Adamantas / Αδάμαντας

Adamantas, the Port of Milos

I was traveling through the Cycladic islands in the

central Aegean sea by ferry.

I had been on

Ios

and

Folegandros,

and had just arrived on Milos.

I would stay in the port town of

Adamantas,

also called Adamas,

for a few days while exploring it and a few other towns.

Adamantas is the commercial center of Milos, as it's the port.

Plaka, on a peak well above Adamantas, is the administrative

center.

Starting the Day

There was a nice bakery and coffee shop and small grocery just a block east of where I was staying at the Semiramis Hotel. I got breakfast there every day.

A double Greek coffee and κουλούρι or koulouri, a sesame bread ring.

Actually, this is a πολύσπορο κουλούρι, a multi-grain koulouri. Πολύ – σπόρο. Many grains.

At the Caldera

Milos is a volcanic island, and its large harbor is a flooded caldera about 7 by 4 kilometers in size and up to 130 meters deep.

The volcano is dormant, last erupting around 90,000 years ago during the Pleistocene, but several sulfurous hot springs are still active.

The Lákkos hot spring is across the street from the port. Hippocrates wrote about this spring, saying that bathing in its warm sulfurous water had medical benefits. He wrote that patients traveled from as far away as Athens to cure dermatological conditions.

Tuff

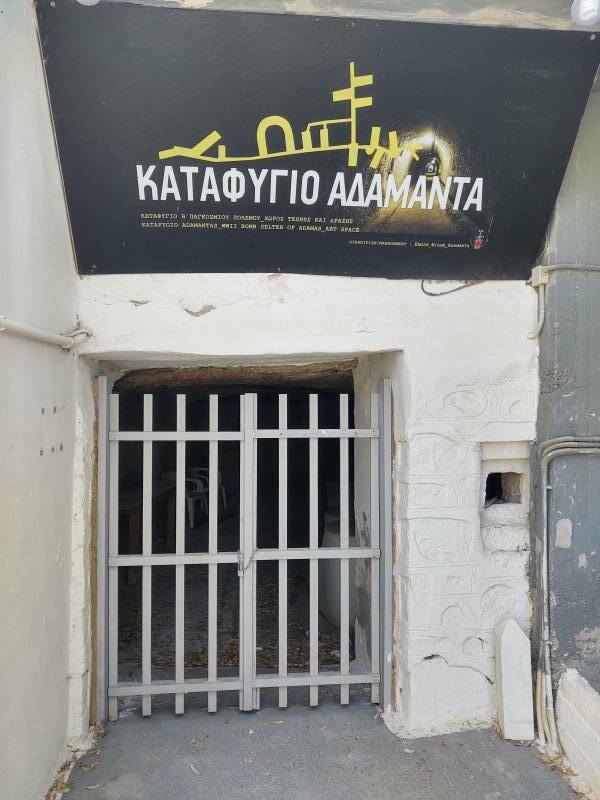

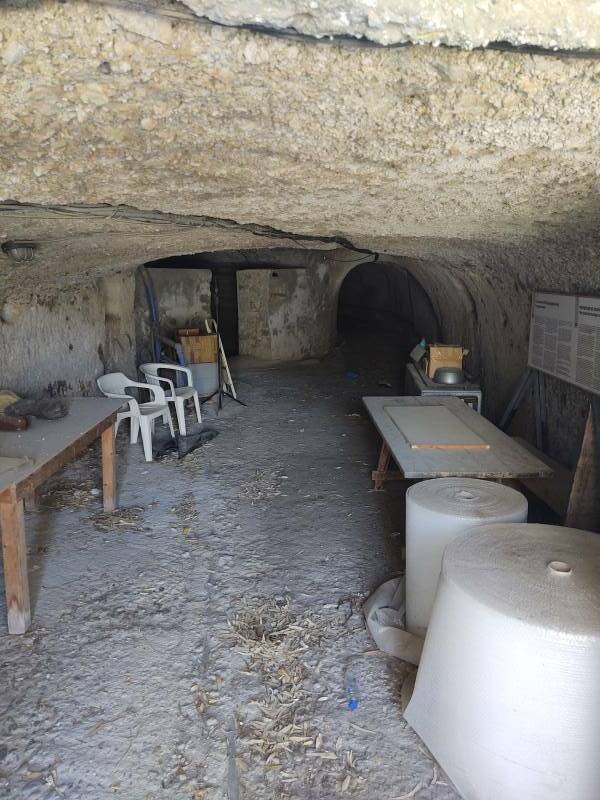

There are thick layers of tuff, compressed volcanic ash that is easy to dig. The local people have dug storage cellars and extensions to their homes. Rooms dug into the tuff are warm in winter and cool in summer.

During the German occupation of World War II, the Germans dug bunkers for shelter from Allied bombing. One of them has recently been reopened and used for art events.

Obsidian

People made the 120-kilometer crossing from the mainland to Milos as early as 15,000 years ago to collect obsidian. That glass, produced by the volcano, can be used to make extremely sharp tools.

