Ben Youssef Religious Complex

A Mîdhâ in the Form of a Qubba, a Madrasa, and a Mosque

The Ben Youssef religious complex

within the medina of Marrakech

includes what was once the largest Islamic school in Morocco,

the oldest mosque of Marrakech

which arguably remains its most important mosque,

plus an ablutions pavilion that is the last surviving example

of Almoravid architecture in the city.

As with the name of the city, spelling for speakers of French

or English varies widely —

Ben Youssef or

Ibn Yusuf or

other variations.

Similarly, is an Islamic school a madrasa,

a medersa, or some other similar spelling?

Yes, all of those and more.

However you spell it, there are some interesting

and beautiful things to see here.

Go north through the souqs of the

medina

from the

Jemaa el-Fnaa

for about 750 meters to find this area.

The Mosque

The Almoravid Berber dynasty built an empire spanning today's Morocco, southern Spain, and beyond, starting in the 1050s. The Almoravid chieftain Abu Bakr ibn Umar founded Marrakech around 1070 to serve as its imperial capital.

| Dynasties of Morocco | |

| Idrisi | 788–974 |

| Almoravid | 1040–1147 |

| Almohads | 1147–1269 |

| Marinids | 1269–1465 |

| Wattasid | 1472–1554 |

| Saadi | 1510–1659 |

| 'Alawi | 1631–present |

The Almoravid rulers never claimed the religious title of Caliph. Instead, they referred to themselves as Amir al-Muslimīn or "Prince of the Muslims" and formally accepted the religious authority of the Abbāsid dynasty Caliphs in Baghdad.

That was a cautious move by the Almoravids. Moulay Idress I had been an earlier Moroccan leader. He was killed in 791, apparently poisoned by an assassin sent from Baghdad by the Abbāsid Caliph Harun al-Rashid.

Things went well for the Almoravids, at least for a while. Their empire grew, including all of today's Morocco and extending significantly to the east and south from there. Plus, across the Strait of Gibraltar, more than the southern half of the Iberian peninsula, which was known as al-Andalus back then and Spain and Portugal today.

The Almoravid emir Yusuf ibn Tashfin built the first mosque in Marrakech in the 1070s, during the first decade of the city's existence. His son and successor Ali ibn Yusuf (or Ben Youssef) completed a new central mosque between 1120 and 1132. It was the largest mosque ever built in the Almoravid empire, 120 by 80 meters in size with a minaret now estimated to have been 30 to 40 meters tall. Marrakech grew around this grand mosque, and it and the surrounding souqs formed the core of the city.

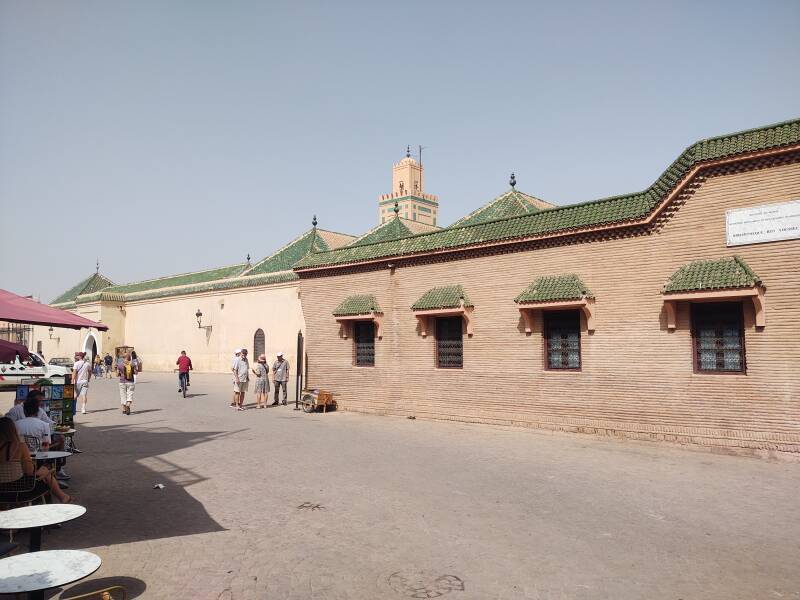

You come out of the covered souq on a lane known as Rue Azbezt, and then you see the Ben Youssef complex in front of you. Here is the library, and the minaret of the mosque beyond it.

That isn't Ali ibn Yusuf's original mosque. It's at least a replacement of a replacement because...

