Itsukushima Shrine

By Tram and Ferry to the Shrine

I had arrived in Hiroshima the evening

before, and now it was time to visit

Itsukushima Shrine.

It's on an island in the bay, not far from the city.

It's one of the most photographed, and most visited,

sites in Japan.

I can take one of the city trams to the end of its line,

and then the sacred island is a short ferry ride from there.

The streetcar system started operation in 1912, with a few

pre-World-War-II cars still in service, so the trip itself

will be interesting.

Then in the evening, back into Hiroshima for visits to

a whisky bar and an izakaya.

The #2 tram line is a short walk from the J-Hoppers hostel where I'm staying. I'll take this tram to Miyajima Guchi, the end of the line.

Miya jima literally means "shrine island", and is the common name for the island. Guchi means "portal" or "entrance/exit". The end of the tram line connects to the ferry to the island with the shrine.

It's a ¥270 tram ride to the end of the line, you pay in exact change as you exit the tram. It takes almost an hour to get from the city center to the Miyajima ferry terminal.

It's a short walk between the tram station and the ferry terminal. There are two competing ferry lines, both charge the same, about ¥200 for the 10 minute crossing. Here I'm leaving on board one ferry as another arrives.

Hiroshima is visible in the distance, looking to the north past another ferry.

Here's the view the opposite way, looking south between Miyajima on the left and the "mainland" of Honshū on the right.

We're headed to Miyajima. The entire island is considered to be a shrine. It is dedicated to the three deities of seas and storms.

Japanesecosmology Shintō

According to Japanese cosmology, the very first deities were Kuninotokotachi and Amenominakanushi, who came into being on their own.

They created Izanagi and Izanami, who were brother and sister and also husband and wife. Those two gave birth to the islands of Japan and many of Shintō's deities or spirits, the kami.

Izanami died after giving birth to the fire-god Kagu-tsuchi, which sounds like a horrible plan. Izanagi killed the fire god, and then went to Yomi-no-kuni or the Underworld in hopes of rescuing his sister-wife. Like Persephone of Greek myth, she was unable to leave because she had eaten food prepared in the Underworld.

While cleaning himself after his return, Izanagi gave birth to Ameterasu, the sun goddess, from his left eye; Tsukuyomi, the moon god, from his right eye, and Susano-o no Mikoto, the storm god, from his nose. Like Athena emerging from Zeus's head, multiplied times three.

Amaterasu, also known as Amaterasu-ōmikami, is the goddess of the sun and the entire universe. And yes, the entire universe should include the sun — do not expect rigorous logic from Shintō. Her grandson's great-grandson Jimmu became the first Emperor of Japan.

Her brother Susano-o no Mikoto had three daughters: Ichikishimahime no mikoto, Tagorihime no mikoto, and Tagitsuhime no mikoto, goddesses of seas and storms like their old man.

The shrine and island are dedicated to those three storm goddesses, nieces of Amaterasu, not the first deity but the top one.

The bright vermilion shrine becomes visible as we draw closer. Mount Misen behind it is the sacred mountain. It has multiple peaks, the tallest at 535 meters.

The Shintō shrine is said to have been established in 593 by Saeki Kuramoto.

Kōya-sanThen the Buddhist monk Kūkai, who founded the Shingon sect of Buddhism and the mountaintop temple complex at Kōya-san, visited the mountain in 806. They say that he lit a fire near the peak which is still burning today.

The complex you find today is popularly attributed to Taira no Kiyomori, a daimyō or powerful warlord who contributed to the construction in 1168. He established Japan's first samurai-dominated administrative government. The Taira clan were in volved in maritime trade with the Sung dynasty of China, and were attempting to monopolize international trade routes through the Inland Sea. With the shrine dedicated to Shintō deities of sea and storms, this was a natural fit.

