Palaikastro Area

To the Minoan Port City of Roussolakkos

I was on my way to a Minoan port city.

We call the city Roussolakkos,

although we don't know what the Minoans called it.

Or, for that matter, what they called themselves!

"Minoan" is an early-20th-century fanciful label applied

by Sir Arthur John Evans when he first began excavating

the complex outside Heraklion.

"Obviously this was

the palace of King Minos!",

he hastily concluded.

Meanwhile "Roussolakkos" is likely a Greek spelling of an

Italian name applied by the Venetians when they ruled Crete.

Red something-or-other.

The abandoned ancient city is Roussolakkos,

and the nearby village and its surrounding district

is Palaikastro.

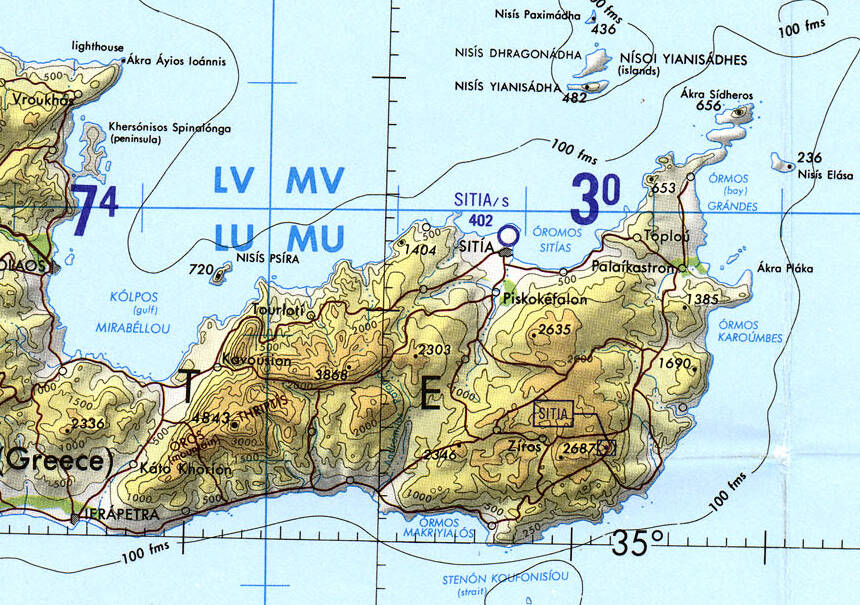

You can see Palaikastro on the map below,

a short distance east of Sitia on the far eastern coast

of Crete.

Officially the name ends -n or -ν,

Palaikastron or

Παλαίκαστρον.

Roussolakkos is on the coast, east-southeast of Palaikastros.

Tactical Pilotage Chart G-3C from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

Names are confusing here, and spelling them in the Latin script used for English gets more confusing. The town's name comes from "old fortress", but is the first part Palai, Palae, or even Pale? I'll spell it Palaikastro as that's a letter-for-letter match to the Greek, without the silly notion of "In order to write about this in English, we must spell everything in Latin as the Romans did."

The city-state of Venice controlled Crete from 1205 to 1669, insisting the whole time that everyone must worship God in Latin and do everything else in Italian. That program had very little success.

Now you have people annotating Google Maps in various languages with their own notions of how to spell Greek as if it were Latin. "Arkæologiske udgravning af Minoisk" and so on, the English aren't the only people with a Latin fixation.

Arriving at Roussolakkos

Drive through the village of Palaikastro and on east toward the coast, to a road intersection at 35.19868° N, 26.27432° E. The large outcropping seen below will be ahead and to your left. This is the view looking back at it from the entrance to the site.

This 65-meter-tall outcropping is what's called the palaikastro or "old fortress". The Venetians built a fort with walls and turrets on the top. There probably had been a Minoan fortification up there during the Bronze Age.

Gunpowder and cannons were invented in China in the 9th century CE, reached the Muslim world in 1240–1280, and Europe around 1280–1300. At that point this was no longer an adequate fortress. There had been very little space as the top is a narrow ridge and not a plateau, and there's no source of water. You couldn't live up there, and it had never been much of a fort. But it had been useful as an observation point. The Venetians disassembled the fortress, hauled its building stones back down, and used them to build other structures. In 1668 when Venice had mostly lost control to the Ottomans, the Turkish traveler Evliya Celebi wrote that it was just ruins.

