Tōgō Shrine and the

Cenotaph of the Submariners

Tōgō Shrine

Tōgō Heihachirō was a gensui or admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy in the late 1800s into the early 1900s. He was one of Japan's greatest naval heroes, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet that defeated the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. He retired from the Navy in 1913, and was put in charge of educating Crown Prince Hirohito, the future Emperor.

He was widely called "the Horatio Nelson of the East" for his decisive defeat of one of the world's leading naval powers.

U.S. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz was a great admirer of Admiral Tōgō. In 1958 he helped to finance the restoration of the Mikasa, his flagship from the Russo-Japanese War.

There is a shrine to Tōgō and a nearby memorial to submariners, just off the busy youth-oriented Takeshita Street. The Cenotaph of the Submariners had caught my attention on a map.

Tōgō Heihachirō was born in 1848, when the Shōgunate still ruled Japan. He was 15 when he was part of a gun crew on a cannon defending the port of Kagoshima against a bombardment by the British Royal Navy. The daimyō or warlord established a navy the next year, 1866, and Tōgō joined it.

The civil war ended in the autumn of 1869, and the Emperor came to power in what was called the Meiji Restoration. Tōgō traveled to Yokohama to study English. In 1870 he was admitted to the new Imperial Japanese Navy Training School.

Below we're passing through the outer torii around the shrine.

Tōgō was one of 12 officer cadets selected to travel to Britain to extend their naval study. He trained with the British navy for seven years. He circumnavigated the world as an ordinary seaman on the British training ship Hampshire in 1875. Then he spent five months in Cambridge studying English and mathematics under the tutelage of the Reverend Arthur Douglas Capel. The Reverend was both a mathematics tutor and a curate at the Anglican church of St. Mary the Less in Cambridge, where Tōgō attended services during his time in Cambridge.

Tōgō returned to Japan in 1878 as a newly promoted lieutenant, an officer on one of the ships the Imperial Navy had commissioned from the naval shipyard in Portsmouth. By 1883 he was given command of his own ship.

He took part in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895. He commanded a cruiser, and rose to the rank of rear admiral by the end of that war. He was then appointed commandant of the Naval War College in Tōkyō, and in 1899, commander of the Sasebo Naval College.

This staircase leads up toward the side of the shrine, between banners with the maritime signaling flag "Z".

Tōgō is most known for his part in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, and especially the Battle of Tsushima. That was the only decisive sea battle fought by modern steel battleship fleets. It was in the era of steam and steel, but before naval air power led to over-the-horizon battles. It was also the first naval battle in which wireless telegraphy played a crucial role. And, the Z flag was important.

Tōgō had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1903. Meanwhile the Russo-Japanese War was looming, over competing Russian and Japanese imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean peninsula. Vladivostok's port was only operational during the summer. Russia was leasing Port Arthur in China as it could operate all year. Japan, however, saw this as Russia's encroachment into Japan's sphere of influence. Negotiations broke down in 1904, and the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the Russian Eastern Fleet at Port Arthur.

The Russian Baltic Fleet sailed out of Sankt-Peterburg, through the Baltic and North Seas, around western Europe, all the way around Africa, across the Indian Ocean, and most of the way up the east coast of Asia. After a voyage of more than 18,000 nautical miles and seven months, the Russian fleet arrived in poor shape. They had required about 500,000 tons of coal, but international law prohibited purchasing coal at neutral ports. So, the Russian Navy had to acquire a large fleet of coal supply ships. The ships' stores had also been a huge issue on such a long voyage.

Meanwhile, Port Arthur had fallen a few months before the Russian fleet arrived, meaning that they would have to continue to Vladivostok. The most direct route passed through the Tsushima Strait between Southern Japan and Japanese naval bases on the Korean peninsula.

