The Kasbah of Meknès

The Kasbah of the Sultan Moulay Isma'il in Meknès

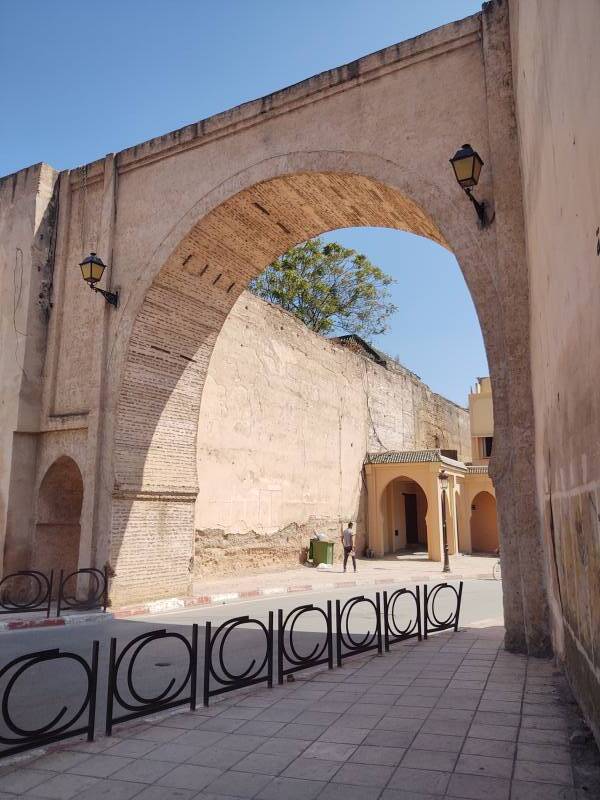

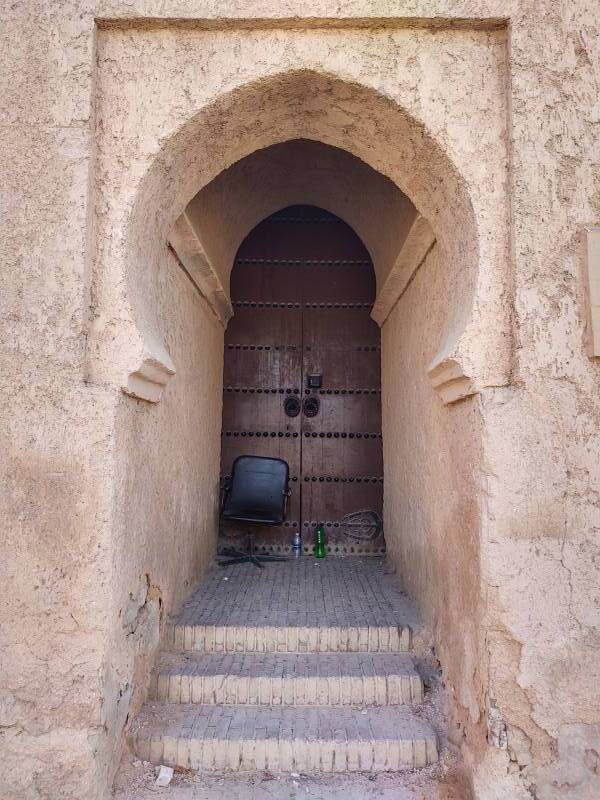

Above is a view of a small part of the fortified walls of

the Kasbah of Moulay Isma'il

in Meknès.

European ambassadors in Meknès wrote that

the fortification walls alone were more than twenty-three

kilometers long.

Moulay Isma'il Ibn Sharīf

ruled as the Sultan for 55 years,

from 1672 until his death in 1727.

During his 81 years of life he fathered

over 1,000 children with at least 500 concubines.

Europeans described him as cruel, merciless,

greedy, and untrustworthy.

One writer reported that he had over 36,000 people killed

during a 26-year period of his reign.

Another reported 20,000 assassinations during

a twenty-year period.

His kasbah

or inner fortified complex was massively designed.

The outer defensive walls, built from rammed earth,

were seven meters thick.

Especially near the medina, the old city where most

of the population lived, the kasbah and its palaces were

contained within two or more lines of defensive walls.

Moulay Isma'il didn't trust outsiders,

nor did he trust the people in his city.

He had an older kasbah area destroyed in order to improve

the defense of the kasbah against attack from the medina.

The resulting open space is known as

Place el-Hedim,

named "The Rubble" as this was where the demolished

material was piled.

Here it is when I visited, looking toward the medina.

Rue Dar Smen, a major street, runs east-west along the north walls of the kasbah, crossing the south end of Place el-Hedim.

