Trypiti / Τρυπητή

Trypiti and its Catacombs

Τρυπητή

or Trypiti is best known for the nearby

catacombs, Hellenistic statues including

the Aphrodite of Milos,

called the Venus de Milo

by the French who absconded with it,

and the later Roman-era developments including a theater.

The name Trypiti, which means something like "made with holes",

comes from the fact that the settlement is built on

tuff,

easily carved rock formed from compressed volcanic ash.

The local people started excavating a large network of

catacombs in the 1st century CE and continued enlarging

it into the 7th century.

They're considered one of the most important early Christian

monuments in Greece, and are second in size only to those in

Rome and Jerusalem.

The inhabitants of Milos still carve storage areas and even

well-insulated underground rooms for their homes.

The bus from Adamantas goes through Pera Triovasalos and Plaka on the way to Trypiti, and then returns in the reverse order. The bus stops near Trypiti where a road leads down to the catacombs. It's not a problem if you miss the catacomb stop and go all the way to the bus lot in Trypiti, as it's a short walk back. When I was there in early May, the bus left Adamantas at 0730, 0830, 1030, 1230, 1500, 1630, and 1830; and left Trypiti at 0630, 0750, 0950, 1150, 1350, 1550, and 1750.

The side road to the catacombs is about half a kilometer long, winding sharply as you descend about 70 meters from the Plaka–Trypiti road.

That's the waterfront settlement of Κλήμα or Klima ahead of us. Part of the way down, with a glass roof over some now exposed tombs, is the entrance to the catacombs.

There's a chapel on a small volcanic outcropping. It overlooks the Roman theater. The site where the Αφροδίτε της Μήλου or the Aphrodite of Milos was found is near that. A path from the road to the catacombs leads to the discovery site and theatre. France renamed the statue Venus de Milo.

France had a vast collection of antiquities after all the looting done by Napoleon's forces. But then after he fell from power, France began returning some of the pieces. Laocoon and his Sons and the Venus de Medici, two of the Louvre's most striking pieces and considered two of the finest classical statues, went back to Italy in 1815 and 1816.

A local farmer looking for cut stones for his construction project discovered the Aphrodite of Milos in 1820. A French naval officer found out about about the discovery. Louis Brest, the French consul in Milos in 1820, managed to seize control of it. Charles-François de Riffardeau, the Marquis de Rivière, French ambassador to the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire, arranged for its purchase.

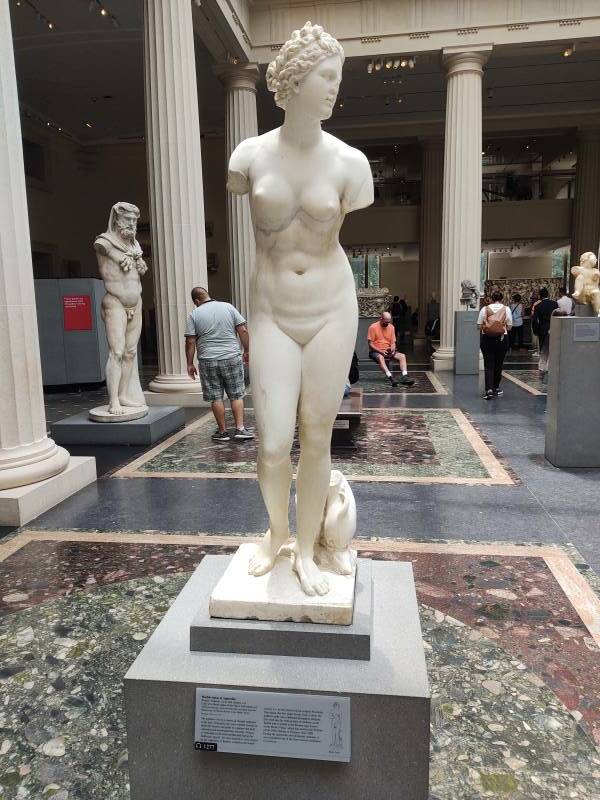

Anachronistically renamed the Venus de Milo, it was prominently placed in the Louvre in 1821 and then promoted by France through the rest of the 19th century as a greater treasure than what they had recently returned. Many artists and critics fell in line praising it as the ultimate example of graceful female beauty, created by the 4th century BCE Athenian sculptor Praxiteles.

Some scholars today say that it probably represents the sea-goddess Amphitrite, who was worshiped on Milos.

As discovered, it included a plinth with an inscription indicating that it was made later, in the Hellenistic period, by Alexandros of Antioch.

And so, a coverup. The French hid the plinth and promoted the statue as depicting the more prominent goddess Aphrodite, made by the respected Praxiteles during the much more auspicious Classical period. Eventually the inconvenient plinth disappeared. Only two drawings and an early description survive.

Not all of France followed the official party line. Pierre-Auguste Renoir described it as "a big gendarme".

Praxiteles was the respected master. He created a statue of Aphrodite in the 4th century BCE. It was installed in a sacred precinct at ancient Knidos in southwestern Asia Minor. It caused an immediate sensation, and inspired many re-creations through the following centuries.

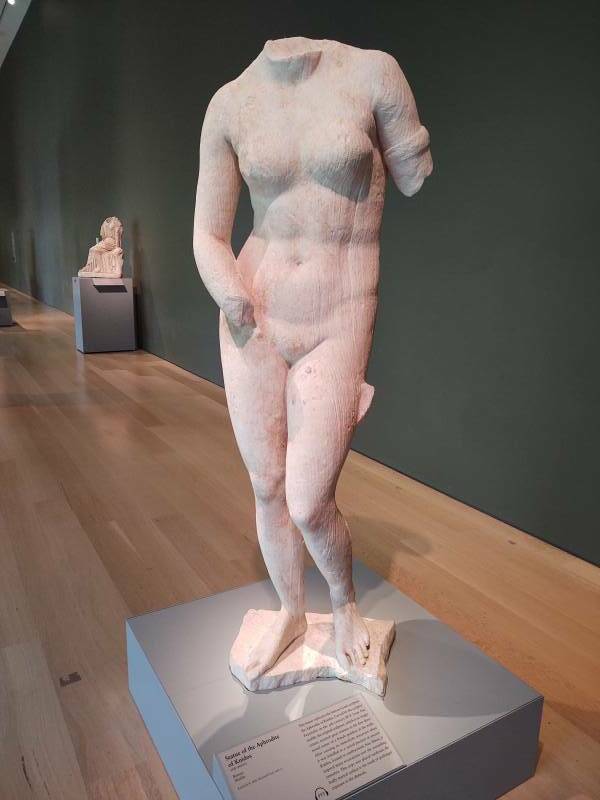

This statue at the Art Institute of Chicago is a Roman copy from the 2nd century CE. Left out in the weather for a prolonged time, its marble surface became badly scarred.

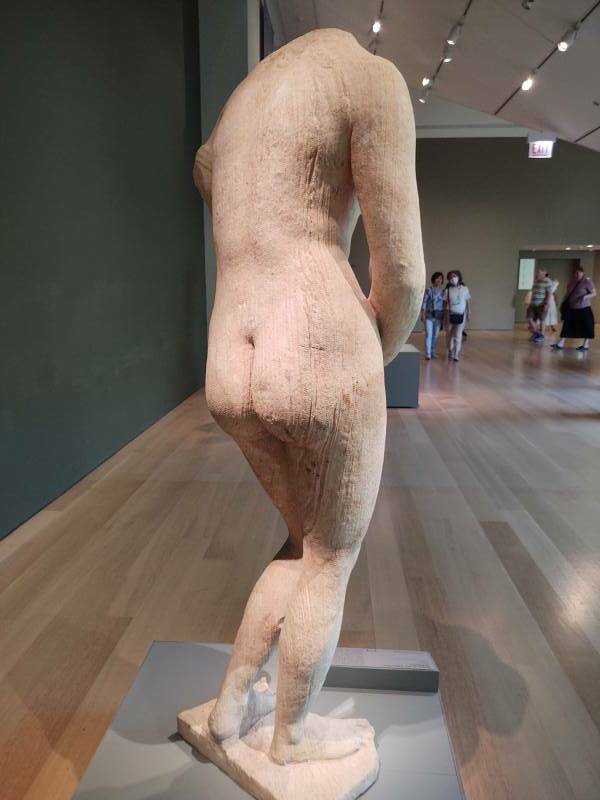

This statue at the Metropolitan Museum in New York is another Roman copy of Praxiteles' work. This one is from the 1st or 2nd century CE.

Continuing on down the slope I approached the catacombs:

I arrived. There are some displays showing how the catacombs are dug back into the face of the slope, and how the individual graves are arranged.