The Almohads were another Berber tribe. This is confusing — Almoravids first, then the Almohads. Both Berber, but violently opposed to each other.

Tashfin ibn Ali, the sixth Almoravid Emir and the last successful one, was fighting the Almohads along the Mediterranean coast in 1145 when he became besieged. He burned his military encampment and was on his way to join an evacuation fleet and escape by sea. But then he fell off a cliff and died.

His son Ibrahim ibn Tashfin was an infant. He was proclaimed ruler as soon as news of his father's death reached Marrakech.

Baby Ibrahim's uncle Ishaq ibn Ali, brother of the father Tashfin ibn Ali, quickly replaced the infant Emir as the eighth and last Almoravid Emir. But just very briefly.

The Almohads captured Marrakech in April 1147. They immediately killed Baby Emir and Uncle Emir and began erasing the legacy of the Almoravids in Marrakech. Other than a few short segments of the outer city wall, the Qubba el-Ba'adiyyin that we'll see further down this page is the only significant example of Almoravid architecture remaining in Marrakech.

The Almoravids were a Berber tribe from the desert. Other people called them al-mulathimun or "the veiled ones" because the men wore veils covering their faces below the eyes. The veil was practical for the blowing dust in the desert. The Almoravids insisted on wearing the veil everywhere, including throughout their new capital city, because it marked them as outsiders in the city. Everyone else was forbidden to wear this puritan garb, in order to make it clear who was the ruling class and also who was the most pious. Reading about the Almoravids, I realized that the same sort of thing still goes on today.

This man in a Walmart store in the U.S. state of Indiana culturally identifies as a Hunter, which explains why he is wearing mismatched hat, jacket, and trousers in three different camouflage patterns, the whole ensemble probably costing a total of US$ 150 or more. This picture was taken in early June, a time when it wasn't legal to hunt any game in the state. And, I'm not sure how suitable his sandals are for striding heroically through the forest. So, while he is signaling what he is, like the Almoravids he more importantly is signaling what he is not — he is not "city folk". In the U.S. you also see Military and Construction cosplay.

The Almohads were also a Berber tribe, but they made a point of mocking the Almoravids' veil as a sign of effeminacy and decadence. The Almohads wore different misplaced desert garb, you see. Now that the Almohads were in power, they could wipe out all traces of the wrong tribe wearing the wrong clothes.

The Almohad caliph Abd al-Mu'min announced that the Almoravid mosque had an orientation error, its qibla or direction of prayer pointed the wrong way. They either demolished the Almoravid mosque immediately, or abandoned it and allowed it to fall into ruin.

The Almohad empire grew until they controlled all of the Maghreb to a point well east of Tripoli and slightly east of Sicily and Malta by the 1150s, and north through all of Muslim Iberia by 1172.

The Almohads built the Kutubiyya Mosque at the southwestern edge of the city to serve as the main congregational mosque. It's the one you see prominently from the open square of Jemaa el-Fnaa. They also built the Kasbah Mosque for their new palace complex in the south.

On Jemaa el-Fnaa one evening I saw the crescent Moon setting above the minaret of the Kutubiyya Mosque that the Almohads built in the late 1100s.

However, the souqs of Marrakech were mostly around the old Almoravid mosque site, and so the area wasn't abandoned.

The Saadian dynasty took power in the 16th century and restored and extended this area of the city. The Saadian sultan Abdallah al-Ghalib, who ruled from 1557 to 1574, is said to have restored or rebuilt the Ben Youssef Mosque. However, no remains of the Saadian mosque or the Almoravid mosque that it replaced have ever been found.

The mosque that was here fell into ruin through the 17th and 18th centuries CE. It was completely rebuilt in the early 19th century by the 'Alawi sultan Suleiman, who ruled from 1792 to 1822. By that time the qibla, the proper direction of prayer, had drifted from due south toward the southeast, before finally becoming the local bearing toward the Ka'aba, the roughly cubical black stone structure in Mecca. In Marrakech, that's 91°, almost due east. And so, the new mosque is in a different alignment, and there is little to no sign of the mosque structures that came before.

Today's mosque is still called the Ben Youssef or Ibn Yusuf Mosque. That's its minaret below, beyond the dome of our next stop.

The Ablutions Pavilion

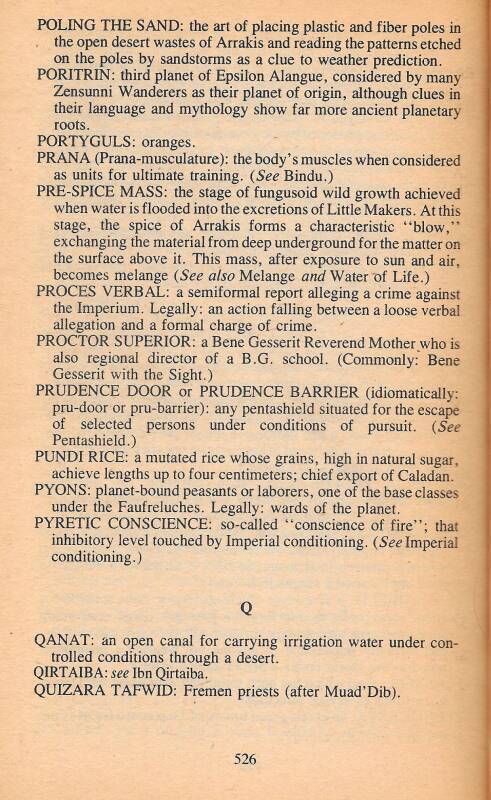

The Qubba el-Ba'adiyyin is a mîdhâ, a facility for the ritual washing required before prayer. The central basin is in a qubba, a domed structure. As always, qubba might be spelled for speakers of western European languages as qubba, qoubba, kobba, kuppa, and so on.

The Almohads had moved their attention to their large new mosques well to the southwest and south, and their kasbah or fortified palace complex to the south. The qubba wasn't destroyed, but it wasn't maintained. By the time the Saadians replaced the Ben Youssef mosque, the qubba had been mostly forgotten. Trash and blown-in dirt, plus demolition and construction debris from projects in this area, gradually built up to a depth of about six meters. This two-story structure was mostly buried.

French archaeologists cleared away the rubble and restored the qubba during the French Protectorate of 1912–1956. Then further restorations in the 1990s and the late 2010s further rebuilt the structure into the like-new state you see today.

Water channels flanked both sides of the qubba. Debris has been cleared away, but these structures are otherwise more or less as they were re-discovered.

The dome covers the central marble water basin.

The elaborate design on the arches and the interior of the dome mirror what is found in al-Andalus. The Almoravids had brought Muslim, Christian, and Jewish artisans from there to North Africa. They added further ornamental techniques from as far east as Baghdad.

All this washing required a good water supply. Around 3,000 BCE the Elamite kingdom in what came to be known as Persia developed a water transportation system called the qanat or the qanāh in modern Arabic, kārīz or kārēz in modern Persian or Farsi.

A qanat is a gently sloping tunnel connected to the surface via a series of vertical shafts used for maintenance. A qanat is resistant to natural disasters such as earthquakes and to intentional destruction in war. It can transport water over a long distance with minimal loss to evaporation even in a hot, dry climate, with no need for pumping.

The technology spread both east and west, picking up a variety of names. By the time it reached Morocco in the far northwestern corner of Africa it was called a khettara. A qanat or khettara system supplied this complex.

Qanat is one of the many Arabic words Frank Herbert used for his Dune books, although he described it as an open canal.

Maybe by the later books in the series, but not in the original.

The water storage system has also been restored, and you can visit it. All of this is part of the typical infrastructure associated with a mosque — a mîdhâ or ablutions facility for ritual washing; fountains to supply water to residents for cooking, drinking, and cleaning; a hammam or neighborhood bath; and a bakery that uses the fire that heats the hammam water to also bake bread.

Much more on the qubba, the cisterns, the latrines, and the khettara system

The School

The Marinid dynasty of 1244–1465 is known for its support of the arts and literature. They built several madrasa or schools across Morocco, including one built here during the 1331–1348 rule of Sultan Abu al-Hasan.

The Saadian ruler Abdallah al-Ghalib built a new madrasa in its place in 1563–1565, following the earlier Marinid architectural style.

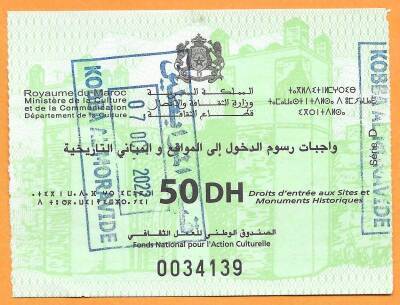

The madrasa operated until 1960, when it was closed down. It was restored and opened to the public as a historical site in 1982.