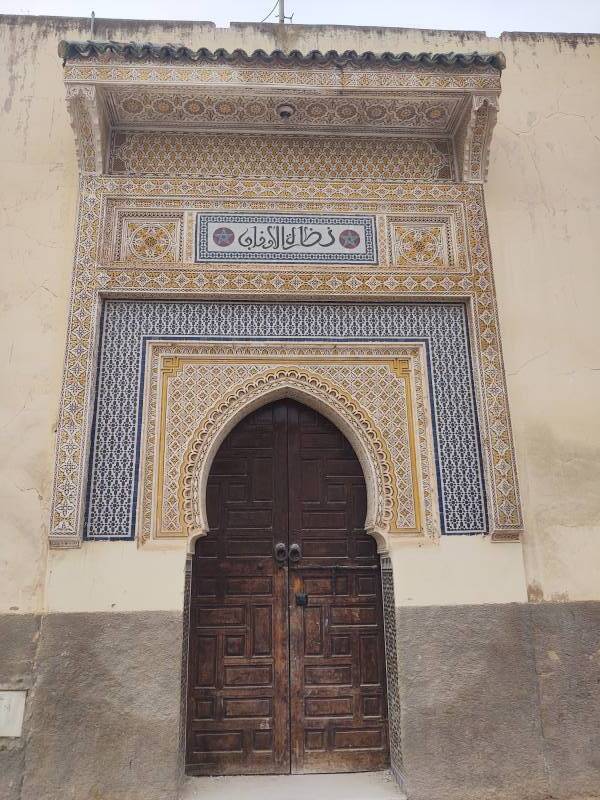

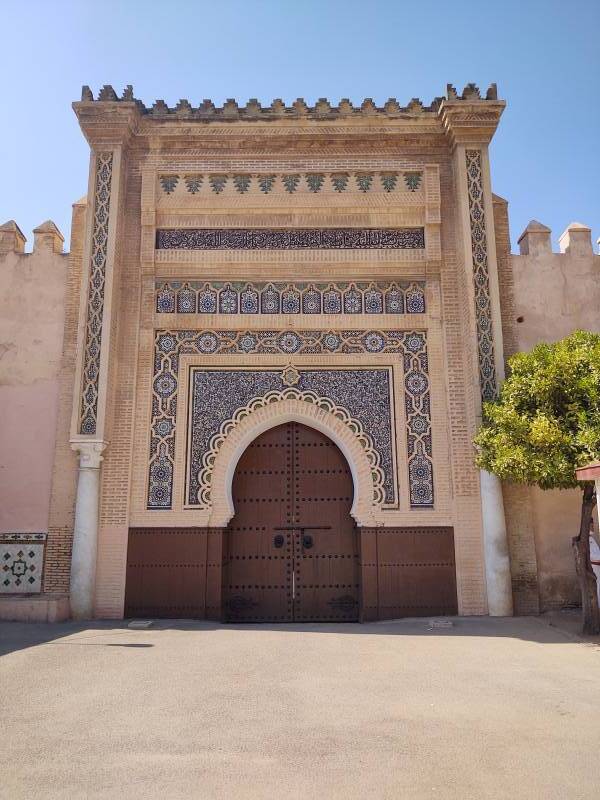

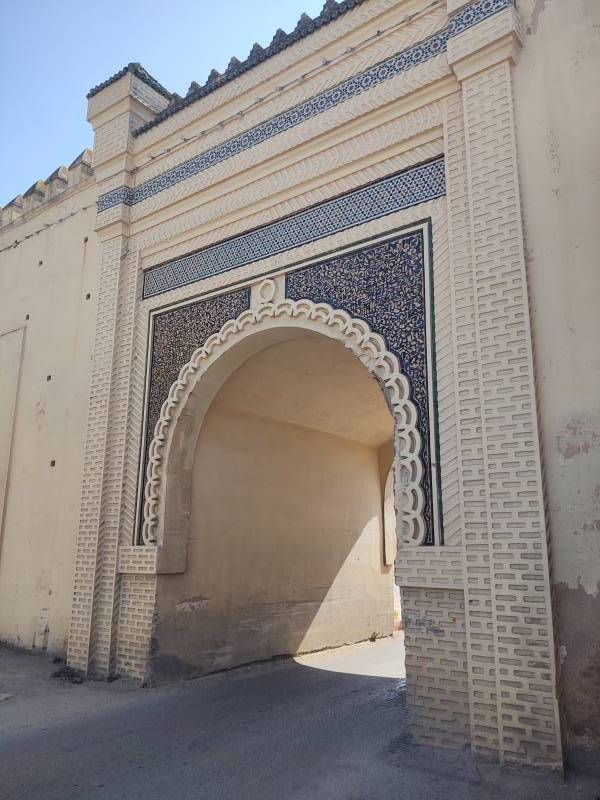

Large elaborately decorated gateways provide controlled access to the kasbah.

