle. The patterns became more elaborate, and gained flat bottoms so they could stably stand on a flat surface.

The glaciers continued melting and the sea level rose. Around 12,000 BCE Hokkaidō separated from Sakhalin, which separated from the Asian mainland. At that point the remaining connection between Japan and the mainland was a sea passage, the strait between the Korean peninsula and Kyūshū, the southwesternmost of the four main islands of Japan. It's about 190 kilometers across the strait, with the large Tsushima Island roughly in the middle. Tsushima, about 75×12 km, was first settled by people who crossed the strait from Japan during the Jōmon period.

Starting maybe around 1,000 BCE, certainly by 700 BCE, a completely different group of people began moving into Japan, crossing the strait from the southern Korean peninsula to Kyūshū. They're called the Yayoi, named for the neighborhood of Tōkyō where archaeologists first discovered their artifacts in the late 1800s. That's when the artifacts were found. However, the earliest archaeological evidence, much earlier than that from the Tōkyō neighborhood, is from where they first arrived in northern Kyūshū.

The new people from Korea were culturally distinct. They brought three things that we see today as defining aspects of Japanese culture. First, they spoke a Japonic or proto-Japonic language, that being a predecessor of the Japanese and Ryukyuan languages. Second, they worshiped kami, spirits associated with natural features. Third, they practiced wet-rice agriculture, growing rice in flooded paddies, as originally developed by Neolithic cultures in the Yangtze river valley of southern China.

My foray intomorphometrics

These newly arriving Japonic-speaking rice-growing kami-worshiping Yayoi people were also morphologically distinct. That is, they were built differently. Comparing the skeletons of Jōmon and Yayoi people, anthropologists find that the Yayoi were 2.5–5 cm taller with faces that were more high and narrow. Jōmon faces had more pronounced facial topography — deeper set eyes with raised brow ridges and noses.

| —10,000 BCE | Paleolithic |

| 14,000–300 BCE | Jōmon |

| 300 BCE – 300 CE | Yayoi |

| 300–538 CE | Kofun |

Agriculture is better than the hunter-gatherer lifestyle for supporting a growing population. The Yayoi people multiplied rapidly during the 300 BCE – 300 CE span called the Yayoi period. By 300 CE, almost all of the skeletons on the islands south of Hokkaidō, the archipelago's northernmost and second-largest island, were of the Yayoi type with just a slight remaining influence of the Jōmon type, resembling modern-day Japanese bodies.

As for Hokkaidō, it remained Ainu territory. Through the Edo period of 1601–1868, the Ainu still controlled the northern half of Hokkaidō.

The Yayoi made mirrors, weapons, and large ceremonial bells out of bronze. By the 1st century CE they were creating and using iron weapons and agricultural tools. They wove textiles, and built permanent villages from wood and stone. Their society became more complex and stratified as wealth accumulated through land ownership and grain storage.

Imperial kofun tombs near NaraAround 300 CE the Yayoi people began building kofun, megalithic tombs covered with keyhole-shaped earth mounds, an evolution of what previous generations had built on the Asian mainland. Kofun became the name for the period from approximately 300 CE to 538 CE, when Buddhism was introduced.

The Yayoi people had been organized and ruled on a largely local scale. By the fourth century CE they had formed a tribal alliance. What is now called the Yamato Kingship came to rule over an alliance of noble families through central and western Japan, as shown below. Yamato was a location near today's city of Nara. The leader of the Yamato Kingship eventually came to be called the Son of Heaven, using the same title applied to the Chinese sovereign during that time.

Map showing the extent of the Yamato kingship in the 4th-7th century CE, from Wikipedia.

Siddhārtha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism, was born around 563 BCE or 480 BCE in the small Shakya region in what now is Nepal. Buddhism spread into central Asia and followed the Silk Road into China by 50 CE, during the Han Dynasty, and from there to Korea around 372 CE.