I found a small deposit of obsidian beside the gravel road along the shoreline west from the port.

The obsidian collectors originally just visited the island to collect the valuable material. They didn't settle on Milos until the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE. So, over 10,000 years of visiting the island to collect obsidian.

Obsidian is a glass, so it's an amorphous or non-crystalline solid. It undergoes what's called conchoidal fracture, with sharp edges and smooth, curved surfaces.

Here is some of the obsidian I brought back. It's sharp. I chipped off that small flake within a few minutes. Then I noticed that I was bleeding.

Later, settlements were established. There was a strong Minoan influence, a plate engraved with Linear A has been found.

Around 1400 BCE when the Mycenaeans were coming into power, they built a typical Mycenaean-style palace on Milos. It had many rooms and a two-room sanctuary. Workshops produced sculpture and ceramic art.

But then around 1200 BCE most of the great civilizations around the eastern Mediterranean collapsed. The settlement on Milos was abandoned until Dorian settlers from Laconia on the Peloponnese peninsula settled on the island some time in the first millennium BCE. They built their settlement in the area of today's Plaka, Trypiti, and Klima.

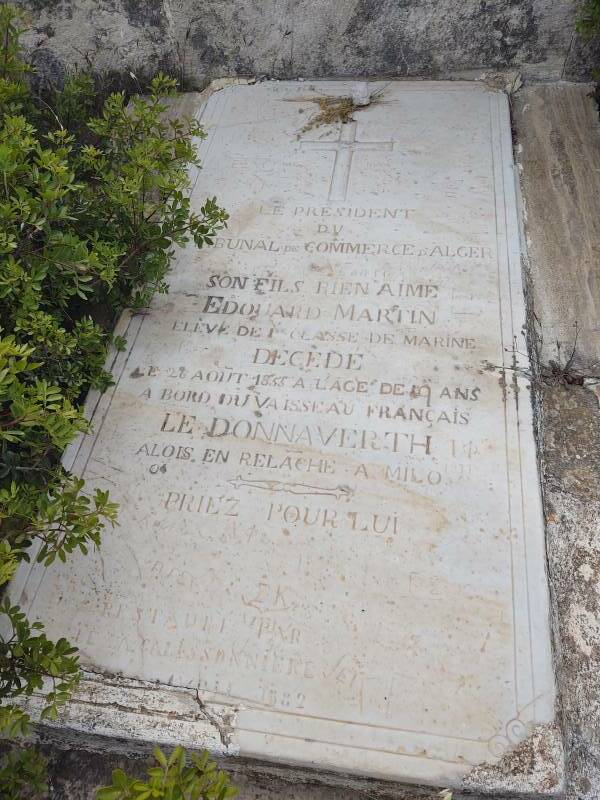

The French Cemetery

As you continue along that rough road toward the lighthouse, you come to a French military cemetery.

French soldiers and sailors from the Crimean War and World War I are buried here. The Crimean War, fought from October 1853 to February 1856, was in the period when the majority of casualties and deaths in warfare were due to disease. The number of deaths by disease exceeded the sum of "killed in action" and "died of wounds" in that war.