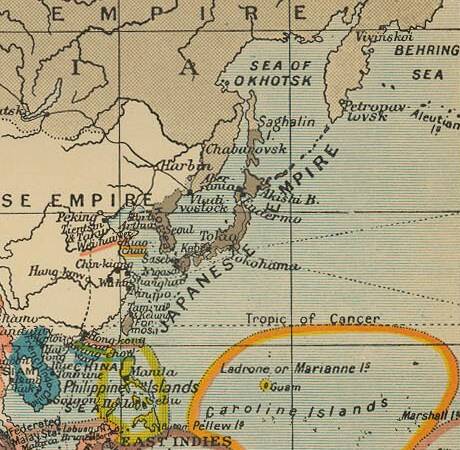

This world map from 1910 shows that the Tsushima Strait was probably the least bad option for the Russian fleet.

Below is the chōzubachi, the water reservoir for purifying yourself before entering. The shelter over it is the chōzuya or temizuya.

Tōgō famously sent a confident message to naval headquarters in Tokyo. The final sentence has become famous in Japanese military history:

In response to the warning that enemy ships have been sighted, the Combined Fleet will immediately commence action and attempt to attack and destroy them. Weather today fine but high waves.

A lone Japanese ship spotted the Russian fleet, and signaled Tōgō by wireless. In early afternoon the main bodies of both fleets spotted each other and prepared to engage. Tōgō ordered that the maritime signal Z flag be hoisted. The fleet understood that this one-character message carried the meaning:

The Empire's fate depends on the result of this battle, let every man do his utmost duty.

This was an echo of Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson's message at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, "England expects that every man will do his duty". Nelson had that signaled with flags as a series of 3-digit code numbers for words with the word D-U-T-Y spelled out.

| 253 | 269 | 863 | 261 | 471 | 958 | 220 | 370 | 4 | 21 | 19 | 24 |

ENGLAND |

EXPECTS |

THAT |

EVERY |

MAN |

WILL |

DO |

HIS |

D |

U |

T |

Y |

Tōgō's version was much more efficient, "Z" for the whole sentence.

Here it is — Tōgō-jinja or the Tōgō Shrine.

The shrine was being prepared for a wedding. Many people in Japan have a Shintō wedding ceremony, but then most have a Buddhist funeral.

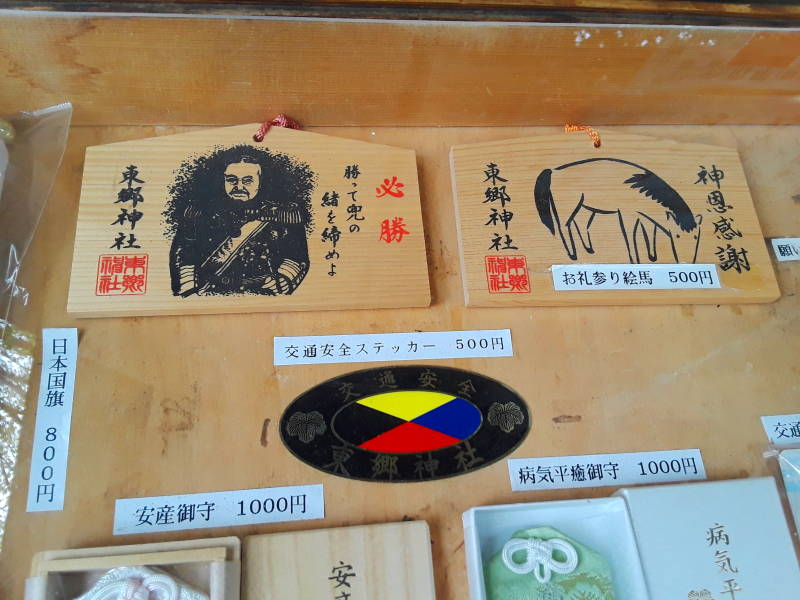

Because of Tōgō's victory over Russia, his shrine has become a place to seek victory or luck.

The Japanese fleet "crossed the T" of the Russians at the beginning of the encounter. Their battleships could fire broadsides while the Russians were limited to using their forward turrets only. The Russian battleship Oslyabya was the first ship sunk, 90 minutes after the battle began. Five more Russian battleships were lost by the end of the day, and they lost more warships overnight.

By the end of the battle, the Russians had lost over two-thirds of their fleet, including eight battleships and over 5,000 men. Only three Russian warships made it to Vladivostok, a cruiser and two destroyers.

The Japanese fleet lost just three torpedo boats and 116 men.

Barbara Tuchman argued in The Guns of August that the severe loss to Russian prestige and naval power contributed to the Central Powers' decision to start the First World War in 1914.

The quick victory over a major power, the world's third-largest navy at the time, may also have encouraged Japan's increasingly aggressive political and military establishment, leading eventually to the Second World War.

Tōgō was given the rank of Marshal-Admiral in 1913, roughly equivalent to Grand Admiral or Admiral of the Fleet in other navies.

He was put in charge of educating Crown Prince Hirohito from 1914 to 1924. Hirohito's grandfather was Emperor Meiji, the Emperor who had taken back power at the end of the Shōgunate. He had reigned from 1867 until 1912.

Hirohito's father, Emperor Taishō, then reigned from 1912 until 1926, at least officially. Taishō contracted cerebral meningitis in early infancy, and he had further neurological problems. Taishō carried out no official duties after 1919, and Crown Prince Hirohito was named Regent in 1921.

Admiral Tōgō was personally and publicly disinterested in politics.

The AmericanBlack Chamber Herbert Yardley

in Washington DC

He did eventually make some strong statements about the London Naval Treaty. That was understandable, as that 1930 treaty extended the conditions of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922.

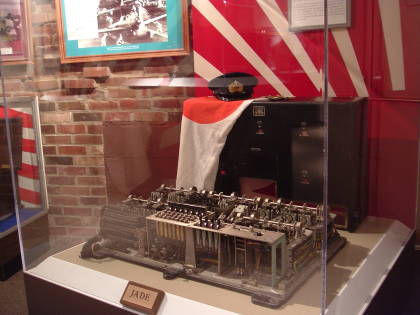

Japan had been at a severe disadvantage in the negotiation of that treaty, as the U.S. Black Chamber, led by Herbert O. Yardley, had been decrypting the Japanese delegation's communications with their government.

Here are more banners with the Z flag. There are conflicting legends about Tōgō's original flag, but apparently he took it with him to Britain in 1911 when he represented Japan at the coronation of George V.

He gave the flag to the HMS Worcester, the training which of the training school which he had attended. After the Worcester was retired, the flag was found and returned to the shrine in 2005.

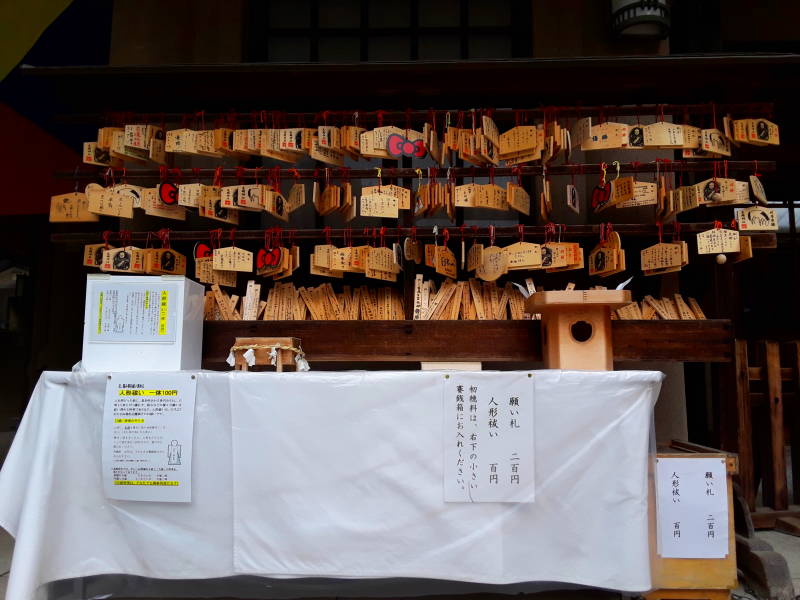

Some of these ema or prayer plaques depict Tōgō Heihachirō. You can also get a representation of the Z flag.