You want to turn right and then drive parallel to the beach for about 150 meters and then turn right to reach the site. The signs are confusing, but this is the entrance.

This region was a center of trade during Minoan times, and this was one of the major ports. The town was occupied during what archaeologists classify as Early Minoan IIA through Late Minoan IIIB, approximately 2900–1100 BCE. It was especially prosperous through the Late Minoan period of 1550–1220 BCE, when the Mycenaeans were replacing the Minoan civilization.

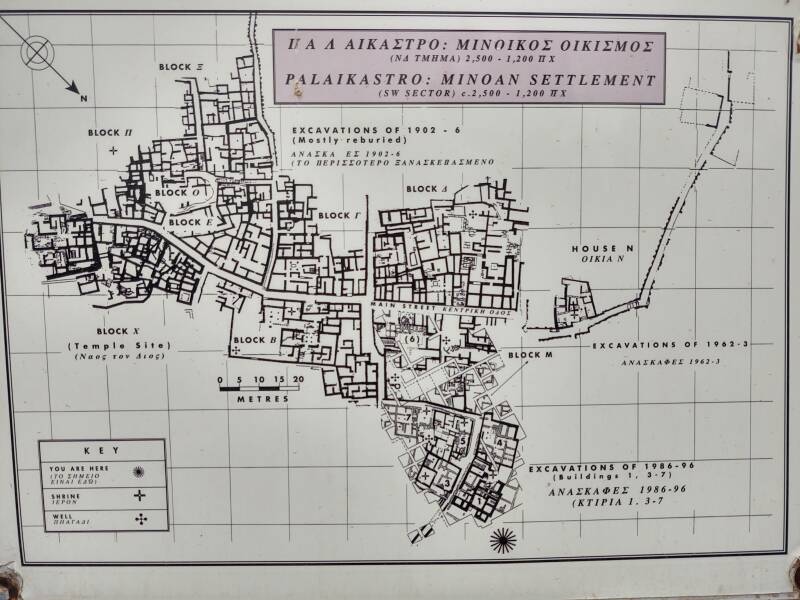

The town grew to cover an area of more than 50,000 square meters or 5 hectares, making this the largest Minoan town discovered. A grid of roads divided it into nine districts. Houses along the main street were built to elaborate designs. This was a sophisticated city.

The maps at the site show much more than you can see today. Archaeologists from the British School at Athens excavated here in 1902–1906, then again in 1962–1963, and then from 1983 onward. The earliest excavations have mostly been reburied.

There was no surrounding defensive wall. The Minoan era was relatively peaceful, although it wasn't the idyllic matriarchal paradise that Evans dreamed of and claimed to have found. The Mycenaeans were militarized, "the Greeks" in the Trojan War.

There was a general collapse of civilizations all around the eastern Mediterranean during the period 1200–1150 BCE. That was also the end of this being a prosperous port.

Entering the site you see some of the more elaborate ruins built with mud bricks under a protective cover. Mount Petsofas in the background had an open-air sanctuary at its 255-meter peak.

A map near the entrance shows the surroundings of Roussolakkos.

The Minoans seem to have had two gods ranked above all others, a Mother Goddess and a male youth with which she had both a mother-and-child relationship and a "holy marriage" relationship. Very Mesopotamian.

Those paired deities seem to have been associated with vegetation and fertility, and the seasonal cycle of death and rebirth. The youth may have been associated with the Orion constellation, visible through the winter. The vegetation god was gone, up in the sky until spring.

When the Mycenaean Greeks arrived in Crete around 1500 BCE, they identified the male deity as their own supreme deity. This was a precursor to Zeus, although they didn't call him by that name. To the Mycenaeans he was God of the Sky, di-we or di-wo, 𐀇𐀸 or 𐀇𐀺 in the Linear B script.

Crete in general and specific caves on the island came to be regarded as the birthplace of Zeus as Greek mythology developed.

