The Bowery Through the 20th Century

A Theatre District Becomes Skid Row

The Bowery has an unusual name. Most thoroughfares in Manhattan are a Street or an Avenue. 14th Street or Third Avenue, Houston Street or Essex Avenue. Broadway is simply an English description of the colonial-era road. Why is this major north-south thoroughfare called "The Bowery"? It's Dutch. The Dutch established Nieuw-Amsterdam or New Amsterdam in 1624, and Bowery comes from an old Dutch word.

This road is the oldest thoroughfare on Manhattan Island, as it was a footpath of the Lenape natives running north to south over the length of the island. The road today is basically the southern extension of the very short Fourth Avenue merged with Third Avenue, and the name also applies to the neighborhood extending a few blocks to its east and west. In the mid 1600s this area contained several large farms and was known by the now-antiquated Dutch word Bouwerij, meaning farm, as it connected the settlement in today's Financial District to what were outlying farm districts. Bowery is the English spelling.

The British took over the territory in 1664 and renamed the settlement New York. By the early 1800s the city had grown and the area was no longer a farming area. The Bowery was the home of the wealthy and famous and became New York's theatre district through the 1800s.

As the city expanded further toward the north, the Bowery began to go downhill. By the 1860s the entertainment had changed to low-brow concert halls, German beer gardens, dime museums, gambling parlors, and brothels. Businesses were replaced by pawnshops and flophouses. The first YMCA opened on the Bowery in 1873, and the Bowery Mission was founded in 1880. Prostitution became more prominent through the 1890s.

In the Bowery in the early 1920s, at the start of Prohibition, the drink of choice was a cloudy mixture called "Smoke". Smoke was supposedly a very simple cocktail, a mixture of water and alcohol selling for $0.15 per glass. In reality it was almost pure methanol.

Ethanol or CH3-CH2-OH is called grain alcohol because it has been produced by yeast consuming starches in grain. It can then be distilled to higher concentrations.

Methanol or CH3OH is called wood alcohol because in the 1920s it was produced chiefly from wood. If you heat hydrocarbon material to high temperatures in an enviroment with little oxygen, long molecules "crack" or break down. This pyrolysis or destructive distillation was used to break coal down into coal tar and coal gas, and to break wood down into methanol, turpentine, tar, and many other industrially useful liquids.

Methanol and ethanol have similar smells. The danger is that when you drink methanol your body metabolizes it first to formaldehyde and then to formic acid. Formic acid is poisonous to the nervous system, possibly causing blindness because of its effect on the optic nerves, or possibly causing death. Blindness can result from a dose as small as 10 mL, and death from 30 mL, although 100 mL or 1-2 mL per kg body weight is a more typical fatal dose.

The "Smoke" of the early 1920s was cheap and intoxicating, but potentially lethal. There were "Smoke joints" in paint stores (where methanol was used and sold as a solvent), drug stores, and markets. In the worse periods there was about one Smoke death per day along the Bowery.

Amazon

ASIN: 014311882X

Amazon

ASIN: B0012GVMI0

The movie She Done Him Wrong, made in 1933 during the Great Depression, looked back to a light-hearted version of the 1890s, a decade of the Bowery's rapid decline. It starred Mae West as a bawdy singer in a Bowery saloon and Cary Grant as a federal agent working undercover as a mission worker.

Poster for a Bowery theatre show around the time that the Bowery began its decline, in my cabin at the Bowery House.

The indigent Bowery population varied, with booms immediately after both World Wars when men were processed out of the military in New York City and given money with which to get home. Many of them stayed on in the Bowery SROs, never leaving. Then the hard times of the Depression also caused a large surge in the Bowery population.

The G.I. Bill of 1944 provided educational opportunities leading to economic opportunities for veterans, and the Bowery population began to decline. After a peak of maybe 75,000 during the 1930s, it was down to 15,000 in 1949.

However, the Bowery was the city's Skid Row from the 1940s through the 1970s, with the most helpless derelicts remaining there.