Meknès is over 5 degrees west of London. But these enormous sand-colored fortification walls pierced with elaborate portals appeared to me like something out of Central Asia, or maybe the Hyborian Age as described by Robert E. Howard.

Below is the Bab Jama' en-Nouar, which is the smaller and less ornately decorated gate along this section of wall. The larger and more elaborate Bab Mansur al-'Alj was undergoing restoration when I was there, covered by scaffolding and construction sheeting.

There were so many repair and improvement projects underway when I visited Morocco. They were restoring ancient monuments, improving highways through the mountains, and building new high-speed rail lines.

These gates have large horseshoe arches forming keyhole-shaped openings. The ornate decoration combines Moroccan style geometric patterns with some details the Romans lifted from Ancient Greece, probably by way of the ruins of Volubilis. The Moroccan geometric designs include colorful zellij or mosaic tilework.

Bab Lalla Aouda provides vehicle access to Place Lalla Aouda, now a large public square just inside the outer walls. It was once the parade ground where official ceremonies could take place.

dar means "house".

Dar al-Kebira is just inside the outer walls and across Place Lalla Aouda. It was the first of Moulay Isma'il's palaces to be completed. It had hanging gardens modeled on those of Babylon. That was typical of Moulay Isma'il, commission a palace modeled after one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The kasbah's fortifications were the most elaborate on the side where it faced the medina, indicating that Moulay Isma'il saw the city's inhabitants as a potentially greater threat than forces from outside. The palace of Dar al-Kebira was triply protected, within three nested perimeters of seven-meter-thick walls. These gates would be "bent", meaning that you had to pass through two ninety-degree turns on your way through the thick wall. Large mobs with battering rams simply couldn't run through a bent gate.

Moulay Isma'il did everything on a grand scale. He also had high expectations of what he could accomplish through the mail.

He sent a request to France for the hand in marriage of one Mademoiselle de Nantes, one of the many illegitimate children of King Louis XIV of France.

He also sent several letters to James II of England, offering him aid after he had been deposed in 1688 and trying to convert him to Islam.

He didn't get a French wife or convert the English king, but he kept sending letters.

Bab Filala leads to the south out of the southwest corner of Place Lalla Aouda.

Continuing further you pass through this double archway onto Avenue Bab Marrah, running past the Mausoleum of Moulay Isma'il and further into the kasbah complex.

Some of the gateways to the sides lead into areas now used for small businesses and residences. Ahead is Bab ar-Ra'is, a gate through a massive bastion over the asarag or avenue at a corner of the fortification walls.

The walls are seven meters thick, but the fortifications at the corners are much larger yet. A long passage takes you through the fortification at Bab ar-Ra'is.

The avenue exits the gate and runs in a straight line for 900 meters between two mostly blank walls. There's now a residential district over the wall to the left. But the wall to the right encloses Dar al-Makhzen, the Royal Palace of Meknès, where the King stays when he's in town.

It's a large space. The first two-thirds, closest to the medina and toward the northwest, has been home to a nine-hole golf course since 1967.

There's a nice fountain and gateway along the Avenue Bab Marrah.

Rounding the east end of Dar al-Makhzen takes you past Bab al-Makhzen, the main gate into the King's palace.

Then you continue through more large courtyards, past more elaborate gateways.

Eventually you reach another area with massive granaries and storage facilities for food and water. Moulay Isma'il claimed that his kasbah could hold out for ten years under seige.

The palace infrastructure was highly developed. Its water supply system drew water from underground, stored it in a large reservoir, and distributed it throughout the kasbah via canals and underground terracotta pipes. It was at least a century ahead of systems found in European palaces and cities.

The infrastructure included the Heri es-Souani, a large complex of food storage silos.

Adjacent to the Heri Souani was the Dar al-Ma, the House of Water or the House of the Ten Norias (or water wheels). That used a mechanical system of buckets on chains turned by large wheels, lifting water up from an underground aquifier.

That water was directed into a large open reservoir, the Sahrij Souani. The reservoir is about 320 by 150 meters in area, 1.2 meters deep on average.

The reservoir was empty when I visited. Moulay Isma'il's plans were always a little more grand than what was needed, and what could be sustained.

Moulay Isma'il died in 1727 and his sons fought for control of the country. A severe earthquake in 1755 damaged the huge palace complex in Meknès. By 1757 his grandson, Sidi Mohammad III, had moved the capital to Marrakesh.

Details were forgotten or distorted. Many of the food storage facilities came to be described as "prisons", and the legends grew until they supposedly held tens of thousands of Christian prisoners. Other storage facilities were mislabeled as stables. Legends about a mad sultan with tens of thousands of horses and tens of thousands of Christian prisoners forced into slave labor to build his palaces remain popular, so they persist.

Now I will visit the Mausoleum of Moulay Ismail, within his vast kasbah.

dar means "house".