The Chinese Book of Liang recorded in 635 that five Buddhist monks from Gandhāra had visited Japan in 467. Buddhism wasn't initially for the masses. For its first few centuries in Japan, Buddhist temples were staffed by educated priests who prayed for the prosperity of the nation and the Imperial house.

Shintō andBuddhism

Uneducated, unordained, and unofficial "people's priests" ministered to the common people with a combination of Daoist and Buddhist philosophy mixed with elements of the native shamanism that had been the origin of Shintō.

As the samurai and daimyō evolved into a Shōgun leadership, they became more linked to Buddhism, especially the Zen sect.

Ritualized Shintō presented the Emperor as a descendant of the gods. The emperor became more of a figurehead, carrying out sacred rituals and leaving secular control to the Shōgun.

The concept of shinbutsu-shūgō held that a Shintō kami could manifest as a Buddhist bodhisattva or bosatsu in Japanese. Buddhist temples began hosting Shintō shrines, and vice-versa.

Pulling in to the ferry terminal, you see that it's a short walk to the shrine complex.

The shōgunate fell from power after Matthew Perry's U.S. Navy flotilla forced its way into the harbor at Edo, soon to be renamed Tōkyō, in 1868.

The Emperor returned to power, and Shintō with him (and this eventually led to the Cult of the Emperor and World War II). This was the Meiji Restoration. Many Buddhist influences were erased from Shintō shrine complexes, or at least scaled way back. Itsukushima was judged to be overly Buddhist, and was initially scheduled for destruction. The new government allowed it to survive as long as it was partly de-Buddha-fied.

There are, of course, cat cafés and owl cafés near the ferry terminal.

Plus many other cafés and shops.

With the entire island being a pure Shintō shrine, there are supposed to be no births or deaths. Commoners were allowed to approach only by boat, passing through the torii at high tide, and approaching the shrine but not landing. Since 1878 and continuing to today, if you're about to give birth or die, you're supposed to take the ferry to Honshū for your messy biological transitions. If you're forbidden to die here, you certainly can't be buried here. That works out, as Shintō marriages are common but funerals tend to be Buddhist.

I had timed my visit to arrive at low tide.

At high tide the water line will be up around the shrine buildings, making it appear to float on the water.

The main torii stands in front of the shrine. A torii marks a passage into more sacred space. At low tide, you can walk out to it.

Both Shintō shrines and Buddhist temples are regularly rebuilt. The great shrine at Ise, celebrating the Emperor's descent from the gods, takes this to an extreme. Its collection of 125 individual shrines is entirely rebuilt every 20 years. A replacement is built next to each shrine, and then the old ones are decommissioned and disassembled.

This torii was last rebuilt in 1875, with significant repairs from time to time since then. It is said to be the 8th torii built here since 1168. It's large. The two main columns are 10.9 meters apart, and the ridgeline is 16.6 meters above the ground.

The additional legs in front of and behind each main pillar make this the Ryōbo Shintō or Dual Shintō style, marking an association with the esoteric Shingon sect of Buddhism founded by Kūkai.

We can look back to the main shrine from near the torii. This entire area is underwater at high tide.

The main columns of the torii are made from wood from the camphor laurel tree. The wood contains camphor, a strong-smelling waxy, transparent, flammable solid. The camphor preserves the exposed and periodically submerged wood.

Camphor was extracted from wood and used in religious ceremonies in India in very ancient times.

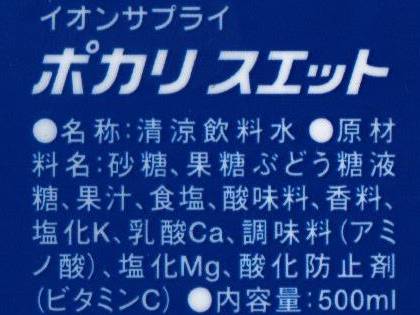

Around 1907 and 1908, Imperial Japan tried to monopolize the production of natural camphor as an Asian forest product under Japan's control. The price of camphor was climbing. It increased in price by a factor of seven to eight over the next ten years because of the global trade disruption and increased demand for explosives driven by World War I.

The 1918VapoRub craze

Plus, camphor was the primary active ingredient in Vick's VapoRub. During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, there was a mistaken belief that camphor-laden VapoRub could provide immunity against that virus-borne disease.

But then industrial synthesis methods became common. Camphor could be synthesized from turpentine derived from pine sap. The price of camphor by the 1930s was half that of 1908. Good for Vicks, bad for Japan. Enormous amounts of synthesized camphor were used in the early decades of the plastics industry, making celluloid and nitrocellulose lacquers.

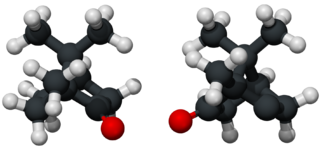

Enantiomers of camphor, naturally occuring (R)-form at left, mirror-image (S)-form at right.

When you get closer, you see that the primary columns of the torii aren't single pieces. They're built out of many irregularly shaped pieces.

The bracing columns and other beams are made from cedar. That's another aromatic species that's more water-tolerant than many woods.

The intertidal sections of the columns are home to many barnacles.

The columns rest on bases composed of many pine piles driven into the ground. The composite pilings have been solidified by granite and marble during more recent partial reconstructions.

Below you can see how the central shrine complex is built on a system of piers.

Prominent Buddhist facilities, a temple and pagoda, overlook the central shrine.

A pagoda, or tō in Japanese, typically has a religious function. It will be Buddhist in Japan, but might be Taoist in other countries. They are derived from the Buddhist stupa, a structure containing relics and used as a place of meditation.

This pagoda was built in 1407.

Pagodas traditionally have an odd number of levels. Western copies are often quite imprecise, with an even number of levels and other oddities.

The sōrin is the vertical shaft extending out the top of a pagoda. The kurin or the Nine Rings surround it. The hōju or hōshu, the Wish-Fulfilling Jewel, is at the very top of the shaft. In between the Jewel and the Nine Rings are the Water Smoke, suien, vertical perforated metal sheets set at right angles, and the Dragon Vehicle, ryūsha.

And, all of that is metal with sharp points and edges. It's as if these tall wooden pagodas were intentionally designed to be struck by lightning. Until lightning rods were developed in the 1700s, pagodas were frequently destroyed by fire.

Like Nara, Miyajima has bold, tame, sacred deer.

The washrooms have to have gates to keep the deer out. No one wants to try to use the toilet while several deer are wandering through.

After an hour or two, the tide was coming in.

Now I get to see the "floating gate" effect.

Eventually I returned by ferry and tram.

Whisky Bar

Back at the hostel, the staff recommended the K.C. Bar. It's just a couple of blocks away. There's a sign at the sidewalk by a small door. You go up a narrow staircase to a short hallway, and enter through a subtly marked door. It's a classy joint. Jazz is playing, the bartender is in a vest and bow tie.

I had a highball made with Hakushu single-malt whisky, of course from Japan. He started the glass with two large rectangular ice slabs, flawless rectangles. Then he added the whisky, lemon, and then soda.

Only Ireland and some US firms misspell it as "whiskey".

In Japanese it's rendered phonetically in katakana, as it's a foreign word.

ウイスキー

No letter "E", which is correct.

Amazon

ASIN: B001AQO400

Amazon

ASIN: 4805314095

Light snacks are available. This is four layers of cheese slices with nori, tissue-paper-thin sheets of seaweed of the red algae genus Pyropia, as used to wrap sushi and onigiri. I had this along with the second highball.

The bartender stacked it, cut it into small triangles, and served it with extra nori sheets, wasabi, and pepper.

Izakaya

Then I moved on to an izakaya for summer rolls and gyōza.

Then it was time to return to the hostel, to rest up for another day.

The above is specific to Hiroshima. Or maybe you want to explore other places in Japan.