Well-intentioned outrage about conditions lead to the unintended result of shutting down SROs and pushing some of the residents from bad conditions in SROs to even worse conditions on the streets. This is similar to what happened to public mental health care in the U.S. from the late 1960s through the 1980s.

I lay there in my open-top cubicle room looking at the ceiling. ... I listened to the grunts and squeals and snarls in the nightmare half-light of random, broken lust.

It was like the room of a Russian saint: one bed, a candle burning, stone walls that oozed moisture, and a crazy makeshift ikon of some kind that he had made.

On The Road, Jack Kerouac

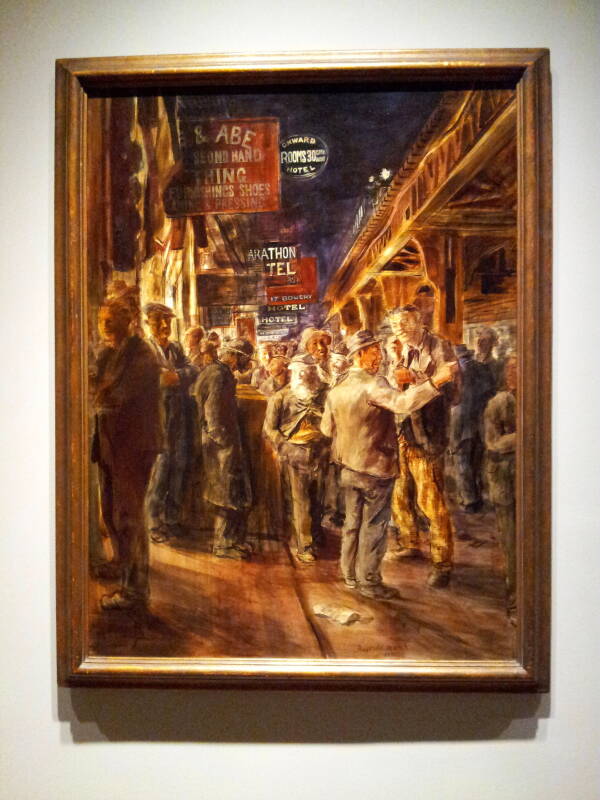

The Bowery, 1930, by Reginald Marsh

(1898-1954), in the collection of the Metropolitan

Museum of Art.

The placard reads:

Marsh's scenes of Depression-era New York

highlighted the hobos of the Bowery,

where he frequently sketched.

Using a brown palette, Marsh painted this

crowded scene of the down and out standing

along the Bowery surrounded by signage and

the Third Avenue El above.

In 1929 Benton introduced his close friend

Marsh to egg tempera, and from 1929 to 1940

it became his preferred medium for major

works such as "The Bowery".

Marsh's rhythmic and often bawdy compositions

were influenced by Renaissance and Baroque

masters but nonetheless deeply rooted in the

harsh realities of 1930s America.

