Jebel Zagora

Jebel Zagora

It was late in my trip to Morocco

that I went into the desert to Zagora

and then beyond there to M'Hamid el Ghizlane.

As I had expected, and had planned for,

by this time I wanted to relax and

not maintain a full agenda every day.

It was time to quit drinking from

the firehose of Moroccan history.

I owned the

Lonely Planet book for Morocco,

among the most useful titles remaining in their

series now aimed more at luxury travel,

and had borrowed two guide books from the local library

for pre-trip planning.

Each of them mentioned Zagora,

and then went on to say that it didn't have much

in the way of attractions.

That was what I was looking for.

They mentioned Jebel Zagora,

a mountain a short (or medium, or longer yet) distance

outside town.

All of them described it as tiring and not really

worth the trouble.

Well, all of that just encouraged me!

I would stop in Zagora for a few nights on the

way to M'Hamid, and I would check out this

maligned geological feature.

It was great!

The guidebooks' confusion over the distance

comes from the presence of

a chain of peaks approximately the same height.

Some visitor has used Google Maps to label

a point along that chain as

The Jebel Zagora,

close to a not-so-helpful landmark purporting to

indicate the only desert-like location in the region.

The desert is documented as only operating

between 9:00 AM and 5:00 PM daily.

Ah, the wonders of unsupervised crowd-sourced references.

Google Maps doesn't let you share a map with the Terrain layer or displayed at arbitrary scale. And so, here's a screenshot.

The bridge over the dry Draa wadi or dry river bed is around 710 meters elevation.

The peak closest to town is at 971 meters.

My innkeeper had told me about the obvious turnaround point where someone has abandoned a project to build a hotel. That's far enough. It's at about 850 meters elevation, Sure, you can continue most of the way to the peak, but you'll just be a little more hot and tired and thirsty and you can't really see any more from there than what you can on the way up.

Despite his efforts, I could not be talked out of going to Jebel Zagora. But I was easily convinced to only go part of the way up it.

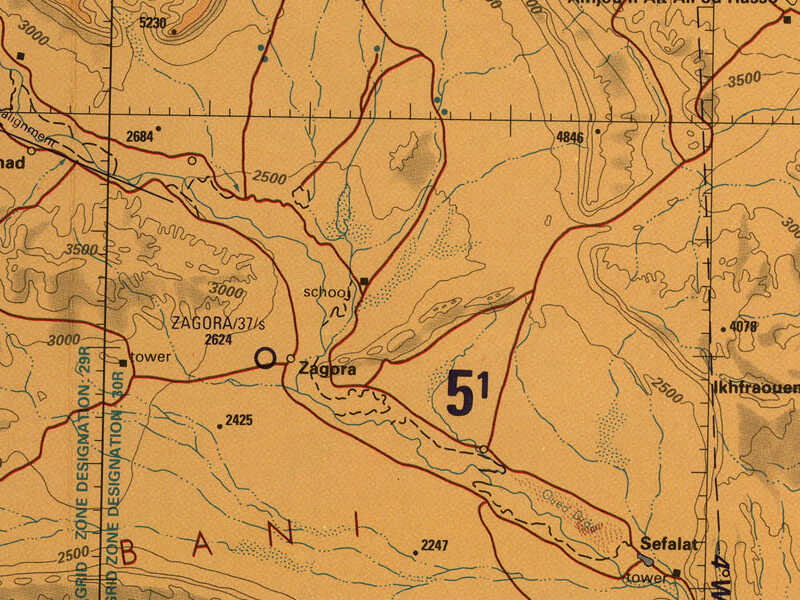

This map, despite being a 1:500,000 chart for high-performance aircraft and thus somewhat vague, shows the chain of small peaks running east-northeast from Zagora.

Small portion of 1:500,000 Tactical Pilotage Chart TPC H-2A from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

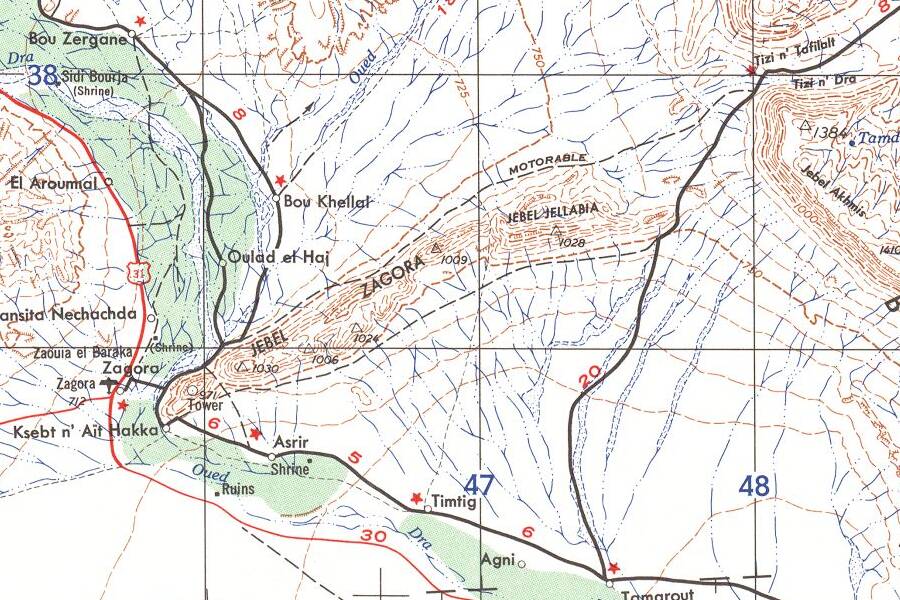

This 1956 1:250,000 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers map finally explains things. Yes, that series of peaks — 971 meters closest to town, then 1030, 1006, 1024, and 1009 meters — is collectively Jebel Zagora, and then the 1028 meter peak at the far end gets its own name of Jebel Jellabia.

Small portion of 1:250,000 map H30-5 from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

To the Mountain

I had a big breakfast at my guesthouse (all breakfasts are big in Morocco, in my experience) and started walking south along the N9 highway that runs through the center of town. I would go that way in a few days.

Before long I reached a traffic circle where Jebel Zagora appears in the distance. I needed to continue to the right as seen here to reach the south end of town, then cross the Draa wadi, and reach the mountain.

Having crossed the Draa, the road passed date palm groves.

The N9 road, which I had been following, turns off to the southeast, toward its end one hundred kilometers to the south at M'Hamid el Ghizlane.

I turned left onto the N12 road, which runs roughly west-east through Zagora, and started making my way around Jebel Zagora. Or, perhaps, around the westernmost peak of the chain of peaks known as Jebel Zagora. Whatever.

There was a nice view back to Zagora.

Looking ahead, I saw that the road was paralleled by a large irrigation ditch. The two-lane paved road I was walking along was the track marked "motorable" on the 1956 map.

To my right the terrain rose to Jebel Zagora, the 971-meter peak closest to town.

The second peak in the chain has a much more dramatic appearance, and is obviously a volcanic plug. At 1030 meters it's the tallest of the chain.

Yes, this is an area where you might come across camels roaming freely.

I turned south off the road and began passing between the two peaks.

In the picture above you can see the abandoned hotel project part way up.

A chain of mountains was visible about 30 kilometers to the south.

Jebel Bani, visible to the left below, is about 25 kilometers to the east.

Much closer, you can see a wall part way up that conical plug. It's a vertical volcanic dike, where magma flowed up into a crack and solidified.

Turning left, looking northeast, you see the large date palm oasis east of Zagora.

Looking north, you are looking up the Draa valley. The wadi and the date palms are right of center, Zagora to the left. Ruins of fortifications are down the slope from this viewpoint.

The sloping lava layers are clearly visible alongside the track leading to the summit.

Beyond the wadi to the southwest is more barren terrain.

Nearing the unfinished hotel I had a view back along the chain of volcanic peaks toward Jebel Bani.

The Draa wadi continues away to the southwest. Several guesthouses line the base of the mountain.

They had made a good start on building a hotel at this overlook about halfway up the mountain.

Looking back over Zagora you see that it is fairly large.

The valley and the road disappear to the northeast, leading toward Ouarzazate and, eventually, Marrakech.

The view north from the overlook shows how wide the Zagora oasis is.

The frequent winds lift very fine dust into the air. This view is toward the south-southwest.

I decided to stop here and not continue to the peak. Given that it's home to telecommunication infrastructure, you probably can't get all the way to the top, and getting close to it might upset the authorities.

Wind at higher altitudes moved the clouds and their shadows. Wind at ground level picked up a layer of dust of varying thickness.

When I arrived in Zagora, my innkeeper asked what I wanted to do. Yes, yes, in addition to my odd interest in Jebel Zagora. Maybe a 4x4 trip to some ksar settlements?

That's interesting, but I mainly just want to relax for a few days.

He asked if maybe I was there to search for meteorites.

What?

Yes, Zagora gets a significant number of visitors who are there to search for meteorites. It's not as if Morocco somehow gets more meteorites striking the ground. But, with large areas of stony desert in which the local rocks are not at all like meteorites, Northwest Africa, meaning Morocco, Western Sahara, and Algeria, is one of the more rewarding places to hunt for them. Plus, Morocco does not have regulations about exporting extraterrestrial material found lying around. At least not yet.

The guesthouse where I stayed is home to meteorite hunters from time to time. Some of them, I was told, have shown up annually for some time.

And then, just two months after I returned home to West Lafayette, the Special Collections department of Purdue University's library, just a few blocks up the street from my home, put on an exhibit related to the 50th anniversary of the last (so far) U.S. mission to the Moon. That was Apollo 17, in 7–19 December 1972. The library has a lunar meteorite. That's a stone that was sitting on the Moon minding its own business when it was knocked loose by a meteorite impact there. It flew into space as a meteoroid and then was attracted to the nearby gravitational well of the Earth. It crashed to ground on the Earth as a meteorite in an area loosely regarded as the Western Sahara and thus kinda-sorta-Moroccan, more or less.

Sorry about this recent historical rabbit hole when I claimed that there wouldn't be one, but...

As I went on at some length on the pages about Tangier, Morocco had been ruled by a series of sultans who were mostly of Berber tribal background, from the time the Romans gave up on this hot and dusty far corner of their empire until (really simplifying here) the late 1800s into the early 1900s. The Spanish had become interested in the far northern and generally southern parts, and the French in the middle part. Spain and France had recently updated their military hardware, and the Morocco was going through a series of inept sultans. Then there was:

- German sabre-rattling and recklessness,

- French Protectorate of Morocco and Spain's rule of a far northern strip plus a large southern chunk,

- World War I,

- Roaring 1920s,

- Global Depression and the 1930s,

- World War II (in which Tangier and not Casablanca was the home of espionage and intrigue), and then

- Ten years of the world catching its breath.

After 1956 there was the independent Kingdom of Morocco with a long tradition of French control of most of it, and to its south, Western Sahara with its long tradition of Spanish control.

Morocco has huge phosphate deposits, especially in the south. And, by analogy with the countries surrounding the Persian Gulf, some 6,000 kilometers to the east, Europeans frequently assume that hot sandy desert with Islam-practicing inhabitants must have oil to be seized.

Spain had dreams of wealth and power, and seized control of Western Sahara. It was called Spanish Sahara for a while. Spain realized that there was no oil and only very little phosphate compared to Morocco. There was some of the world's most inhospitable climate, with daily high temperatures of 43–45 °C in July and August. The small population had lived in the harsh desert for centuries, and were willing to fight would-be European colonial rulers.

Spain handed control over to joint administration by Morocco and Mauritania in 1975. A three-way war began between those two countries and the Polisario Front, based in Tindouf, Algeria, which considered the territory to be the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic or SADR and claimed to be its legitimate government in exile.

Mauritania surrendered its claim in 1979, and Morocco began establishing control over most of the territory. Morocco describes it as its Southern Provinces.

Morocco began building an enormous sand berm, the Moroccan Western Sahara Wall. The first version of the wall, built in 1980–1982, protected the phosphate mining operation at Bou Craa, in the territory's northwest.

Western Sahara's phosphates reserves are less than two percent the size of those in Morocco, but they're still quite large. Bou Craa is a deposit of over 1.7 billion tons of phosphate. The operation produces around 3 million tons per year, 10% of Morocco's total production. The phosphate is transported to the coast by a 100-kilometer conveyor belt, the longest in the world.

From 1980 to 2020 Morocco built more sections of the Western Sahara Wall, extending the enclosed territory further inland and south. The wall is now about 2,700 kilometers long, and is made from sand and stone walls or berms about three meters high with bunkers, fences, and the longest continuous minefield in the world. Morocco controls the two-thirds of the territory to the west of the wall, and claims the inland third claimed by the Polisario Front as the SADR.

Western Sahara is, by far, the largest of the United Nations' list of non-self-governing territories. and other than Gibraltar it's the only one that isn't a fairly small island.

In 2020 the U.S. became the first, and so far the only, United Nations member state to recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. This was in exchange for Morocco's establishment of diplomatic relations with Israel.

Meanwhile both desert areas within Morocco itself and the Moroccan-controlled two-thirds of its all-desert "Southern Provinces" remain prime territory for hunting for meteorites. Here's one that a collector donated to Purdue University.

Lunar meteorite Rabt Sbayta 006, found in the Western Sahara in 2016, donated by the Boudreaux family to the Purdue University Libraries Special Collection.

The library describes it as:

Content description:

One framed slice of lunar meteorite Rabt Sbaya 006, (Lunar feldspathic breccia), 7"×7" framed and one stone of lunar meteorite Rabt Sbaya 006, approximately 2.5" x 1"×1". An additional framed slice of lunar meteorite Rabt Sbaya 006, 4.5"×4.5" was donated to the Dauch Alumni Center

Provenance:

Gift of Terry Boudreaux, Gail Koziara Boudreaux, Christopher Boudreaux, and Evan Boudreaux, MS '20, Technology Leadership & Innovation. Meteorite Rabt Sbayta is listed in the Meteoritical Bulletin Database as being found in the lunar meteorite strewnfield near Gataa Sfar in 2016. Purchased by Terry Boudreaux from a Moroccan meteorite dealer in 2017.

"Strewnfield" means that the meteor broke up while entering the Earth's atmosphere and a cluster of fragments struck the surface as meteorites.

The Rabt Sbaya 006 meteorite weighed 4.81 kilograms when it was found in 2016 near Rio de Oro at 24.24 °N, 14.75 °W, The Meteoritical Society within the Lunar and Planetary Institute has a page with its specifics. In 2018 the Meteoritical Bulletin reported the 1,868 meteorites approved by the society's Nomenclature Committee in 2017. Of those, 48 were Lunar meteorites and 19 were Martian meteorites. Many of the meteorites catalogued each year were found in northwest Africa.

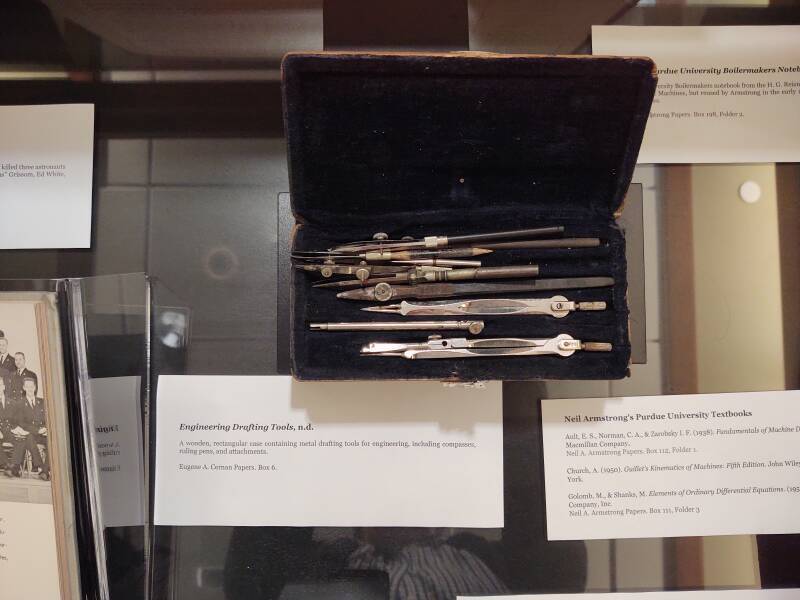

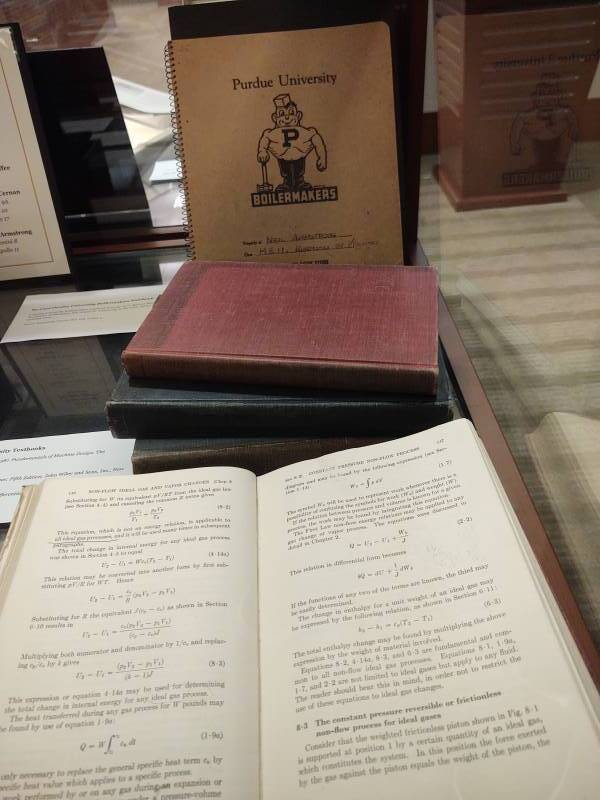

A nearby case during that special exhibit held the drafting tools of Gene Cernan (B.S. Electrical Engineering 1956, Gemini 9A, Apollo 10, Apollo 17) and some textbooks that belonged to Neil Armstrong (B.S. Aeronautical Engineering 1955, Gemini 8, Apollo 11)

Now, back to Morocco and further southeast into the desert.