Gortyna

Gortyna / Γόρτυνα

Gortyna or

Γόρτυνα

was once the most prominent city in Crete,

and it became the capital of a Roman province spanning

all of Crete plus the Cyrenaica region of coastal Libya.

The hill overlooking Gortyna was occupied back in the

Neolithic age, at least as early as 7000 BCE.

Nearby Phaistos ruled the area during the Minoan age

that ended with the collapse of so many civilizations in

the early 12th century BCE.

Then Gortyn rose to power.

Homer was impressed by it when he described the city

and its defenses around 800 BCE in the Iliad.

It's a large and interesting site along both sides of

the highway near the village of Agia Deka, east of Moires.

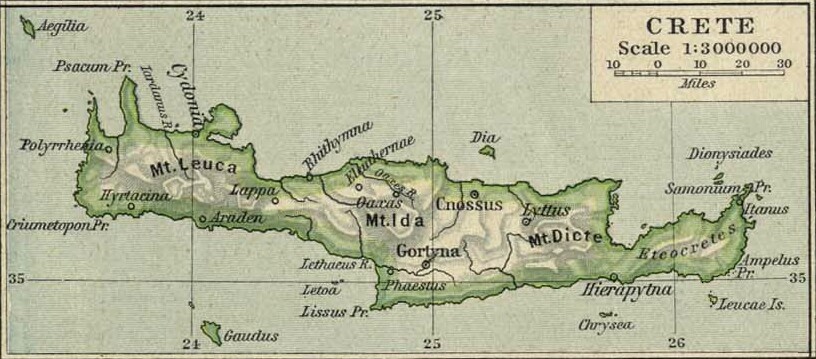

1926 map of Ancient Greece from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. "Hey, you know what would be a great way to write Greek words within English text? Write them in Latin with weird ligatures like 'Æ', the way the Romans did! Then anyone who has studied how the Romans wrote and pronounced Greek would be comfortable!" For those of us who didn't go to an English boys' boarding school with the associated rum, sodomy, and the lash, the pointless Latin spelling is silly and a bother.

The new highway coming south from Heraklion arrives to the west, between Gortyna and Moires. The old road that runs more straight south from Agia Varvara through Ano Moulia arrives to the east, at Agia Deka. The Minoan sites of Phaistos and Agia Triada are to the west, much closer to the coast.

You can see the topography in this map. Gortyn is at that T intersection east of Moiras, shown here as Moírai. Gortyn is on the north edge of the Messara plain, a broad valley with rich agricultural land. Gortyn is where the land starts to slope up to the Psilotiris massif including Mount Ida, the highest point in Crete at 2,456 meters or 8,058 feet.

Tactical Pilotage Chart G-3D from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

It's a nice map, but it was last revised in 1996. It only shows the old road running south from Heraklion.

The Roads company makes excellent maps of Greece. Buy a current map at a service station. Θα ήθελα έναν χάρτη, παρακαλώ — I would like a map, please.

Arriving at Gortyna

As you enter the part of the site north of the highway you pass the Basilica of Saint Titos. That's Τίτος or Titos, an early church leader. He traveled with the Apostle Paul, but he was from Gortyna and tradition says that he died and was buried here.

An ancient olive tree looks as though it might date from the time when Gortyna was prosperous.

There was a settlement on the hill overlooking Gortyn back in the Neolithic age. The hilltop was occupied on into the early Bronze Age. Then during the 7th century CE, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius had the acropolis fortified to provide a shelter for the citizens of Gortyna. Very little of any of that remains.

There was a theatre at the base of the hill. You can see a current archaeological excavation in the distance here, exploring the theatre's remains.

The Gortyna Law Code

An odeon was a building used for musical activities. An odeon is basically a small theatre.

The Odeon of Gortyn was built in the 1st century BCE. Then it was restored by Trajan after being damaged by an earthquake in the early 2nd century CE. Later it was largely destroyed. The brick structure with a large arched opening at its end and four lower arches along its side is a 20th-century reconstruction.

The Odeon's off and on existence and the modern reconstruction of a small section of it leads to the complicated story of the Gortyna Law Code.

Law Codeof Gortyn at

anemi.lib.uoc.gr

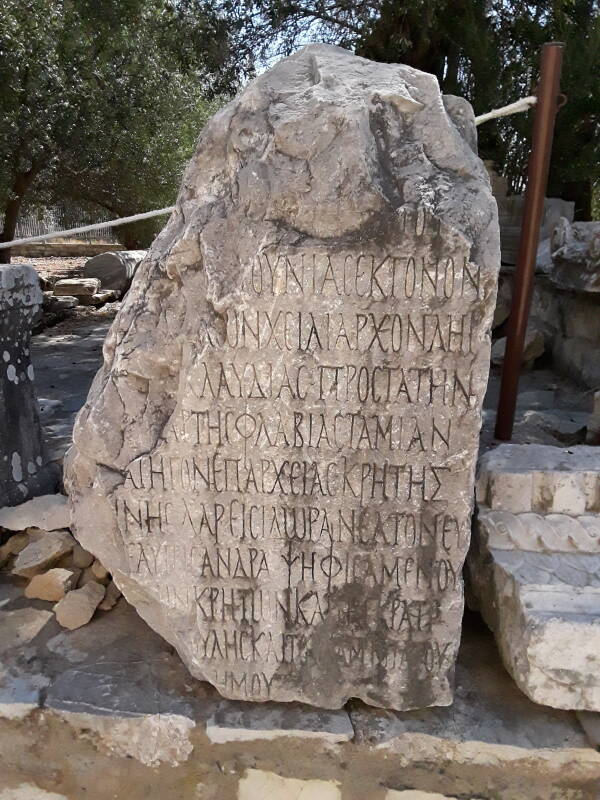

This code contained the laws of Gortyna. It was carved into stone panels during the early 5th century BCE. It's the second-longest existing ancient Greek inscription, and it's by far the largest ancient Greek law code we have. It's the only significant ancient Greek law code known outside of Athens. The inscribed stone panels were built into a circular ekklesiasterion or εκκλησικστήριον. That was the meeting hall for the popular assembly in a city-state of ancient Greece. The people could view and consult the law code.

The 5th century BCE ekklesiasterion was eventually disassembled and its stones were used to build other buildings. The majority of the panels of the code were incorporated into the odeon when it was built in the 1st century BCE.

A fragment of the code was first discovered by two French archaeologists in 1857. The rest of what we have was discovered in 1884 by the Italian epigrapher and archaeologist Federico Halbherr. The new brick structure was built to protect the reassembled code.

The code was written in the Doric dialect of Greek. What we have today is 12 columns, making for a total of 640 lines. It's written in boustrophedron form, "how an ox plows a field", lines in alternating directions. Left-to-right then right-to-left, repeating down the panel.

Of course the western European archaeologists absconded with the panels as they uncovered them. But in recent years most of the inscription has been returned to its home at Gortyn. Two blocks remain in the Louvre in Paris, where they have been since 1868. Convincing replicas take their place here.

The panels show signs of revisions as the laws were changed. And so they provide a view of life in Ancient Greece and how that was changing.

The code shows that the society had classes of widely varying protections and rights and obligations — citizens above serfs who were above slaves. Foreigners were their own category. Only one witness was needed to convict a slave, but five were required to convict a citizen.

As for how the law evolved, slaves gained increasing rights while women, even of the higher classes, lost rights over the years.

Myth says that Zeus took the form of a bull, abducted Europa from Phoenicia, and brought her here and seduced her. This led to the triplets Minos, Rhadamanthys, and Sarpedon, who went on to rule the three major Minoan cities of Knossos, Phaistos, and Malia, respectively.

A myth about that myth says that a plane tree which had to witness the seduction had ever since refused to shed its leaves out of modesty. The 4th century BCE botanist and philosopher Theophrastus believed the whole story.

However, there is a rare species of plane trees in Crete that don't shed their leaves.

Titos and the Early Church at Gortyna

On my way out of the northern section of the site I visited the Basilica of Saint Titos. Little more than its central apse, floor, and wall and column bases remain. It was heavily damaged in an earthquake in 670 and it was abandoned. Then it was largely disassembled and used as a source of building material.

to Titus

The basilica was built in the 6th century under the rule of the Byzantine Emperors. This three-apse church was the largest of its type in Crete.

Tradition says that Titos was buried here after dying at Gortyn in either 96 or 107 CE.

There had been an earlier church at Gortyn, the Great Basilica, also dedicated to Agios Titos. Remains of it, a colorful mosaic floor depicting flowers and birds, were discovered in 1978 about 300 meters to the south at the edge of Mitropolis village.

Titos seems to have been a Cretan Gentile, a non-Jew, who had studied Greek philosophy and poetry. The Apostle Paul convinced him to become a Christian. Titos then served as Paul's scribe, interpreter, troubleshooter, and traveling companion. He accompanied Paul to a council in Jerusalem in 49 CE.

VisitingEphesus

Paul was leaving Asia Minor at the end of the year 56, and sent Titos from where they were in Ephesus to Corinth to deal with the aftermath of Paul's first letter to the Christian community there.

Titos's visit to Corinth was successful, and he traveled north to meet Paul in Macedonia. Paul was delighted with Titos's results, wrote his second letter to the Corinthians, and sent Titos back south to deliver it. Paul later joined Titos in Corinth.

Church tradition plus a passage in Paul's letter to Titos say that Paul visited Crete to preach, and then left after ordaining Titos as the bishop of Crete.

Byzantine era Gortyna had at least six basilicas and smaller churches.

The Church of Agios Titos is one of the most prominent churches in Heraklion, Crete's capital.

There was originally a Byzantine church here, dedicated to Titos. It was destroyed in 1544 in an earthquake followed by a fire.

A church of similar design was built on the ruins in 1557. After the Ottoman Turks seized control, it was converted into a mosque.

That mosque was destroyed by an earthquake in 1856, and a replacement was finished in 1872. That mosque was converted to a church in 1925. It clearly retains the Ottoman mosque design.

Paul's letter to Titos contains a logical paradox called the Epimenides paradox after the Cretan philosopher Epimenides of Knossos of the 6th century BCE. What does it really mean if a Cretan says "All Cretans are liars"? Bertrand Russell presented Epimenides's form of the paradox and went on to pose the related set-theoretic paradox now known as Russell's Paradox. The paradox appeared in Paul's letter as:

One of Crete's own prophets has said it: "Cretans are always liars, evil brutes, lazy gluttons." This saying is true. Therefore rebuke them sharply, so that they will be sound in the faith.

— Titus 1:12-13 (NIV)

The narthex or entry area of the Church of Agios Titos contains a large icon of Titos and a reliquary.

The Venetians seized Titos's head after the 1544 fire, along with Saint Saba's tibia and Saint Ephraim's arm, and enshrined them in Saint Mark's Basilica in Venice.

Titos's head was returned to Greece in 1966 and is now in this reliquary in the Heraklion church dedicated to him. The other relics are still in Venice.

Archaeologists were working around the large temple at the base of the Gortyna acropolis hill when I was there.

Gortyn came under the control of Rome, and was made the capital of the Roman Province of Crete and Cyrenaica. That importance and prosperity drove an expansion of the city toward the southeast, across today's highway. Roman-era Gortyna covered about 200 hectares.

Archaeological work is finally underway again, with improved security. Halbherr had excavated a full-sized statue of Apollo and put it on display at the site. Someone stole it in 1991. It was returned in 2007 through a Swiss antique dealer who had come across it in the antiquities trade.

The large stepped altar at right here is in front of the Temple of Pythian Apollo, from center to left. The temple, built in the 7th century BCE, was the holiest sanctuary in Gortyna, and it was known throughout the ancient world.

The temple was built on the site of a Minoan temple, which may have built on an even earlier holy site established before the Minoan civilization arose. This was the sacred center of the settlement from the earliest beginning until Tinos and others began building Christian churches here.

The specific name Pythian Apollo has to do with Apollo's association with his cult center in Delphi, where he was venerated as the slayer of the monstrous serpent Python.

Legends speak of Apollo's origin in Crete, where he took the form of a dolphin to carry Minoan priests to Delphi. He might be identified with a Minoan deity called Paiawon.

Ptolomy Apion was the ruler of the Hellenistic Kingdom of Cyrenaica, a strip along the Mediterranean coast of what today is Libya. He had separated it from the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt. He died in 96 BCE with no heirs, leaving his kingdom to the Roman Republic.

Rome was happy to get the territory, but was already having trouble managing its expanding empire before receiving this new addition. The Roman Senate decided to leave its administration to local rulers.

Within twenty years, civil uprisings by Jewish settlers were destablizing the province. The Roman Senate managed to handle the situation in 74 BCE by sending a relatively low-level official to restore order, the quaestor Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus. A quaestor was the lowest ranking office in the Roman system, the Senate had basically sent an accountant to run the whole province. And it worked, at least for a while.

Within three years Rome decided that maybe they needed even more territory after all. They sent Marcus Antonius Creticus, whose main accomplishment was being the father of a boy who grew up to become the general Marcus Antonius and seduce Cleopatra.

So-called Creticus had been commissioned to rid the Mediterranean Sea of pirates, a task at which he failed spectacularly. He didn't get rid of any pirates, and he plundered the provinces he was supposed to be protecting. Then he attacked Crete, and they sank most of his ships. He died soon after that, in 72-71 BCE in Crete. The Romans called him "Creticus" as a joke because he certainly hadn't conquered Crete, and the name also meant "Man Made Out Of Chalk".

Then in 69 BCE Rome sent Quintus Caecilius Metellus, who was much more capable. Three years later, in 66 BCE, after what was described as a "ferocious" campaign, he took control of all of Crete. The Romans also gave him the added name "Creticus" but in a completely non-mocking way, because Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus had actually conquered Crete.

The island of Crete and the former kingdom of Cyrenaica were combined into the new Roman Province of Crete and Cyrenaica. Gortyna would be its capital.

The Praetorium complex was built to house the Roman governor and the administrative offices of the new province.

A nymphaeum or spring house was built next to the Praetorium, handling the water brought down from the hill to the north through an aqueduct.

Parts of the Praetorium were modified into a monastery. It operated until the Venetians arrived in the early 1200s, announcing that everyone had to speak Italian and worship in Latin, announcements that got very little traction with the local people. But they did manage to shut down this Greek Orthodox monastery.

The Romans, of course, extended the existing baths, building a new complex to the south of the Praetorium.

The Temple of Egyptian Deities is fifty to a hundred meters north of the Temple of Pythian Apollo.

Isis, Serapis, Anubis, and possibly other Egyptian gods were venerated here.

There is a cluster of Minoan tholos tombs a short distance south of Gortyna. Go through the village of Platanos, exiting the village to the west, watching for the yellow-on-brown sign indicating an archaeological site.

These two are the largest in Crete, at least by diameter, although little remains above the current ground level.

The Libyan coast is 320 kilometers away in a straight line, and the two-part province was difficult to administer. Emperor Diocletian split the province in 298 CE during his process of reorganizing the empire's many provinces. Gortyna remained the capital of the new Province of Crete.

By the time the Saracens invaded Crete around 823–828, Gortyna had already mostly dwindled away.

Next❯ Rizinia and the Siderospilia Necropolis

Or, Continue Through Greece:

Where next?