Buddhism

There had been popular interest enshrining the national hero as a Shintō kami after his death. Tōgō Heihachirō didn't want that, but it happened.

His mysticism was more along the lines of western figures like George Patton's belief in reincarnation and his former lives as soldiers. Tōgō's journal, which he wrote in English, includes: "I am firmly convinced that I am the re-incarnation of Horatio Nelson."

In 1989, an extreme Japanese left-wing group tried to destroy the shrine around the time of Hirohito's death and funeral. Hirohito had died on January 7, 1989, and his funeral was to be on February 24th.

On February 3rd, members of the group cut through the fence between the adjoining university grounds and the back of the main shrine building. They set off a bomb that caused quite a bit of damage, but didn't destroy the shrine as they had hoped. The same group set off a bomb on the Central Expressway through Tokyo on the day of the funeral.

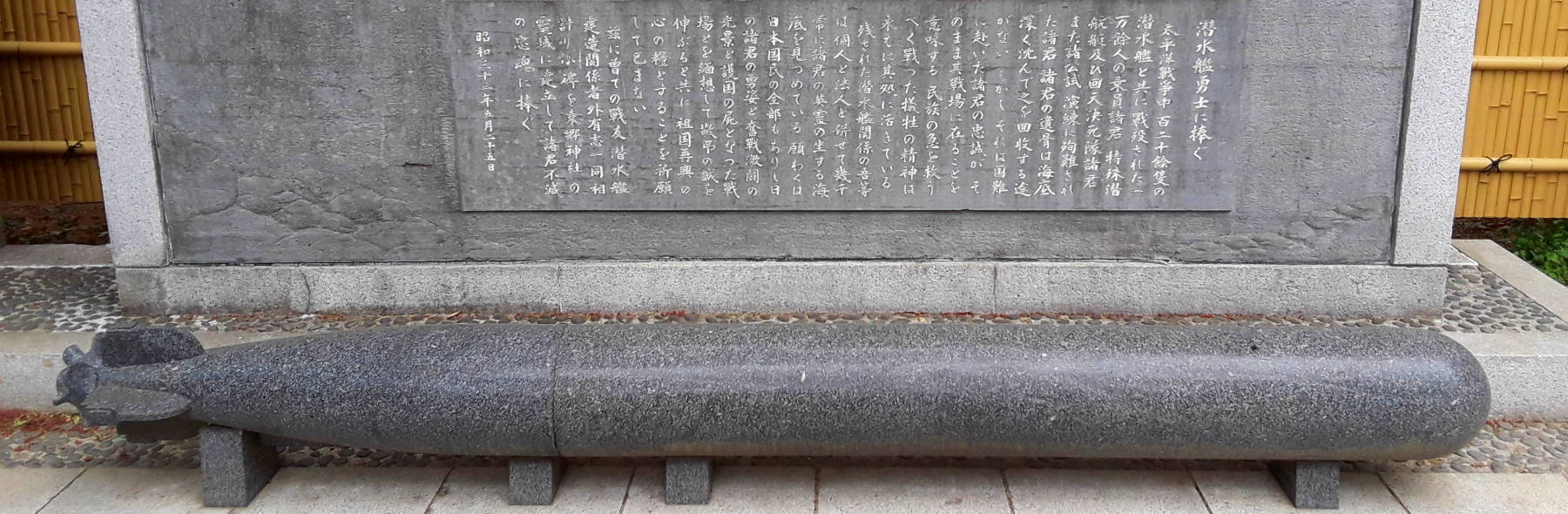

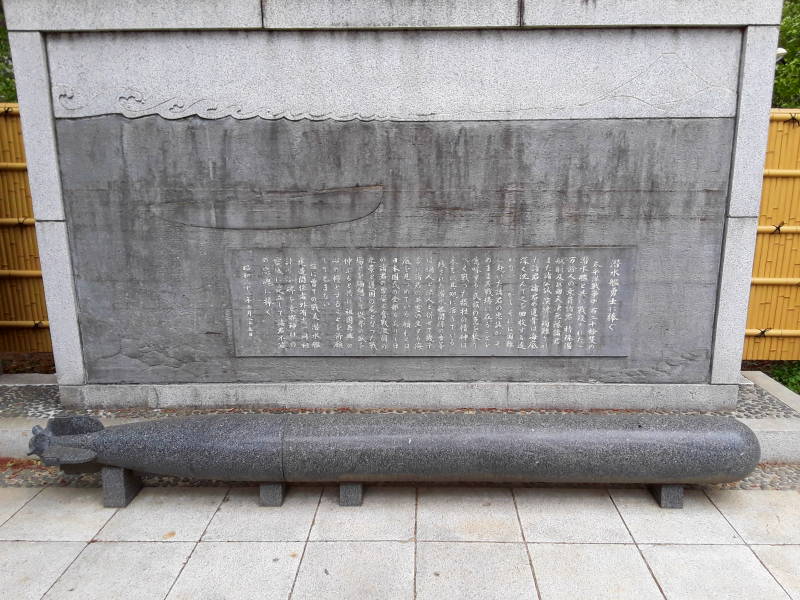

Cenotaph of the Submariners

This memorial to submarine crews lost at sea is directly across the lane from the Tōgō Shrine.

The traditional pair of guardian figures are depicted here with samurai style helmets.

The Imperial Japanese Navy purchased its first five submarines in 1904 from a newly-formed American company named Electric Boat. Yes, the company that still manufactures submarines for the U.S. Navy. Japan's new submarines were ready for operation by August 1905, a few months after the Battle of Tsushima. Before the end of that year, Japan had launched the first submarines they had built at Kobe.

They purchased some British submarines after World War One, and received nine German submarines as reparations.

By the start of World War Two, the Imperial Japanese Navy's submarine fleet was large and it included the widest range of designs of any fleet in the war.

At the large end of the range, the IJN had 41 submarine aircraft carriers. Most carried just one seaplane, but the I-400 class carried three. 122 meters long, these were the largest submarines in the world until the ballistic missile submarines of the 1960s. And, they carried enough fuel to circle the world one and a half times.

At the small end were the midget submarines, and the notorious Kaiten manned torpedo, a suicide weapon used in the final stages of the war.

However, with the diminishing supplies of fuel, loss of air superiority, and U.S. application of anti-submarine warfare tactics learned in the Atlantic, IJN submarines had less and less success.

IJN submarines sank about 1 million tons of merchant shipping on 184 ships during the war. U.S. Navy submarines sank 5.2 million tons on 1,314 ships, and Germany's submarines sank 14.3 million tons on 3,840 ships. A relatively small fraction of the Allied submarine fleet had largely destroyed Japan's merchant shipping connections, cutting off the movement of fuel oil and other supplies.

A few IJN submarines were sent on Yanagi missions, exchanging plans and examples of military technology, material, and skilled specialists with Nazi Germany.

There were five such missions. Just one of them made it all the way there and back.

Two made it to German-controlled territory, but didn't make it back.

Two were intercepted and destroyed on the outbound voyage, before reaching German-controlled territory.

The German Kriegsmarine ran a similar operation, with similar lack of success.

To the Taproom

In the below pictures, I'm making my way off the frantic Takeshita Street toward the shrine and cenotaph.

It would be absurd to tell you to go back the side street toward the pole with the visible electrical transformers and wires, because that describes pretty much everywhere in Japan.

But yes, there is such a pole back that side street. And another one two buildings further along.

The Harajuku Taproom is at the corner where you turn to the right toward the Tōgō Shrine. It's on the middle floor of the building.

Have some yakitori or something else to eat. As they say, to drink without eating would be British. Don't be British.