An archive of clay tablets inscribed in the Linear B script used to write Mycenaean Greek was found at Knossos. Dated around 1300 BCE, they describe the worship of Diktian Zeus at Roussolakkos. That refers to a version of Zeus, one telling of the myth of Zeus, believed to have been born in the Dikte cave in eastern Crete. There are multiple candidates to be the Dikte cave, multiple ones mostly in eastern Crete and one as far west as the slopes of Mount Ida, the highest peak on Crete.

Hesiod was a contemporary of Homer. He wrote his Theogony around 730–700 BCE. In it he combined many local traditions to assemble the first Greek mythical cosmogony, or at least the first that we have today. It tells how the universe arose out of dark chaos, the genealogies of the deities, and how Zeus eventually ended up as the ruler of the cosmos.

Hesiod wrote that the Titan Rhea sheltered the infant Zeus and fed him with her goat's milk. She was hiding Zeus from his father Cronos, who intended to swallow him like his other children. Various caves and peaks have been described as the birthplace or hiding place of Zeus.

The peak was first explored by archaeologists in 1903, and then was fully excavated in the 1970s. There was a walled precinct containing a small shrine with plaster benches. It may have been oriented to align it with sunrise on the summer solstice. There was evidence of animal sacrificing and feasting.

Objects found on the peak and at this town show that there were sacred sites here throughout prehistory and into historic times. Ptolomy wrote in the 2nd century CE of a temple of Diktian Zeus that still stood at the peak above Roussolakkos.

The peak sanctuary on Petsofas has yielded a large number of clay figurines of animals and humans, like all the other Minoan peak sanctuaries. Petsofas is the only one to have included figurines of weasels, hedgehogs, and tortoises. The Minoan deity referred to as the Goddess of Animals very likely was worshiped here. Stone lamps and ceramic models of buildings have also been found there.

Some cylinder seals found on Petsofas show a male figure that seems to be the same vegetation god depicted on objects found at Knossos.

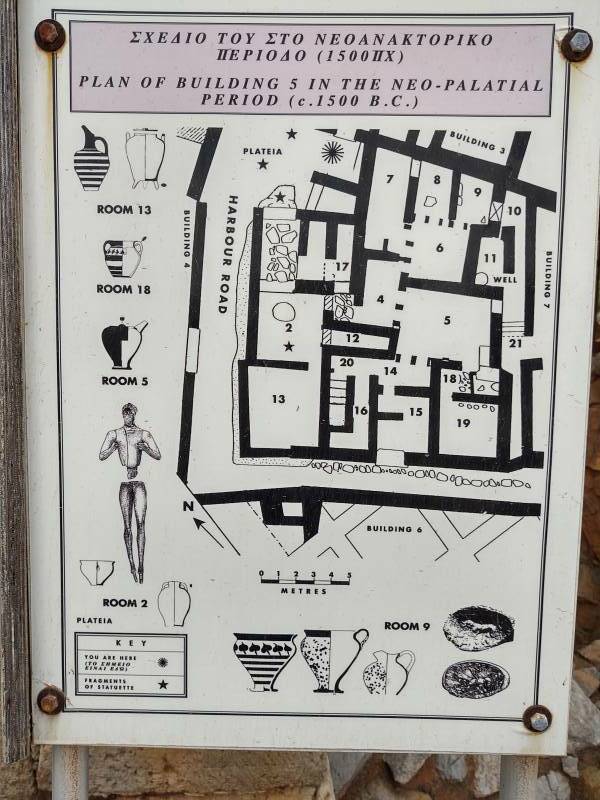

The Palaikastro Kouros was found here in various rooms of Building 5. It's a statuette of a male youth, unusually large at about 50 centimeters in height. It's chryselephantine, gold foil over ivory, specifically hippopotamus tooth. Its hair was carved from gray-green serpentine and its eyes were rock crystal. It probably represents that primary vegetation god, making it the only cult image for worship known from the Minoan civilization.

The statuette had been intentionally desecrated, burned and smashed during an ancient invasion. This probably happened around 1450 BCE when the whole city was badly burned during a Mycenaean invasion.