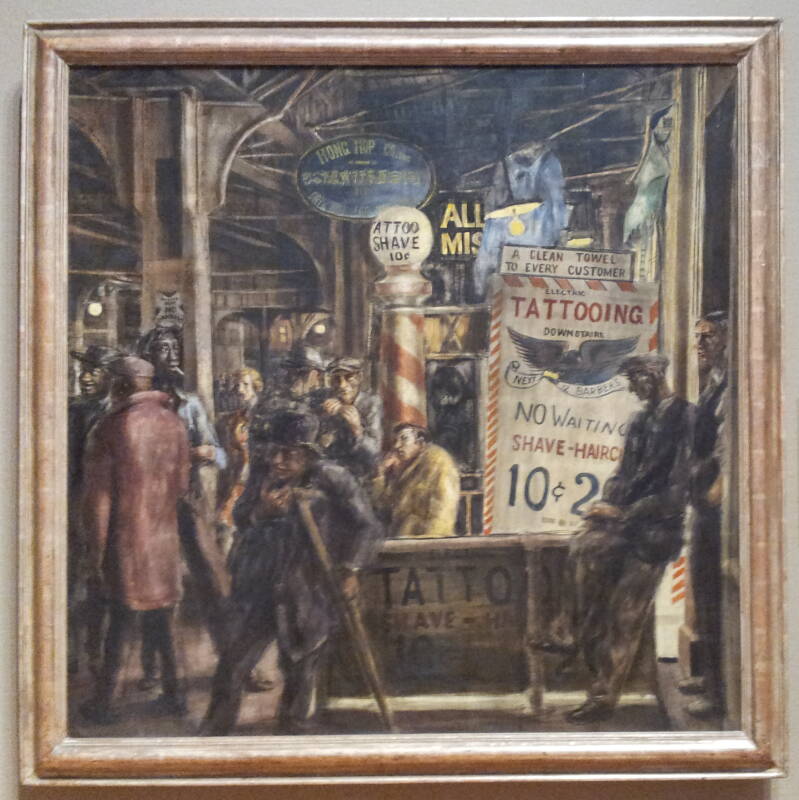

Tattoo and Haircut, 1932, by Reginald Marsh

(1898-1954), in the collection of the

Art Institute of Chicago.

The placard reads:

Of the foremost realists of the 1930s,

Reginald Marsh was fascinated by public behavior

and the exciting commotion of New York.

"Tattoo and Haircut" portrays a busy scene

of people below the massive structure of

the El on the Bowery,

then an area notorious as a skid row.

Rendered in Marsh's gently satirical style

are several city types: a derelict on crutches,

loitering men conversing or smoking cigarettes,

a chic woman walking by herself.

Marsh used an egg tempera medium to fill

every inch of the composition with details,

from architectural elements to sign and text.

Introduced to the artist by the muralist

Thomas Hart Benton, the medium suited Marsh's

keen skills as a draftsman.

Here he added successive films of tempera in

muted colors, using its mottled, uneven

surface to emphasize the grimy nature of

this world.

His technique thus reinforces his presentation

of the subject: cacophonous, dilapidated,

and dim, yet vibrantly alive.

Other Bowery SROs, Dormitories, and Flophouses

Up In The Old Hotel is a wonderful book by Joseph Mitchell. In 1929 he moved from a small farming town in the swamp country of North Carolina to New York City, where he became a reporter and feature writer. He wrote for The World, The Herald Tribune, and The World-Telegram. Then in 1938 he took a job with The New Yorker, where he stayed for the rest of his career. Up In The Old Hotel is a collection of Mitchell's pieces for The New Yorker.

The title character of the article Mazie (1940) worked in the ticket cage at the Venice theater in the Bowery. One paragraph describes a Bowery denizen who lists several of the Bowery SROs, dormitories, and flophouses:

Eddie Guest is a gloomy, defeated ex-Greenwich Village poet who has been around the Bowery off and on for eight or nine years. He mutters poetry to himself constantly and is taken to Bellevue for observation about once a year. He carries all his possessions in a greasy beach bag and sleeps in flophouses, never staying in one two nights in success, because, he says, he doesn't want his enemies to know where he is. During the day he wanders in and out of various downtown branches of the Public Library. At the Venice one night he saw "The River", the moving picture in which the names of the tributaries of the Mississippi were made into a poem. When he came out, he stopped at Mazie's cage, spread his arms, and recited the names of many of the walk-up hotels on the Bowery. "The Alabama Hotel, the Comet, and the Uncle Sam House," he said, in a declamatory voice, "the Dandy, the Defender, the Niagra, the Owl, the Victoria House and the Grand Windsor Hotel, the Houston, the Mascot, the Palace, the Progress, the Palma House and the White House Hotel, the Newport, the Crystal, the Lion and the Marathon. All flophouses. All on the Bowery. Each and all my home, sweet home."

Mazie describes the sign above the entrance of the Victoria House as reading: "ROOMS WITH ELECTRIC LIGHTS, 30¢". The article Professor Sea Gull (1942) mentions the Hotel Defender at 300 Bowery.

