Rizinia / Ριζηνία

Rizinia and the Siderospilia Necropolis

This page moves up into central Crete,

from the Messara valley over the central ridge

toward Heraklion on the north coast.

The road runs along the east side of the Psiloritis massif.

There aren't many places to run a road through there.

Today's highway follows the path of a road going back to

Minoan times.

A Minoan town named Rizinia

had an akropolis, a high settlement on a peak

overlooking and controlling the north-south road

joining the two coasts.

There's a nice small church up there,

an active structure on a peak otherwise

quiet since the Hellenistic Period of 323–31 BCE

and before that to the Greek Dark Ages of 1100–750 BCE,

with connections to the even earlier Minoan periods of the

millennium before that.

Tactical Pilotage Chart G-3D from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

The Roads company makes excellent maps of Greece. Buy a current map at a service station. Θα ήθελα έναν χάρτη, παρακαλώ — I would like a map, please.

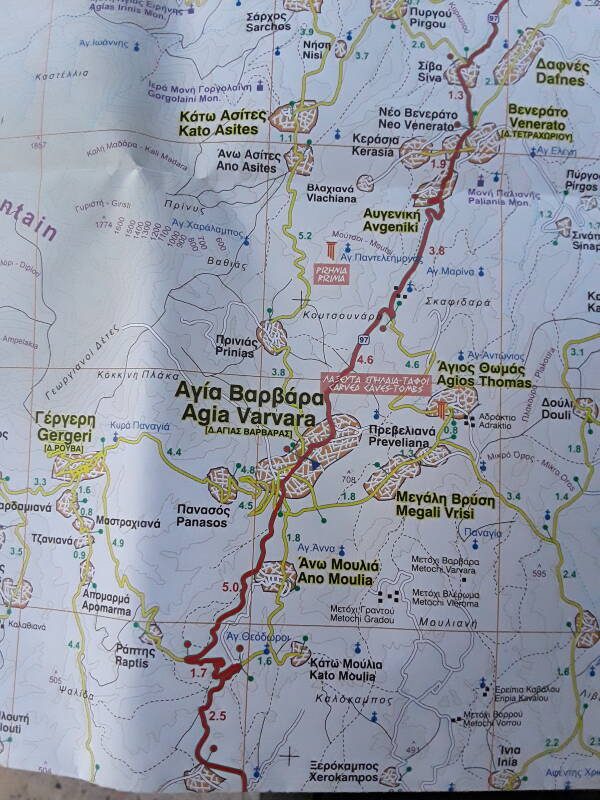

This trip takes us off on a small lane off a side road. The Roads maps have good markings of archaeological sites.

Paper maps are the best for visualizing the entire route, and spotting interesting things along the way. I'll look at my map while having breakfast in Heraklion. Koulouri or sesame bread, very similar to the simit of Turkey, and a double Greek coffee.

Now I'm caffeinated, it's time to get on the road.

Through Central Crete

Any route that you take through central Crete will have great scenery. The new highway, which I think opened around 2019, makes for easy driving. But at least once, take the old road that goes through Agia Varvara and Ano Moulia, through the villages and through many twists and turns with steep drop-offs and few guardrails. Here's a view to the southeast, into the upper end of the Messara valley.

This view is to the southwest, with the Psiloritis massif at right descending toward the Libyan Sea coast off the left side of the picture.

Looking west at the Psiloritis massif, we're looking toward Mount Ida. At 2,456 meters or 8,058 feet, it's the highest point in Crete.

There are also sudden drop-offs within the villages. Either do or do not go down the alley to the left. Pick a direction, don't leave your car hung up in the middle.

There are minimal guardrails, so make sure not to go off the side of the road.

To Rizinia

The village of Prinias is about 3.5 kilometers north of Agia Varvara, across the new highway. Prinias is built on the site of ancient Rizinia, of which very little remains.

The patela or "naked expanse" of Prinias, a flat-topped mountain a short distance north, was the mountaintop akropolis of ancient Rizinia. That fortified outpost allowed the people of Rizinia to observe and control traffic on the road between the north and south coasts. Today's main highway follows the ancient road because it's the only practical route linking the coasts.

Go to Prinias and continue through it toward the northwest on a two-lane road. You'll see a yellow-on-brown sign indicating an archaeological site, and from there a gravel lane leads to an area where you can park.