It was found in stages beginning with the torso in 1987, then the head in 1988, and parts of the legs about ten meters away in 1990. Thorough sieving of six tons of soil yielded hundreds of further fragments. Then four years of work were needed to assemble all the pieces. A wooden piece painted in blue pigment from Egypt and decorated with gold leaf is thought to have been its base, possibly representing the starry sky on which the god walked.

A green serpentinite boulder was very close to the kouros. It's thought that it was its baitylos or sacred stone.

Most of the cultures of the ancient Near East plus the following Greek and Roman religions had a concept of a baitylos or sacred stone. Neolithic temples on Malta and Gozo had them.

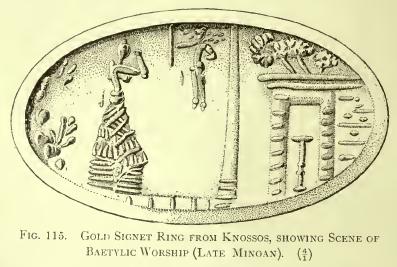

Many of the cultures recognizing these sacred stones believed that interaction with the stone could bring about a vision of a god. The Hittites worshiped sacred stones they called Huwasi stones. Several Minoan seals and large rings seem to depict someone rubbing or sleeping on a baityl.

Some of these objects were meteorites, or at least they were believed to have fallen from the sky. The one from Roussolakkos wasn't a meteorite because it's serpentinite, a mineral that contains quite a bit of water and is formed by hydration and metamorphic transformation of rock from the mantle.

Baitylos or βαίτυλος is a Greek word of Semitic origin. The Hebrew Bible contains a story of Jacob sleeping with his head on a large stone and then dreaming of a staircase reaching to heaven. Angels were going up and down the stairs and he heard the voice of God coming from its top. Jacob then named the location בֵּיח אֵל or beth-el, Hebrew for "House of God". The story was popular with European artists, who always included the sacred stone pillow.

Jacob's Ladder, Rembrandt van Rijn, 1655, etching, engraving, and drypoint, second of four states, Metropolitan Museum of New York 2012.136.464.

Jacob's Dream, William Blake, 1805, pen and ink and water color, British Museum 1949,1112.2.

The Hebrews continued to practice sleeping in sacred spots to have divinely inspired dreams or visions. In 1 Kings 3, Solomon went to Gibeon as it was the most renowned high place to offer sacrifices. He had a dream there in which he had a conversation with God, who promised he would give Solomon great discernment as a judge, plus long life if he behaved.

Some Minoan gold seal rings depict someone rubbing or sleeping on a baitylos to summon a vision of a god. In those examples the baitylos is a large oval boulder, an uncomfortable mattress rather than an uncomfortable pillow.

Sir Arthur John Evans found objects he interpreted as depicting a baitylos, although his interpretations were often his quest for evidence of what he wanted to find.

Figure 115 from Sir Arthur John Evans The Palace of Minos, Volume 1, page 160.

We see here an obilisk, in front of a hypaethral sanctuary enclosed in walls of isodomic masonry, above which rise the branches of a group of trees with triply divided leaves like those of fig-trees. Descending in front of the obelisk is what appears to be a young male God holding out the shaft of a weapon, and with his tresses flying out on either side in the manner in which motion through the air is usually indicated in Minoan art. In front of him is a taller figure, who may be identified with the Minoan Mother Goddess, with hands raised in an attitude, for which so many early Babylonian analogies exist, of prayer or incantation, and expressive of the means by which she is bringing down the warrior youth, whether her paramour or her actual son, in front of his sacred pillar. She stands on a stone terrace and behind her are rocks and vegetation indicative of a mountainous locality. Through the portal of the sanctuary itself is seen a lower pillar of dual formation set up within the enclosure, which, in view of Cypriote analogies, may be recognized as the female baetylic pillar, or at least one in which the female element preponderated.

We have here a unique illustration of the primitive baetylic cult of Crete, in which the aniconic image serves as the actual habitation of the divinity and into which, or upon or beside which, he may at any time be brought down by appropriate ritual. The obelisk in fact is literally 'God's house', as in the case of the Beth-el set up by Jacob. In a small terra-cotta shrine found in the Palace [at Knossos] belonging to the M.M. II Period we see this spiritual possession indicated by the doves perched on the capitals of the columns, or in other cases they descend on the human figure itself.

A later age seems to have regarded these baetylic pillars as actual tombs of divinities. Thus the sanctuary of Paphos was said to have contained the 'Grave' of Aphrodite and of her young male favorite, Kinyras. So, to, in the holy grove of Amathus was pointed out the tomb of Apollo, as, at Amyklae, that of his beloved Hyakinthos. In this connexion we have constantly to bear in mind the essential fact that the primitive Cretan religion must itself be regarded as an offshoot of that of a wide Anatolian region. The steatopygous images that occur already in the Cretan Neolithic strata fit on to an Oriental series, and in their later developments are to be clearly identified with a Mother Goddess whose cult, under many names and adopted by many peoples, extends far beyond the Euphrates. But, side by side with the Great Month, there also recurs throughout all this vast area a youthful satellite, variously regarded as the consort, son, or paramour of the Goddess, mortal though ever resurgent, and there is every probability the Cretan Zeus, the Child of Rhea, who represents this element in the later tradition in the island, may be traced back to its earliest religious stratum.

Evans interpreted some baitylos examples as grave markers for deities, especially the young male god who represented vegetation and went through a cyclic death and rebirth.

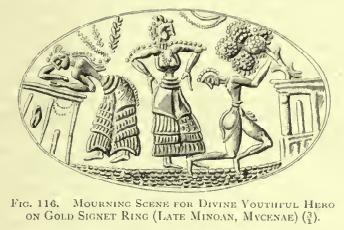

Figure 116 from Sir Arthur John Evans The Palace of Minos, Volume 1, page 161.

One of the functions of the Great Mother, the Mater dolorosa of antiquity, is to mourn her ever young but ever mortal consort, and it requires no great stretch of imagination to recognize such a scene of lamentation on another gold signet (Fig. 116). Here we see a figure of the Goddess or her attendant, bowed down, in a mourning attitude, over a kind of miniature temenos, within which stands a small baetylic pillar with a diminutive Minoan shield, seen in profile, hanging from it. To the right of this a similar figure, perhaps the Goddess repeated, is about to receive refection from the fruit of a tree, which springs from another representation of a small hypaethral sanctuary containing a similar baetylic pillar, its boughs being pulled down for her by a youthful male attendant. Here there can be little doubt that the mourning scene refers to a Minoan equivalent for Attis or Kinyras, Adonis or Thammuz, but imaged here as a youthful warrior God, in other words the Cretan Zeus.

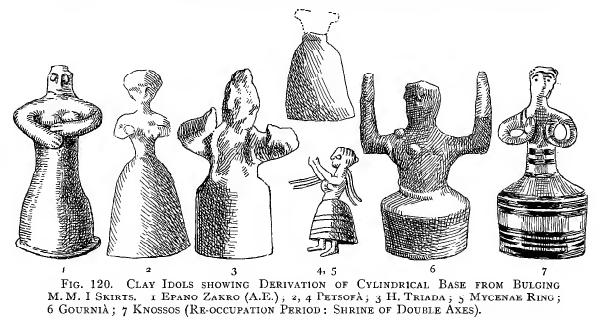

Evans interpreted the below example to depict the Mother Goddess holding her child-consort on her lap. He compares it to similar figurines found at the peak sanctuary up on Petsofas, above Roussolakkos. He then speculates as to whether its base is a bell-shape skirt, or if it instead is a baitylos.

Figure 327 from Sir Arthur John Evans The Palace of Minos, Volume 3, page 469.

Figure 120 from Sir Arthur John Evans The Palace of Minos, Volume 4, Part 1, page 162.

The baitylos was believed to be sacred because of something inherent to its nature. Human intervention such as carving wasn't necessary. However, sculptors worked on some of them, changing their overall shapes to more of a cone or cylinder, or inscribing writing.

The 10-volume

Dictionnaire des Antiquités

Grecques et Romaines,

published in 1873-1919, has a six-page entry

for baetylia,

which is the word for several of them.

Pg 642

Pg 643

Pg 644

Pg 645

Pg 646

Pg 647

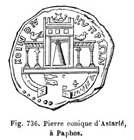

Conical stone of Astarte, at Paphos fig 736 pg 642.

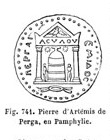

Stone of Artemis of Perga, in Pamphylia, fig 741 pg 645.

Carved baitylos, fig 743 pg 646.

Kos

The ancient Greeks used a practice they called έγκοίμησις or incubation, sleeping in a sacred area in the hopes of experiencing a divinely inspired dream, or being cured of some malady. This was one of many practices at the ancient Greek medical school and treatment center at Asclepios on Kos, where Hippocrates taught and practiced medicine.

VisitingDelphi

The ancient Greeks believed that Delphi was the center of the world, marked by Zeus with the όμφαλός or Omphalos, a special navel-of-the-world stone. The Omphalos seems to have been a nominal concept, modified and recreated over time. A specific Omphalos is in the museum today, matching some but not all of the ancient descriptions. A simpler but adequately authoritative version marks the spot where the museum's stone was found.

The Omphalos, the Center of the World, in Delphi.

The "real Omphalos" in Delphi back then, sort of like the "Real Original Ray's Pizza" as opposed to the "Genuine Original Ray's Pizza" and other competing variants in New York City, was anointed with oil every day and draped with raw wool on special occasions.

The Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I shut down oracular activity in 395 AD and soon Delphi was largely destroyed, further confusing matters for today's archaeology. That led to a Christian Omphalos being set up in Jerusalem, based on the medieval European cosmology of Jerusalem being the spiritual and physical center of the world. That was in turn based on an earlier Jewish cosmology calling Jerusalem the Navel of the World.

The Jewish tradition doesn't date back to the exodus out of Egypt. It began in Hellenistic times, when Greek culture was well established throughout the Levant. The Jewish people were very familiar with (and largely immersed within) Greek culture, and the Jewish tradition might have come directly from the Greek one about Delphi.

The Ark of the Covenant was kept in the Ark of the Temple in Jerusalem, where it rested on the Foundation Stone, the אֶבֶן הַֺשְתִײָה or 'Even haShǝṯīyyā marking the "navel of the world". This was the holiest location in Judaism, and Jewish prayer is performed facing toward the Foundation Stone. Going further back into tradition, this was the threshing floor that David purchased and offered sacrifices upon, and before that, the stone where Abraham almost sacrificed Isaac, and before that, the stone upon which Noah, Cain, Abel, and even Adam himself offered sacrifices.

Theodosius I was shutting down oracular activity in the 390s when the Christian theologian Augustine of Hippo was active. Augustine and other ecclesiastical writers denounced the baitylos worship that was still going on in former Phoenician colonies including Tyre, Sidon, and Carthage.

The Temple Mount in Jerusalem is now topped by the Islamic shrine built in 689-691 CE, Masjid Qubbat As-Sakhrah or Dome of the Rock, also known as the Bait-ul-Muqaddas or the Noble Sanctuary. It was built around the exposed Foundation Stone, which Muslims also believe was the keeping place of the Ark of the Covenant. And, more significantly to them, the location where the angel Gabriel took Muhammad to pray with Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, and where Gabriel took Muhammad to heaven.

The baitylos practice survives today with the Black Stone embedded in the east corner of the Kaaba in Mecca. Islamic tradition holds that the Black Stone fell from heaven to guide Adam and Eve to build an altar, and then in 605 CE the prophet Muhammad set it into the wall of the Kaaba. And, that the Kaaba was originally built by Abraham and Ishmael to use their Hebrew-in-English names, or Ibrahim and his son Ismail for Hebrew-in-Arabic-in-English. Some time before the origin of Islam, the Kaaba became a holy shrine to which the Bedouin tribes would make a pilgrimage once a year to worship their wide variety of gods.

The Black Stone was part of that pre-Islamic shrine, and it was all in one piece at the time. It was broken into several pieces in 683 when the Umayyad Caliphate was besieging Mecca with catapults, then fastened together with a silver ligament. Since then the pieces have been broken apart, rearranged, and cemented back together multiple times. The current appearance is of seven or eight major pieces, each made up of several small fragments.

AbbasidCaliphate

In 930 CE the Qarmatians stole it and took it to their base in Hajar, hoping to steal the hajj business away from Mecca. That failed, as the pilgrims kept going to its previous site. The Qarmatians demanded a huge ransom, which the Abbasids paid in 952. That caper further broke up the stone, what with the removal and theft, and rough treatment during the return.

Reassembled and cemented back together multiple times and now surrounded by a silver frame, it's at the core of the pilgrimage ritual. A pilgrim is supposed to kiss the stone, or at least touch it if they can't kiss it, or at least point at it if the Kaaba is too swarmed with pilgrims to touch it.

All scientific investigation is kept far away, so no one really knows what the Black Stone is. However, geologists doubt that it's really a meteorite.

Back to Roussolakkos...

A fence surrounds the site. Reburied excavations extend a significant distance onward toward the shoreline.

Much research remains to be done. Potsherds litter this area of the ruins.

Someone has gathered these, putting some on large foundation stones.

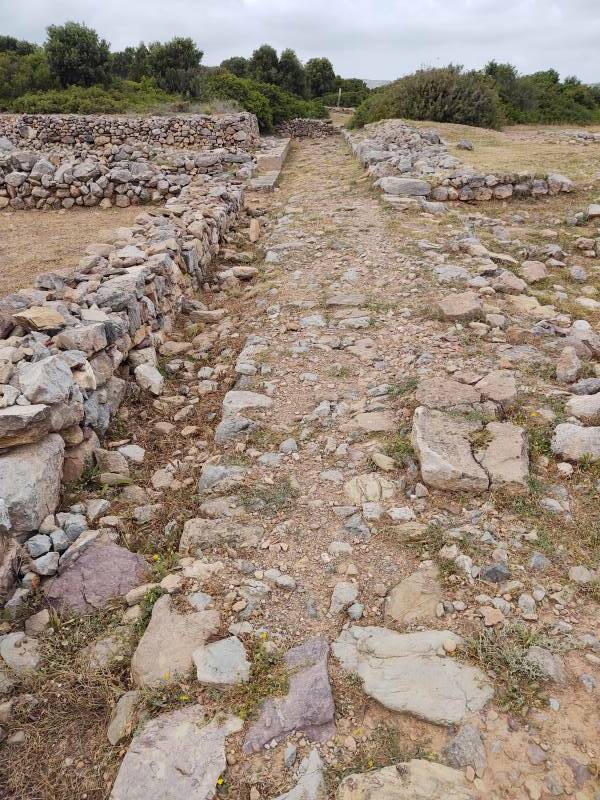

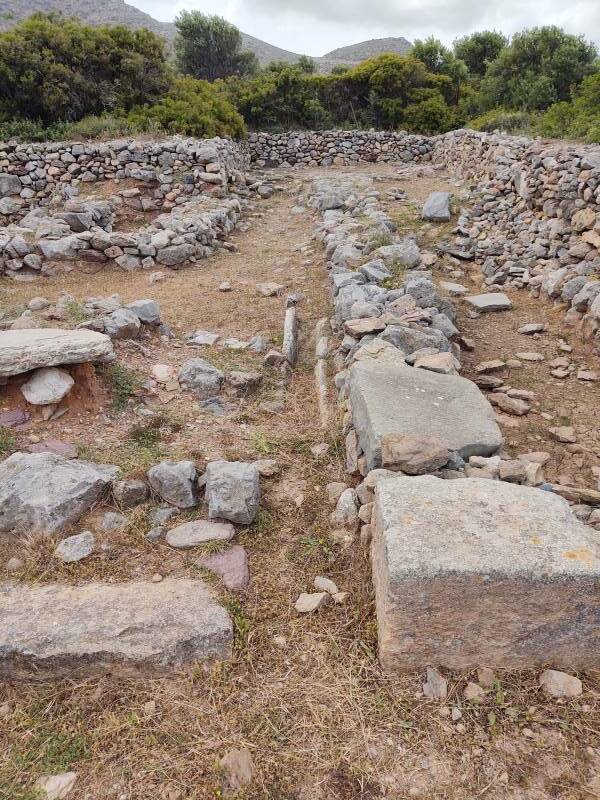

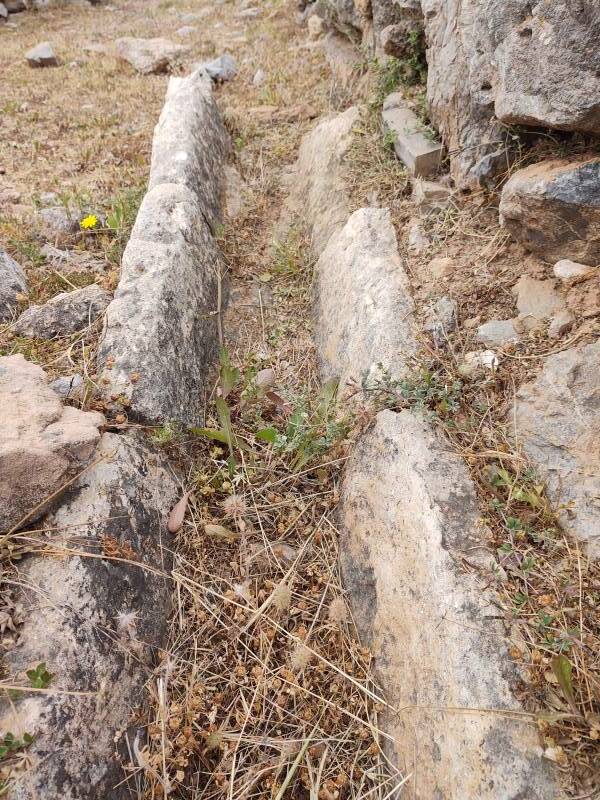

This main road and the roads perpendicular to it divided the city into nine districts. A drain runs along the left side of the road in this view.

Plumbing

Like other Minoan sites I visited at Knossos, Malia, Phaistos, and Agia Triada, the Minoans had separated drain systems, isolated storm drains and waste or sewage drains. Many cities in the U.S. still don't have this sanitary technology.

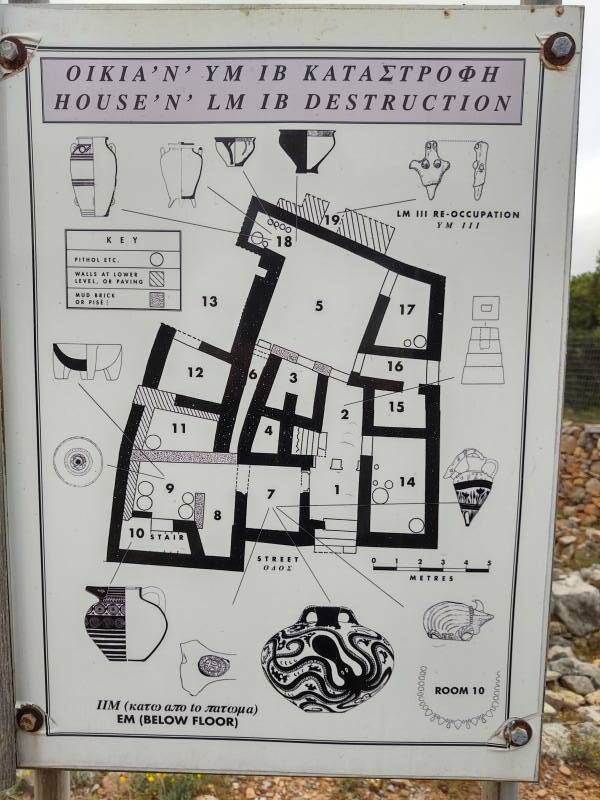

House N contained a shrine with Horns of Consecration and stands for double axes in an upper room. See the page about Knossos for details on those Minoan symbolic objects.

Or, Continue Through Greece:

Where next?