Some time during the sixth century CE, King Seong of Baekje in the southwestern Korean peninsula sent a mission of monks to Emperor Kinmei in Yamato. They brought sutras or Buddhist scriptures, an image of the Buddha, and ritual banners. This mission might have been in 552 CE, or maybe in 538, neither of those dates is considered to be reliable. "Middle-sixth-century-ish" is really our best guess.

The Soga clan played a major role in the introduction and spread of Buddhism in Japan, and also controlled government policy and the order of succession of the national ruler. The legends say that Prince Shōtoku (574–622) helped lead the Soga clan to victory over anti-Buddhist clans, sent envoys to China, and even became a bodhissatva.

Shōtoku was the son of Emperor Yōmei, who ruled 585–587 as the 31st Emperor according to the traditional list. He was followed by his younger half-brother who ruled 587–592 as Emperor Sushun, #32.

Emperor Sushun, Prince Hachiko, and the Establishment of the Mount Haguro Shrine

That's enough, let's jump to the picturesThere had been a dispute as to who should follow Yōmei. However, Yōmei was supported by the Soga clan and Empress Suiko, who was his half-sister and the widow of Emperor Bidatsu (#30). Soga no Umako led the Soga clan to defeat a rival clan and install Emperor Sushun on the throne.

Emperor Sushun eventually became tired of Umako's constant reminders of how powerful he was and how the Emperor owed him for his position on the throne. The legend says that one day the Emperor killed a wild boar and then said, "As I have slain this boar, so would I slay the one I despise." Soga no Umako got the message along with a mixture of anger and fear. Under an open threat from the Emperor, Umako hired Yamatonoaya no Koma to assassinate Emperor Sushun in 592.

Prince Hachiko was the eldest son of Emperor Sushun. He had been first in line for the throne, but now was first in line for an assassination. He fled north to the coast, then northwest along the coastline of Honshū. When he reached Dewa Province, today's Yamagata Prefecture and Akita Prefecture, he was in Emishi territory, beyond the control of the Emperor and, more dangerously, the Soga clan. He stayed there and dedicated the rest of his life to religious pursuits. The legends say that he founded Dewa Sanzan, the three sacred mountains of Mount Haguro, Mount Gassan, and Mount Yudono. The Hagurosan Shrine on the peak of Mount Haguro is especially associated with him.

Confucianism and Taoism had also been arriving from China, and while they weren't as influential as Buddhism they were still significant movements. Japan's kami worship, which had arrived with the Yayoi people centuries before, became blended with elements of Buddhism and Taoism to form Shugendō. That new belief, which emphasized worship on mountain peaks, and worship of the mountains themselves, became very popular around the Imperial court in Yamato.

By the time Prince Hachiko had to flee to the north, Shugendō was well established around Yamato. In Dewa he encountered the local mountain worship traditions which still had elements of the Jōmon practices. That was really old-time religion going back to the people who had walked into Japan during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Much more recently, in the last century and a half, Prince Hachiko is "traditionally venerated" as they say at a shrine on the summit of Mount Haguro. The Imperial Household Agency, the office in charge of deciding and maintaining the details of all Imperial family members going back into myth, has officially pronounced that a shrine there is Hachiko-jinja or Hachiko Shrine. With that official status, it was guarded by Imperial soldiers through the end of World War II. That would have been much more pleasant duty than defending Pacific islands or going into the jungles of New Guinea.

The Origin of History (Sort Of)

Kojiki NihongiVolume 1 Nihongi

Volume 2

The foggy boundary of prehistory is relatively close in Japan. See the above several-decades-wide approximation as to when Buddhism was introduced. As for things like an Emperor ruling 585–587, we're pretty sure he ruled for two years. It's reasonably likely that it was in the 580s, but maybe a decade or so earlier or later. Or more. Before the early 700s it's all based on collections of legends and myths. After that, it's still pretty sketchy for a few centuries.

The first purported Japanese histories we have are the Kojiki or "Records of Ancient Matters", written in 712 CE, and the more detailed Nihon Shoki or Nihongi or "Chronicles of Japan", completed in 720 CE. Their content is largely oral tradition and legends about the creation of the universe and Japan, and the ruling family's genealogy and descent from the gods. Hence the vague and contradictory dating in much of the above, not to mention the descent from the gods.