Florence Nightingale was acclaimed world-wide for her pioneering advances in modern nursing. She set up a hospital at Constantinople, today's İstanbul, where she and the nurses she had trained cared for wounded soldiers.

The French Crimean War veterans buried here had died of disease or wounds while being transported back to France.

The British and French fleets in the eastern Mediterranean during World War I were based at Milos.

The Deadly Vipers of Milos

In reading about Milos, I came across a warning that you are not allowed to drive rental cars into much of the countryside because of bad roads and the prevalence of the highly poisonous Milos viper. I didn't want to have a car, so I didn't pay much attention to that warning but it did stick with me.

Guesthouses at Booking.comWhen I checked in at my hotel, the manager enthusiastically described the half-day and all-day boat trips you can take out of Adamantas along the western and southern coast. He used a large map of the island to explain the choices.

Then he started telling me about car rentals. He had two lines on the map, one blocking off the western third or more of the island, everything from the narrowest part of the isthmus west. The other blocked off the southeastern 20% or so of the island.

He told me not to even think about driving to those areas, they were strictly forbidden by the car rental companies.

I said that I had read something about bad roads and snakes denying a large fraction of Milos to rental cars.

He sucked air through his teeth while shaking his head, and said, "Yes, snakes. The snakes are very bad."

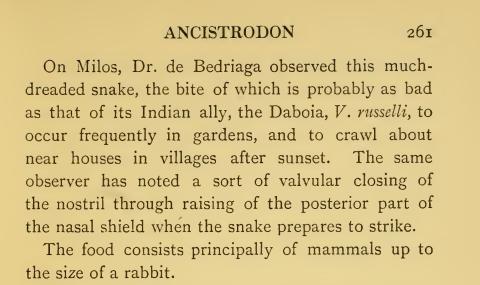

The 1913 volume The Snakes of Europe, which describes itself as the first book in English on the topic, describes a sighting of a Milos viper or Macrovipera schweizeri by a famous Russian herpetologist of the time who operated under a curiously non-Russian name:

The Milos viper is found only on Milos, Kimonos, and Poliaigos; it's now understood that the similar snake on Sifnos is a distinct species. The Milos viper is classified as Endangered and strictly protected under the Bern Convention.

Most Milos viper bites can be treated with no lasting effects, but it's possible for a viper bite to deliver enough venom to kill an adult human.

At this point you might be imagining a rental car being swarmed by snakes which are trying to get into the passenger cabin through the air vents. Or imagining a driver stopping a car, opening the door, and getting out, only to have snakes dropping out of the trees and springing out of bushes to administer their deadly venon. That's fun speculation, but:

The real reason for the ban is to keep cars off the roads in the areas where the remaining snakes live.

The snakes seem to be kind of dumb and slow. There are only about 3,000 of them left in the wild, and many are killed every year by being run over by cars. Milos has put some snake tunnels under some roads, but the snakes prefer crossing the road, stopping to sun themselves in the middle, and not noticing an approaching vehicle until it's too late.

I prefer to think of the Milos viper as an overwhelming deadly scourge of the rugged western area of Milos. The terrifying shrieking eels of Milos who strike fear into the hearts of both residents and visitors.

Around Adamantas

Fishing boats set up a small market along the road on the east side of Adamantas.

Museum

There's a mining and mineral museum near there, with interesting displays on the many commercial minerals found on Milos. Baryte, sulfur, alum,2 and gypsum used to be mined here. Pliny wrote that Milos was the most abundant source of sulfur in the ancient world, and the alum of Milos was second only to that of Egypt.

2: Natural alum deposits played a large role in the birth of the English chemical industry.

The museum also had an interesting exhibit on obsidian, verifying for me that what I had picked up along the road near the port was the volcanic glass and not flint.

Today bentonite, perlite, pozzolana, and kaolin are dug out of open-pit mines.

EcclesiasticalMuseum

The Naos Agia Triada or the Church of the Holy Trinity is also the home of the Ecclesiastical Museum. The church dates from the 13th or 14th century.

Or, Continue Through Greece: