Rethymno

From the Minoans to the Ottomans

Guesthouses at Booking.com

After visiting some of the mountain villages involved with

the Andartes and the Cretan Resistance during

World War II, I continued along the north coast to

Rethymno.

It's

Ρέθυμνο,

spelled various ways in the Latin alphabet —

Rethymno, Rethimno, Rethimnon, ...

The Venetians called it Retimo,

the Ottomans called it Resmo.

I was staying at the Route 66 guesthouse

at Eiaggelou Daskalaki 66.

It was a pleasant walk of just two and a half kilometers

to the beach area, with the marina, harbor, and old town

just beyond that.

A long strip along the beach is lined with restaurants and bars. Rethymno's economy is largely based on tourism.

Rethymno was founded by the Minoan civilization, and became prominent enough to mint its own coins. "Rethymno" is a pre-Greek name and probably comes from Minoan times. Ptolemy and Pliny the Elder both described it as the first town east of Amphimalla on the north coast of Crete. The modern city of 34,000 is built on top of the Minoan city.

The old town you see today was built by the Republic of Venice. The armies of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 had decided that it would be too much trouble to go all the way to Jerusalem. The people in Constantinople were foreign enough, practicing a religion that was different enough, in a city that was wealthy enough to make it an attractive target.

The crusader armies sacked Constantinople, killed many of its residents, and divided the Byzantine Empire into several disorganized pieces.

The Venetians controlled Crete from 1205 to 1669. They built most of the old town of Rethymno.

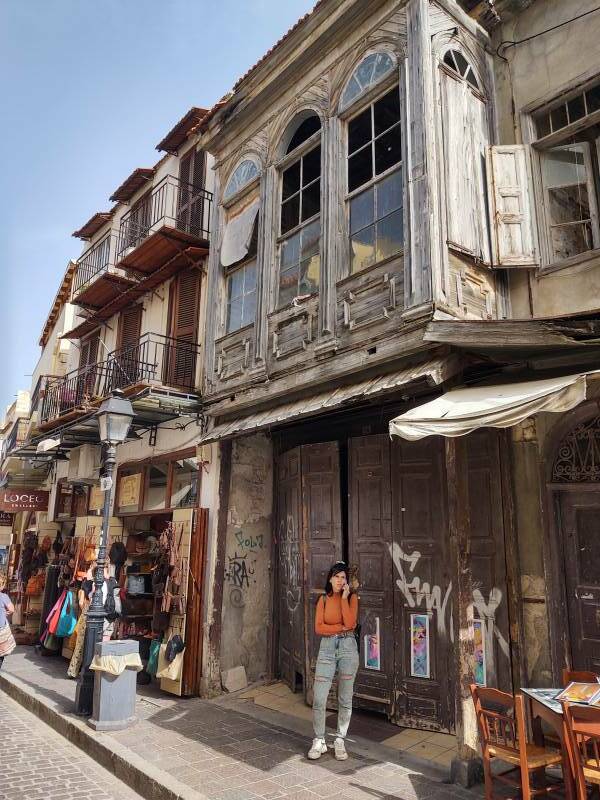

The Ottomans took over Crete during the Cretan War of 1645–1669, and ruled Crete from 1669 to 1898. They made Rethymno the center of a sanjak. They added some Ottoman architecture, like these houses with overhanging upper floors.

Much of the old town is tourist oriented today.

The Neratze Mosque was originally built in 1601 as the main church of a small Augustinian monastery. It was converted to a mosque in 1646, and the tiled roof was replaced by three small domes. It was also known as the Gazi Hussein Mosque after the Turkish governor who oversaw the conversion.

After the Turks left, it was converted to an Orthodox church.

Now it's a music school and concert hall.

The 27-meter minaret was built in 1887.

The Archaeological Museum is across the large Titos Petychakis square. A memorial on its wall facing onto the square commemorates Greek towns in Asia Minor forcibly depopulated by the population exchange of 1923.

The Venetian governor Rimondi built the Rimondi Fountain in 1621. Three Venetian lions served as water spouts.

There are plenty of cafés where you can sit and watch everyone pass by.

The Battle of Rethymno was part of the German invasion of Crete during World War II.

Italy had invaded Greece on 28 October 1940. British forces garrisoned Crete, freeing the Greek Fifth Cretan Division to reinforce the mainland campaign.

Romanian oil fields enroute from Athens to ParisThe Greeks could hold off the Italians. With their forces now on Crete, the British Royal Navy had excellent harbors, and the US and British had airfields within range of the Romanian oil fields around Ploeşti, the source of most of Germany's oil supply.

German forces overran Greece in April 1941 and the Allied troops evacuated the mainland. By this time the British had built air fields along the north coast of Crete at Maleme, Heraklion, and Rethymno.

British and Greek forces being evacuated from the mainland to Crete largely lacked any equipment beyond their personal weapons, and many didn't even have those. There were 2,300 Greek soldiers in the Rethymno area, but few of them had much training. Not all of them had rifles. Of those who did, ammunition was limited to an average of 20 rounds per man. Many had only three rounds.

The German sent a force of about 1,700, the 2nd Parachute Regiment of the 7th Air Division, minus one battalion. They started landing on 20 May 1941.

The German parachutes and their mechanism for opening them with static lines made for a severe disadvantage. The German paratroops had to dive head-first out of the plane and then land on all fours. They had to wear coveralls over the parachute harness and equipment to prevent fouling the static lines. Weapons other than a pistol or grenades had to be dropped in separate containers. The parachutes couldn't be steered.

Given the inability to steer the parachutes and the lack of weapons until they reached the weapons containers, German doctrine required that they jump from no higher than 400 feet from aircraft flying slow, straight, and level. If the plane wasn't shot down, and the Cretans didn't shoot them, the paratroopers ran a high risk of wrist injuries in their on-all-fours landings.

Despite suffering more casualties than they had during the entire Balkans campaign up to that point, the Germans captured Maleme airfield and the Chania port and began pushing the Allies east and south. The Allies concluded that Crete was lost on 26 May and began evacuation the next day.

Visiting the Normandy Landing BeachesGermany attempted no further airborne operation through the end of the war. U.S. and British commanders, however, made careful notes, developed successful airborne equipment and operating procedures, and used them on a large scale in Normandy in June 1944 and later in the Allied advance toward Berlin.

Or, Continue Through Greece:

Where next?