Historians question the existence of at least the first nine emperors, and the first 15 monarchs (14 Emperors plus an Empress) are listed, even by traditionalists, as "Legendary Rulers". Historians can't find any proof that the early ones existed. Emperor Kinmei, who received that mission of Buddhism monks from Korea and is officially listed as Emperor #29, is the first Emperor for whom historians can find any verifiable dates. That's because the Koreans recorded the mission.

The early 8th century CE is rather late for the origin of history and literature. In comparison, the Greek historian Herodotus lived roughly 484–425 BCE, writing his Histories about 1,150 years before the Kojiki. Herodotus did include some myths and legends of the earlier people that he described, although he generally reported them as such. And, historians and archaeologists have found evidence for much of what he recorded, even the parts that the first readers thought were wild tales.

The Maya script of Mesoamerica goes back at least to the 3rd century BCE. Finally deciphered in the mid to late 20th century, over 90% of the Maya texts can now be read with reasonable accuracy.

As for literary works, Homer was born around the 8th century BCE and is credited with composing the Iliad and Odyssey, describing events of the 12th century BCE or thereabouts.

A millennium before Homer, the "Old Babylonian version" of the Epic of Gilgamesh dates back to the 18th century BCE, and the more complete "Standard Babylonian version" dates to the 13th–10th centuries BCE, with the story describing events of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2100 BCE.

East of there in South Asia, the Hindu Vedas were orally transmitted since the 2nd millennium BCE, and were written down in the mid-2nd to mid-1st millennium BCE. The earliest parts of the Rig Veda were composed probably in the period of 1500–1000 BCE according to some scholars, 1900–1200 BCE according to others, making them among the oldest existing texts in any Indo-European language.

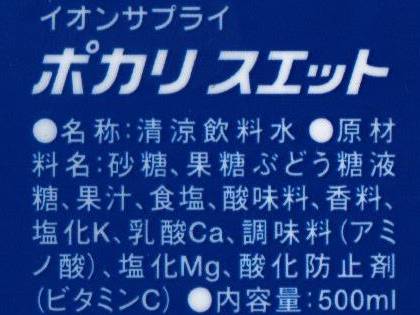

Sounding out the kana scriptsJapan didn't have written history before the early 700s CE because they didn't have writing. Chinese writing had arrived with Buddhism, and that began to be used. Japanese scholars began using some Chinese characters, calling them kanji, and later devised the phonetic katakana and hiragana scripts to spell foreign and Japanese words, respectively. The writing system was a big hit, so the Yamato rulers also adopted Chinese systems of government and the calendar.

The Murky Origins of Shintō

That's enough, let's jump to the picturesThe kami as worshiped by the early arrivals from the Korean peninsula were earth-based spirits who assisted hunter-gatherer groups. As rice cultivation grew more important, the kami came to be linked with the rice harvest. Rituals were created to entreat the kami to protect and increase the harvest. Those rituals became a symbol of the power and authority of the Emperor, the dominant ruler in Yamato. If the Emperor organized favorable rituals, then the kami would cause abundant harvests. And so, the Emperor was indirectly improving the harvest.

The Kojiki and Nihon Shoki included the new official descriptions of how the Emperor was descended from the gods. The books were written to define and solidify the Emperor's power. The first Emperor, Jimmu, was described as the grandson of the great-grandson of the sun goddess Amaterasu, and also a descendant of the storm god Susanoo. The "histories" say that he ascended to the throne in what works out to be 660 BCE. Amaterasu is said to have sent her grandson to Earth with five rice grains which had been grown in the fields of heaven. He used those five grains to transform the "wilderness" into fertile land.

Visiting the Grand Shine of IseA fifty-volume book titled the Engi-shiki was finished in 927 CE. It codified laws and customs of Japan. Its first ten volumes defines Shintō rites, including the enthronement of a new Emperor and worship at the Grand Shrine of Ise. The Engi-shiki is the earliest surviving formal codification of Shintō rites. It catalogued all the Shintō shrines and the officially-recognized and enshrined kami at the time.

By the time that Japan's indigenous religion was identified as Shintō, kami worship had moved away from its original focus on awe of natural forces. It had become a set of institutionalized rituals that were believed to ensure prosperity for the clans, and to provide religious sanction for clan chieftains and territorial rulers. As ruling power centralized, that meant divine sanction for the Emperor.

Shinbutsu bunri — Japanese Buddhism and Shintō Blend

While Shintō taught that they were descended from the deities, many of the early Emperors became interested in Buddhism. With Shintō being newly formed out of the earlier kami worship plus creation and Imperial genealogy myths, it began to also pick up imagery from Buddhism.

Shintō came to say that bodhisattvas and manifestations of the Buddha could manifest in the form of kami.

Buddhism came to say that what might seem to be localized kami might be manifestations of bodhisattvas or the Buddha.

Shintō shrines began to host Buddhist figures or small Buddhist shrines and temples. Some shrines began to represent their kami in animal or human form, instead of vaguely conceptual and amorphous nature spirits.

Buddhist temples began to host small Shintō shrines. Visitor could do a little of both observances, just in case.

What About the Ainu?

The Ainu were animists. They believed that everything in nature had a spirit or god inside.

That's enough, let's jump to the picturesThe Ainu term for that spirit is kamuy. That's very similar to the Japanese term kami, and the Ainu concept is very similar to the original Yayoi concept, before it got tangled up in legitimizing the Emperor through a connection to the gods.

One interpretation of this is that the Yayoi people crossing from the Korean peninsula brought an animistic tradition of worshiping nature gods. We have no idea what they actually called it. When they encountered the Jōmon people who had arrived millennia before from the north, both sides saw the parallels. The Yayoi then adopted the term kamuy or kami, while far to the north in Hokkaidō, the Ainu inherited the term kamuy from their predecessors. Then through the following centuries as the Yayoi became the Yamato, their practices shifted more to veneration of the ruler.

Ainu culture has been largely wiped out since Imperial Japan extended control into northern Hokkaidō. For what came before, and what little survives, see Joseph Campbell's Primitive Mythology.

The Ainu have had no professional priesthood. The village chief performs whatever religions ceremonies seem to be necessary.

Libations of sake and willow sticks are placed on an altar and prayers are recited to "send back" the spirits of killed animals, especially bears.

They had a ritual to welcome the salmon returning to the streams of their births, and a ritual to thank the salmon at the end of the season.

As for the bears, their rituals were especially elaborate and important. Every five to ten years, the Ainu would capture a bear cub during hibernation and take it to their village to raise it as if it were a human child.

When the bear reached maturity, it was time to celebrate the big ritual. Neighboring villages were invited to help celebrate. They would gather around the bear in a ritual area, shoot it with numerous ceremonial arrows, and then eat it. The remains of the bear would be "sent back" to the spirit world with the profound thanks of the people who had benefitted from it.

"The Cosmic Hunt: Variants of a Siberian — North-American Myth"Yuri Berezkin

doi:10.7592/FEJF2005.31.berezkin

Bear cults date back at least as far as Neanderthals in western Eurasia in the Middle Paleolithic. Similar rituals involving bears have been found all across Eurasia.

The constellation called Μεγάλη Άρκτος or Megali Arktos in Greek, Ursa Major in Latin, the Great Bear, is seen as a bear, usually female, by many civilizations across the Northern Hemisphere across Europe, Asia, and North America where it is visible. It is thought to possibly go back to a common myth from as far as 13,000 years into the past. That's really old-time religion.

Map of Ursa Major from the IAU and Sky & Telescope magazine.

And Others

Remnants of other east Siberian indigenous people remain. The Uilta or Уйльта people remained on Sakhalin Island. When the Empire of Japan took control of Sakhalin, the Uilta were classified as "Karafuto natives". After the Soviet Union took control of Sakhalin in 1945, some court cases in the late 1950s and 1960s recognized the Uilta as Japanese and allowed them to migrate to Hokkaidō. The Japanese government has tried to assimilate them to the point of erasing their indigenous identity.

The Nivkh or Нивхгу are another indigenous people who lived on Sakhalin long before the Russians or Japanese arrived. They share bear rituals with the Ainu.

Be Careful What You Wish For — U.S. "Gunboat Diplomacy", the Fall of the Shōgun, and the Meiji Restoration

OK, back to what we think of as the Japanese people living in Japan.

Japan underwent a sweeping sociocultural transformation through the second half of the 1800s. Japan transformed itself from an extremely isolated feudal realm into a world power, with expansionist ambitions that led to a series of wars which built up to the Second World War.

All this started with a U.S. Navy "gunboat diplomacy" episode that, frankly, had little obvious purpose or promise.

That's enough, let's jump to the picturesBe careful what you wish for.

Up through the middle of the 19th century CE, Japan was an agrarian society mostly comprised of peasants.

The peasants were ruled by daimyō, local warlords. The daimyō were in turn ruled by a shōgun, a central military dictator. The Emperor kept himself busy carrying out Shintō rituals in Kyōto, believed to be crucial to keeping Japan in the good graces of the kami.

The daimyō were served by samurai, the traditional warrior class. All through the medieval period the samurai were mostly illiterate rural landowners who operated their farms between military campaigns.

Then the Tokugawa clan came to power. During the Tokugawa Shōgunate of 1600–1868, the samurai were transformed into a bureaucracy under the roughly 180 daimyō. They were required to master administrative skills.

Then in U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew Perry commanded a fleet that sailed into the harbor of Edo, the Shōgunate capital, and the future city of Tōkyō. He sailed into Edo harbor in July 1953, when the Shōgun happened to be ill, and died a few days later, succeeded by a son who was at least as sickly. Perry returned in February 1854 with a more powerful fleet. The harbor had defensive cannons, but they were outdated. Perry's ships demonstrated that their guns had much greater range. They could remain well outside the range of the harbor's defenses and shell the city with highly explosive shells.

The goal was to force Japan to open its ports to

foreign trade.

All this was under the direction and authority of

[checks notes...]

U.S. President Millard Fillmore,

who wasn't the sharpest tool in the Presidential shed.

The Tokugawa Shōgunate of 1600 to 1868, also called the Edo Period because of its capital being based in Edo, later to become Tōkyō, was going through a rough patch. However, a nation especially created by the deities who had also created the entire universe wasn't supposed to have any rough patches, certainly none that could be taken advantage of by representatives of, well, sub-Japanese realms.

A group of samurai was extremely dissatisfied with the situation. While it took several years, by 1868 they had led a movement to overthrow the Tokugawa Shōgunate and restore the Emperor to ultimate power.

As always, the baby boy who is the first-born of his Imperial generation is given a name at birth. When he ascends to the Chrysanthemum Throne, he is simply called "The Emperor" throughout his reign. After his death, he and the years of his reign are referred to by a "reignal name". And so, from 1852 to 1989 it was:

| Birth | Ruled | Reign |

| 1852, Mutsuhito | 1867–1912 | Meiji |

| 1879, Yoshohito | 1912–1926 | Taishō |

| 1901, Hirohito | 1926–1989 | Shōwa |

Well, that's the official story. The Taishō Emperor suffered from severe neurological problems. He contracted cerebral meningitis within three weeks of birth, and very likely also suffered from neurological injuries during birth. No one questions the divine being descended from Amaterasu, the Goddess of the Sun, so we don't really know exactly what happened. But he clearly wasn't fit to rule.

After about six years of Taishō's extremely limited public exposure, Hirohito was old enough to start taking on some responsibilities. He became Regent of Japan in 1921, ruling on behalf of the now completely hidden Emperor.

Hirohito became Emperor in 1926 and ruled until his death in 1989. His reign of over 62 years was the longest of any non-mythical Emperor of Japan. It also meant that from 1867 to 1989, 122 years, Japan was effectively ruled by just two men, both of whom had been told since birth that they were directly descended from the gods.

The Meiji Restoration restored the Emperor to supreme rule over Japan. Japan had claimed Hokkaidō, Sakhalin, and the Kuril islands for centuries, but never really explored or controlled them. Late in the Tokugawa Shōgunate there was a realization that Russia was settling the area. Many Japanese settlers were sent to Hokkaidō, where many of them regarded the indigenous Ainu as sub-human but perhaps suited for forced labor. Japan finished taking control of Hokkaidō during the early years of Meiji's rule.

Shinbutsu-shūgō — Separation and Promotion of Shintō Over Buddhism

That's enough, let's jump to the picturesPart of restoring the Emperor to power over Japan was a process of "purifying" Shintō.

In the early 8th century CE the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki had created a "history" that legitimized what was a local to regional scale ruler by presenting the already-ancient kami worship as part of a creation myth in which that ruler was descended from the gods. The national cosmology said that Shintō embodied the true origins of the universe and nature of Japan.

The Meiji Restoration imposed Shinbutsu-shūgō to separate and purify Shintō from the syncretism that had built up over more than a millennium. Buddhism was seen as Chinese, foreign, although actually it came directly from Korea, while China had been a major stage along its spread from the Indian subcontinent.

This separation and purification really was another state redefinition of Shintō for political purposes. It was another statement of the uniqueness of the Emperor's descent from the creator gods.

The intent seemed to be to suppress and completely shut down Buddhism. However, people had always been having Shintō weddings with their elaborate mysterious rituals, but Buddhism provided all the funerals and burials. And, people kept dying and needing funerals.

The government realized that they couldn't completely do away with Buddhism, but it did become heavily suppressed. Or at least officially. 11 centuries of officially supported syncretism had the people pretty mixed up as to just what the vaguely religious rituals and day-to-day observances were really about.

Shugendō, however, was more heavily suppressed and largely disappeared.

As other countries began to establish relations with Japan, some questioned what seemed to be a lack of religious freedom. Everyone seemed to be required to believe that the Emperor was descended from the gods. The official explanation, eagerly accepted by other countries in order to establish trade, was that there was complete freedom of religion. Someone in Japan could believe and practice whatever they wanted, on their own time. However, of course all Japanese people believed the national cosmology explaining the creation of Japan and origin of the Emperor. In fact, they were required to accept that.

Rising Nationalism

VisitingNagasaki

The shōgunate had expelled Christian missionaries in 1635, and restricted trade with Europe and the Americas to one small Dutch trading post on a small island in Nagasaki harbor. Other than trade with Korea and China, Japan closed itself off from the world.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 opened the borders and the trade routes.

Visiting theYasukuni Shrine

The newly powerful Emperor began making up for lost time. Imperial Japan finished taking control of Hokkaido and started a series of escalating military campaigns. In 1887 the military took control of enshrining Japanese war dead at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tōkyō.

| Conflict | Years | Enshrined | |

|

Boshin War and Meiji Restoration |

Civil War | 1867-1869 | 7,751 |

| Invasion of Taiwan | Punitive expedition against the Palwan, Taiwanese aboriginal people | 1874 | 1,130 |

| Ganghwa Island Incident | Conflict with Joseon Army | 1875 | 2 |

|

Southwestern War or Seinan Sensō |

Civil War | 1877 | 6,971 |

| Imo Incident | Conflict with Joseon Rebel Army in Korea | 1882 | 14 |

| Gapsin Coup | Failed coup in late Joseon Dynasty in Korea | 1884 | 6 |

| First Sino-Japanese War | War with Qing Dynasty China over Korea | 1894-1895 | 13,619 |

| Boxer Uprising | Eight-Nation Alliance invades China | 1901 | 1,256 |

| Russo-Japanese War | War with Russian Empire over control of Korea and Manchuria | 1904-1905 | 88,429 |

| World War I and Siberian Intervention | Conflict with Central Powers over German holdings in East Asia and Pacific (1914-1918), and Allied intervention in the Russian Revolution (1918-1922) | 1914-1918 | 4,850 |

| Battle of Qingshanli | Conflict with Korean Independence Army in Manchuria | 1920 | 11 |

| Jinan Incident | Conflict with Kuomintang Chinese forces over Jinan, in Shandong, China | 1928 | 185 |

| Wushe Incident | Major uprising against Japanese colonial forces in Taiwan | 1930 | uncertain |

| Nakamura Incident | Extrajudicial killing of Japanese military personnel in Manchuria | 1931 | 19 |

| Mukden Incident | Staged event carried out by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the following Japanese invasion of Manchuria | 1931-1937 | 17,176 |

| Second Sino-Japanese War | Invasion of China leading into World War II | 1937-1941 | 191,250 |

| World War II and Indochina War | Conflict with Allied nations in Pacific Theatre of World War II, and with French and French-allied forces in Indochina | 1941-1945 | 2,133,915 |

1945

The military had continued to increase its control over Imperial rule. By the time the Allies were planning for an invasion of the Japanese Home Islands, the military and the Emperor's inner circle were anticipating 20 million Japanese deaths. The Emperor and the military leadership were willing to continue with that plan, and the Japanese people were resigned to their fate.

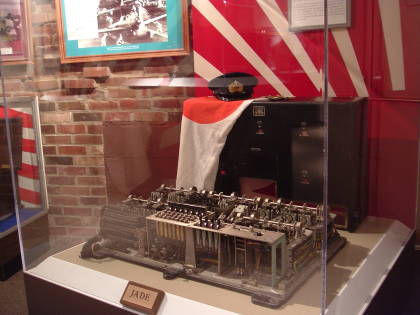

Cryptanalysis and the end of World War IISee my page on just how poorly things were going for Japan by 1945. The U.S. ended the war by dropping two nuclear bombs on Japanese cities. A one-night incendiary bombing raid on Tōkyō had killed at least as many people and destroyed a larger area than the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs combined, but the military leadership and Emperor had kept to their plan of national suicide.

After the first nuclear bomb was dropped, the Emperor attempted to intervene with his cabinet, urging them to accept the Allies' demands for surrender. Three separate coup d'état attempts immediately occurred, and senior military officials called for escalated suicide attacks on U.S. ships.

The second nuclear bomb finally led to surrender.

Cries of "We're victims of U.S. atrocities" began within a month, as the nation was terrified that the Emperor would be tried for war crimes, and possibly found guilty and executed. The government of Japan funded a public relations effort to portray the bombings as U.S. atrocities, spending heavily on the project until the financial crash of the late 1980s.

U.S. General Douglas MacArthur led the U.S. occupation of Japan. He insisted that the Emperor must not be tried for war crime or really any complicity in the series of wars. He also was personally responsible for allowing Japan's horrific "medical" experimentation programs in Manchuria to be completely overlooked, ensuring that the U.S. military got copies of the data.

MacArthur did direct that the Emperor had to deliver what has been called the "Humanity Declaration". It was written and delivered as a radio address in January 1946. The declaration was written in an archaic and intensely formal form of Japanese. The Japanese people struggled to understand it. In the official address, Hirohito really didn't deny being descended from the creator gods. But if the Japanese people were mystified by the archaic language, the Allies could make even less sense of it. They had to rely on the English translation provided by the Japanese government. It had some passages that the Allies could cite, saying that there was the required content and the promised end of what other countries called Japan's State Shintō.

Shugendō, which is what led me into this rabbit hole in the first place, was once again permitted. What has been established on Mount Haguro since 1945 is largely a major Shintō shrine on the summit, with some associated minor Buddhist temples and some as-syncretic-as-ever Shugendō activities. Are they an accurate recreation of the original practices established here around 600 CE? Undoubtedly only somewhat so, but they're the closest thing that exists.

Wow, You Made It This Far?

I warned you that it was a very deep rabbit hole!

On to the pictures and stories of my visit to Mount Haguro:

Other topics in Japan:

Yes, I kind of left the Ainu behind back when the glaciers were melting and we were going deeper and deeper into this rabbit hole.