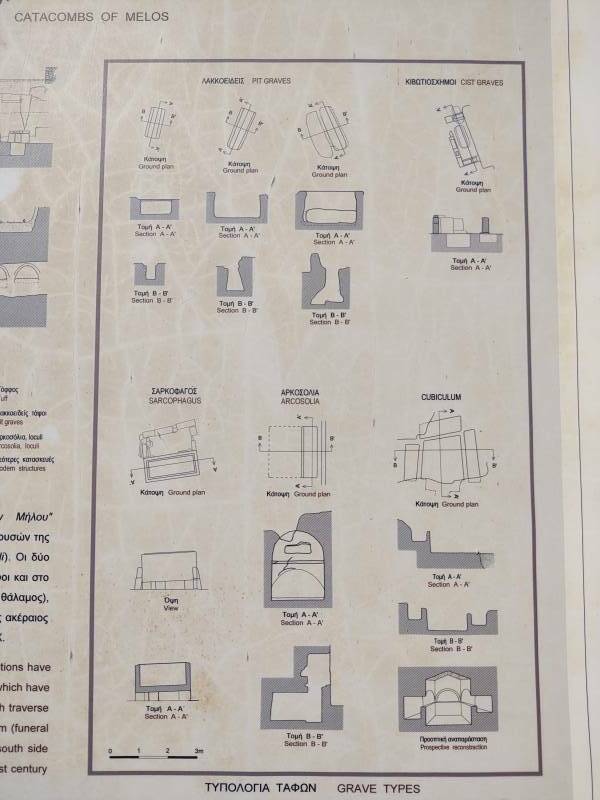

The total length of the catacomb corridors is about 200 meters. The corridors are 1–5 meters wide and 1.6–2.5 meters high.

Some of the tombs are carved into the walls of the corridors. The original investigators applied Latin names, the cubiculum being rectangular graves carved into the wall, and the arcosolia or loculi having arches. There are also rectangular cist or pit graves dug into the floor.

Local people rediscovered the catacombs during the centuries of Ottoman rule, and the looting began.

They were publicly announced in 1840, and the German archaeologists Ludwig Ross and Anton Prokes von Austen visited them in 1843. Ross estimated that the catacombs contained 1,500 to 2,000 tombs where 7,000 to 8,000 people had been buried. Then the French archaeologist Charles Bayer visited in 1879.

Greek archaeologists got involved in the early 20th century. Georgios Lampakis in 1904 may have been the first to do systematic excavations as opposed to just observing and measuring. Then Georgios Sotiriou did a systematic analysis in 1927. He found that many of the slabs covering graves as observed by Ross in 1843 were now missing.

Further excavations were carried out in the 1950s and 1960s. A recent investigation in 2007 through 2009 showed, among other discoveries, that the catacombs had been used into the 6th or 7th century, instead of being abandoned in the 4th century as previously thought. A series of severe earthquakes and raids in the 7th century largely ended the settlement and its use of the catacombs.

You have to visit with a guide, and the length of your visit is limited. This limits the damage to remaining pigments caused by humidity from the breath of visitors.

Some of the arcosolia have niches in their arched drums where lamps or votive gifts could be placed. Other arcosolia niches were used for infant burials.

Some of the arcosolia retain some of their color decoration and fragments of inscriptions. The earliest scientific investigators observed that the drums were painted blue with red rims.

Many of the inscriptions described by the early investigators can no longer be seen. They were done in red, typically listing Greek names and sometimes mentioning ecclesiastical titles. Some had a Christogram ☧ while others had Α Ω, Alpha and Omega. The Christian symbol ΙΧΘΥΣ also appeared.

Fired clay lamps were found throughout the catacombs, at least one was marked with Jewish symbols. Few of the graves still held any objects left as offerings or votive gifts. The looters had been pretty thorough. The archaeologists found a few amulets, a ring, some glass censers, and glass beads.

They also found some kitchen utensils, wine glasses, and bones of animals and fish, showing that funeral dinners and other rituals in memory of the dead took place in the catacombs. Some of the vessels had been imported from Asia Minor, Cyprus, and North Africa.

The catacombs have one elevated tomb in the form of a sarcophagus. It seems to have once been covered by a wooden coffin. It probably belonged to one of the first Christian bishops of Milos. It was used as an altar for religious services, a practice that continued off and on to recent years.

Tunnels connect the branches of the catacomb corridors.

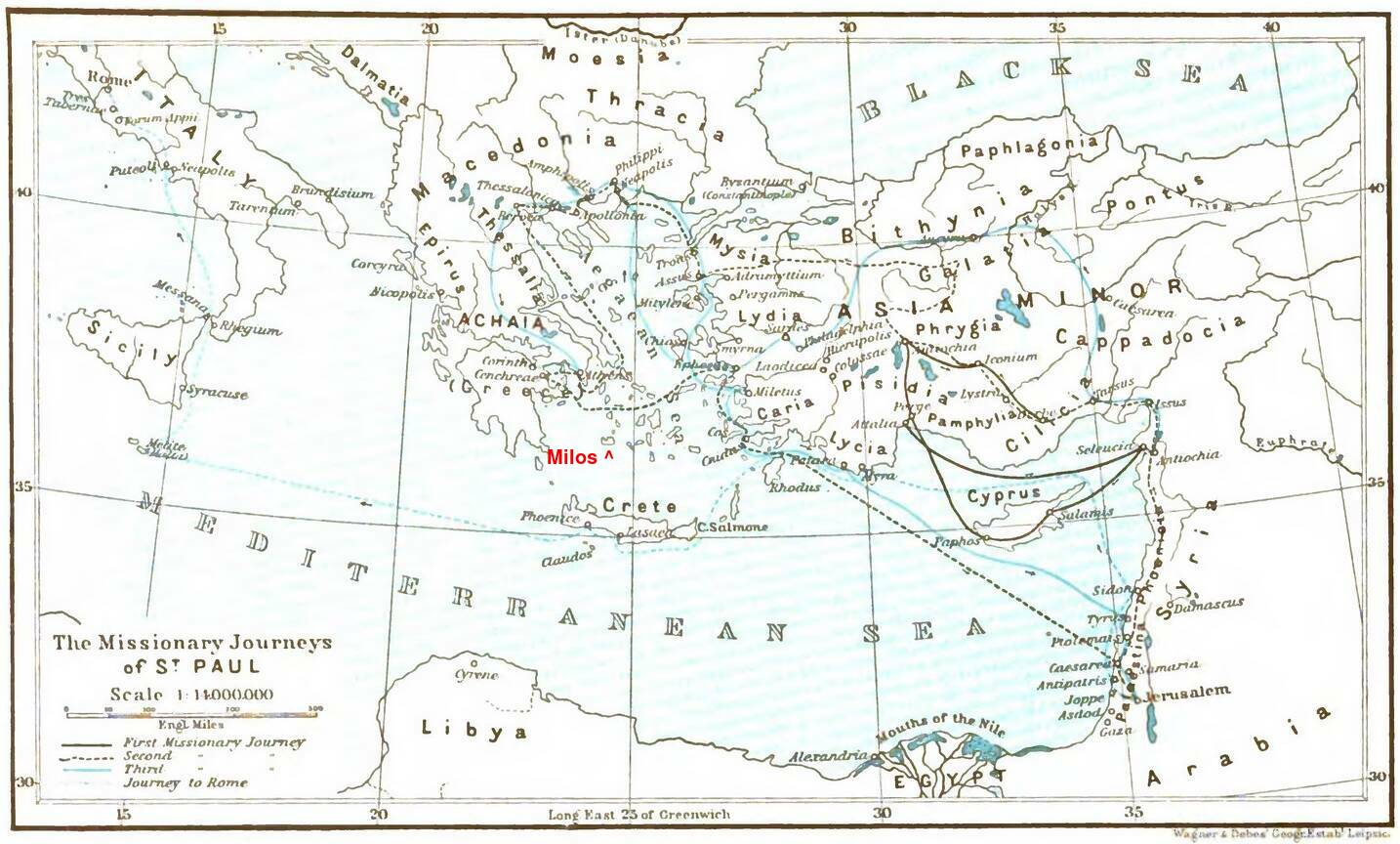

Much of the limited online material about the catacombs talks about Paul visiting Milos. Much of it seems to be the same content copied from one web page to another. It just doesn't align with what we know about his travels. As described in Acts of the Apostles, Paul went on three missionary journeys around Asia Minor and Greece, and then a trip from Jerusalem to Rome.

Much of the doubtful speculation on Paul's supposed visit to Milos says that he was shipwrecked here while on his way from Athens to Crete. But we know nothing about such a voyage. The shipwreck described in Acts of the Apostles is clearly on Malta after some rough sailing along the southern coast of Crete.

He might have stopped on Milos on his way from Corinth to Ephesus while on his way back to Jerusalem on his second missionary trip.

Other online material emphasizes how the early Christian population on Milos would have been predominantly Jewish.

Jews may have fled from Palestine to Milos after a series of persecutions of the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, and some of them may have been early Christians. However, the names in the inscriptions in the catacombs are predominantly Greek.

The catacombs are interesting and impressive. And they clearly demonstrate an early Christian community on Milos. But if the apostle Paul was somehow personally involved here, we have no evidence for it.

Trypiti

I walked back up to the Plaka–Trypiti road and continued into Trypiti. It's a small town with about 400 residents.

The large Church of Saint Nicholas dominates the town.

Lunch in Pera Triovasalos

I had noticed a taverna next to the bus stop in Pera Triovasalos. It was a walk of about a kilometer to get there.

I could get lunch right at the bus stop for my return to Adamantas.

I had a great χωριάτικη σαλάτα or traditional salad.

Or, Continue Through Greece: