Agia Triada

The Minoan Settlement at Agia Triada / Αγία Τριάδα

Agia Triada or

Αγία

Τριάδα

is a Bronze Age site in south central Crete,

between the Libyan Sea coast and the Minoan palace complex of

Phaistos.

Agia Triada was not a Minoan palace like Phaistos,

Knossos,

or Malia.

It was a sophisticated town with two large residences,

possibly a royal villa and a second large mansion.

It also had a supporting settlement of craftsmen,

laborers, and other staff.

It seems to have been the administrative center

for the port of Phaistos.

The Mycenaean Greeks attacked Crete around 1450 BCE.

They destroyed Phaistos and other major Minoan palace complexes.

Agia Triada was rebuilt after the Mycenaean attack

and took over the role as capital of south-central Crete,

continuing until the 13th century BCE.

You'll need a car to get to Agia Triada.

It's over the central ridge from Heraklion,

near the south coast of Crete.

The Roads company makes excellent maps of Greece,

buy a map at a service station.

Θα

ήθελα

έναν

χάρτη,

παρακαλώ —

I would like a map, please.

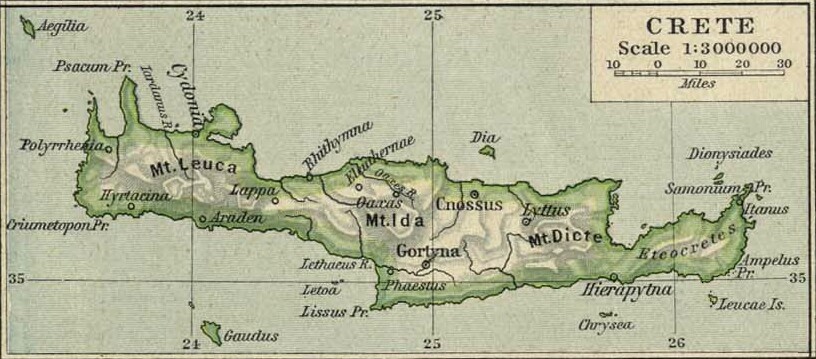

Don't rely entirely upon this 1926 map of Ancient Greece,

although it does orient you to where Agia Triada

is located within Crete.

See Phaestus, also spelled Phaistos,

west of Gortyna and near the southern coast.

Agia Triada is between the coast and Phaistos.

Heraklion is now the largest city in Crete,

but it was just a small port town

during the ancient period depicted on this map.

It's on the coast north of Knossos, shown here as "Cnossus".

Gortyna was the capital of Crete until Arab traders

from al-Andalus, today's Spain, founded the Emirate of Crete

in the 820s and moved the capital to today's Heraklion.

1926 map of Ancient Greece from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. "Hey, you know what would be a great way to write Greek words within English text? Write them in Latin with weird ligatures like 'Æ', the way the Romans did! Then anyone who has studied how the Romans wrote and pronounced Greek would be comfortable!" For those of us who didn't go to an English boys' boarding school with the associated rum, sodomy, and the lash, the pointless Latin spelling is silly and a bother.

This map shows the topography of the area. Agia Triada and Phaistos are in the broad valley of the Messara plain. They're on a small ridge between the coast and Moires or Μοίρες, labeled as Moírai on this map. To the north is the Psiloritis massif including Mount Ida, the highest peak in Crete at 2,456 meters or 8,058 feet. To the south of that valley is the Asterousa mountain range running parallel to the coast.

The broad valley is an alluvial deposit, rich agricultural land inhabited since the Neolithic. In the Early Bronze Age settlements began forming along the lower slopes of the Asterousa range, along the south edge of the valley.

Tactical Pilotage Chart G-3D from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

And finally, when you get close and need turn-by-turn directions:

So What is the Name of the Place?

It's in Greece, so the name is: Η Αγία Τριάδα. Yes, that means "Holy Trinity", a very anachronistic name! After the settlement had been abandoned and largely forgotten, the small church Εκκλησία Αγία Τριάδα or Ekklesia Ayia Triada happened to be built only about 280 meters to the southwest. A village grew up around the church. You can still visit the church, although the village has disappeared. When the ancient site was re-discovered, the area was already named for the church and former village.

As for representing the name in the Latin script for English speakers, the Greek Αγία or ΑΓΙΑ may be rendered literally as "Agia", phonetically as "Ayia", or traditionally as "Aghia", "Hagia", or "Haghia". Who knows what you will find in any given map or book. Ayia is the one that an English speaker will pronounce closest to how a Greek speaker says it. The traditional spellings would be familiar to attendees of British boys' schools before the middle of the 20th century, where they studied Ancient Greek and New Testament Greek and ignored the language spoken by actual living Greek people. The extra H's have to do with "rough breathing", something that had disappeared from spoken Greek well over 2,000 years ago.

The Christian New Testament was written in Koine Greek, which preserved what even then were archaic features no longer used — rough versus smooth breathing and a pitch accent system. Unfortunately, starting in the 19th century when the Ottoman Empire still controlled much of today's Greece, there was a movement to change the language to a blend of Ancient Greek and the modern form. All government and legal documents were written in this katheravousa. Highly educated people could read it with a significant struggle, but most people couldn't. Katheravousa wasn't completely abolished until a spelling reform in 1982. Now we need to reform how Greek words are spelled in English. The fact that modern Greek people speak and spell things in a modern way gets largely overlooked outside of Greece.

Arriving at Agia Triada

Beware, online maps will direct you to a service entrance below the site. Use Google Maps to get in the general area, but follow the road signs in the physical world. The official entrance is off a somewhat rough gravel road that climbs the ridge above the site and continues on to Phaistos. You park at the large sign along that road and walk down a series of staircases to enter the east side of the complex.

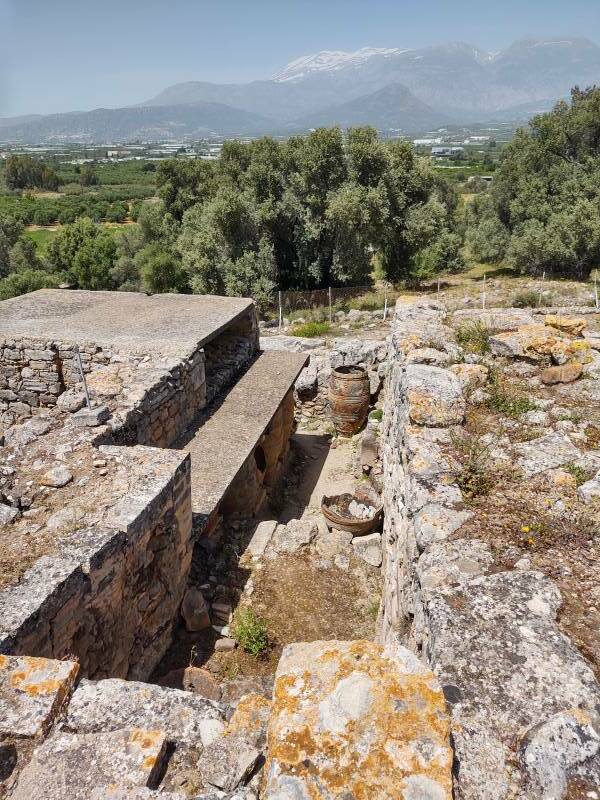

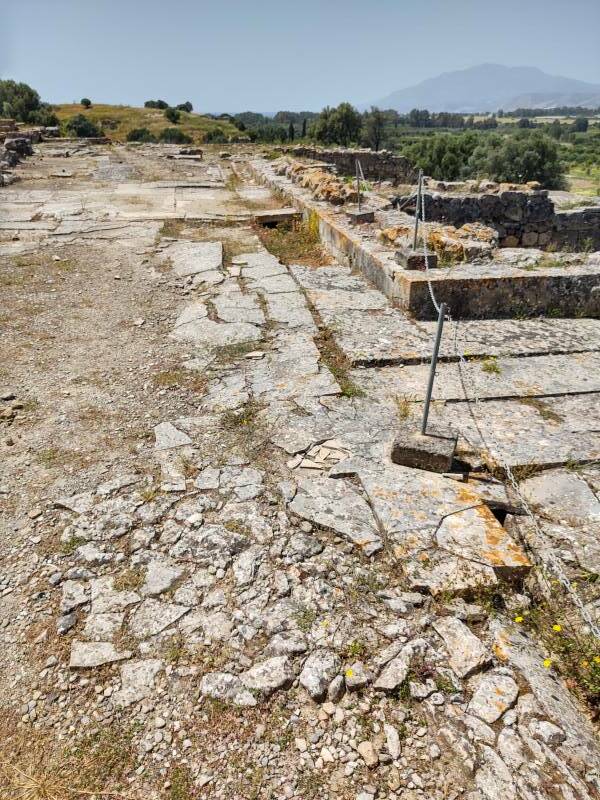

Agia Triada is an L or Γ-shaped complex. As you enter you're looking over the better preserved of the two large structures, protected by a modern roof, and beyond that to the coast and the Libyan Sea.

The Italian Archaeological School of Athens excavated here and at nearby Phaistos from 1900 to 1908 and again from 1910 to 1914. While study continues today, the majority of the excavations were completed by the start of World War I in 1914. However, that early work was only published in the 1980s!

To the right of the entrance is the support town, a cluster of small houses and an agora, an open market area. A στοά or stoa, a line of workshops and/or stores, lines the uphill side of the small agora like an ancient strip mall. Objects found in this area show that the homes were occupied by craftsmen and farmers.

These pictures are from a visit in late April. Snow still remained on Mount Ida and the Psiloritis massif to the north, even on the south-facing slopes.

Ϝ Yes, archaic Greek had a /w/ letter, Ϝ/ϝ or Digamma. Mycenaean Greek had a /w/ sound, but it had disappeared from most Greek dialects before the Classical period, so before about 500 BCE.

We're looking toward the agora over the ruins of a temple to Welchanos or Ϝελχάνος, a Minoan vegetation deity.

Sir Arthur John Evans excavated Knossos from 1900 to 1936 and has had a huge influence over everyone's understanding of the Minoan civilization. Evans said that a tree cult was one of the most important components of the ancient Minoan religion. There was a pair of deities, one female and one male with a mother-and-child relationship who were also in a hieros gamos or ίερός γάμος, a "holy marriage". That sounds weird, but the idea was very Mesopotamian. The Mother Goddess, the more powerful of the two, was a personification of tree vegetation. The young male god or κούρος formed a "concrete image of the vegetation itself in the shape of a divine child or youth".

Arthur Evans and his assumptions, rash conclusions, and inventionsHowever... Much of what Evans "discovered" were based on his idealized dreams of what could or should have been. He forced what he found into what he wanted to have found. Evans's visions, inventions, and forgeries became the official description of Knossos and the Minoan civilization. The deciphering of Linear B in 1952 led to broad questioning of some of his conclusions, and much more was debunked in the following decades.

What we can be confident about is that Welchanos was associated with vegetation and fertility, and thus with the seasonal cycle of death and rebirth. When the Mycenaean Greeks arrived, they identified Welchanos as their own supreme deity. This was a precursor to Zeus, although they didn't call him by that name. To the Mycenaeans he was God of the Sky, di-we or di-wo, 𐀇𐀸 or 𐀇𐀺 in the Linear B script.

What Happened Here?

This support settlement at Agia Triada was established before the large mansions, and then grew once the overall complex became more established.

Researchers have found copper ingots here, showing that there were metal-working workshops. The ingots were probably imported from Cyprus. Copper could be used for drinking vessels, decorative items, jewelry, and similar, but it wasn't strong enough for tools or weapons. But if you mix in about 12–12.5% tin, you get bronze. As in the Bronze Age, the period in which bronze was the hardest metal available. The tin probably came from mines in the mountains of what is Afghanistan today.

We don't really know very much about the Minoan civilization. They left very little in the way of written records. We don't know how to read what little we have found, beyond a few inventory lists of food storage and offerings made to deities we know little about.

This is why we call the site "Agia Triada", naming it after a nearby small village built 2,000 years later. We have no idea what the inhabitants called the place. We don't know what they called themselves. "Minoan" is a name used by Sir Arthur John Evans, who had immediately concluded that of course Knossos must be the palace of King Minos of myth.

The Minoan civilization was sophisticated but literally pre-historic. They wrote nothing about their history, myths, or current events.

Agia Triada is usually described as the "summer palace" of the rulers of Phaistos, three kilometers to its east. It very likely served as the administrative port town for Phaistos, although the harbor would have been another three kilometers to the west.

Evans began applying the term "palace" almost immediately upon beginning excavations at Knossos in 1900. Yes, Knossos seems to have been an administrative center. But applying the term "palace" to every large complex tells us nothing about whether they were controlling centers of small empires, or simply prominent settlements within a commonwealth of autonomous local principalities.

Pithoi

The plural is πίθοι, usually spelled in Latin script as pithoi. Given vowel shifts through the millennia, Greek –οι is pronounced like "ee" in English feet, so it's pronounced as if it were pithy.

A πίθος or pithos is a large storage container made of fired clay. Pithoi stored grain, oil, and other bulk goods.

A full pithos would be enormously heavy! They were made with multiple handles or rope attachment points so a small crane could move them.

Eastern Villa

Here is Agia Triada's slightly larger residence under the modern roof. The staircases show that this structure had at least two floors, of which only the lowest survives. Notice the open plaza to its west, between the two villas, in the distance at upper left here.

A large drain runs to the left of that staircase. It carried rain water from the open plaza.

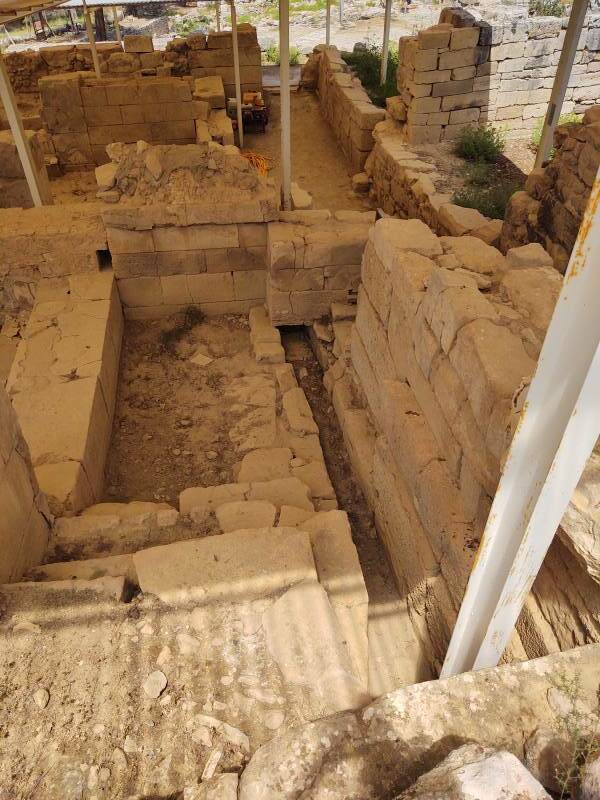

Below the floor of the villa, the drain line turns 90° toward the north and another drain line joins it.

Another drain line runs at a higher level. It is built from stone channels with U-shaped cross-sections.

Plumbing

The Minoans are renowned for their water management technology. Storm water drains like these, with separate sewage drain systems. Plus clean water supply lines.

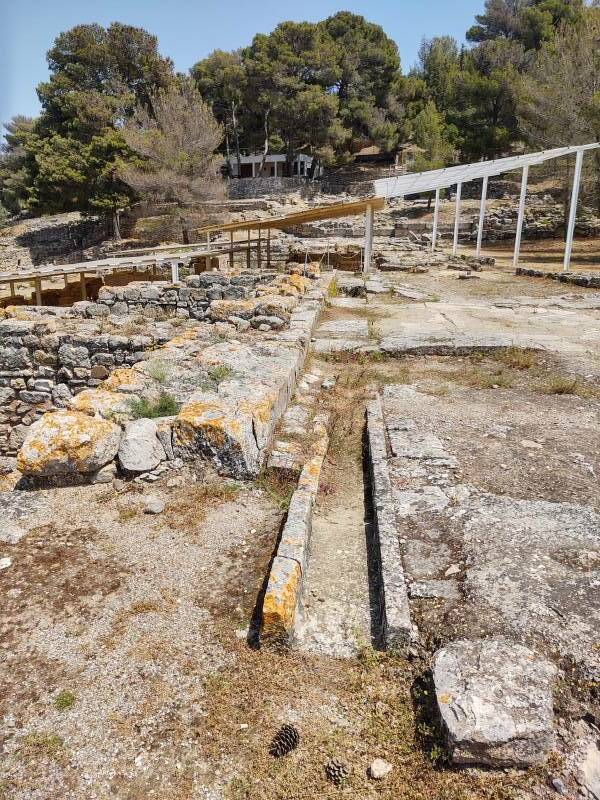

Out on that plaza we see where the water was collected and sent into the storm drain system. While this was a significant plaza, it wasn't a central courtyard fully surrounded by sizable structures, as found at what we consider to be true palaces at Phaistos, Knossos, and Malia.

Western Villa

Continuing to the west, and then turning to look back, we can see ruins of the western villa. Beyond it is the eastern villa under the modern roof, and the agora and stoa of the workers' town to the left.

Workers' quarters are at the far southwest corner of the site.

The small church of Saint George stands above the site. It was built during the 1300s when the Venetians ruled Crete.

The Lustral Basin

The west edge of the Agia Triada complex contains a lustral basin. This rather fanciful term was born from Sir Arthur John Evans's wishful thinking. They almost certainly were not used for "lustration" or ritual bathing as he claimed. But, since the Minoans seem to have recorded almost none of their religious or cultural practices, we don't know what they were used for. These so-called lustral basins are found with a consistent design at many Minoan sites, so there must have been some standardized purpose for them.

A lustral basin is within what's called "the Room With Benches" in the western villa. Let's take a look at it.

Sure enough, the room is lined with benches along its three walls. The lustral basin is to the left as you enter.

Here it is! This is a rare opportunity. You can't get close enough to the lustral basins at Knossos, Phaistos, and Malia to see into them, let alone step right in. But, there's not much to see here.

This one is a little different. Most of the lustral basins were approached by a short staircase that made one or two 90° turns that entered the basin at one corner. However, you simply step right into this one.

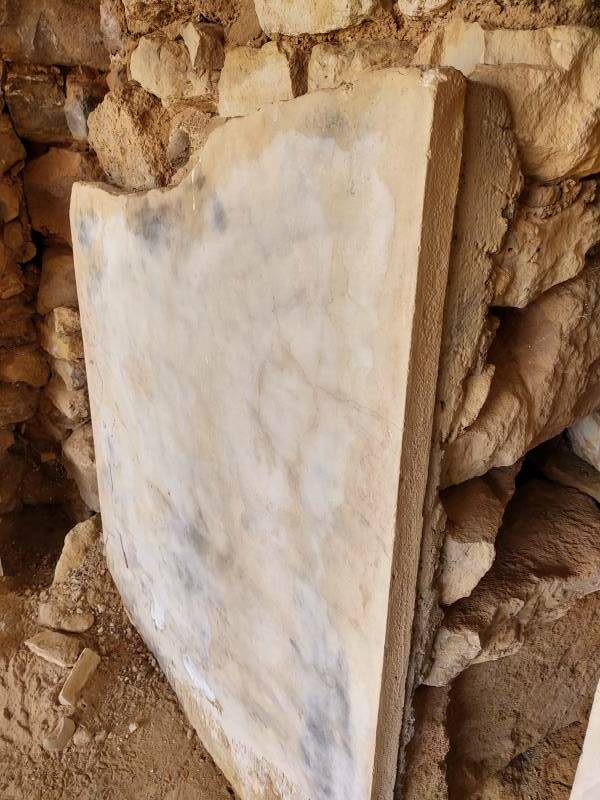

One reason we're pretty certain that the lustral basins weren't used for ritual bathing, that they couldn't be used for ritual bathing, is that they were lined with panels of gypsum.

Gypsum is a soft and moderately water-soluble mineral, CaSO4·2H2O. Lining a ritual bathing chamber with gypsum would be like lining your bathtub with bare sheetrock or drywall, or plaster, or chalk, which are all made from gypsum.

Plus, while the Minoans clearly understood both drains and water supply lines, none of the lustral basins found so far have any associated plumbing.

So, there must have been some standard ritual use. But we don't know what it is. Other than it wasn't bathing.

Above and below are some further large gypsum panels in the room with the benches and the lustral basin.

The Agia Triada Sarcophagus

One of the outstanding finds at Agia Triada is a large limestone sarcophagus. It dates to just before the Mycenaean invasion, 1400 BCE or shortly thereafter.

The sarcophagus is interesting because of how it's different from most such objects.

A λάρναξ or larnax is a small coffin, bone-box, or ash-box used for human remains. And so the plural is λάρνακες or larnakes. Here are several larnakes in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

One of them is decorated with an octopus theme, a common style of larnax.

However, Minoan larnakes usually have drain holes. See the drain hole at the end of this one. So, it seems that their owners may have used them as bathtubs before being buried in their tub.

The Agia Triada is totally different. It's carved from limestone instead of being shaped from ceramic material and fired. It's of a flat-sided rectangular shape instead of being curved like a bathtub. It's coated with plaster and painted with frescoes on all its surfaces. And finally, it has no drain, it could not have been a bathtub.

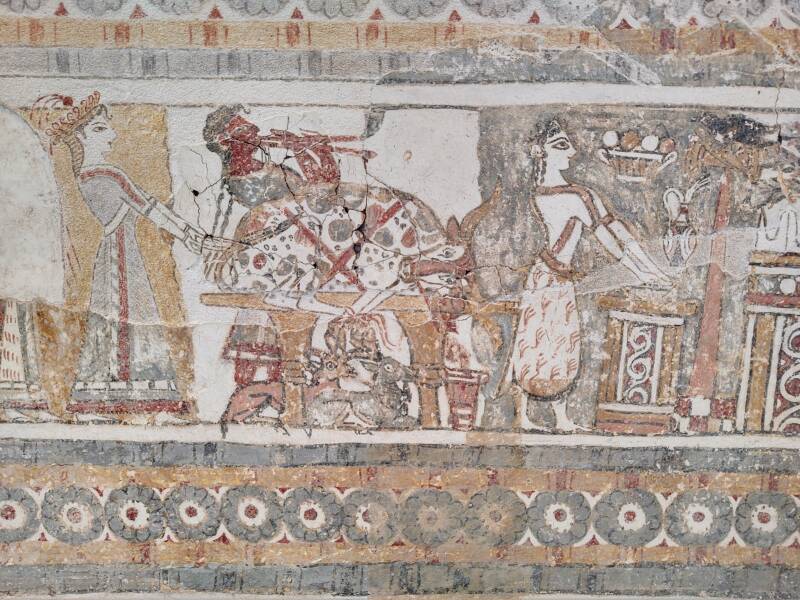

As far as we have found, other than this object, the Minoans only used frescoes to decorate palaces and homes. This is a unique piece. Also, it depicts scenes of Minoan funerary rituals. We have no written descriptions, but at least there are these pictures. Historians think that these probably combine Minoan and Mycenaean rituals and artistic styles, influenced somewhat by Ancient Egyptian religion.

This side show a bull tied down on an altar and being sacrificed. Its blood is pouring into a conical rhyton or other ritual container. Small animals, or possibly terracotta models, are under the altar table. They might be calves, goats, or deer. A man standing behind the altar is playing an aulos, a double flute. As usual around the eastern Mediterranean, women are depicted with much lighter skin than men, white rather than brown to dark red.

A woman to the right of the central altar faces a pole with a labrys or double ax at its top, with a black bird sitting on it. At the far right (fully visible above, partially below), there is either another altar or the tomb, topped with four Horns of Consecration symbols, and with a seven-branched tree in the background. Welchanos the Minoan vegetation deity? Maybe.

The low altar at the center would probably be for the chthonioi or earth deities, and the high altar at the right for the ouranioi or sky deities.

On the opposite side of the sarcophagus, starting at the left, a woman is pouring liquid into a large bronze cauldron. This might be the bull's blood collected in the scene on the opposite side. The cauldron sits between more poles topped with labrys or double axes.

Behind her is another woman carrying a pair of vessels on a yoke. Maybe it's more blood. You can get a lot of blood out of a bull. Forty liters or more.

Behind her is a man playing a seven-string lyre. This is the earliest known depiction of a Greek-style lyre. Although, since this dates from before the Mycenaean Greeks arrived on Crete, what we think of as a "Greek lyre" is actually a Minoan instrument.

To the right are men carrying models of animals and a boat toward a man shown who is depicted without arms or feet. Scholars believe that he is the dead man, receiving animals and a boat for his journey to the next world.

Largely self-taught philologist Michael Ventris decoded Linear B in 1952. He found that it recorded an earlier form of Greek. It was what the Mycenaeans spoke.

Once we knew how to read Mycenaean Greek, scientists found that some Linear B tablets describe rituals that correspond to what the sarcophagus shows.

The Minoans used the earlier Linear A script to make records in their language, or languages. That's right — we not only don't know anything about the language that they spoke, we don't even know if it was a single language or maybe multiple ones.

How do we know that Linear A is older than Linear B? Stratigraphy, the science of figuring out ages, or at least relative ages, based on the layers at which objects are found. You have to limit the analysis to objects found in undisturbed layers. Pottery of distinctive styles, trade items, and other objects found within the same layers can tie ages together within one site or between multiple sites even at great distances.

More Linear A tablets have been found at Agia Triada than at any other Minoan site. Here's what it looks like, these Linear A tablets are in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

Linear A tablets in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

All the Linear A text that we have found adds up to 1,427 specimens containing a total of 7,362 to 7,396 signs, depending on how you interpret some partially damaged pieces. Printed in a standard sized font (and there is a Unicode definition for the Linear A script), the entire Linear A corpus would easily fit onto two sheets of paper.

Linear A tablets in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

As far as researchers can figure out, the Linear A samples we have are mostly inventory records of trade goods, offerings made to various deities, and labels on pithoi indicating what they contain or who owns them.

The relatively large volume of Linear A records indicates that Agia Triada handled a lot of goods. It probably was the headquarters for the nearby port run by the palace at Phaistos. Many of the non-elite inhabitants who weren't craftsmen were probably much like the administrative and scribal workers in Egypt at that time. They maintained records of sales and purchases, transfers of goods, and shipping.

Linear A tablets in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

The Linear B script was derived from Linear A. Some signs are identical or nearly so. Others are clearly derived from similar Linear A signs. Still others are completely different, mystery signs.

Linear B was used to write Mycenaean Greek, and we have a pretty good idea of how pronounce that early form of Greek. And so...

The obvious experiment is to select some Linear A tablets containing just those signs with clear mappings to Linear B signs that we know how to pronounce. Then, read those Linear A tablets phonetically to experts in the various languages spoken in the lands around the eastern Mediterranean in the second millennium BCE.

The experts don't recognize anything. They don't even notice slight similarities to known languages.

Linear A tablets in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

So, to really make your mark in Bronze Age studies, figure out how to read Linear A. Or, figure out how a "lustral basin" was really used. Good luck!

Or, Continue Through Greece:

Where next?

The leading "H" in the names Homer, Herakles, Hera, Hades, and so on, were pronounced way back when because there was a "rough breathing mark" on the intial vowels of those names. But rough breathing is nowhere to be seen or heard in modern Greek.