There's my rental car. I've started up the path. Heraklion and the Aegean Sea are visible in the distance.

The flat peak is about 200 meters north-south by 500 meters east-west, tapered toward each end. It's at an elevation of about 700 meters, putting it about 300 meters above the highway. The north and south slopes would be impractical approaches, the east slope even more so. The steep lane approaching from the road to the west, followed by some walking, is the easy way to get there.

I'm on the path along the north edge of the peak, headed toward the chapel at the northeast corner.

Turning to look back, I see the Psiloritis massif looming above everything.

A strong wind called the meltemi or μελτέμι blows north to south through the Aegean from May through October.

Grass, bushes, and trees on an exposed peak like this grow curved under the constant wind.

Ekklisia Agios Panteleimonas

The chapel is out at the northeastern tip of the mountain.

Compared to the terrain I'm used to, this is pretty high and isolated. But if we were really up on a peak, the church would almost certainly be dedicated to Agios Ilias, the Prophet Elijah in English, associated with mountain peaks.

Churches are often locked, but this one was open. Possibly because it's off on its own, far from any houses, and it could serve as a shelter from the wind.

I stepped in. There was a ventilated smoke hood for candles to your left as you step in, at the rear of the small nave.

A lectern stood between the door and the smoke hood. During a service the lectern would hold liturgical books containing the Orthodox service written in Byzantine Greek. The New Testament, however, is read in the Koine Greek that it was written in almost two millennia ago.

A standard iconostasis filled the front of the nave. Mary holding and gesturing to Jesus at the left of the central door, and a Pantokrator "All-Ruler" image of Jesus to its right. The point is that the first and second comings of Jesus flank the central door leading to the altar.

A door for a priest or deacon to access the altar area is at the far left, and the person to whom the church is dedicated is depicted at the far right. There's also a series of smaller New Testament images across the top — typically including the Annunciation, the Nativity, Jesus's baptism by John, the raising of Lazarus, the Μεταμόρφωσις or Metamorphosis or Transfiguration, the Crucifixion, the ανάσταση or Anastasis or Resurrection, Πενηκοστή or Pentacost, and a few more.

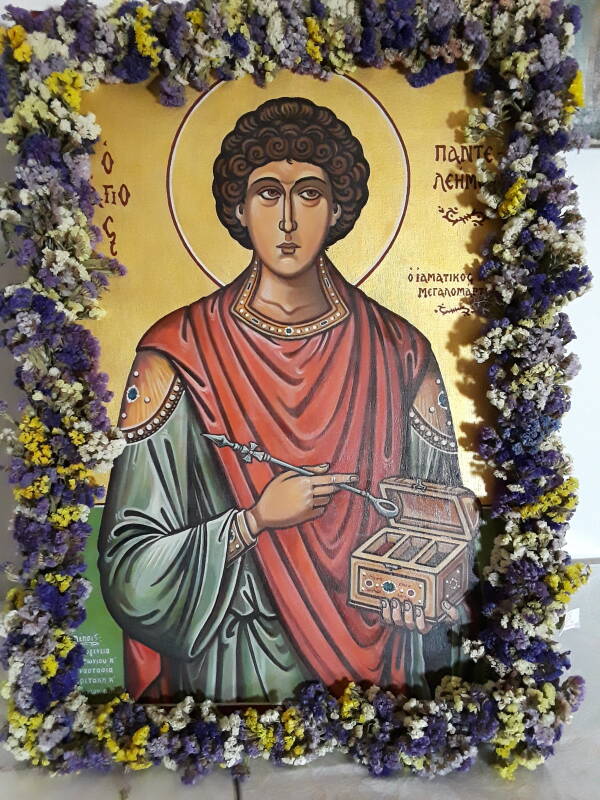

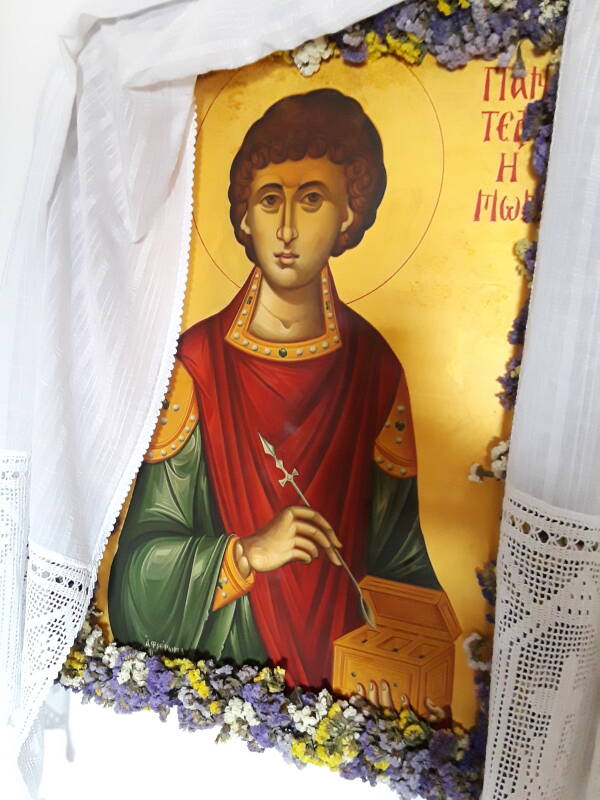

There were several icons of the patron saint on the left wall.

Let's see who this is.

Ο Άγιος Παντελεήμων.

Saint Panteleimon. What is he holding?

Saints are frequently pictured with the weapon or tool or other device with which they were martyred. Catherine with a spiked wheel that was set on fire. Swords. Axes. Cauldrons of boiling oil or molten lead. Several are pictured with saws, as their legend tells that they were sawed in half in various planes — sagittal, coronal, or transverse.

Hippocrateson Kos

Panteleimon was trained as a physician, so he might have sawed a few fetal pigs along various planes during his pre-med schooling. But probably not. It wasn't the 20th century CE.

He's associated with and is holding a lancet in the standard, literally iconic, representation. He wasn't martyred with a lancet, it's a tool he used.

If you had a boil or abscess, Panteleimon could lance it.

Constantinople

Panteleimon was from Nicomedia, near Constantinople at the east end of the Marmara Sea. He was born in 275 CE, and then martyred during Diocletian's persecution in 305.

There are various stories of his performing miraculous healings of the blind, the paralyzed, and the snake-bit. And, as is common in martyrologies, there are many wild tales of failed attempts to kill him. He was to be burned with torches, but the torches were extinguished when they touched him. A cauldron of molten lead was prepared, but the fire went out and the lead solidified and became cold. He was tied to a huge stone and thrown into the sea, but the stone floated. He was thrown to wild beasts, but they went all Disney to frolic around him and lick his feet. They tried to behead him, but the sword just bent or, in some versions, melted like wax in a flame. And so on.

He asked God to forgive his hapless would-be executioners, which earned him the name Panteleimon or "all-merciful" or "all-compassionate". Up to that point he had been known only as, um... [checks notes] "the son of Eustorgius of Nicomedia". Or possibly Pantoleon meaning "in all ways like a lion", but that's suspiciously pat.

At that point he desired that it be possible to behead him, and so they did, "and there issued forth blood and a white liquid like milk."

VisitingNaples

The Kingdom of Naples, always eager for relics and a sucker for martyrologies, came to hold a vial of his blood which, every year on his feast day, turns into a mixture of blood and milk. In today's Italy he's still seen as a good source of lottery numbers.

Even the 1917 Catholic Encyclopedia described all of this as "of recent invention" and "valueless".

However... Closer in time to his life, through the 5th century and into the 6th, he was mentioned in various writings and prominent sermons. Justinian I or Justinian the Great, who built the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, rebuilt a shrine to Panteleimon in Nicomedia at some point during his rule from 527 to 565. Behind all the martyrology there seems to have been a real man, a physician converted to Christianity and martyred during Diocletian's rule.

His relics were translated to Constantinople. You would expect that the Italians stole his relics when they sacked that Christian city in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade. However, there are stories of his relics ending up in today's Azerbaijian.

VisitingSaint-Denis

1: See Mark Twain's comments on being shown multiple heads of John the Baptist during his tour of Europe and west Asia. "That skull seems awfully small." "Oh, but this one is from when he was a child."

Panteleimon was considered a patron saint of physicians and midwives. After the Black Death of mid-14th-century Europe, some of his relics were found at Saint-Denis outside Paris, and his head, or at least one of his heads,1 was venerated at Lyon.

The city of Porto in Portugal also claims to have some bits and pieces of his relics.

Shakespeare used Panteleimon's popular image as a caricature of Venetians. The character, who wore trousers rather than knee breeches, became the origin of the style of trousers called pantaloons, later shortened to just pants.

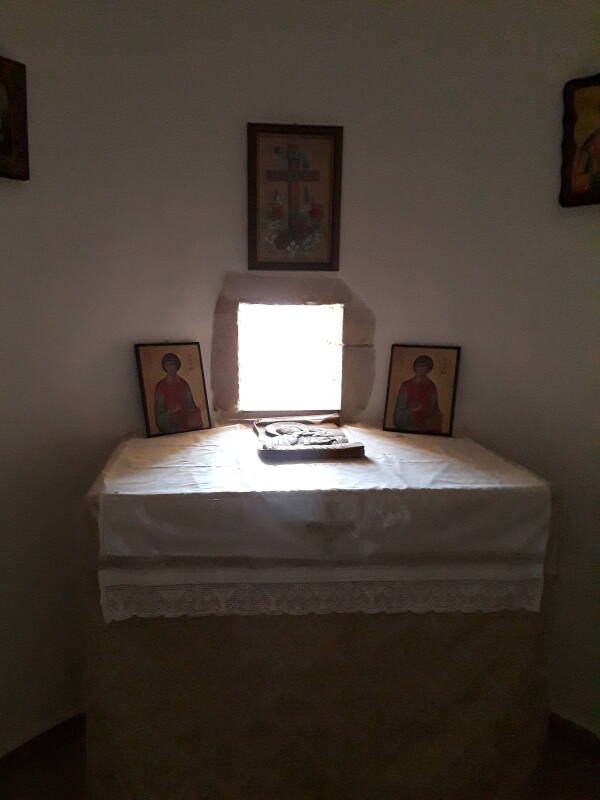

Here's a view of the altar of this small church.

Rizinia Akropolis

Houses, defenses, and lookout points up here date to the Geometric Period toward the end of the Greek Dark Ages, which lasted from about 1100 to 750 BCE.

Following that was the Archaic Period, which lasted up to the second Persion invasion of Greece, so 800 to 480 BCE.

There are two Archaic temples here.

The temples are unusual for blending much older features found in Minoan designs with some features that only became common in Classical Greek architecture of the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.

One of the unusually older features was a single central pillar at the porch, as opposed to two pillars equally spaced between the two sides. That's very Minoan.

The features foreshadowing later developments include friezes in low relief showing a parade of horsemen, and two large goddesses seated above the doorway into the naos or ναός, the inner chamber. Features like that took their full form on the Parthenon in Athens, and haven't been found anywhere else in Crete. Another feature, a frieze with three panthers on each side, is like something out of North Syria.

Snake tubes and goddess figurines with raised arms, as found at Knossos, have been found here. These are real ones, not the modern replicas that Sir Arthur John Evans had his craftsmen create to support his dreams of what Minoan civilization should have been.

These temples were aligned toward the west. That is, as you walk through the outer entrace toward the innermost sanctum, you are walking toward the west.

A square fort toward the west end dates from the later Hellenistic Period of 323–31 BCE.

Necropolis Siderospilia

The Siderospilia Necropolis or Νεκρόπολη Σιδεροσπηλία, the "Iron Cave" burial ground, is about 500 meters northwest, further along the road.

You will notice the two Roman era tombs carved into the rock face right along the side of the road. There were about 680 burials further up the slope above them. The burials go back to the time of the earliest structures on the akropolis. Horses and a few dogs were sacrificed and then bured next to tholos tombs of the 13th to 6th centuries BCE, as described in the ancient literature.

Continue about another hundred meters along the road to the next turn, there's a pull-off area there. These two tombs are at 35.171494° N, 24.998899° E

Let's explore! Here is the left-hand tomb.

There is a burial niche to the left, a cyst tomb in the floor, and a niche in the rear.

Actually two cyst tombs in the floor in front of the rear niche.

And a spacious niche to the right.

Here's a little more detail of the left niche.

Now to explore the right-hand tomb.

The left and center niches:

And the right niche:

Or, Continue Through Greece:

Where next?