It's large, occupying a space about 40×43 meters. However, you approach via a narrow lane between multi-story buildings so, as usual, you don't know what is on either side.

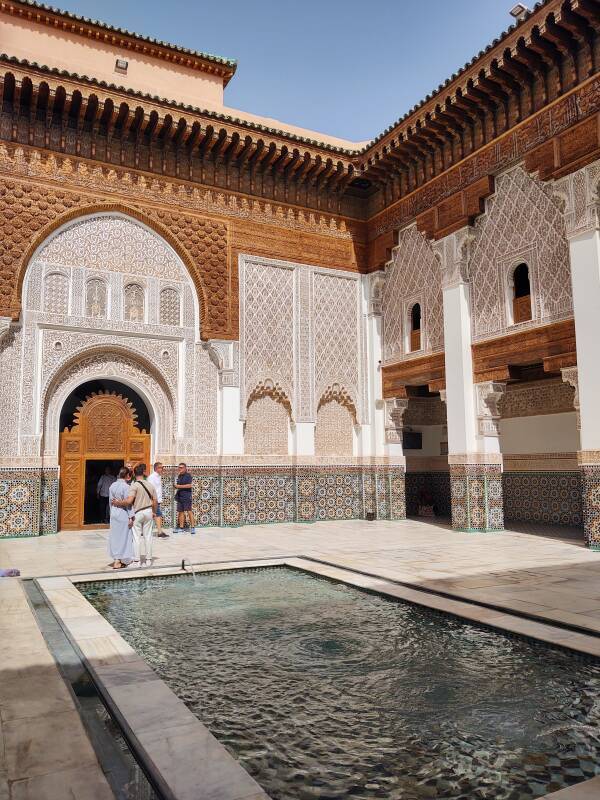

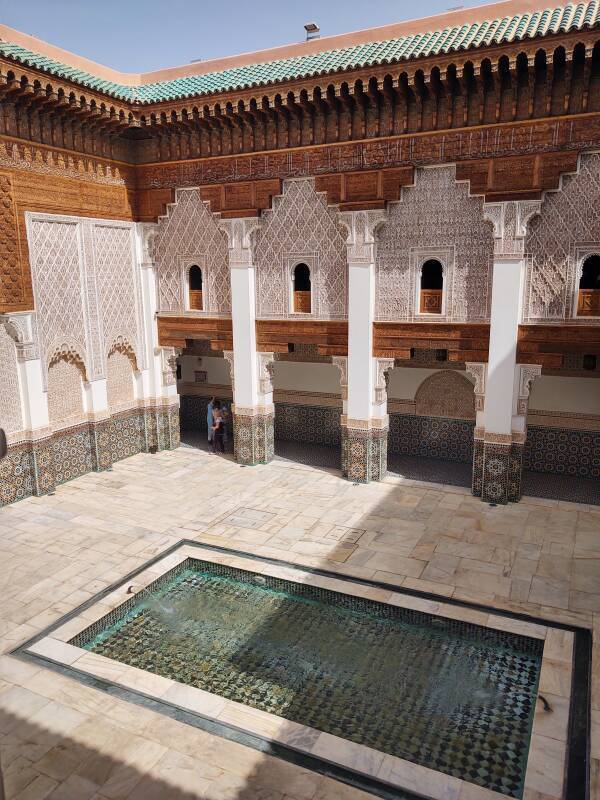

You enter through a single plain door, go down a narrow corridor into a small vestibule, and step through a door into the central courtyard.

The design is intended to inspire revelation and astonishment as you step into the large intricately decorated space.

Galleries along two sides provide spaces for classes to gather.

Student dormitory rooms surround the courtyard on the ground level and on upper levels.

There is zellij geometric tilework up to about eye level, one or more rows of painted and carved Arabic devotional text, and carved stucco and cedar wood above that.

One end of the courtyard has a doorway into a large chamber that served as a prayer hall. A mihrab or niche indicates the qibla or direction of prayer.

Going upstairs into the dormitory area, you see that open wells provide light and ventilation.

Sturdy doors open into students' rooms.

This one is on two levels. A steep staircase leads up from the entry.

The madrasa has 130 dormitory rooms, in which up to 800 students lived. That works out to six students in most rooms, seven or more in some larger ones. In its time, it was the largest madrasa in Morocco.

Like the traditional guesthouse where I was staying in the medina, the light wells are simply open to the sky. It's Marrakech, it doesn't rain a lot here. About one inch per month from mid-October through April, with very little over the summer.