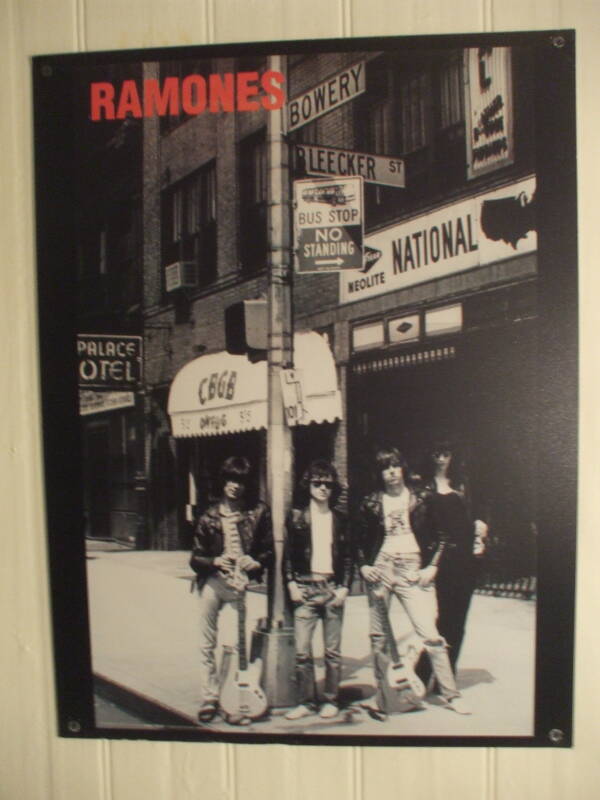

Poster of The Ramones in front of CBGB, on Bowery at Bleecker. CBGB was on the ground floor of the Palace Hotel, described by Joseph Mitchell in the 1940s.

300 Bowery, the former Hotel Defender, now with a shop selling cappucino machines on the ground floor.

The article A Sporting Man (1941) is a profile of a man named Dutch who described doing delivery work on the Bowery in the 1890s.

At that time, in 1894, the Bowery was just beginning to go to seed; it was declining as a theatrical street, but its saloons, dance halls, dime museums, gambling rooms, and brothels were still thriving. In that year, in fact, according to a police census, there were eighty-nine drinking establishments on a street, and it is only a mile long. On some of the side streets there were brothels in nearly every house; Dutch refers to them as "free-and-easies."

He goes on to describe the Occidental, the Worden House, and Honest John Howard's Kenmore Hotel as "classy Bowery hotels" in the 1890s. By 1941 the Occidental, at the southwest corner of Broome and Bowery, was still standing, and you could stay there for three dollars a week. In the mid 2010s, it was the Sohotel and once again a respectable hotel.

The former Occidental hotel on the southwest corner of Broome and Bowery is now the Sohotel.

White House Changes Hands

Mike Ghelardi took over operating the White House for an uncle in 1980. Pressure increased, including a 1996 court decision including SROs in city rent regulations, making it difficult to evict residents.

Mike, the last Ghelardi, sold the White House in 1998 to Meyer Muschel. A corporate attorney, Muschel managed to increase rents for the tenants. He also did the renovation that divided it into a permanent section for residents and a transient side run as a hostel.

Muschel sold the property in 2007 to Metro Sixteen Hotel for $7.8 million, although he stayed on as property manager. Metro Sixteen Hotel is owned by Sam Chang, who has made a fortune developing hotels for budget travelers. By 2009 Sam Chang owned hotels with a total of 4,000 rooms in New York City, including a 24-story Hilton Garden Inn and one building on 39th Street combining three chain hotels: a Hampton Inn, Candlewood Suites, and Holiday Inn Express.

The 2008 inclusion of 340 Bowery in the NoHo Historic District Extension came as a surprise, and one of Metro Sixteen's lawyers said that it would not have been purchased if there had been any idea it was about to be included in a historic district.

In 2009 most of the tenants owed at least two months' rent, and some hadn't paid since the 2007 purchase. The rents had gone up to $8.32 per night by then, adding up to about $250 per month or a little over $3,000 per year. One of the tenants, Roland Davies, has demanded improvements in the building and has filed 23 lawsuits against the owners while acting as his own attorney.

Meanwhile Chang's company had other problems. In 2009 the New York Attorney General accused a contractor with whom Chang had worked of paying non-union laborers based on skin color — $25/hour for white carpenters, $18/hour for blacks, and $15 for Latinos and Brazilians. In 2011 the company had to pay a fine for alleged price fixing.

In 2011 Chang's company proposed converting the property into a 10-story hotel, but the city denied that plan. In early 2014 a similar proposal for a 9-story hotel was also denied.

The deed was apparently transferred when the White House shut down its hostel operation in September 2014. At that point only nine permanent residents were left.

If you haven't guessed yet, I have stayed at the White House

several times, always on the transient or hostel side

of the house.

I first stayed there in 2005.

Then:

2005: 3 nights in April, 5 in May, and 4 in August;

2006: 4 nights in April and 8 in July;

2007: 5 nights in May, 11 in July— August, 3 in December;

2008: 5 nights in June;

2009: 8 nights in January—February, 4 in July;

2011: 6 nights in March, 8 in September, 3 in October—November;

2012: 8 nights in July, 5 in November;

2013: 5 nights in January and 4 in December.

99 nights overall, a total of 3 months plus a week.

It was closed from September 2009 until January 2011.

It closed down, apparently for good, in September 2014.

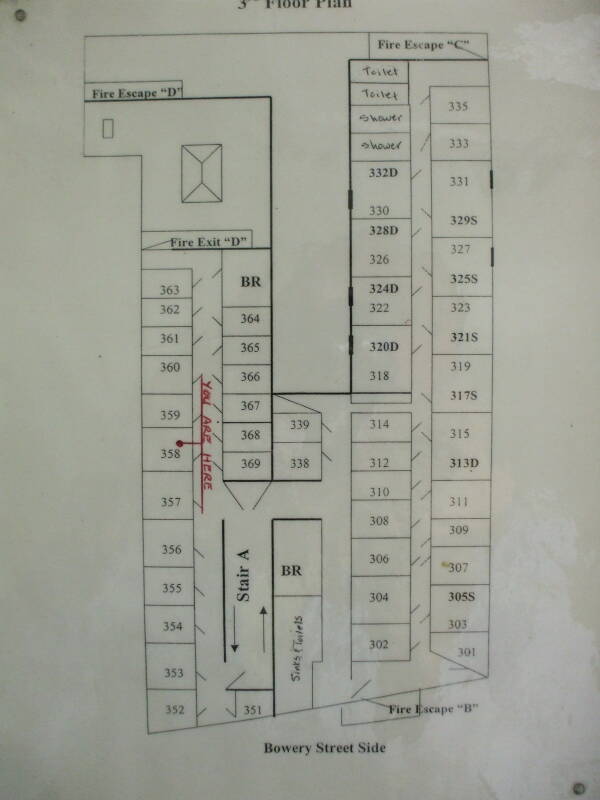

On the virtual tour on a later page, you will see that the permanent residents were on the south side, the hostel on the north side. There was one staircase up from the lobby, the permanent resident side was to the left or south, the transient or hostel side to the right or north. Keys opened the locking doors leading from either side off the staircase.

A few times, however, the residential side door was propped open and we transients could peep in. Signs on the permanent resident side listed rules starting with Rule #1: No screaming, no fighting, no spitting.

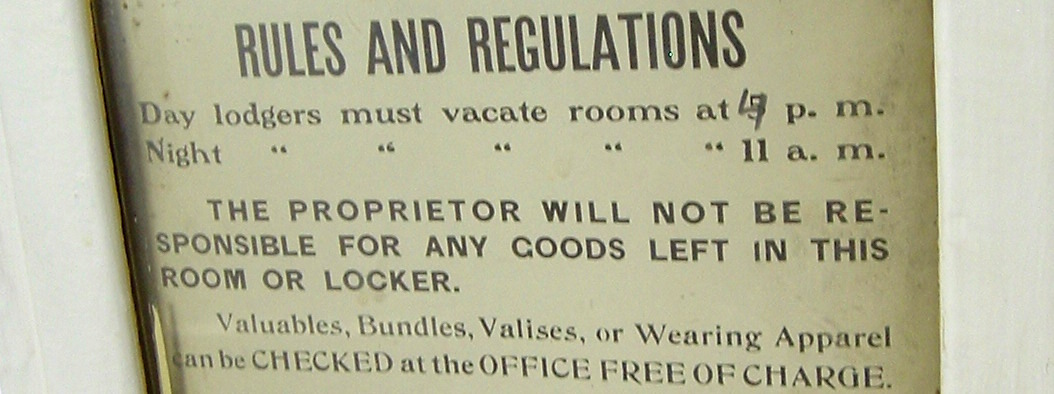

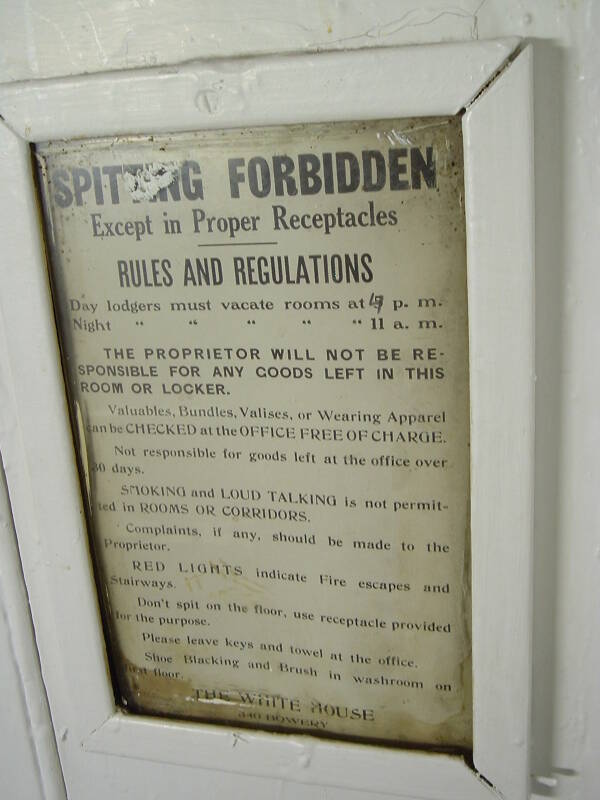

Some older signs were left in place on the transient or hostel side, including the one seen below. It dates back to when people carried "bundles and valises" and at that time there were both day lodgers and night lodgers.

The floor plan above was posted in the wrong place, it was intended for room #358 on the permanent resident side. I photographed this in my room (or cubicle or cabin) on the transient or hostel side.

Rooms 301–339 are on the transient or hostel side,

rooms 351–369 are on the permanent resident side.

One night I was in Karpaty Bar or Карпаті Бар,) also called the Sly Fox, a Ukrainian place on Second Avenue just south of 9th Street. Dave on the adjacent stool asked me where I lived. I said I wasn't from the area but I often stayed at a place called the White House.

He was startled to hear that, as he had stayed at the White House for four nights several years before "when it was all derelicts." He verified that the name signified that SRO segregation continued into the late 1980s and early 1990s. Black men weren't allowed to stay at the White House unless they were older. What were seen as "the young troublemakers" were sent across the street to the Paradise or further south along Bowery.

BucovinaDave went on to casually mention how the Karpaty wasn't strictly Ukrainian but Carpathian, hence the name, and specifically related to the Bucovina area that spans southwestern Ukraine and northeastern Romania. He was familiar with Bucovina, as I was. So, just because someone stayed at the White House back in the day doesn't mean that they aren't well traveled and informed.

A Tour of

the White House

Next: Let's tour the White House! Lots of pictures and explanations of the entry and lobby, the staircases and hallways, the individual cabins, and the bathrooms. Plus a look around the neighborhood.

USA Travel Destinations

Back to International Travel